Empowering migrant and refugee women

Supporting and empowering women beyond five-year post-settlement

September 2017

John De Maio, Michelle Silbert, Pilar Rioseco, Rebecca Jenkinson

Download Research report

Overview

This report presents findings from the Empowering Migrant and Refugee Women project, undertaken by the Australian Institute of Family Studies. This study was commissioned by the Department of Social Services (DSS) to build evidence on practical strategies that could empower migrant and refugee women in the areas of women’s safety; economic and social participation; leadership opportunities; and to foster their role in promoting community cohesion. This report explores various aspects of service delivery to migrant women who have been living in Australia for at least five years. It documents the nature and types of service available, and identifies best practice principles and key service gaps in service delivery for migrant and refugee women. This report also outlines key priorities for addressing these service gaps.

Aims and focus of the research

The study focused on two specific cohorts of migrant women who have been in Australia for more than five years. One cohort is former Humanitarian Programme entrants including Woman at Risk visa holders and the other cohort is women who entered Australia on family visas.

The project had the following key aims:

- Improve understanding of the current state of migrant women’s economic and social participation.

- Document the nature and types of services available to these two cohorts of migrant women.

- Assess the extent to which these services/programs are evidence-based or display promising practices.

- Identify best practice and service gaps in relation to services and programs provided to Humanitarian Programme migrants or family stream migrants who have been in Australia for five years or more.

- Provide recommendations on key priorities for government to undertake in filling these gaps.

Research design

The study comprised two distinct components:

- to improve understanding of migrant women’s economic and social participation, which involved secondary analyses of two key datasets: 1) the Australian Census and Migrants Integrated Dataset (ACMID; 2011 Census); and 2) the Building a New Life in Australia (BNLA) dataset; and

- to identify good practice and key gaps in service and program delivery, primary data was collected via: 1) stakeholder consultations (and an Expert Reference Group); 2) an online quantitative survey (n = 129); and 3) semi-structured qualitative interviews (n = 13), with service providers delivering programs and services to migrant and refugee women.

The findings in this report are based on the perspectives of service providers who were asked to reflect on their professional practices and service delivery in the online survey or qualitative interview. Speaking to migrant women themselves about their issues with service delivery access would be a useful future direction to complement this research and further enhance understanding of the service sector.

Key findings

Migrant women’s characteristics and economic and social participation

Secondary data analyses of migrant and refugee women who had been in Australia between five and ten years (at 2011) was undertaken to explore characteristics of women according to visa type, and to compare these women’s characteristics to those of Australian-born women. Even among migrant women who had arrived on humanitarian or family visas there was considerable diversity. However, on average, the migrant women who had arrived on humanitarian visas and had been in Australia between five and ten years, had relatively low levels of English language proficiency and relatively low levels of educational attainment compared to those arriving on family visas. Women who had arrived on humanitarian visas also had the lowest levels of engagement in employment. Levels of English language proficiency and employment participation were higher for those who had been in Australia longer. A significant number of all the migrant and refugee women included in the analyses were not proficient in English after ten years in Australia, particularly among those who arrived on humanitarian visas. Likewise, employment rates remained low for some groups of migrant women relative to Australian-born women, even after ten years in Australia.

Barriers to employment include poor English language proficiency and low education levels, and this was especially so for humanitarian visa holders. The analyses highlight the importance of the uptake of English classes and other forms of education after arrival to help migrant women engage in employment.

The landscape: program and service delivery for migrant and refugee women

Insights gained through the online survey and qualitative interviews highlighted the complexities of service delivery to migrant and refugee women. Clients accessing these services were reported to be facing many challenges, particularly in regard to English language proficiency and lower education levels compared to the Australian-born women. Therefore, a key challenge in providing services to migrant women was the need to accommodate the diverse language needs of these clients through the availability of information in other languages and bilingual workers. Survey participants told us these aspects of service delivery could sometimes be a particular challenge for mainstream service providers.

Survey participants identified a range of barriers that could hinder the uptake of services by migrant women. These barriers include language barriers; family responsibilities and gender roles of migrant and refugee women; the location of services and transport issues; and inflexible service delivery approaches. Lack of awareness of available services and/or confidence in knowing how to access these services was also identified as a barrier. More generally, participants noted the transition from specialist services to mainstream services could prove challenging for migrant and refugee women, due to the diluted level of language and culturally appropriate responses provided by mainstream services. Furthermore, many people do not take up services and rely on other informal support networks (e.g., family support networks and friends).

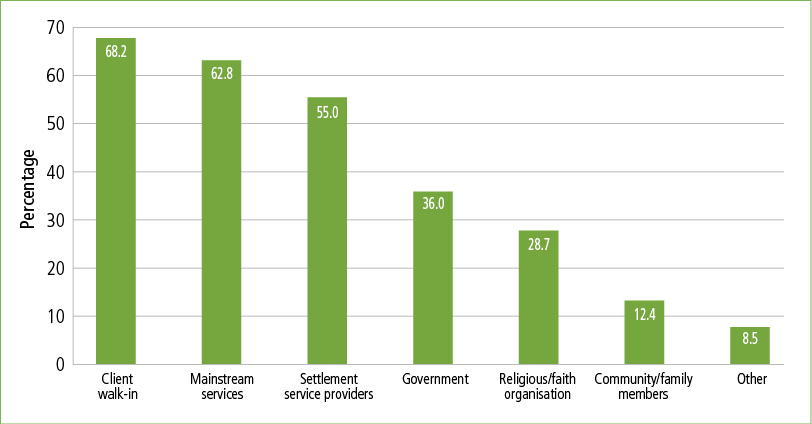

The study revealed a wide variety of program and service types being delivered to migrant women. Most service providers reported that their organisations delivered multiple services to their client group rather than just one dedicated program or service. In terms of how clients were referred to services, service providers reported that clients often directly approached services, without referrals. In some cases, informal referral pathways were also used such as hearing about services from community and family members. Otherwise, formal pathways included referrals from other mainstream services or service providers, and referrals from government.

Evidence-based service delivery and program evaluation

A key aim of the study was to assess the extent to which services and programs were evidence-based. Most survey participants reported that evidence-based practices were a feature of the programs and services delivered to migrant and refugee women. For example, a little over one half of participants reported their service or program was based on an already existing evidence-based program. The majority (around two thirds) reported that aspects of their service, such as program aims and objectives, were documented and readily available to other service providers. A little over three quarters of participants reported that at least one type of evaluation of their program or service had been undertaken to measure impact and client outcomes.

Best-practice principles in service delivery for migrant women and their families

The project aimed to identify best practice in service delivery to migrant women. Five key principles were identified by service providers as being important in supporting migrant women and enhancing service delivery to the cohort.

- Service providers highlighted the need to deliver services in a gender responsive and culturally appropriate manner. While it may seem obvious, it is clearly a central aspect of delivering best practice to migrant and refugee women.

- Culturally competent delivery was also identified as being critical for both engaging clients and maintaining ongoing relationships with their client base. A culturally diverse and bilingual workforce (including the employment of migrant and refugee women themselves) was identified as a key aspect of best practice.

- Survey participants nominated collaboration with other settlement and mainstream service providers as an important mechanism for empowering and supporting migrant women, offering referral opportunities that would not be possible otherwise and ensuring holistic service responses. Collaboration with mainstream services was also vital where migrant women services did not have expertise in a particular area, for example partnering with specialised family violence services.

- Fostering collaborative relationships with migrant and refugee community leaders was also critical as these relationships helped services better understand the needs and experiences of their clients and also served an important purpose in promoting service visibility.

- A strengths-based approach to service delivery harnessed the positives and strengths that migrant women and refugees possess and was another key avenue to empowering these women.

