Coercive Control Literature Review

Final report

June 2023

Stephanie Beckwith, Lauren Lowe, Liz Wall, Emily Stevens, Rachel Carson, Rae Kaspiew, Jasmine B. MacDonald, Jade McEwen, Melissa Willoughby, Luke Gahan

Download Research report

Overview

This report presents a literature review on coercive control in the context of domestic and family violence, with a particular focus on the understanding of, and responses to coercive control in the Australian context. Commissioned by the Australian Attorney-General’s Department, this review focuses on identifying, summarising, analysing and synthesising the existing Australian academic research and evaluations on coercive control. The review highlights the complexities of defining, recognising, and responding to coercive control and identifies relevant gaps in the evidence base.

Drawing from a range of quantitative and qualitative studies across scholarly and grey literature, including non-government reports, government and parliamentary reports, peak body reports, and position papers, this review captures the growing recognition of coercively controlling behaviour in the context of family and domestic violence.

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Cisgender | Cisgender “describes a person whose gender identity aligns with the sex that was assigned to them at birth” (Our Watch, ANROWS & VicHealth, 2015, p. 133). |

| Cisnormativity | Cisnormativity is defined as a “general perspective that sees cisgender experiences as the only, or central, view of the world. This includes the assumption that all people fall into one of two distinct and complementary genders (man or woman) which corresponds to their sex assigned at birth (male or female) or what is called the gender binary. It also relates to the systemic and structural privileging of the social models of binary sex and gender” (Our Watch, ANROWS & VicHealth, 2015, p. 133). |

| Coercive control | “While there is no single agreed definition of coercive control, research indicates that it generally involves conduct that is intended to dominate and control another person, usually an intimate partner, but may also occur in the context of familial or carer relationships (Carson et al., [AIFS], 2022, p. 9, citing ANROWS, 2021). Coercive control is regarded as being perpetrated predominantly by men against women and may include threats to harm; physical, sexual, verbal and/or emotional abuse; psychologically controlling acts; financial abuse; social isolation; systems abuse (defined below); stalking; deprivation of liberty; intimidation; technology-facilitated abuse; and harassment” (Carson et al., [AIFS], 2022, p. 9, citing ANROWS, 2021). |

| Domestic and family violence | Domestic violence is defined as “acts of violence that occur in domestic settings between two people who are, or were, in an intimate relationship. It includes physical, sexual, emotional, psychological and financial abuse” (Our Watch, ANROWS & VicHealth, 2015, p. 133, citing Morgan & Chadwick, 2009). Family violence refers to violence occurring in a broader familial context (for example, elder abuse), as well as violence within intimate partner contexts (Our Watch, ANROWS & VicHealth, 2015). In a family law context “under the Family Law Act (FLA) 1975, family violence refers to violent, threatening or other behaviour that coerces or controls a family member (including relatives, de facto partners and spouses) or causes them to be fearful: FLA s 4AB(1). Behaviours that may constitute family violence include assault, sexual abuse, stalking, repeated derogatory taunts, intentionally damaging property and financial abuse: FLA [Family Law Act 1975 (Cth)] s 4AB(2)” (Carson et al., [AIFS], 2022, p. 10, citing the Family Law Act, 1975). |

| Economic abuse | Economic abuse is defined as behaviours perpetrators use that inhibit a victim-survivor’s ability to make decisions, control and maintain economic resources (Singh, 2020). |

| Financial abuse | Financial abuse refers to a perpetrator’s control of money and finances in the household (Singh, 2020). |

| Intersectional(ity) | In the context of coercive control, scholars who take an intersectional approach underscore that the risk factors for experiencing coercive control are shaped by numerous intersecting inequalities, including but not limited to gender, age, race, ability, and geographical location (Our Watch, ANROWS & VicHealth, 2015). |

| Intersex | Intersex people have innate sex characteristics that do not fit medical and social norms for female or male bodies, and that create risks or experiences of stigma, discrimination and harm (Intersex Human Rights Australia, 2013). These characteristics can be physical, hormonal, or genetic, and some intersex traits become apparent at puberty, or when trying to conceive, or through random chance (Victorian State Government, 2019). Intersex people do not share any identity, they are a very diverse population; those old enough to freely express an identity can be heterosexual or not, and cisgender (identify with sex assigned at birth) or not (Intersex Human Rights Australia, 2013). |

| Non-fatal strangulation | Non-fatal strangulation is often perpetrated in the context of coercive control and occurs when a perpetrator strangles a victim-survivor who is not able to breathe due to the force used to compress the neck. This form of abuse does not always result in visible injury but has been identified as a risk factor for intimate partner homicide (Bendlin & Sheridan, 2019). |

| Perpetrator | A person who uses any form of violence against a victim-survivor (Department of Social Services, 2022). |

| Psychological or emotional abuse | Psychological or emotional abuse refers to non-physical abusive behaviours including but not limited to: demeaning, threatening, degrading and intimidating behaviours (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022; McMahon & McGorrery, 2020). |

| Queer | Queer is an umbrella term for diverse genders or sexualities. Some people use queer to describe their own gender and/or sexuality if other terms do not fit (Victorian State Government, 2021). |

| Reproductive coercion | Reproductive coercion can be defined as behaviour that interferes with or prevents a person (usually women) from exercising their autonomy and control in reproductive decision-making (Tarzia et al., 2019). It is usually perpetrated by intimate partners but can also be characterised by perpetration within familial relationships (Tarzia et al., 2019). |

| Sexual violence | The Department of Social Services (2019, p. 60) defines sexual violence as “sexual actions without consent, which may include coercion, physical force, rape, sexual assault with implements, being forced to watch or engage in pornography, enforced prostitution or being made to have sex with other people.” |

| Systems abuse | Systems abuse refers to the exploitation of government and/or legal systems by perpetrators of domestic and family violence and coercive control to exert power and control over victim-survivors (Department of Social Services, 2022). Litigation tactics may be used to “gain an advantage over or to harass, intimidate, discredit or otherwise control the other party” (National Domestic and Family Violence Bench Book, 2021). |

| Technology-facilitated coercive control | Technology-facilitated coercive control is a form of abuse that involves the utilisation of technologies to abuse, control and intimidate victim-survivors (Dragiewicz et al., 2021). Perpetrators of technology-facilitated coercive control can use technologies such as text messaging, social media messages and posts, GPS, and online monitoring to control victim-survivors (Dragiewicz et al., 2021). |

| Victim-survivor | A victim-survivor is a person who has, or is experiencing, domestic and family violence, sexual violence and/or coercive control (Department of Social Services, 2022). |

Executive Summary

This report presents a literature review on coercive control in the context of domestic and family violence, with a particular focus on the understanding of, and responses to coercive control in the Australian context. Commissioned by the Australian Attorney-General’s Department, this review focuses on identifying, summarising, analysing and synthesising the existing Australian academic research and evaluations on coercive control. The review highlights the complexities of defining, recognising, and responding to coercive control and identifies relevant gaps in the evidence base.

Drawing from a range of quantitative and qualitative studies across scholarly and grey literature, including non-government reports, government and parliamentary reports, peak body reports, and position papers, this review captures the growing recognition of coercively controlling behaviour in the context of family and domestic violence.

Definitions of coercive control

Coercive control is a gendered phenomenon that occurs in a broader context of gender inequalities and norms, amongst other intersectional inequalities (ANROWS, 2021; Douglas et al., 2019; Harris & Woodlock, 2019). While there is no single agreed upon definition of coercive control, the literature drawn upon from this review commonly refer to a range of tactics used by (usually male) perpetrators to control or dominate the victim-survivor, including: physical and/or sexual violence, emotional or psychological abuse, stalking and surveillance, social isolation, financial abuse, technology-facilitated abuse, reproductive coercion, and systems abuse (Stark, 2007).