Key gaps in service and program delivery and key priorities to fill these service gaps

An important focus of the study was to explore issues around service gaps and key priorities in the provision of services to migrant women. Five service gaps were identified by service providers, and some priorities were identified to help address each of these gaps.

1. Delivery of services in a gender sensitive and responsive way: Many survey participants noted that cultural norms and gender roles could hinder the uptake of services. Effective service delivery also needs to be attuned to the added family and caring obligations that migrant women were often responsible for. Flexibility in service access, eligibility and delivery options was seen to be an important mechanism to address these issues.

The service providers gave the example of migrant and refugee women experiencing competing tensions between their need to learn English and secure employment and their need to care for family and children. Clients may then commence English classes and seek employment later, after their family is more settled in Australia. These results highlight the importance of flexible program designs that recognise that clients’ needs can vary over time. Along with identifying client needs at intake, regular and ongoing needs assessments could therefore help support effective service delivery to migrant women.

Priorities

The design and delivery of services and programs are provided in a gender responsive way, being mindful of particular gender issues within the cultural context.

While eligible Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) clients can apply for an extension to the five year time limit to commence classes, consideration should be given to making English language classes via AMEP available after five years of settlement to migrant and refugee women with caring responsibilities. This specific recommendation refers to the broader finding that effective service and program delivery requires an understanding of the potential challenges for migrant women in relation to employment and education, given competing priorities of family and child care responsibilities.1

Programs that recognise that clients’ needs vary at different points in the settlement journey and “one size does not fit all”. Identifying client needs at intake and regular and ongoing needs assessments can promote effective service delivery by ensuring that programs and services support clients as their needs evolve over time

2. Cultural competency and mainstream service delivery: Our participants suggested that there was great variation in service providers’ ability to deliver services in a culturally and linguistically appropriate manner within mainstream services. Study participants reported that mainstream service providers may sometimes lack the cultural competency required to provide appropriate support to migrant and refugee women. They may also lack knowledge of cultural and religious differences, which may hinder their ability to provide effective services. The service providers emphasised the importance of training and support for mainstream services to enhance understanding of cultural practices within different ethnic groups, which could then be reflected in their program and service delivery.

Priorities

An increased focus for mainstream service providers on the importance of culturally and linguistically appropriate delivery of services for this client group. This will help to ensure that the needs of refugee and migrant women are supported and achieved.

Training and other supports for mainstream programs and services to further enhance culturally and linguistically appropriate service delivery.

3. Greater visibility and promotion of service accessibility: Barriers to service access were identified as a much greater challenge than the availability of services. While many services provided materials and promotion in languages other than English, language barriers were reported by participants to be the most significant barrier hindering migrant women from accessing appropriate services. Study participants reported that up-skilling former clients and volunteers so that they can assist in the delivery of services is one approach to help address language barriers and culturally competent service delivery. The promotion of services to client groups was seen as important to ensuring that migrant women could access the services they require to support their needs. An offering of outreach services was identified by participants as one way to help promote greater levels of service accessibility to migrant women. This would need adequate resourcing.

Priorities

Priority needs to be given to promoting the visibility and accessibility of existing services to key client groups.

Programs and services are supported to up-skill former clients and volunteers from a refugee and migrant background to assist in the delivery of services. This can help to address language barriers and promote service accessibility.

Programs and services are supported to offer flexible services such as outreach and home visits to help promote accessibility of services to migrant and refugee women.

There is a need for the delivery of program and service promotion in languages other than English to ensure clients are matched to appropriate services and client needs are understood.

4. Transition to mainstream services and the move towards mainstream service delivery in large hubs: The challenges and issues with the transition to mainstream service delivery for migrant and refugee women are those related to gender and culture, as well as the other factors discussed above. The way these services are accessed can be a challenge, with mainstream services increasingly delivered through service delivery hubs, which involves a central intake point that then links or refers clients to other services. While survey participants acknowledged service delivery hubs as an important model, some concerns were raised that this approach had the potential to dilute the cultural and linguistic capacity and flexibility required to provide services and support the needs of migrant and refugee women. Some suggested the move towards more centralised service delivery could also create anxiety and uncertainty for those migrants who lack English language proficiency when they are asked to undertake intake and assessment procedures over the telephone.

Priorities

Further research is needed to explore how best to support migrant and refugee women as they transition from specialist services to mainstream services.

Consideration should be given to providing funding for community and grassroots services to partner with mainstream services to ensure post-settlement needs for migrant women are met.

The provision of funding to ensure migrant and refugee specialists are part of service delivery hubs should be explored.

5. Funding for post-settlement services and reporting requirements: A lack of dedicated funding towards support services for migrant and refugee women in the post-settlement period (that is beyond five years after arrival) was identified as a service gap by the service providers participating in the research. Some service providers noted that they provide support to refugee and migrant women across the settlement spectrum, from new arrivals through to women who have been settled in Australia for up to 20 years. However, there is little to no dedicated funding for targeted services beyond the initial five-year settlement period.

Service providers also reported that existing funding arrangements make it necessary for their organisations to undertake several small grant applications and secure funding from a diverse range of sources in order to maintain their presence in the service landscape and deliver services to their client group. Service providers told us that securing funding for their programs and services via these mechanisms often involved additional reporting and evaluation of outcomes and these requirements divert resources from actual service delivery. To balance the need between reporting requirements and efficient service delivery, further consideration could be given to whether information provided through other reporting mechanisms could streamline reporting requirements for service providers working in this space.

Priorities

Explore options to streamline funding sources and reduce red tape to maximise efficient delivery of services and minimise administrative tasks.

Undertake more focused research to better understand how funding arrangements and the provision of services in the post-settlement period (five years after arrival) can best support migrant and refugee women.

1 At the time of writing, participants in AMEP must commence their tuition within 12 months of visa commencement or arrival in Australia and complete their tuition within five years. See www.education.gov. au/adult-migrant-english-program-0.

The Empowering Migrant and Refugee Women project was undertaken for the Australian Multicultural Council (AMC) to inform their advice to government on practical strategies to empower migrant and refugee women.

This research focuses on two specific cohorts of particularly vulnerable migrant women who have completed their involvement with Settlement Services and have been in Australia for more than five years. These are former Humanitarian Programme entrants (including Woman at Risk visa holders) and former family stream migrants. See Box 1.1 for more information about these groups. Thinking specifically about these groups, the project had the following aims:

- Understand the current state of migrant women's economic and social participation.

- Document the nature and types of services available to these migrant women.

- Assess the extent to which services/programs are evidence-based or display promising practices.

- Identify best practice and service gaps in relation to services and programs that are funded by the Commonwealth government and provided to these migrant women.

The post-Settlement Services phase is an important time for these women and their families as they negotiate new challenges moving into mainstream services, and continue to build their lives in Australia. Understanding the current state of migrant women's economic and social participation is critical to identifying areas of need for this population.

Some of the challenges faced by migrant women in participating economically and socially in their community are common to those of other Australian women. Barriers to active participation for all women as well as men can include those related to English language proficiency or literacy, having a low level of educational attainment and having mental health or physical health limitations. For migrants these challenges may be more pronounced, with them also having a lack of familiarity with the way the legal system, services, public transport, jobs and training work in Australia. Their experience of these things may have been markedly different, perhaps not existing at all, in their home country. Pre-migration experiences of trauma and violence and existing levels of financial hardship and housing insecurity may add further layers to the challenges faced by some migrant and refugee women, even beyond the initial five years of settlement in Australia. For women also, the caring role associated with family responsibilities is likely to be a priority, perhaps affecting the way they are able to participate socially and economically outside their family. This is of course true for other Australian women but migrant and refugee women (and their families) may have particular cultural beliefs that impact on the roles and responsibilities women feel they should take on inside and outside the home.

This report examines how migrant and refugee women compare to Australian-born women, based on secondary analysis of Australian datasets, with a focus on those factors relevant to economic participation. While social participation is also vital, we are not able to measure this using our key data source, the Australian census.

Understanding how government can help support migrant and refugee women in the community is a significant focus of this research. Broadly, we know that many of the services offered to refugee and migrant women aim to equip them to participate in work or study, and to help link them to others in the community. Most importantly, some address English language proficiency, and are especially targeted at refugees and migrants arriving from non-English speaking countries. Some specific services help migrant women with interpreting and translating needs, difficulties at home, access to housing, counselling, antenatal care, overcoming social isolation by connecting families with more established communities and community engagement opportunities more broadly.

Mainstream service providers also provide some services including housing programs, employment services, legal services, domestic and violence support and support services related to alcohol and other drug use. It is important to recognise, also, that family and friends and the wider community can be an important source of support to migrant women, as to all Australians. Facilitating or strengthening community connections can be an important means of helping address the needs of migrant women in situations that do not require the input of formal services. Such networks may be particularly important for those who are reluctant to use formal services, given past experiences or cultural sensitivities.

The broad research question that was considered in this research was what practical strategies should the government consider to empower migrant and refugee women and that advance and improve migrant and refugee women's safety; economic and social participation; leadership opportunities; and their role in promoting community cohesion? As highlighted in the aims listed above, this research aims to document what services are available, explore to what extent services and programs are evidence-based or display promising practices, and identify some best practice principles and some gaps in service delivery. Specifically, we summarise the findings by answering the following questions.

- What are five good practice principles in service delivery to migrant and refugee women?

- What are five key gaps in service and/or program delivery?

- What are five key priorities for the government to undertake in filling these gaps?

To answer the above questions, we refer to insights from service providers delivering services to migrant and refugee women. The data were sourced from an online survey and from qualitative interviews with service providers in mainstream as well as targeted refugee services. The scope of this research did not extend to capturing the migrant women's perspectives on these issues, and clearly this would be of great interest as an extension to this research. In interpreting the findings based on the reports of service providers, we are also mindful of existing research that is based on those using or requiring services.

We will see that a number of the best-practice principles, key gaps in service and or/program delivery, and key priorities identified through this research are ones that could apply to the delivery of services to different cohorts, not just migrant and refugee women. That does not reduce their relevance to this group, of course. Further, there are some findings from this research that do relate quite specifically to this cohort of women, with some directly relevant to those in the post-settlement period. For migrant women approaching five years after arrival, we also know the service delivery options available to them are changing as they transition to mainstream services. As we discuss later in this report, this transition can be associated with some challenges around culturally and linguistically appropriate service delivery.

The report is structured as follows:

- Section 2 describes an overview of the methodology and research framework underpinning the study and participant recruitment strategies.

- Section 3 explores economic and social participation outcomes for migrant and refugee women and identifies factors associated with employment for recently arrived humanitarian programme migrants.

- Section 4 highlights important findings from the analysis of qualitative and quantitative data collected from service providers delivering services and programs to this cohort.

- Section 5 describes key service gaps and priorities for filling these gaps.

- Section 6 concludes and summarises the key implications for good practice principles in service delivery and key gaps in service and program delivery for prioritisation. Practice implications for organisations delivering services to migrant and refugee women are also outlined.

Box 1.1: Australia's migration programme: Humanitarian programme entrants and family stream migrants

Australia's immigration programme has two components:2

- Humanitarian programme for refugees and others in refugee-like situations; and

- migration programme for skilled and family migrants.

Each component is briefly described here. Further information on Australia's migration programme can be found at the Department of Immigration and Border Protection's website.

The humanitarian programme offers protection for people through Australia's "offshore" and "onshore" resettlement stream. The offshore stream includes two categories of visa for people who are outside of Australia at the time of applying for a visa (visa sub-classes 200, 201, 202, 203 and 204). The onshore stream (866 visa sub-classes covers individuals who arrive in Australia before applying for a humanitarian visa.

In this report, in some cases, analysis results are presented separately for Woman at Risk visa holders (visa sub-class 204). The 204 visa sub-class is for humanitarian programme applicants who live outside of their home country, do not have the protection of a male relative and are in danger of victimisation, harassment or serious abuse because of their gender.3

Family stream migrants are selected based on their family relationship with a sponsor in Australia. There are no skills or language ability tests for these migrants; however, all family stream visa applicants must be sponsored by a close family relative, a partner or a fiancé/ fiancée (depending on the visa type applied for). The family stream migration programme has four main categories: partner, child, parent, or other family visa.4

2.1 Project purpose and background

The project used a mixed-method approach to investigate the experiences of service providers delivering services to migrant and refugee women. The project was conducted over a six-month period (May through November 2016), comprising:

- secondary analyses of available data; and

- primary data collection from service providers and analyses of those data.

These two major components are described in the sections below. To help inform the primary data collection instruments and enhance the research team's understanding of the service delivery landscape, initial consultations with key stakeholders working in migrant and refugee women's services were undertaken in the initial phase of the project. Following these consultations, an Expert Reference Group was formed consisting of seven members from government, universities and service providers. Members of this group informed the research approach and survey content development. Further information on the project's planning, governance and ethics clearance is detailed in Appendix A.

2.2 Secondary data analysis: Migrant women's economic participation

Understanding the current state of migrant women's economic participation is critical to identifying service gaps and areas of best practice in the post-settlement service system. Analysis of the Australian Census and Migrants Integrated Dataset (ACMID) and Building a New Life in Australia (BNLA) datasets was undertaken to identify areas where migrant women trail the wider population in economic participation and in factors that are linked to employment. This research contributes statistical evidence that helps to provide an understanding of the areas of need for this population. Analysis of key economic, education and language proficiency outcomes for humanitarian programme and family stream migrant women was undertaken using these datasets. The datasets and results from these analyses are described in Section 3.

2.3 Primary data collection from service providers

2.3.1 Online survey

One of the primary data collections undertaken for this project was an online survey of service providers, with questions developed to gain insights on the types of services offered to migrant and refugee women who have been in Australia at least five years, and to capture views of challenges, best practice principles and other aspects of this service delivery.

The online survey was primarily quantitative (being largely closed questions) with some open questions seeking text responses. The survey took around 15-20 minutes to complete, was administered during August and September 2016, and was open to participants for around five weeks.5 The online survey data were collected using LimeSurvey software.

AIFS developed participant recruitment materials including an invitation to participate, an information sheet that explained the study background, the voluntary nature of the research, the purpose of the research and a link to participate in the online survey. The participant recruitment material and data collection instruments were granted ethical clearance through the AIFS Ethics Committee. These materials, as well as a copy of the final survey, are available in Appendix B.

Participant recruitment was undertaken via a "snowballing" sampling methodology, whereby appropriate service providers delivering services and programs to Humanitarian Programme and family migrants who had been in Australia for at least five years were identified through relevant DSS networks and approached via email to participate in the survey.6 Information about the project, including a link to the survey, was promoted in the Settlement Council of Australia (SCoA) newsletter, Settlement and Multicultural e-News, and AIFS and Child Family Community Australia (CFCA) newsletters.

In total, 129 participants were surveyed.7 Participants were recruited from a range of services and programs, with the most common service types of participants including accredited language classes (17%), family and domestic violence services (12%), and parent support and education (8%). These services covered ones targeted specifically at migrants or refugees, as well as mainstream services whose clients included migrant and refugee women. Of those service delivery providers who responded to the relevant survey item, roughly equal proportions identified as being from a migrant or refugee background (48%) as not (52%). Table C.1 in Appendix C provides further information about the characteristics of the responding sample.

After the survey was closed to participants, the data was exported for analysis from LimeSurvey to Stata 14.2, a statistical software package. Descriptive analysis techniques were used to describe the results of the survey. Open-text fields were also examined and analysed for key themes. When reporting on these open-text fields in this report, a reference is included that notes the type of service that the respondent was employed in.