Prevalence of coercive control

This review illustrates that there is currently limited available data on the prevalence of coercive control (rather than domestic and family violence (DFV) more broadly) in Australia. In the absence of a single agreed definition of coercive control, data on prevalence is difficult to capture in a consistent and meaningful way (Bendlin & Sheridan 2019; Boxall et al., 2020; Mayshak et al., 2020). The lack of prevalence data on coercive control is a significant gap identified in this literature review.However, data from a range of surveys based on different samples applying diverse approaches to measuring the constructs provide insight into the nature and experience of coercive control. Findings from the only population level source available do not specifically refer to coercive control. However, 6% of women experienced emotional abuse by a current partner since age the of 15, with just over three-quarters of these participants reporting threatening or degrading behaviours and more than one-third reporting controlling financial behaviours (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022).

Impacts and experiences of coercive control

Coercive control can have a range of diverse impacts on victim-survivors that can be short and/or long term in nature. These include health impacts (physical and mental) including post-traumatic stress disorder (Hegarty et. al., 2013), social isolation, and reduced help-seeking (Boxall et al.,2020). The sense of loss of self (Moulding, 2021) and feelings of entrapment (Pitman, 2017) are commonly reported in qualitative studies and the impact on a victim-survivor’s sense of self-trust and self-belief as a result of coercive and controlling behaviour including gaslighting, are noted as contributing to further abuse (Easteal, 2021). Coercive control is also identified as having a range of significant impacts on children such as negative behavioural outcomes and psychological, and emotional consequences into adulthood (Women’s Safety and Justice Taskforce, 2021). Notably some research literature identifies that the impacts of coercive control may be worse than other forms of family violence (Moulding et al., 2021).

Discussions of coercive control within the literature focus on the multiple and diverse experiences of different groups of people. The groups identified throughout this literature review are by no means an exhaustive list of groups who may be at heightened risk of experiencing coercive control, nor are they mutually exclusive. The discussion reflects the main groups featured throughout the studies, including Culturally and Linguistically Diverse communities, First Nations people, people with disability, people living rurally, children and youth, and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex or Queer (LGBTIQ+) people. The studies included capture a range of experiences which are unique to the identities of some subgroups. They also highlight a shared experience of both non-physical and physical violence and abuse used by perpetrators to diminish the autonomy of the victim-survivor. These findings exemplify the nature of coercive control within these contexts and highlight some unique risk factors for particular groups. For example, evidence suggests that Culturally and Linguistically Diverse groups can be at higher risk of experiencing coercive control, with some victim-survivors being financially dependent on perpetrators and being subject to temporary visa status (Tarzia et al., 2022). There is a consensus that intersectional identities shape risks of coercive control victimisation.

Community awareness of coercive control

Another key finding relates to the lack of community knowledge and awareness of coercive control. For instance, a study by Webster and colleagues (2021) highlights the myths surrounding coercive control shifts blame and responsibility onto the victim-survivor and serves as additional barriers to seeking help. There is acknowledgement across the wide range of literature that in order to better identify and respond to coercive control, awareness and knowledge must be increased throughout communities (Harris & Woodlock, 2019, 2021; Webster et al., 2021; Women’s Safety and Justice Taskforce, 2021), healthcare and response systems (such as the police) (Buchanan & Humphreys, 2020; Harris & Woodlock, 2019; 2021), and legal systems (Wangmann, 2020). Research also shows that community awareness can influence help-seeking behaviour. This influence can be negative resulting from engrained attitudes or fear of backlash (Bendlin & Sheridan, 2019; Harris and Woodlock 2019; Women’s Safety and Justice Taskforce, 2021). It can also be positive, as friends, family, and colleagues can function as an informal support network and can further empower the victim-survivor to seek formal support (Women’s Safety and Justice Taskforce, 2021).

Further, a gap was identified in the literature regarding victim-survivor lived experience advocacy in coercive control response models which, if addressed, will provide important evidence on the strengths and deficiencies of current approaches and frameworks and contribute to improving these moving forward.

Effectiveness of approaches and interventions

The literature review considers the effectiveness of approaches and interventions to address coercive control, finding that the research identifies a need for improved risk assessment frameworks and consistency in defining coercive control and Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) (Douglas 2021a; Johnson et al., 2019). Similarly, discussions on integrated response systems are identified throughout the literature on perpetrator support to mitigate contributing risk factors such as mental health or alcohol or drug services, notably through men’s behaviour change programs (Commonwealth of Australia, 2015). Discussions on the effectiveness of judicial and police response systems highlight the strengths and deficiencies of current approaches in addressing and responding to coercive control. Key findings from this research include the need for greater acknowledgement from justice responses of the severity of harm caused by patterns of coercively controlling behaviours (Parliament of New South Wales, Joint Select Committee on Coercive Control, 2021; Tolmie, 2021). Australian and international resources highlight the need for training specific to coercive control throughout the responding judicial, criminal and health sector systems. In addition to training, integration of these systems would improve responses by ensuring consistent definitions and the ability to recognise non-physical violence as a serious form of IPV and DFV (Douglas, 2021a).

Criminalising coercive control

The debate on criminalising coercive control highlights the complexities and the diverse perspectives both for and against criminalising in Australia. Key arguments in favour of criminalising, highlighted in the review, were the ability to expand evidence beyond physical violence to demonstrate that IPV or DFV has occurred (Our Watch, 2021) as well as to publicly denounce coercive behaviours. Others have called for improvements to existing mechanisms and response systems and including civil laws (Women’s Safety and Justice Taskforce, 2021a; Women’s Legal Service Victoria, 2015). The literature review considers international and domestic jurisdictions where legislation has been implemented to further explore this debate. However, as observed throughout the literature, the criminalisation of coercive control may result in unintended negative consequences, most significantly among First Nations women who face structural inequalities and barriers particularly in the justice system and are likely to be placed at increased risk of being misidentified as perpetrators by police (Parliament of New South Wales, Joint Select Committee on Coercive Control, 2021; Women’s Safety Justice Taskforce, 2021, p. xviii). This can result in reduced trust that victim-survivors will receive the help they need (Parliament of New South Wales, Joint Select Committee on Coercive Control, 2021), and reduce the effectiveness of the legal and health systems to support those most at risk from coercive controlling behaviours.

1. Introduction

The Australian Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) has commissioned the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS), to undertake this review of literature on coercive control in relation to domestic and family violence, with a particular focus on the understanding of, and responses to, coercive control in the Australian context. This literature review identifies, summarises, analyses and synthesises the existing Australian research and evaluations on coercive control issues and interventions, identifying relevant gaps in the evidence base.

As agreed with AGD, this literature review covers the following topics:

- the defining features and important elements of coercive control in the domestic and family violence context

- the experiences of coercive control by perpetrators and victim-survivors (according to demographics, relationship type), including children and young people

- the gendered and other intersectional drivers and reinforcing factors that influence coercive control

- short- and long-term impacts of coercive control on victim-survivors, families and communities (including economic analysis where available)

- community awareness of coercive control, including understanding of the relationship between coercive control and family and domestic violence, and including myths and misconceptions of coercive control

- the experiences of coercive control by particular cohorts (including those affected by discrimination and inequality)

- the role of victim-survivor lived experience and advocacy in addressing coercive control, and

- unintended consequences of criminalising coercive control including misidentifying victim-survivors as perpetrators and the risk of increasing the over-representation of First Nations people in the criminal justice system.

Consideration is also given to:

- the experience of, and access to, legal support and justice for victim-survivors

- the experience of, and access to, support for perpetrators

- the effectiveness of approaches and interventions to address coercive control across prevention, early intervention, response and recovery (including education and awareness initiatives), and

- the effectiveness of the criminal and civil justice efforts to address coercive control.