Qualitative in-depth interviews

Recruitment for more in-depth qualitative interviews was undertaken by drawing on researchers' networks, recommendations from the Expert Reference Group and respondents who completed the online survey and indicated that they were happy to be invited to participate in a follow-up interview. Analysis of the survey data was undertaken to assist with participant recruitment and ensure that insights were gained from a mix of different service types and locations throughout Australia.

The semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted between 6 September and 11 October 2016 with 13 participants (from 10 organisations) delivering services and programs to migrant and refugee women or from an organisation having an advocacy role on behalf of migrant and refugee women. Their organisations provided a range of programs and services, and had a mix of refugee and migrant clients, from women who had recently settled in Australia to those who had been living in Australia for over 20 years. See Appendix E for information about the qualitative interview participants and their services.

The interview included questions to help inform the broader study aims and research questions. Copies of the interview schedule are included in Appendix D, covering broad themes including:

- information about the participant's service or program;

- collaboration with other service providers (including settlement and mainstream services);

- principles underpinning their program;

- extent to which evaluations have been undertaken of services/programs; and

- key gaps and service priorities for refugee and migrant women.

All interviews were conducted face-to-face or over the telephone, and the average interview length was 45 minutes. The interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. All transcripts were read by the research team, and interview transcripts were de-identified to protect participant confidentiality. Analysis of the transcripts was then undertaken to identify concepts, themes and issues that emerged from the interview data. When citing findings from these participants' interviews, they are referred to by a unique (random) participant number (1 to 13).

2.4 Limitations

One limitation of the methodology was that, due to the tight timelines associated with the project and project scope, the research was only able to gather insights from the perspectives of service providers delivering services and programs to migrant and refugee women. While noting the very useful insights that service providers shared with the research team around best-practice service delivery for these clients, further information from the clients themselves could shed further light on the services available, barriers to access and the issues that are important in migrant women's lives.

Due to the sampling strategy employed, the survey is not a representative sample of all services and programs in Australia being delivered to migrant and refugee women five years after arrival. For this reason, only broad conclusions can be drawn from the results of this data collection. However, the online survey data does provide several insights from the perspectives of service providers involved in the delivery of services around the types of services available, client needs and outcomes and areas of service gaps and priorities.

The 2011 ABS Census data are used to examine the circumstances and experiences of migrants who had been in Australia for five to ten years at that time, including analysing their labour market outcomes. More recent cohorts of migrants may vary in their own attributes (e.g., countries of origin, pre-migration experiences), and will experience different policy settings during and after the initial settlement period. For example, the Australian Government's jobactive program was introduced after the 2011 Census, and so more recent cohorts of migrants may have different employment outcomes to those presented here.

5 The survey was open to participants from 22 August to 26 September 2016.

6 The survey invitation was circulated to DSS Settlement Policy Branch, Family Safety Branch and Family Policy and Programs Branch and targeted to service providers that were in scope. The survey email was also circulated to representatives from the Australian Multicultural Council (AMC), Settlement Services Advisory Council (SSAC), Office for Women within the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Department of Employment, and the Department of Education and Training, who distributed the survey link through their networks.

7 At the close of fieldwork, 139 fully completed interviews had been conducted. After removing those who were out of scope (their organisation had not provided services to migrant women in Australia for at least five years) and including partially completed surveys that had answered at least half the survey content (Question 25 or beyond), the final recruited sample was 129 participants.

3.1 Introduction

To better understand the service needs and potential service gaps for migrant and refugee women, secondary analysis of Australian datasets was undertaken to identify areas where migrant women differ or trail behind the rest of the population. The findings in this section are based on the analysis of two key datasets: the Australian Census and Migrants Integrated Dataset (ACMID; ABS, 2014) and the Building a New Life in Australia (BNLA) study.

ACMID is an Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) dataset that was created using statistical techniques to link records from the DSS Settlement Database to the 2011 Census of Population and Housing. It includes people who have migrated to Australia under a permanent skilled, family or humanitarian stream visa and who arrived in Australia between 1 January 2000 and 9 August 2011.

BNLA is a large-scale longitudinal study of recently arrived humanitarian programme migrants funded by DSS and managed by AIFS. To be eligible for the study, participants had to arrive (or receive a permanent visa) three to six months prior to the first interview (i.e., between May and December 2013). The BNLA study, project background, methodology and participant recruitment are further described in De Maio, Silbert, Jenkinson, and Smart (2014).

Throughout this section of the report, the terms Humanitarian Programme migrants and refugees are used interchangeably and indicate migrants who arrived in Australia on a humanitarian migrant visa. Other migrant women include those with a family visa (partner or family other). Where possible, outcomes are reported separately for each migration pathway.

The analyses of the ACMID data are presented first in sections 3.3 through 3.6. Section 3.2 describes the methods used for these analyses. Section 3.3 provides a demographic profile of migrant women and a comparison with Australian-born women. Section 3.4 examines the labour force participation of migrant women. Section 3.5 then examines how the characteristics of migrant women vary by migrant women's region of birth. The final ACMID analysis in Section 3.6 is an analysis of the economic participation of sub-groups of migrant women within the family other category. Together, these analyses provide a profile of the characteristics of migrant women in the visa streams of interest to this project, focusing on those who have been in Australia for five to then years. This provides some insights on the challenges that may be faced by these women in their capacity for economic and social engagement in Australia, and the challenges that services may face in addressing the needs of these women.

The BNLA analysis is presented in Section 3.7 and describes employment outcomes for Humanitarian Programme migrants who are the focus of the BNLA study. By identifying factors associated with employment among these migrant women, this analysis further extends the ACMID analysis and provides some insights into factors that can assist these migrant women to greater economic participation. While these analyses are based on women who have been in Australia for around three years, these results are likely to indicate which women could face greater challenges in employment outcomes after five years of settlement.

3.2 Analysis of census data: analytical approach

This analysis includes women who migrated to Australia with a family visa (partner or family other) or a humanitarian offshore visa, including Woman at Risk (visa sub-class 204). The scope of the analysis includes women aged 20-70 who arrived in Australia five to ten years before the 2011 Census (all adult population). That is, they arrived between 2001 and 2006.

Analyses were undertaken using TableBuilder (ABS, 2013a). TableBuilder data are confidentialised by randomly adjusting cell values, to avoid the exposure of any identifiable data. These random errors do not impair the value of the table as a whole.8 The ABS advises that small number cells may not be reliable (ABS, 2013a) and so in this report, cells with n < 30 are noted and need to be interpreted with caution.

Most tables present statistics for the four groups of migrant women mentioned above: family partner, family other, Humanitarian Programme and Woman at Risk. Groups were combined into family and humanitarian when numbers were too small to allow for analysis of the four groups separately. The tables exclude respondents with the answers "not applicable", "not stated" or "inadequately stated", unless specified otherwise.

When relevant, the profile of migrant women is compared with the Australian-born female population in the same age group. Some analyses of labour force participation were conducted for a more limited age group to focus on a prime working age of 25-54 years. These comparison data were obtained from the Census of Population and Housing 2011.

Analyses using TableBuilder involves the cross-tabulation of variables but in analysing a particular outcome of interest (e.g., employment participation) does not allow us to take account of all variables that may contribute to this outcome. For example, employment participation is likely to be a factor of age, educational attainment and English language proficiency but in exploring differences by visa category we were unable to take all these factors into account simultaneously. We have presented some detail through building up more complex cross-tabulations but we could not include all key variables. This limitation needs to be taken into account when interpreting the results. The analysis of the BNLA data (in section 3.7) uses multivariate analysis to extend the findings that emerge from the census analysis.