Further, the literature review:

- applies a national lens that involves consideration of matters relating to states and territories and Australia as a whole, with consideration given to urban, regional, rural and remote locations

- identifies, analyses, and summarises the issues by theme

- identifies areas of disagreement and gaps in the available Australian evidence base, and

- considers position papers and international research as required.

Review methodology

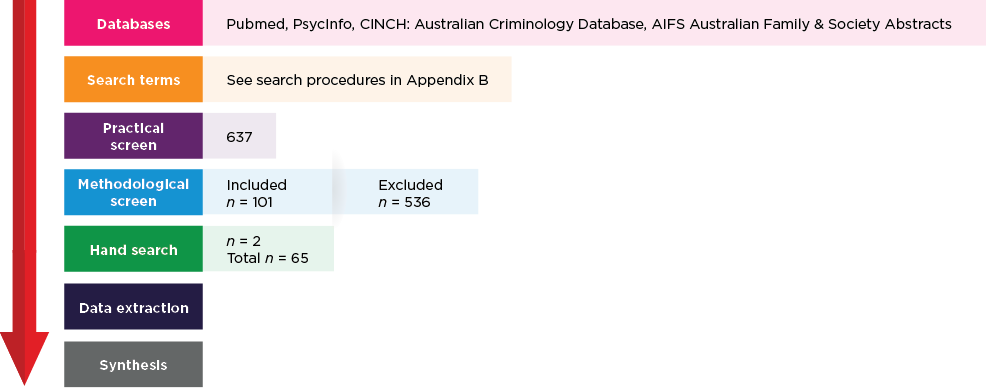

This literature review follows the method outlined by Fink (2010) and is consistent with the World Health Organization rapid review guidelines by King and colleagues (2017). The method has three main elements: (1) sampling the literature; (2) screening the literature and (3) extracting data. Figure 1 shows the steps taken throughout the procedure, beginning with the databases that were searched and concluding with the synthesis of results. This procedure is consistent with the PRISMA checklist for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Moher et al., 2009).

In total, the database searches yielded 689 results, and 52 duplicates were removed.

Two reviewers completed the practical screen for the same 100 articles. The purpose of this being to calibrate, ensuring the inclusion and exclusion criteria were being applied consistently and providing an opportunity to update the criteria based on the kinds of studies identified. After this initial calibration, the remaining articles were split between the two researchers. At this stage, 536 studies were excluded for not meeting the eligibility criteria. A total of 101 studies were then assessed for eligibility by full text by two researchers. A total of 63 studies from these searches were included in the final sample. Hand searches produced further material, with two further sources being included at this stage. All remaining resources included were identified through the researcher’s expertise.

Following consultation with AGD, the research team undertook a series of supplementary searches, representing an addendum to the initial searches described above. The materials that were included on this basis are denoted with an asterisk in the reference list.

Figure 1: Flow chart of the review process

The sample

The literature was sampled in two steps. First, key terms were used to source relevant studies from four electronic databases. The databases that were searched are listed in Figure 1. These databases were chosen because they contain content from disciplines likely to store research and practice literature related to coercive control (psychology, social work, sociology, criminology, and health and nursing). The additional appeal of CINCH: Australian Criminology Database was that it provided relevant Australian government and peak body reports.

The search terms were developed based on:

- the desired topics outlined in the Request for Quotation document provided by the AGD

- previous research activities associated with the coercive control review that is currently being conducted within the AIFS, including stakeholder engagement and a review (see Appendix A for further detail on these activities).

The search terms include a combination of two categories:

- terms relating to the variations of coercive behaviour and controlling behaviour, and

- terms covering broader behaviour conceptualisations associated with coercive control and intimate partner violence/abuse: intimate terrorism, psychological, financial, and reproductive.

Key word searches were conducted in the title, abstract and key word search fields. Appendix B contains the search strategy developed to search the key terms within each of the five databases.

The search was narrowed to articles published since 1 January 2012 to ensure that the literature sampled was recent, while still being able to capture changes in the literature over the past decade. The search was also restricted to Australian research published in English language. Where there is no or limited Australian literature, we supplemented this using international literature identified in the preliminary search (outlined below).

In the second sampling step, all studies obtained through the first step were used as potential sources for further sampling. A hand search of each reference list was conducted to identify other relevant studies. Where relevant to the scope topics, additional material such as legislation and submissions to enquiries and other grey literature were included in the analyses.

The screening process

The literature was screened in two phases: a practical screen and a methodological screen (Fink, 2010).

Practical screen for the usefulness of the literature

The practical screen was the initial assessment of how useful a piece of literature might be to the overall review (Fink, 2010). This assessment was based on a set of predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). The inclusion criteria were divided into three relevant research participant categories: (1) victim-survivors, (2) perpetrators and (3) community. The content focus for each participant category is provided in dot-point format.

For each document identified through the sampling procedure described above, the abstract was examined to determine whether one or more of the necessary inclusion criteria were met. Where articles did not include an abstract, an electronic key term search was conducted, and relevant parts of the document were reviewed to establish the context and purpose of the article. Where an electronic key term search was not possible, the entire document was reviewed to assess suitability.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

Victim-survivors of coercive control

Advocacy efforts to address coercive control | Coercive control outside of the context of domestic and family violence (for example, authoritarian parenting styles, workplace behaviours) |

Perpetrators of coercive control

| |

Community samples

| |

The research team drew on literature from the broader DFV literature in instances where there was little to no research specific to coercive control available for particular subtopics. Selected seminal materials published before 2012 were also included.

Methodological screen for methods used within the literature

The methodological screen was then applied to each of the articles that passed the practical screen, using a second set of inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2). The aim was to prioritise research studies where original quantitative data is reported and the methods are clearly explained. In topic areas where quantitative data was not available or where gaps were identified within the quantitative literature, we turned to the empirical qualitative literature and position papers for insights. Where gaps remained, reports from government agencies and parliamentary inquiries (including for example, Women’s Safety and Justice Taskforce, 2021, 2022, and New South Wales Parliament Joint Select Committee on Coercive Control, 2021) and reports from peak bodies were used. This kind of stepwise hierarchy of article inclusion based on methodology and peer-review is supported in the rapid review guidelines provided by Cochrane (Garritty et al., 2020). The identification of related qualitative studies and reports by peak bodies and government agencies, even if excluded from thematic synthesis of findings in the present review, were still identified in the search process and used to contextualise findings. Finally, review papers were excluded as the articles reviewed may not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the proposed review.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Empirical academic literature reporting original quantitative data (excluding case studies) |

|

| 2 | Empirical academic literature reporting original qualitative data | |

| 3 | Position papers and reports by government agencies and peak bodies |

Data extraction

A data extraction form was used, which included a series of categories that corresponded to the desired participant types (victim-survivors, perpetrators, and community) and thematic topic outlined in the introduction. This extraction form was completed for each article sampled in the review. The categories in the form were tested against each article and evolved through the extraction process to reflect the content and specifics of coercive control research literature. The completed data extraction forms were used to inform the thematic analysis of the review.

Report structure

This report will present the literature review in 14 further sections. Section 2 presents the defining features and elements of coercive control in the DFV context. Section 3 presents research relating to prevalence and this is followed in section 4 by a discussion of the gendered and intersectional drivers. Section 5 outlines the experiences of coercive control by victim-survivors and perpetrators, before the short- and long-term impacts of coercive control on victim-survivors, families and communities are presented in section 6. Research literature relating to community awareness of coercive control will be presented in section 7, and an analysis of research relating to the experiences of coercive control by particular groups (including those affected by discrimination and inequality) follows in section 8. Sections 9 and 10 consider the limited available research on help-seeking behaviour and the effectiveness of current approaches in addressing coercive control, including the experience of, and access to, support for perpetrators. Section 11 then focuses on the effectiveness of police responses and subsequently discusses police workforce development and training, which is followed by a similar discussion on development and training in the health sector in section 12. Section 13 explores considerations relating to the criminalisation of coercive control and the potential unintended consequences that may result, including misidentifying victim-survivors as perpetrators and the risk of increasing the over-representation of First Nations people in the criminal justice system. A summary and conclusion of the material examined overall in this literature review is presented in section 14.