3.3 Characteristics of migrant and Australian-born women

As noted above, here we explore the characteristics of migrant women in the visa streams of family (partner or other) and humanitarian (Woman at Risk and other), who arrived in Australia between 2001 and 2006, and who were in Australia in 2011. This focuses our attention on migrant women in these visa streams who have been in Australia for between five and ten years. Comparisons are also made to the Australian population of women aged 20-70 years at 2011. Box 3.1 summarises the key findings from this section. The characteristics explored here are age, marital status, number of children ever born, educational attainment, English language proficiency, remoteness of region of residence in Australia and socio-economic status of area of residence. More detailed analysis of the location of migrant women is reported in Appendix F (Table F.1). In section 3.5 we look in more detail at characteristics by migrant women's region of birth and in section 3.6 we look in more detail at women in the family "other" migrant stream.

Table 3.1 shows that just under 12,500 women were in Australia in 2011 who arrived between 2001 and 2006 under the four visa categories considered in this analysis. The family partner stream is the largest group, while the Woman at Risk category is the smallest. A higher proportion of migrant women in this analysis arrived in Australia more recently (38% arrived in 2005 or 2006) compared with 28% who arrived between 2000 and 2001.

The age distribution of migrant women differs across groups, which is likely to mean that the needs for services are going to vary across these different groups. For example, younger migrant women are more likely to be in need of assistance in relation to education and reproductive health, while older migrant women may be needing assistance with community engagement, aged care and other forms of health care.

| Year of arrival | Family partner | Family other | Humanitarian | Woman at Risk | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 13,230 | 1,071 | 1,870 | 216 | 16,387 |

| 2002 | 14,351 | 990 | 2,302 | 184 | 17,827 |

| 2003 | 15,474 | 1,371 | 3,074 | 218 | 20,137 |

| 2004 | 14,909 | 2,104 | 3,066 | 172 | 20,251 |

| 2005 | 17,069 | 1,983 | 3,112 | 416 | 22,580 |

| 2006 | 18,857 | 1,898 | 3,179 | 355 | 24,289 |

| Total | 93,890 | 9,417 | 16,603 | 1,561 | 121,471 |

Note: The table population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas.

Source: 2011 ACMID

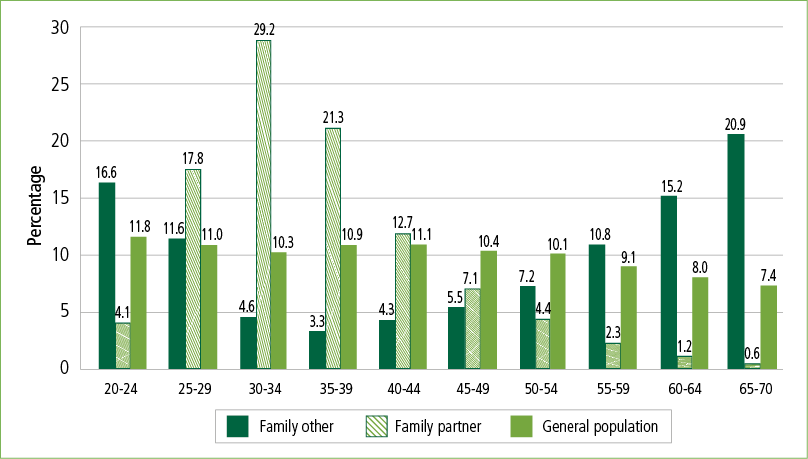

Figure 3.1 shows the age profile of Humanitarian Programme migrant women and the general female population, indicating that Humanitarian Programme migrants are on average younger than women born in Australia. The mean ages for Humanitarian Programme migrant women are 37.3 years for Woman at Risk visa holders and 36.5 for those with other Humanitarian Programme visas. The mean age of Australian-born women (aged 20-70 years) is 42.8. Regarding the family stream Figure 3.2 shows that women in the family other category are older, on average, than those in the family partner group (mean age 47.3 and 36.0 respectively), while women in the family partner category are younger than Australian-born women.

Box 3.1: Key characteristics of in-scope migrant and other Australian women

Women who migrate on family partner, Woman at Risk and other Humanitarian Programme visas are younger than Australian-born women, while those who migrate on family other visas are older on average.

Marital status varies by migration pathway: over one quarter of women on Woman at Risk visas are widows while over three quarters of woman on partner visas are married.

Women on Humanitarian Programme visas, including Woman at Risk, have more children on average than Australian-born women.

Humanitarian Programme migrant women have the lowest levels of education, with the highest proportion of women having never attended school. Women on partner visas have the highest levels of education.

The majority of migrant women live in major cities. The proportion of migrant women in regional and remote areas is lower than for Australian-born women.

More than a third of Humanitarian Programme migrant women live in areas of most disadvantage and lowest advantage. Women in the family stream are somewhat over-represented in areas of disadvantage but have good representation in areas of lesser disadvantage.

Women migrating on partner visas have the highest levels of English proficiency. English proficiency improves over time for the other three groups, but around one in four of these women are not proficient in the English language after being in Australia for ten years.

Figure 3.1: Age distribution of women: Woman at Risk visa holders, other Humanitarian Programme visa holders and women in the Australian-born female population.

Note: The figure population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas; plus Australian-born women aged 20-70 years.

Source: 2011 ACMID and Census of Population and Housing 2011

Figure 3.2: Age distribution of women: family other visa holders, family partner visa holders and women in the Australian-born female population

Note: The figure population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas; plus Australian-born women aged 20-70 years.

Source: 2011 ACMID and Census of Population and Housing 2011.

Table 3.2 shows marital status for migrant women and the Australian-born female population aged 20-70. The marital status and the number of children distributions are, of course, likely to be functions of the age structure of each particular group, which is not taken into account in these tables. As shown in the figures above, there are differences in age structure by migration pathway. As may be expected, women in the family partner group include a higher percentage of married women than the other groups (Table 3.2). Those in the Woman at Risk category have high rates of widowhood.

| Marital status | Family partner (%) | Family other (%) | Humanitarian (%) | Woman at Risk (%) | Australian-born women (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | 76.2 | 49.0 | 55.8 | 27.4 | 51.1 |

| Never married | 11.1 | 27.4 | 23.5 | 32.9 | 32.4 |

| Separated | 4.3 | 1.8 | 8.8 | 7.3 | 3.6 |

| Divorced | 7.3 | 11.6 | 4.3 | 6.7 | 10.3 |

| Widowed | 1.2 | 10.2 | 7.6 | 25.7 | 2.6 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Notes: The table population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas; plus Australian-born women aged 20-70 years. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding and perturbation of data in TableBuilder (see footnote 8).

Source: 2011 ACMID and Census of Population and Housing 2011

Information on the number of children ever born is shown in Table 3.3. Women in the Humanitarian Programme and Woman at Risk categories tend to have had more children than women in the family stream and the Australian-born population. As the Census data refer to the number of children ever been born, it is possible that children may not be living with these women. In the case of migrant women, it is possible that some children may not have migrated to Australia.

| Number of children | Family partner (%) | Family other (%) | Humanitarian (%) | Woman at Risk (%) | Australian-born women (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No children | 30.2 | 32.9 | 23.6 | 30.9 | 30.2 |

| One child | 27.8 | 19.5 | 10.5 | 14.4 | 11.9 |

| Two children | 28.8 | 29.8 | 16.3 | 13.7 | 29.7 |

| Three children | 8.6 | 9.0 | 13.5 | 12.2 | 17.8 |

| Four or more children | 3.1 | 6.2 | 31.3 | 24.0 | 9.5 |

| Not stated | 1.5 | 2.7 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 1.0 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Notes: The table population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas; plus Australian-born women aged 20-70 years. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding and perturbation of data in TableBuilder (see footnote 8).