2. Definitions of coercive control

Research on DFV is increasingly focusing attention to the role of coercively controlling behaviour, recognising such patterns of behaviour as a means to control, intimidate, and limit the autonomy of the victim-survivor (Australian Women Against Violence Alliance, 2021). Notably, much of the literature focuses on coercive control within the context of IPV. Although this literature review is largely focused on the research evidence within an IPV context, it is important to acknowledge that children and young people are a focus, and that there are also some important distinctions within specific bodies of literature, including research on reproductive coercion, and experiences of coercive control within LGBTIQ+ communities (for example, Hill et al., 2020; Tarzia et al., 2019).Research on these experiences illustrates how victimisation and perpetration of coercive control can also be shaped by complex familial relationships and external influences such as heteronormativity and expectations about rigid gender roles. These nuances will be examined more closely in the corresponding sections on these topics.

The concept of coercive control has roots in feminist scholarship established in the 1970s and 1980s (Langdon et al., 2022) which started to point to non-physical forms of violence as a tactic used by perpetrators to control victim-survivors of DFV (for example, Dobash & Dobash, 1979; Schecter, 1982). Coercive control manifests in different ways according to the relationship context. However, Evan Stark’s (2007) seminal scholarship represents a key turning point for research in this area, further developing our understanding of coercive and controlling behaviours in intimate partner relationships as not necessarily co-occurring with physical violence. For Stark, coercive control is a framework of abuse that erodes a victim-survivor’s autonomy and agency (Stark, 2007): it is not simply “a type of violence” (Stark & Hester, 2019, p. 81). According to Stark (2007), coercive control is a way for perpetrators to micromanage the daily life of their partners, and this can be achieved through a range of behaviours, such as: physical violence; emotional or psychological abuse; sexual violence; stalking and surveillance; social isolation; financial abuse; technology-facilitated abuse1 and systems abuse.

Despite this development in thinking, there is still no single agreed definition of coercive control.Some research defines coercive control as the broader context in which abuse occurs, and other studies frame coercive control as a tactic in and of itself. Nevertheless, the empirical research identifies a range of common behaviours that emerge, providing a framework through which coercive control can be identified and measured. Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS, 2021) provides some key considerations in defining coercive control that align with Stark’s conceptualisation.ANROWS describes coercive control as the overarching context in which DFV occurs as distinct from a tactic used to perpetrate DFV. More specifically, ANROWS defines coercive control as “a course of conduct aimed at dominating and controlling another (usually an intimate partner but can be other family members)” (ANROWS, 2021, p. 1). ANROWS also describes it as a kind of male power where physical and non-physical violence tactics are used to subordinate and control the female victim-survivor (ANROWS, 2021).

There is also broad agreement that coercive control is not simply a form of emotional abuse (although emotional abuse can be a part of coercive control) and that it is defined by ongoing patterns of behaviours utilised by the perpetrator to control the victim-survivor that are unique to the relationship (ANROWS, 2020). As coercive control is cumulative and individualised rather than being an isolated incident (ANROWS, 2021; Douglas & Fitzgerald, 2022), it can be difficult to identify outside of the relationship as domestic violence (Boxall & Morgan, 2021; Douglas, 2021). Threats may be implicit or explicit (Bendlin & Sheridan, 2019) and do not have to be followed through in the context of coercive control, as the fear and belief that the acts will be committed result in the cooperation of victim-survivors (Johnson et al., 2019). The belief that these threats will be perpetrated give rise to the term ‘intimate terrorism’ which emphasises the use of fear to control victim-survivors (Boxall & Morgan, 2021).On the other hand, Cleak and colleagues (2018) cite the use of physical forms of violence when non-physical tactics are not effective, creating an “abusive pattern” (p. 1,120) which is again often difficult to reveal and measure.

According to ANROWS, definitions of coercive control should centre on the ways that ongoing, repetitive, and cumulative DFV tactics impact a person’s autonomy, liberty, and equality (ANROWS, 2021). The focus should not be exclusively on violent behaviours and individual incidents (ANROWS, 2021) given that the perpetrator’s dominance and control over the victim-survivor has the potential to impact “every aspect of her [or their] life, effectively removing her personhood” (ANROWS, 2021, p. 1). The range of physical and non-physical behaviours noted above can be used separately or together across different contexts. ANROWS emphasises the use of coercive control as involving an intent to diminish the agency of the victim-survivor and create a sense of entrapment in the relationship (ANROWS, 2021). Similarly, Bendlin and Sheridan (2019) identify the use of coercive controlling behaviours as a means of either provoking or diminishing a specific response from the victim-survivor, controlling their emotions and entrapping them in the relationship. The enumerated behaviours are not exhaustive, as perpetrators can adopt a broad range of tactics and behaviours contextualised to the relationship to evoke fear in the victim-survivor (Boxall & Morgan, 2021).

The measures for coercive control applied in an online survey (involving 15,000 women aged 18 years or over) conducted by the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC), includes in the definition of coercive control, three or more forms of the following emotionally abusive, harassing and controlling behaviours in the three-month period preceding the survey (Boxall and Morgan, 2021, p. 3):

- physical and/or sexual violence

- jealousy and suspicion about friends, family and social connections

- social isolation whereby perpetrators interfere in victim-survivor’s social relationships and prevent victim-survivors from maintaining relationships

- monitoring and surveillance of where victim-survivors are and what the person is doing, including stalking

- financial abuse, including where perpetrators control all of the income, pressuring victim-survivors to spend money and/or limiting victim-survivors’ ability to obtain employment

- damaging or stealing property in order to intimidate victim-survivors

- emotional and psychological abuse, including threatening behaviours, verbal abuse, threats of self-harm and/or harm to others, humiliation, eroding victim-survivor’s self-esteem and sense of identity, and

- utilising technology to enact coercive control through monitoring and surveillance, restricting the use of technology to increase isolation and disconnection from friends and family.

1 Technology-facilitated abuse involves the ‘use of mobile and digital technologies in interpersonal harms such as online sexual harassment, stalking and image-based abuse’: Powell, A., Flynn, A., & Hindes, S. (2022). Technology-facilitated abuse: National survey of Australian adults’ experiences (Research report, 12/2022). ANROWS. See also Department of Social Services (2022). National action plan to end violence against women and children 2022-2032: Ending gender-based violence in one generation.

www.dss.gov.au/women-programs-services-reducing-violence/the-national-plan-to-end-violence-against-women-and-children-2022-2032

3. Prevalence of coercive control

This literature review indicates that there is limited evidence on the experiences and perpetration of coercive control in Australia (rather than DFV more broadly). Consequently, there is no reliable prevalence data on coercive control. Although many behaviours associated with coercive control are measured or discussed in the studies referred to in this literature review, most studies do not refer to coercive control specifically.

Limited research has focussed specifically on samples of people who have experienced DFV to identify the nature of experiences of coercive control. One study undertaken by Reeves and colleagues (2021) presents data collected through an online survey directed at Australians who had experienced coercive control in a DFV context. The final sample of research participants comprised 1,261 responses.Most participants identified as female (82%), with 16% identifying as male and 2% selecting “other”. The findings indicate that 80% of participants reported experiencing intimidation, 79% had experienced humiliation and degradation, 79% had been isolated from their family and friends and 64% had rules applied to their day-to-day living by their abuser (Reeves et al., 2021). Almost two-thirds reported limitations on their access to money and finances and other forms of economic abuse (64%) and the infliction of rules on their day-to-day living (64%) (Reeves et al., 2021). More than half reported threats of harm if they did not comply with their abuser’s rules (52%) (Reeves, et al., 2021). In relation to perpetrators, 87% of participants reported experiencing coercive control from a former partner and 10% from a current partner.