Source: 2011 ACMID and Census of Population and Housing 2011

Table 3.4 presents the highest level of education achieved for the four migrant groups and the Australian-born population. Educational attainment can be an important variable in measuring likely economic participation, although this is less relevant when thinking about the opportunities for older women, as is also true in relation to Australian women more generally (Baxter & Taylor, 2014). Humanitarian Programme migrants, including those in the Woman at Risk group, have the lowest levels of educational attainment, with over 17% of these women never having attended school. This is compared to less than 1% in the Australian-born female population. Women who migrated as a partner have the highest level of education relative to the other three migrant groups and the Australian-born female population, with over 40% holding a university degree. If these data are analysed for the more limited prime working-age population (25-54 years), a higher proportion have a bachelor degree or higher in each of the categories but the differences are not markedly different from those shown in Table 3.4.

| Highest level of education | Family partner (%) | Family other (%) | Humanitarian (%) | Woman at Risk (%) | Australian-born women (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No school | 1.6 | 3.6 | 16.2 | 17.6 | 0.1 |

| School only | 36.9 | 56.4 | 53.1 | 50.3 | 49.7 |

| Diploma or certificate | 21.5 | 20.3 | 23.6 | 26.2 | 25.0 |

| Bachelor or higher | 40.0 | 19.7 | 7.1 | 5.9 | 25.1 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Notes: The table population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas; plus Australian-born women aged 20-70 years. Percentages may not total exactly to 100.0% due to rounding and perturbation of data in TableBuilder (see footnote 8).

Source: 2011 ACMID and Census of Population and Housing 2011

Figure 3.3: Proficiency in spoken English by year of arrival and migration stream (% who speaks "very well" or "well")

Note: The figure population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas. Calculations exclude those who only speak English.

Source: 2011 ACMID

Proficiency in the English language is beneficial for migrants to be able to participate actively in Australian society. Based on self-reported census data, a high proportion of migrant women are not proficient in spoken English after being in Australia for five to ten years, and this varies by visa category (Figure 3.3). For instance, those arriving on a partner visa have higher levels of English proficiency, and this does not vary with time in Australia. Women arriving on family other visas and on Humanitarian Programme visas have similar levels of proficiency after five years in Australia (in 2011 for those who arrived in 2006), and their proficiency appears to improve over time; 67-68% of women in these groups are proficient in spoken English after being in Australia for ten years.9 However, these data also highlight that between 20% and 37% of women who have been in Australia for ten years are still not proficient in spoken English. This equates to more than 3,700 women across the visa categories considered in this report, for those who arrived in 2001.

Table 3.5 shows that the majority of migrant women in the visa streams in scope for this research, who arrived between 2001 and 2006, live in major cities. More detailed information in Table F.1 (Appendix F) shows that the majority of migrant women live in Sydney and Melbourne, followed by Perth, Adelaide and Brisbane. A comparison by visa category shows that the family partner category has the highest proportion of women living outside of major city areas but this is still the minority, with 87% of these women living in major city areas.

| Remoteness | Family partner (%) | Family other (%) | Humanitarian (%) | Woman at Risk (%) | Australian-born women (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major city areas | 87.4 | 93.5 | 93.7 | 95.3 | 53.9 |

| Inner regional | 7.1 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 28.9 |

| Outer regional | 4.5 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.3† | 13.5 |

| Remote/very remote | 0.9 | 0.1† | 0.1† | 0.0† | 3.4 |

| No usual address | 0.1 | 0.1† | 0.1† | 0.0† | 0.2 |

Notes: The table population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas; plus Australian-born women aged 20-70 years. Percentages may not total exactly to 100.0% due to rounding and perturbation of data in TableBuilder (see footnote 8). † = cell with number < 30.

Source: 2011 ACMID and Census of Population and Housing 2011

To provide insights on the relative disadvantage/advantage of the areas in which migrant women live, we refer to the 2011 SEIFA Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD). This index is calculated by the ABS using 25 variables based on census data including measures of relative disadvantage such as the percentage of people in the area with low education, the percentage of people with low income, the percentage of people in low-skill occupations, as well as measures of relative advantage such as the percentage of people with university education and the percentage of people with high incomes (ABS, 2013b). This information is presented as deciles with Decile 1 being those areas with most disadvantage/least advantage, and Decile 10 being those areas with least disadvantage/most advantage.

Table 3.6 shows that the migrant women in-scope for this research are all more likely to be in the lowest decile compared to the Australian-born population of women aged 20-70 years. This is particularly so for women on Humanitarian Programme or Woman at Risk visas, who are over-represented in the areas of most disadvantage and lack of advantage. More than 30% of these women live in areas that are characterised by the markers of disadvantage as measured in the SEIFA index, and the percentages in higher deciles were low compared to Australian-born women and migrant women arriving on a family visa. Women in the family stream were somewhat over-represented in the areas of most disadvantage and lack of advantage but to a lesser extent (13-16%), with percentages in deciles 5-10 similar to those of Australian-born women aged 20-70 years.

| IRSAD deciles | Family partner (%) | Family other (%) | Humanitarian (%) | Woman at Risk (%) | Australian-born women (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decile 1 | 13.5 | 15.9 | 31.9 | 35.3 | 8.8 |

| Decile 2 | 7.3 | 6.3 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 9.4 |

| Decile 3 | 8.0 | 7.5 | 14.1 | 11.8 | 9.8 |

| Decile 4 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 9.9 |

| Decile 5 | 9.9 | 10.4 | 9.2 | 7.5 | 10.0 |

| Decile 6 | 11.3 | 11.1 | 8.6 | 9.3 | 10.0 |

| Decile 7 | 9.4 | 8.7 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 10.3 |

| Decile 8 | 12.0 | 12.3 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 10.4 |

| Decile 9 | 10.4 | 10.7 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 10.7 |

| Decile 10 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 1.7 | 1.5† | 10.3 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Notes: The table population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas; plus Australian-born women aged 20-70 years. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding and perturbation of data in TableBuilder (see footnote 8). † = cell with number < 30. Those whose areas were not assigned a SEIFA score (presented as "not applicable" in TableBuilder) are included in the total (0.4% of Australian-born women, and < 0.1% of migrant women).

Source: 2011 ACMID and Census of Population and Housing 2011

3.4 Economic engagement

3.4.1 Overview

To look at economic engagement, we explore the labour force participation of migrant women. The definition of employment used in this analysis refers to those who worked in the week prior to census night.11 We have not explored work hours, income, types of jobs or the quality of these jobs.

In this subsection, we start with an overview, exploring economic engagement by visa category and year of arrival. We expand on this in subsection 3.4.2 to further analyse this by women's educational attainment and in subsection 3.4.3 by English language proficiency. Box 3.2 provides an overview of key findings relating to economic engagement for this population reported in the remainder of this section.

Table 3.7 shows the percentage of migrant women employed in 2011 by year of arrival and visa category, with women at risk included in the humanitarian category due to smaller population numbers. With longer time in Australia, there is generally a higher percentage employed.12 However, the employment rates remain relatively low for women who arrived on a humanitarian (including Woman at Risk) visa. The employment rates of migrant women in all categories are lower than for Australian-born females, which was 68% for women aged 20-70 years in 2011.

Box 3.2: Key findings on economic engagement

- The proportion of migrant women in paid employment increases with time in Australia but it is lower than for Australian-born women.

- Even among women with similar levels of education, migrant women have lower levels of employment compared with Australian-born women. The gaps are larger for Humanitarian Programme migrant women than for those who migrated through the family stream.

- In general, women who have ever had fewer children are more likely to be employed.

- Women on Humanitarian Programme visas are less likely to be employed than those in the family stream and Australian-born women, even when comparing women with the same level of education and same number of children.