Another study conducted by Boxall and colleagues in 2020 involved the analysis of data from the AIC online survey sent to women members of the i-Link Research Solutions online panel of adults between May and June 2020. The survey methodology involved proportional quota sampling with the data being weighted according to age and jurisdiction to reflect the Australian population (Boxall et al., 2020). Nevertheless, because a non-probability sampling method was used, the authors cautioned that the survey findings could not be generalised to the population of Australian women (Boxall et al., 2020). The survey aimed to explore the nature and prevalence of domestic violence experienced by women in Australia during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and any causal mechanisms between the pandemic and domestic violence. Participants were asked to reflect on their experiences of domestic violence in the three months preceding the survey, together with prior experiences of DFV (Boxall et al., 2020, p. 2). The data showed that 12% of all participating women and 22% of which were in cohabiting relationships reported experiencing “emotionally abusive, harassing and controlling behaviours”. Boxall and colleagues also indicate that 6% of all participating women and 11% who were in a cohabiting relationship experienced coercive control, which was defined for this survey as involving experiences of three or more forms of the emotionally abusive, harassing and controlling behaviours listed in section 2 above in the three-month period preceding the survey (Boxall et al., 2020, p. 3).Almost half of the women reported emotionally abusive, harassing or controlling behaviour, including “constant verbal abuse and insults” (47%) and “jealousy or suspicion about…friends” (46%) as most common.Two-thirds (67%) of women who reported emotionally abusive, harassing or controlling behaviour in this period reported more than one form of emotionally abusive, harassing, or controlling behaviour. On average, nearly four types of emotional abuse, harassing or controlling behaviours were reported by victim-survivors (Boxall, et al., 2020, p. 8).

Another recent study by Mayshak and colleagues (2020), involved a cross-sectional survey of 1,009 Australian adults (aged 18-79 years). Of the 989 participants who responded to questions about coercive control in the survey, 28% (n = 276) experienced coercive control over the past 12 months from a current or most recent partner.2 (Mayshak et al., 2020).

Insights are also available from the New South Wales Domestic Violence Death Review which presents data from 112 intimate partner homicides that occurred in New South Wales between March 2009 and June 2016, involving the death of 93 women and 19 men (Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Team, 2020).The review indicates that in all but one of the 112 cases in this dataset (99%), “the relationship between the domestic violence victim and the domestic violence abuser was characterised by the abuser’s use of coercive and controlling behaviours” (p. 154). In each of these cases the domestic violence abuser perpetrated various forms of abuse against the victim-survivor, including psychological abuse and emotional abuse. The findings indicate that 99% of homicides caused by IPV between 2008-2016 show evidence of coercive control (Domestic Violence Death Review Team, 2020).

In a study based on police administrative data, Bendlin and Sheridan (2019) reviewed a sample of 9,884 Family Violence Incident Reports involving stalking behaviour from the Western Australia Police Force made between 2013-2017. The study examines the link between non-fatal strangulation and other coercive and controlling behaviours and focuses on reports where stalking was indicated, as the presence of other coercively controlling behaviours is often seen among this population (Bendlin and Sheridan, 2019).The study applies the Dutton and Goodman (2005) model of coercive control, which is described as a multifaceted concept that “involves behaviours such as isolation, intimidation, excessive monitoring, and threats… (with) a negative consequence…instigated towards the victim...as a result of a previous threat to give credibility to future coercive control and to ensure that such acts are effective in asserting compliance” (Bendlin and Sheridan, 2019, p. 5). The study focused on Family Violence Incident Reports (FVIR) completed by police officers in Western Australia when called to “a domestic disturbance”, involving stalking or where stalking was indicated (Bendlin and Sheridan, 2019, p. 10). These FVIRs are completed based on information drawn from police questioning, i.e. victim-survivor accounts. The descriptive summary data indicate that 44% of the reports in the sample involved the presence of coercive control in the relationship pertaining to the FVIR (Bendlin & Sheridan, 2019, p. 27, Table 1). However, it is important to note that due to the authors narrow sample (reports where stalking was reported), increased rates of coercive control may be identified should the scope be expanded to include instances of coercive control where stalking was not involved.

Data collected by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) via the Personal Safety Survey (PSS) also provides key insights into experiences of coercive control, through the lens of emotional abuse. The ABS define emotional abuse as “behaviours or actions that are aimed at preventing or controlling [someone’s] behaviour, causing them emotional harm or fear” (ABS, 2022). The PSS is a national survey based on responses from 21,242 participants, with 15,589 of these respondents being women. Analyses indicated that nearly one quarter (23%) of Australian women had experienced emotional partner abuse since 15 years of age, with 6.1% of women experiencing partner emotional abuse at the hands of a current partner, and 18% experiencing this abuse by a previous partner. The most common forms of emotional abuse for the 6.1% of women who experienced this from a current partner, were threatening or degrading behaviours (76%) and controlling financial behaviours (41%). For the 18% of women who had experienced emotional partner abuse by a previous partner, 88% had been subject to threatening or degrading behaviours and 63% had experienced controlling social behaviours. In relation to the number of behaviours experienced by these women who had been abused by a current partner, nearly half (45%) had experienced only one behaviour, and a quarter (25%) had experienced two behaviours. For the women who had experienced emotional partner abuse by a former partner, 18% experienced one behaviour. Strikingly, 20% of women who had experienced emotional partner abuse from a former partner had experienced 10 or more behaviours (ABS, 2022).

2 The scale assessing psychologically controlling behaviour in Mayshak et al., 2020 is based on Johnson & Leone, 2005 and includes seven questions regarding experiences of controlling behaviour in the past 12 months including: whether the partner limits contact with family or friends; whether the partner makes the participant feel inadequate; and whether their partner is jealous or possessive (Mayshak et al., 2020, p. 3).

4. Gendered and other intersectional drivers of coercive control

Coercive control is a gendered phenomenon as it (re)produces power imbalances and inequalities stemming from gender structures and norms (ANROWS, 2021; Harris & Woodlock, 2019). Coercive control also occurs in the context of other intersectional inequalities, such as race, age, sexuality and sexual identity, location, and disability (Douglas et al., 2019).

In their framework for the primary prevention of violence against women in Australia, Our Watch (2021b) highlight the importance of understanding the gendered dynamics of family violence in Australia, with the definition of family violence adopted in the framework including coercive and controlling behaviour (Our Watch, 2021b, p. 61).The gendered dynamics include the gendered nature of both victimisation and perpetration, and identify a socio-ecological model of violence against women as supporting prevention work with the focus on the “structures, norms and practices” that drive perpetration of violence and enable it to occur “at different levels of the social ecology” (Our Watch 2021b, p. 34).

Gender inequality is still prevalent in Australian institutions, with men continuing to hold the majority of power and influence in workplaces, as well as legal and political systems (Our Watch 2021b). Moreover, in relation to Australian public attitudes to gender dynamics in the household, findings from the 2017 National Community Attitudes towards Violence Against Women survey (2018), show that “one in five Australians think men should take control in relationships and be the head of the household” (Our Watch 2021b, p. 29).

Attitudes that reinforce rigid gender roles and stereotypes are linked to attitudes that support violence against women (Our Watch, 2021b). Characteristics of masculinity that are constructed as dominant in Australia include entitlement, control, hypersexuality, aggression and toughness, competitiveness and risk-taking (Our Watch, 2021b, p. 31), and influence how men and boys feel they should behave. While not all the characteristics of masculinity have negative connotations, they can serve to maintain gender inequalities and reinforce men’s power and dominance over women (Our Watch, 2021b).

This conceptual framework also recognises that gendered drivers, together with other drivers, are relevant in some intersectional contexts also. Our Watch identifies the four key drivers as:

- Condoning violence against women

- Men’s control of decision-making and limits to women’s independence in public and private life

- Rigid gender stereotyping and dominant forms of masculinity, and

- Male peer relations and cultures of masculinity that emphasise aggression, dominance and control (Our Watch, ANROWS & VicHealth, 2015, p. 36).

Gendered and other intersectional inequalities shape experiences of coercive control. For example, a qualitative study by Louie (2021) based on interviews conducted in 2018 with Melbourne-based DFV practitioners (n = 13) found that women are more likely to experience economic abuse if they have a disability or long-term illness, or experience financial stress. Research by McKenzie and Kirkwood (2016) analysed 51 Victorian cases where men killed an intimate partner and observed how gender attitudes shaped risk factors in intimate partner homicide. The analysis also identified that in over one-third of cases (n = 19) in the sample, there were three or more co-existing factors, including perpetrator mental health issues or substance misuse (McKenzie & Kirkwood, 2016, pp 15-16). Maher and colleagues (2018) also examined the compounding risk factors of women with disability in facing economic stressors, such as housing security and access to support services. As highlighted by Moulding and colleagues (2021), based on mixed-method research involving a national online survey and life history interviews, gendered drivers were identified as manifesting in men through expectations placed upon them and roles (Maher et al., 2018). For men facing unemployment, this may result in higher risks of domestic violence due to beliefs about masculinity or stemming from jealousy if their partner is earning more (Maher et al., 2018). However, as noted by Moulding and colleagues (2021), further research is required to gain greater understanding of the gendered drivers of DFV in the Australian context.

Limited research has explored coercive control experienced by LGBTIQ+ people. LGBTIQ+ people represent a varied and diverse population. Relationships may have only one person who is either L,G,B,T,I, or Q, they may involve people of same or mixed sex, they may be defined as heterosexual (regardless of people’s individual sexuality), and people may hold one or more identities.However, some research which explored violence in intimate partner relationships amongst LGB and/or T + people, found that patriarchal heteronormativity and cisnormativity is relevant to their experiences of coercively controlling partners (Donovan & Barnes, 2020). Donovan and Barnes (2020) found that beliefs and/or expectations that a heteronormative, cisnormative binary of relationship roles/norms that map onto male/female, victim/perpetrator binaries provided a template for understanding the abuse of power that had taken place in LGB and/or T people’s relationships. They argued that male participants’ narratives demonstrated that their socialisation into heteronormative and cisnormative masculinity had normalised physical violence between men as a way of responding to conflict. Further, Donovan & Barnes (2020) found that patriarchal gender norms shape how gay men might treat each other, both inside and outside of intimate relationships, and that patriarchal norms can make it difficult for gay men to problematise their own behaviour as well as to recognise their experiences as being contextualised in a coercively controlling relationship (Donovan & Barnes, 2020).

5. Experiences of coercive control by victim-survivors and perpetrators

The following section highlights literature pertaining to the experiences of coercive control by victim-survivors and perpetrators. Understanding the lived experience of both victim-survivors and perpetrators is important to inform strategies to better identify and address coercive control in future.

Victim-survivor experiences

Coercive control includes a broad range of tactics and behaviours that perpetrators utilise to control and micro-manage the life of their partners. A limited amount of Australian research explores the ways that victim-survivors experience coercive control (Bendlin & Sheridan, 2021; Boxall, et al., 2020; Boxall & Morgan, 2021; Buchanan & Humphreys, 2020; Carrington et al., 2021; Mayshak et al., 2020; Moulding et al., 2021; Pitman, 2017).

For example, Boxall and colleagues’ (2020) analysis of data from the AIC online survey noted above, identifies that the most common forms of abuse that women report are verbal abuse and insults, jealousy, and monitoring or surveillance (Boxall et al., 2020, p. 8). Two-thirds of victim-survivors report experiencing more than one form of emotionally abusive, harassing, or controlling behaviour (Boxall et al., 2020, p. 8). Financial abuse is experienced by one in two participants, while two in three participants indicate that they had been verbally abused or experienced constant insults in order to make them feel intimidated by the perpetrator (Boxall et al., 2020, p. 7). Threatening behaviours are also directed towards others in the victim-survivors life, such as their children, friends, family, and pets (Boxall et al., 2020).

A subsequent study drawing from the same dataset (Boxall and colleagues, 2020) reveals the high prevalence of jealous behaviour and suspicion of friends and family members by perpetrators, with 55.9% of women reporting experiencing coercively controlling behaviour (n = 388), including their partner monitoring how they spent their time (Boxall et al., 2021). Further, 43% of women reported damage, destruction or theft of their property, perpetrated by their partner. In the context of coercive control, damaging property and the abuser’s use of physical strength against an object (for example, by punching a wall) may be used to intimidate by demonstrating their ability to harm their partner (Boxall and colleagues, 2021). However, these behaviours may also be used as a form of financial abuse against women, particularly when they are forced to repair or replace damaged goods at their own expense (Boxall & Morgan 2021). Women also reported that their partner isolated them from their family members, friends and other sources of help, restricting their use of their phone, internet or car (Boxall and colleagues 2021). Constant insults, belittling, yelling or verbal abuse was reported by 67% of women, which they describe as a means to humiliate or intimidate them (Boxall and colleagues, 2021).

As indicated in section 4 above, the national PSS also highlights the experiences of many Australian women of coercive control through the lens of emotional abuse. The most common forms of emotional abuse being threatening or degrading behaviours, controlling financial behaviours and controlling social behaviours (ABS, 2022).

Earlier research by AIFS - the Experiences of Separated Parents Study (ESPS) - a component of the Evaluation of the 2012 family violence amendment reforms, which was based on data from telephone interviews with separated parents (2012: n = 6,119; 2014: n = 6,079), provides insight into the experiences of coercion and control. The 2014 survey includes additional questions based on the amended definition of family violence in s 4AB of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) (FLA), which includes behaviour that “coerces or controls” a family member or “causes the family member to be fearful”. It should be noted that these findings are based on participants’ understandings of these terms and their application to their own subjective feelings. The data from the ESPS indicate that feeling fearful, coerced, or controlled is more commonly reported by parents who had experienced physical violence. Further, there are statistically significant differences between mothers and fathers who report feeling fearful, coerced, or controlled and physical violence or emotional abuse, with the former consistently more likely to report experiencing safety concerns than participants who were fathers (Kaspiew et al., [AIFS], 2015, Tables 3.9 and 3.10, p. 45-46). The data also show that mothers are more likely than fathers to report feelings of coercion and control before or during separation (Kaspiew et al., [AIFS], 2015, Figure 3.14, p. 47) and mothers’ reports regarding the severity of feeling fearful, coerced, or controlled are also substantially higher than those made by fathers (Kaspiew et al., [AIFS], 2015, Figure 3.16, p. 51). Also of note, significantly higher proportions of mothers using formal pathways to resolve their parenting arrangements report experiencing family violence before or during separation that cause them to feel fearful, coerced, and controlled – 71% for family dispute resolution (FDR) and 86% for courts – compared to fathers – 48% FDR and 55% courts (Kaspiew et al., [AIFS], 2015, Figure 4.4, p. 80). These gender differences are also present among parents reporting experiences of fear, coercion, and control since separation although not as pronounced as those experienced before or during separation (Kaspiew et al., [AIFS], 2015, Figure 4.5, p. 81).