- Migrant women with higher levels of English proficiency are more likely to be employed. However, when comparing women with similar levels of English proficiency, Humanitarian Programme migrants are less likely to be employed than those in the family stream.

| Visa category | Arrived 2006 (%) | Arrived 2005 (%) | Arrived 2004 (%) | Arrived 2003 (%) | Arrived 2002 (%) | Arrived 2001 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family partner | 54.6 | 55.0 | 56.9 | 56.7 | 57.4 | 59.4 |

| Family other | 36.4 | 37.9 | 37.1 | 46.5 | 47.6 | 56.1 |

| Humanitarian | 22.4 | 27.1 | 29.8 | 31.9 | 32.6 | 37.8 |

| All family and humanitarian | 48.6 | 49.2 | 50.6 | 52.1 | 53.4 | 56.5 |

Note: The table population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas.

Source: 2011 ACMID

Table 3.8 shows labour force status at 2011 by selected visa category for migrant women who arrived in Australia between 2001 and 2006. Consistent with Table 3.7, the lowest employment rates are for women arriving on a humanitarian visa including Women at Risk. The majority of women who arrived in Australia five to ten years before 2011 are not in the labour force in 2011, except for women in the family partner group, who have higher levels of employment participation. Unemployment is most likely for women who were humanitarian migrants, including those arriving on Women at Risk visas, indicating that these women are most likely to be facing barriers to employment, given their classification as unemployed indicates that they do not have a job, have been looking for work and are available to start work should a job opportunity come up.

| Labour force status by visa category | Family partner (%) | Family other (%) | Humanitarian (%) | Woman at Risk (%) | Total migrant (5 years) (%) | Australian-born female population (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employed | 56.5 | 41.7 | 29.5 | 29.8 | 51.4 | 68.4 |

| Unemployed | 5.0 | 5.3 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 5.5 | 2.9 |

| Not in the labour force | 38.5 | 53.0 | 62.4 | 61.3 | 43.1 | 28.6 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Note: The table population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas; plus Australian-born women aged 20-70 years.

Source: 2011 ACMID and Census of Population and Housing 2011

3.4.2 Labour force participation and education

Educational level is a strong predictor of labour force participation (Austen & Seymour, 2006), and we have seen earlier that there is considerable variation in the educational attainment of these migrant women, with a substantial proportion having low educational attainment relative to the Australian population (see Table 3.4). To explore the links between educational attainment and employment for migrant women we focus just on those in prime working age (25-54 years). Table 3.9 presents the labour force participation of migrant women by level of education for each visa group.

Results indicate that among women with similar levels of education, migrant women are less likely to be employed. The exception is among those who never attended school, with Australian-born women having the lowest employment rates, but given that education is compulsory in Australia, this is likely to include those who have been unable to complete schooling due to significant barriers such as having limiting health conditions.

The gap between Australian-born women and migrant women is most apparent in the comparison with women in the Humanitarian Programme visa category, for those with at least some school education. Employment rates of women in the family stream are higher than for Humanitarian Programme migrants but they are still below the employment rates of Australian-born women for those with school education or higher.

| Percentage employed for each visa category and Australian-born women | No school % employed | School only % employed | Diploma or certificate % employed | Bachelor or higher % employed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family partner | 26.9 | 44.3 | 62.4 | 68.0 |

| Family other | 39.3 | 51.0 | 71.0 | 75.8 |

| Humanitarian | 12.4 | 23.7 | 51.4 | 54.7 |

| Australian-born women | 14.7 | 67.2 | 79.5 | 87.3 |

Notes: The table population is 25-54 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas; plus Australian-born women aged 25-54 years. † = cell with number < 30. Australian-born women with no school are likely to comprise those who have been unable to complete schooling due to significant barriers such as having limiting health conditions.

Source: 2011 ACMID and Census of Population and Housing 2011

Table 3.3 in the demographic section showed that women on humanitarian visas tend to have had more children than those in the family stream and the Australian-born female population. The number of children could be a factor that has influenced these women's participation in employment. Here we return to the 20-70 year old population rather than limiting to prime working ages. Similar findings are observed if limited to 25-54 years.

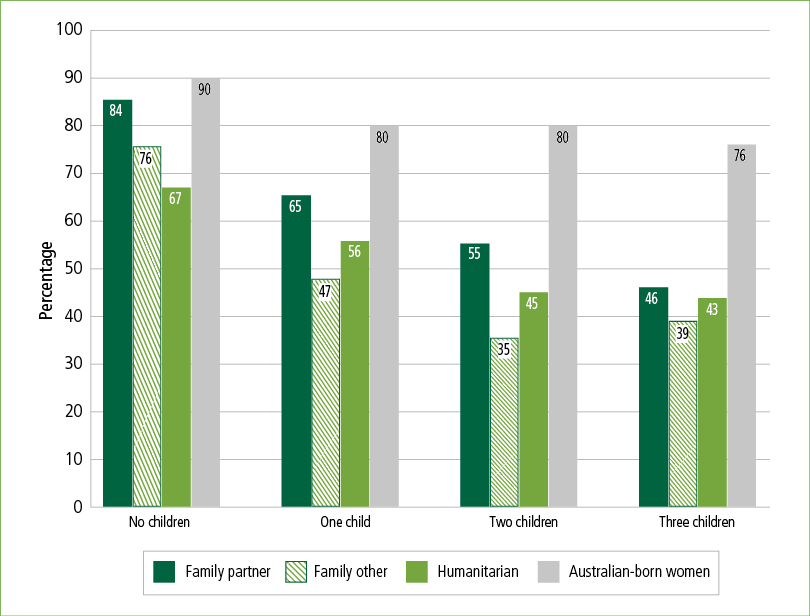

Table 3.10 presents the percentage of women employed by number of children ever born, for each educational level and migration pathway. Due to low numbers, Woman at Risk visa holders and women in other Humanitarian Programme visas have been combined in one group. In general, women who have had more children are less likely to be employed, across visa categories and educational levels. Among women with the same level of education and same number of children, women on Humanitarian Programme visas have lower levels of employment compared with women in the family stream and the Australian population. For example, among women with only school education who have had one child, 46% of those in the family partner group are employed, compared with 25% of Humanitarian Programme migrants and 56% of Australian-born women. Furthermore, among those with a bachelor degree or higher education and no children, 67% of Humanitarian Programme migrant women are employed, compared with 75% of women with family other visas, 84% of women with family partner visas and 90% of Australian-born women. Figure 3.4 and Figure 3.5 illustrate these differences in employment rates by number of children for women with school-only education and women with a bachelor degree or higher education, respectively.

| Level of education and visa category | Four or more children | Three children | Two children | One child | No children | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No school | Family partner | 4.0† | 10.4† | 22.7 | 33.8 | 49.8 |

| Family other | 9.3† | 11.8† | 17.8† | 37.8† | 36.7† | |

| Humanitarian | 8.4 | 11.1 | 15.3† | 14.9† | 17.2 | |

| Australian-born women | 0.0 | 19.8 | 19.0 | 28.0 | 8.0 | |

| School only | Family partner | 24.3 | 25.2 | 33.9 | 46.1 | 65.0 |

| Family other | 16.2 | 28.8 | 29.2 | 31.1 | 49.9 | |

| Humanitarian | 15.3 | 16.7 | 20.5 | 24.9 | 35.9 | |

| Australian-born women | 39.0 | 52.8 | 58.3 | 56.1 | 73.5 | |

| Diploma or certificate | Family partner | 46.6 | 47.0 | 50.9 | 58.2 | 79.7 |

| Family other | 32.3† | 44.3 | 38.5 | 45.4 | 69.3 | |

| Humanitarian | 45.6 | 48.7 | 48.3 | 42.3 | 57.4 | |

| Australian-born women | 63.7 | 70.5 | 72.5 | 70.0 | 86.4 | |

| Bachelor or higher | Family partner | 39.3 | 45.5 | 54.6 | 65.0 | 84.4 |

| Family other | 20.6† | 38.8 | 35.2 | 46.5 | 75.6 | |

| Humanitarian | 35.8 | 42.7 | 44.7 | 56.3 | 67.0 | |

| Australian-born women | 71.4 | 76.2 | 80.4 | 80.0 | 90.0 | |

Notes: The table population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas; plus Australian-born women aged 20-70 years. † = cell with number < 30. Australian-born women with no school are likely to comprise those who have been unable to complete schooling due to significant barriers such as having limiting health conditions.