A study by Pitman (2017), which analysed the experiences of 30 Tasmanian women experiencing domestic violence, found that women perceived their partners (who were also the perpetrators of the violence they experienced) to share an attitudinal style of superiority and entitlement. Participating women describe being made to feel inferior and expected to adjust and adapt to their partner’s needs.Consequently, they recall feeling reduced to being an extension of, and a possession of their partner (Pitman, 2017). Participating women also explained how the attitudinal style of their partner created “adversarial communication” and “behaviour patterns”, inconsistent with an egalitarian relationship and clear boundaries (Pitman, 2017). For example, women recounted how their partners withdraw, refuse to communicate, withhold necessary information, empathy or reassurance, and generally avoid their responsibilities (Pitman, 2017). Pitman’s study also presented women’s experience of coercive control in the context of ‘double standards’, where their partner denied that they have the same rights as they do and refused to meet their needs or to be accountable for their actions.

Qualitative studies by Moulding and colleagues (2021) and Pitman (2017) examine Australian women’s experiences of coercive control. Through in-depth interviews with 17 Australian women, Moulding and colleagues (2021) found that women report experiencing a loss of freedom and identity, work, social connections and housing. Women describe perpetrators preventing them from contacting family or friends, having their appearances controlled, as well as experiences of surveillance and stalking (Moulding et al., 2021). Participants in the study describe a loss of self-esteem and self-confidence, with many identifying tactics of coercive control leading to a loss of self (Moulding et al., 2021). Similarly, Pitman’s study (2017), discussed in section 3, provides insight into victim-survivors’ experiences of a loss of autonomy and agency, with many feeling ‘trapped’ within their relationship (Pitman, 2017). Participants also report being treated as inferior and as if they were a possession of the perpetrator (Pitman, 2017).

Technology-facilitated abuse

There is a growing body of Australian literature examining the use of technology to facilitate coercive control. Technology-facilitated abuse co-occurs with other forms of coercive control, often utilised as a means of controlling and monitoring aspects of a person’s life such as their finances and communication. It is also used to impersonate, create barriers to access help or services, interfere in communication between victim-survivors and children, or to facilitate threatening behaviours (E-Safety Commissioner, 2020).

A recent qualitative study by Douglas and colleagues (2019), based on interviews with 65 women at multiple points over a three-year period, identifies technology-facilitated abuse as a common aspect of victim-survivors experience of coercive control. A total of 85% of participants report this abuse as part of a pattern of violence they experience. These findings are supported by Harris and Woodlock (2019), whose mixed-method study involving focus groups with DFV sector professionals, an online survey of DV support practitioners (n = 152), and an online survey of victim-survivors (n = 46), shows a high prevalence of the use of technology in the pattern of coercive control as a means of monitoring, controlling, and intimidating victim-survivors. Additionally, a smaller qualitative study by Harris and Woodlock (2021) highlights how technology can exacerbate the fear created through coercive control, by creating a “sense of omnipresence” which entraps the victim-survivor further (p. 387).

Another qualitative study, involving interviews with 20 victim-survivors and focus groups with DFV professionals located in rural, regional, and remote New South Wales and Queensland, finds that technology-facilitated abuse does not end at separation (Dragiewicz et al., 2019). Indeed, 12 of the professionals in this study report that they are aware of this abuse occurring during the relationship and confirm that it increases following separation. More specifically, technology-facilitated abuse continues to occur in the context of post-separation parenting with 13 victim-survivors reflecting on this experience. Participants reported experiences of repetitive and persistent text messages and calls, restricting and controlling access to technology, accessing accounts without permission, and impersonation through technology, among many other forms of technology-facilitated coercive control (Dragiewicz et al., 2019). Non-consensual smartphone recordings are also identified in a qualitative study (n = 65), with victim-survivors describing this experience as intimidating (Douglas & Burdon, 2018). However, this research also indicates that non-consensual smartphone recordings can be used by victim-survivors to assist them in protecting themselves and using recordings as evidence of such abuse occurring, highlighting the complexities around this practice from a legal perspective (Douglas & Burdon, 2018).

Children can also be impacted by technology-facilitated coercive control. Dragiewicz and colleagues (2022) utilise data from a qualitative study on victim-survivor’s experiences to analyse children’s involvement in technology-facilitated coercive control. The study found that children can be used by perpetrators to extend coercive control of the family (Dragiewicz et al., 2022). Examples are provided of perpetrators using children to transport devices which can then be used to monitor and track mothers and children, using video calls to obtain information about their location, and using technology to harass and intimidate children (Dragiewicz et al., 2022).

Non-fatal strangulation

There is a growing body of literature on the use of non-fatal strangulation perpetrated in the context of coercive control. For example, Bendlin and Sheridan’s (2019) study, noted in section 3, on the link between stalking behaviours and non-fatal strangulation, based on the 2013-17 dataset of Western Australian Police FVIRs (n = 9,884), found victim-survivors were 2.3 times more likely to report non-fatal strangulation with partners who are coercive, compared with those who do not report coercively controlling partners. The research highlighted the relationship between non-fatal strangulation and coercive control, notably jealous and stalking behaviour, and physical violence to control and threaten the life of the victim-survivor.

Boxall and Morgan’s (2021) analysis of the AIC survey data also highlighted the risk of more severe forms of physical violence (such as non-fatal strangulation) as a method of coercive control. Overall, one in two women participating in the survey who were experiencing coercive control,3 reported that their partner had been physically violent towards them in the three months preceding the survey (Boxall & Morgan, 2021, p. 9). More specifically, 27% of participating women who experienced coercive control reported non-fatal strangulation by their partner, and 23% reported being assaulted by being hit with something that could hurt them, being beaten, stabbed or shot with a gun (Boxall & Morgan, 2021, p. 9).

Douglas and Fitzgerald (2022) further contend that non-fatal strangulation be considered an extreme form of coercive control as it enables the perpetrator to threaten the victim-survivor, often without leaving a mark. Drawing from an original study conducted with 65 women victim-survivors of IPV in Brisbane, the researchers analysed a subset of responses from 24 women who had experienced strangulation, choking, or being grabbed by the neck in the previous 12 months. Findings from the subset revealed the co-occurrence between non-fatal strangulation and coercively controlling behaviours, as physical violence is described by participants as being part of a broader pattern of control (Douglas & Fitzgerald, 2022). The study also illustrated the effect of non-fatal strangulation on victim-survivors’ memory, which impacts the ability to provide statements and evidence during prosecution. Some research, primarily from outside of Australia, has indicated that the consumption of violent pornography may influence similar perpetration of violence against women, though its relationship to coercive control is unclear (for example, Huibregtse et al., 2022).

Coercive control in the context of reproduction, birth and mothering

The literature considered in this review highlights connections between coercive control and decisions and behaviour in relation to reproduction in various ways. Reproductive coercion has been associated with a pattern of coercive control as one aspect of a complex set of dynamics. Other research highlights how coercion and control can manifest in the specific contexts of pregnancy, birth and early parenthood.

A small number of studies on reproductive coercion emerged in the research literature during the initial search conducted for this review. Reproductive coercion is largely considered a form of IPV (Price et al., 2022; Suha et al., 2022; Tarzia et al., 2019). However, Tarzia and colleagues (2019) acknowledge it can be perpetrated by family members. The relevant body of research generally accepts reproductive coercion to include controlling behaviours such as threatening behaviours if the victim-survivor does or does not become pregnant or terminates a pregnancy, tampering with or preventing access to birth control, and sexual assault leading to pregnancy (Price et al., 2022; Sheeran et al., 2022; Tarzia et al., 2019). Further, Tarzia and colleagues (2019) acknowledge the impacts of reproductive coercion on health, including negative impacts to mental health, sexually transmitted infections, and unintended pregnancies. A small number of studies on reproductive coercion emerged in the research literature during the initial search conducted for this review.