Source: 2011 ACMID and Census of Population and Housing 2011

These results suggest that women on Humanitarian Programme visas are less likely to be employed, even when educational and child care barriers were not present. This is not surprising, given that these women are likely to have additional factors contributing to their ability to engage economically, related to their pre-migration experiences. Of course, another factor is their level of English language proficiency, which is lower than those arriving on a family partner visa, as shown in Figure 3.3. English language proficiency is examined in the next subsection.

Figure 3.4: Percentage employed by number of children ever born and migration pathway for those whose highest level of education was school only

Notes: The table population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas; plus Australian-born women aged 20-70 years. Excludes those with four or more children.

Source: 2011 ACMID and Census of Population and Housing 2011

Figure 3.5: Percentage employed by number of children ever born and migration pathway for those whose highest level of education was bachelor degree or higher

Notes: The table population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas; plus Australian-born women aged 20-70 years. Excludes those with four or more children.

Source: 2011 ACMID and Census of Population and Housing 2011

3.4.3 Labour force participation and English proficiency

This section examines labour force participation by proficiency in English language for women in the family partner, family other and Humanitarian Programme groups. Table 3.11 shows employment rates for women aged 20-70 years, and also shows the same figures for women aged 25-54 years. When focusing on the 25-54 age group, Humanitarian Programme migrant women have lower levels of participation in the labour force at all levels of English proficiency, relative to family stream migrants. Employment rates are higher for women from English-speaking backgrounds in the three migrant groups.

The patterns (by visa category and English language proficiency) are generally the same for each of these age groups, with higher employment rates when the focus is on prime working ages. However, in the 20-70 years age group, women on family other visas who only speak English have lower employment participation rates than those on Humanitarian visas. We saw in Figure 3.2 that a significant proportion of the family other migrants are aged over 50 years, and in Section 3.6 will see that the family other visa holders are quite diverse, with low employment participation among those whose visa is related to their status as a parent or aged relative.

| Visa category women | Speaks English only % employed | Proficient in spoken English % employed | Not proficient in spoken English % employed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aged 25-54 | |||

| Family partner | 71.3 | 58.0 | 31.3 |

| Family other | 81.9 | 66.5 | 42.1 |

| Humanitarian | 56.7 | 41.1 | 14.4 |

| Aged 20-70 | |||

| Family partner | 69.7 | 57.3 | 30.1 |

| Family other | 45.3 | 53.1 | 24.5 |

| Humanitarian | 51.8 | 38.9 | 12.4 |

Note: The table population is women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas.

Source: 2011 ACMID

| Highest level of education | Visa category women % employed | Speaks English only % employed | Proficient in spoken English % employed | Not proficient in spoken English % employed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bachelor degree or higher | Family partner | 84.6 | 71.8 | 47.1 |

| Family other | 85.4 | 78.9 | 54.2 | |

| Humanitarian | 71.1 | 65.8 | 37.8 | |

| Diploma or certificate | Family partner | 83.9 | 69.3 | 50.2 |

| Family other | 84.6 | 76.7 | 63.2 | |

| Humanitarian | 71.3 | 62.2 | 39.1 | |

| School or no school | Family partner | 75.5 | 56.8 | 39.4 |

| Family other | 83.4 | 69.1 | 52.1 | |

| Humanitarian | 54.0 | 47.2 | 21.4 |

Note: The table population is women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2001-06 on humanitarian or family visas.

Source: 2011 ACMID

Table 3.12 shows that English language proficiency is an important factor associated with employment, and this association is maintained after controlling for educational level. For example, among women with a bachelor degree or higher education, the proportion who are working is significantly higher among those who are proficient in spoken English or speak English only, compared with women who are not proficient in spoken English, in each migration stream. A similar pattern is observed across all levels of education. Table 3.12 also shows that women from a humanitarian background are less likely to be employed, even when they are compared with women with similar levels of education and similar English language proficiency. This difference in the proportion employed is larger among women with lower levels of education.

3.5 Analysis of economic participation by country of birth

It is important to acknowledge that migrants are not a homogeneous group, with one important difference being their country of origin. This section briefly illustrates this, taking a subset of the migrant and refugee women analysed in the sections above, to focus on those who arrived in 2005 or 2006, that is, those who reported having arrived in Australia five years prior to the 2011 Census.

For women in the family stream, the main countries (and associated region) of origin were Egypt (North Africa), Iraq (Middle East), Vietnam and Thailand (South-East Asia), Afghanistan (Central Asia), Ghana (Central and West Africa) and South Africa (Southern and East Africa). Among refugee women the main countries of origin were Sudan (North Africa), Iraq (Middle East), Myanmar (South-East Asia), Afghanistan (Central Asia), Sierra Leone and Liberia (Central and West Africa) and Ethiopia (Southern and East Africa).

Table 3.13 shows that women from Central Asia had low levels of English language proficiency and the highest proportion with no school education. In contrast, 47% of women from Central and West Africa had a post-school qualification and over 55% of them were employed in 2011, which is the highest rates among the regions examined. Notably, 30% of women from Central and West Africa speak English only and few of these women were not proficient in spoken English.

| Measure of economic participation | North Africa (%) | Middle East (%) | Mainland South-East Asia (%) | Central Asia (%) | Central and West Africa (%) | Southern and East Africa (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour force participation | ||||||

| Employed | 22.2 | 12.6 | 31.5 | 6.9 | 55.6 | 23.9 |

| Unemployed | 13.1 | 5.4 | 6.0 | 3.9 | 10.8 | 10.1 |

| Not in the labour force | 64.7 | 82.0 | 62.4 | 89.3 | 33.6 | 66.0 |

| English proficiency | ||||||

| Speaks English only | 2.8 | 0.7† | 1.0† | 0.0† | 30.6 | 1.7† |

| Proficient | 55.5 | 53.4 | 38.9 | 34.4 | 55.6 | 49.6 |

| Not proficient | 41.7 | 46.0 | 60.2 | 65.6 | 13.8 | 48.7 |

| Education | ||||||

| No school | 19.4 | 12.5 | 14.9 | 44.9 | 8.3 | 23.3 |

| School only | 46.1 | 54.6 | 62.1 | 39.5 | 28.2 | 42.8 |

| Diploma or certificate | 13.9 | 16.8 | 14.6 | 6.2 | 44.1 | 17.3 |

| Bachelor or higher | 2.3 | 8.3 | 3.0† | 2.5† | 3.2 | 2.1† |

| Other | 18.3 | 7.7 | 5.4† | 6.9 | 16.3 | 14.5 |

| Approximate n per region | 2,118 | 1,456 | 500 | 940 | 1,153 | 751 |

Notes: The table population is 20-70 year old women in the 2011 Census who arrived in Australia 2005-06 on humanitarian or family visas. Other includes inadequately described and not stated. † = cell with number < 30.

Source: 2011 ACMID

3.6 Analysis of visa type within the family other category

Women who migrate to Australia as a non-partner family member can be broadly classified in three groups: those who came in a carer-related visa category or other family member, those who came in a parent-related visa category and those who came in a child-related visa category.13 They have been included altogether in previous analyses but here we provide some brief analysis of how the characteristics of these migrants varied when examined in more detail.