The complexities of reproductive coercion are worthy of their own systematic review. Tarzia and colleagues (2019) highlight the difficulties in adequately situating reproductive coercion within IPV. This is because the term reproductive coercion does not accurately account for the sexualised characteristics of this form of abuse, nor does viewing it as sexual violence acknowledge forced reproduction as distinct from forced sex (whereby pregnancy may be an unintended consequence of the latter but is the intent of the former). It is further acknowledged that the role other family members may play in reproductive coercion also places reproductive coercion within the domain of family violence (Tarzia et al., 2019). However, tactics evident in reproductive control often co-occur with those discussed throughout this review and it has been indicated as a form of coercive control (Our Watch, 2021; Parliament of New South Wales, 2020). Similarly, reproductive coercion is defined as a means of maintaining power in the relationship and limiting the autonomy of the victim-survivor through the control of their reproductive health (Price et al., 2022).

A study conducted by Price and colleagues (2022) examined the prevalence of reproductive coercion among a sample of women in Queensland experiencing an unintended pregnancy between January 2015 and June 2017 (n = 3,117). The study findings revealed 5.9% of women reported reproductive coercion and among these women 55.2% reported also experiencing domestic violence. However, the authors note the limitations of the study, which does not capture the experiences of women who carry their pregnancy to term, suggesting the prevalence of co-occurring domestic violence and reproductive coercion could be higher. This is supported by Sheeran and colleagues’ (2022) study on reproductive coercion and abuse prevalence among women who seek pregnancy counselling. Collecting data from two prominent pregnancy counselling providers in Australia, the study revealed that of those who had contacted pregnancy counselling (n = 5,107) 15.4% experienced at least one form of reproductive coercion and abuse (Sheeran et al., 2022). The study also shows that 2% of participants experienced both coercion towards terminating the pregnancy and also coercion towards pregnancy, suggesting reproductive coercion may change over time and contexts (Sheeran et al., 2022).

A qualitative study by Buchanan and Humphreys (2020) provides some further evidence on coercion in the context of pregnancy and mothering.It involved interviews and follow up focus groups with 16 women in Australia who had left an abusive partner between one to eight years prior to interview and had a child under ten years of age. The study aimed to understand the experiences of women who have gone through pregnancy and mothering while experiencing domestic abuse. Research questions were directed at identifying “the cues, from women’s lived experiences, [that] indicate that coercive control is being exerted by their partners” (Buchanan & Humphreys, 2020, p. 325). Women in the study reported experiences of perpetrators refusing to attend ante-natal appointments, showing a lack of interest in the pregnancy and negative attitudes towards a woman’s changing body shape (Buchanan & Humphreys, 2020). Conversely, other women reported perpetrators controlling and micro-managing appointments and decision-making. Three women reported perpetrators preventing them from accessing healthcare during the pregnancy. Women provided accounts of feeling unsupported while giving birth, being manipulated and demeaned during the birth, and feeling pressure to prioritise the needs of the perpetrator even while giving birth (Buchanan & Humphreys, 2020). Victim-survivors describe these coercive and controlling behaviours as being overlooked by hospital staff when perpetrators made displays of “proud fatherhood” (Buchanan & Humphreys, 2020, p. 330).

Impact of COVID-19 on coercive control

Recent research literature focusses on the experiences of victim-survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia (Boxall, et al., 2020; Boxall & Morgan, 2021; Boxall & Morgan, 2021a; Carrington et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic created an environment whereby victim-survivors spent more time in the home with perpetrators, and households were experiencing greater levels of stress and financial strain (Boxall et al., 2020; Carrington et al., 2021).

A cross-sectional survey of female survey adult participants drawn from the research company i-Link’s online panel (n = 15,000) by Boxall, Morgan and Brown (2020), found more than a third of women (36.9%) had at least one experience of wanting to seek advice or support in relation to abuse but could not do so due to safety concerns (Boxall et al., 2020). Boxall, Morgan and Brown (2020) are unable to establish a cause-effect relationship between COVID-19 and an increase in coercive and controlling behaviours, however their findings indicate that social isolation and increased time spent at home and financial hardships from lockdowns, have likely contributed to experiences of physical and sexual violence and coercive control (Boxall et al., 2020). In their study on COVID-19 and DFV services, Carrington and colleagues (2021) highlight shifts in behaviours related to coercive control. Notably, they identified that technology-facilitated abuse was used to monitor and control the victim-survivor during the pandemic. Drawing on data from an online survey conducted in 2020 with 362 participants, the study highlights the growing use of technology in domestic violence and coercive control, and the rising number of new tactics used by perpetrators to control victim-survivors, such as strangulation and COVID-19 lockdowns to control movement (Carrington et al., 2021). Carrington and colleagues (2021) suggest that restrictions on movement during COVID-19 were ‘weaponised’ by perpetrators, with practitioners reporting that the use of coercive and controlling behaviours by perpetrators increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (Carrington et al., 2021). Participants indicated that victim-survivors were experiencing increased isolation, surveillance and fear, alongside feeling unable to seek outside help (Carrington et al., 2021).

Perpetrator experiences

There is limited Australian research investigating the experiences of perpetrators who choose to use coercive and controlling behaviours. The review identified a limited number of small-scale studies that shed light on perpetrator behaviour, with only one study based on data collected from perpetrators themselves. This body of evidence underlines the association between coercive control and femicide, and coercive control and tactics that undermine mothering capacity.

A study by Johnson and colleagues (2019) examined the histories of 68 men who had been convicted of intimate partner femicide. The study reported increased levels of coercive and controlling behaviours by perpetrators in the lead up to femicide These behaviours included controlling actions, psychological abuse, sexual jealousy and stalking. The authors found that although men with a prior history of IPV are more likely to use coercive and controlling behaviours, these behaviours are still common in men with no history of IPV (at 62% of men) (Johnson et al., 2019). These findings point to the importance of understanding the role of coercive control in femicide.

Through in-depth interviews with 17 Australian men, Heward-Belle (2017) collected and analysed data from perpetrators themselves about their use of coercive control. Participants in the study were all involved in a Men’s Behaviour Change Program. They were either on a waitlist to engage in the program or had completed a number of sessions already. To be involved in the study, participants had to be over 18 years old and have resided with their children and the children’s mother for at least one year (Heward-Belle, 2017). This study found that a common tactic used by perpetrators is targeting women’s mothering in order to impact the woman’s self-esteem and sense of identity, as well as fracturing the mother-child relationship (Heward-Belle, 2017). Men in the study acknowledged using such tactics, understanding the effectiveness of undermining a woman’s parenting (Heward-Belle, 2017).

These findings are consistent with a study by Kaspiew and colleagues [AIFS], (2017) that sought to understand the characteristics of perpetrators as fathers and how mother-child relationships are impacted by domestic abuse. As part of this research, 50 qualitative interviews were conducted with women who had experienced domestic and family violence. Of the sample, 37 women reported experiencing coercive and controlling behaviours prior to separation, while 16 reported that these behaviours started after separation (Kaspiew et al., [AIFS], 2017). The participants reported common characteristics of perpetrators such as manipulative behaviours, needing to be in control, prioritising themselves over children or partner’s needs, as well as intimidating and threatening children (Kaspiew et al., [AIFS], 2017).It was found that perpetrators used abusive tactics to undermine the mother-child relationship and two-thirds of women reported that these tactics had continued or escalated after separation (Kaspiew et al., [AIFS], 2017).

As noted earlier, Pitman’s (2017) study identified some common elements in the behavioural styles of perpetrators who use coercive control, including an entitled and adversarial attitude, a lack of empathy and consistently violating boundaries in the relationship (Pitman, 2017).

6. Short- and long-term impacts of coercive control