Parental time with children

Do job characteristics make a difference?

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

Download Research report

Abstract

To contribute to our understanding of how paid work and family time interact, this paper examines how characteristics of parental paid employment are associated with differences in parent-child time. With an increased participation of mothers in paid employment, especially in part-time work, and an increase in non-standard paid work hours, it is important to understand how such factors are related to a loss of time shared between parent and child. The analysis uses the time use diaries of two cohorts of children: the infant cohort (aged 3-19 months old at interview) and the 4-5 year old cohort, collected in the first wave (2004) of the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). For each child, a weekday and weekend diary were completed, resulting in around 6,000 diaries for each cohort. These diaries captured details of the children's activities and who they were with in each 15-minute period. The "who with" data were used to compile measures of parent-child time; that is, times when the mother and/or the father was with the child. Descriptive methods were used to analyse mother-child and father-child time by weekend versus weekday, by time of day and by cohort. Very clear differences emerged. For example, children spent more time with their mother overall and spent more time with parents on the weekend than on weekdays. Multivariate analyses were used to determine whether amounts of parent-child time varied according to job characteristics. Association with parental hours of paid work, evening or night work, weekend work, flexibility of hours, job contract and occupation status were explored. Hours of paid work had the strongest relationships with parent-child time, although the frequency of weekend work also explained some of the variation.

Summary

To contribute to our understanding of how paid work and family time interact, this paper examines how characteristics of parental paid employment are associated with differences in parent-child time. With an increased participation of mothers in paid employment, especially in part-time work, and an increase among all workers in non-standard paid work hours, it is important to understand how such factors are related to a loss of time shared between parent and child.

This paper examines how parental employment characteristics are associated with differences in parent-child time; that is, the time parents and children spend together, focusing on families with young children. The parental employment characteristics taken into account include hours of work, flexibility of hours, frequency of weekend and evening work, type of job contract (permanent, casual, fixed-term, or self-employment), occupational status and the holding of multiple jobs. Inclusion of work hours as well as a range of characteristics allows us to consider how the part-time work (of mothers) and other non-standard work arrangements, such as evening or weekend work, might impact upon family time.

Both children and parents benefit from shared parent-child time, but competing time demands often lead to dissatisfaction with the amount of time parents can spend with their children, and this may be associated with lower parental wellbeing. As an indication that there is some variability according to employment characteristics in how work impacts upon family time, characteristics such as working longer hours, evenings/nights and inflexible hours are generally associated with a greater perception that work has a negative affect on family time. In this paper, we explore whether such associations may be apparent because these and other characteristics result in less parent-child time.

The paper uses data from the first wave (2004) of Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). Both cohorts of children in the study were included - the infant cohort, aged up to 19 months at interview, and the older cohort, aged 4-5 years at interview. As part of LSAC, one of the parents (typically the mother) was asked to enter in a time use diary (TUD) the times during which their child was involved in any of a list of pre-coded activities for each 15-minute interval in a weekday and a weekend day. The TUD also collected, for each time period, details of who was with the child. Better educated and partnered parents were over-represented among the 78% of parents who completed the TUD. The total number of diaries used for the infant cohort was 6,380 (3,247 weekday and 3,133 weekend diaries) and for the 4-5 year cohort was 5,575 (2,799 weekday and 2,776 weekend diaries). This analysis used the TUD to derive measures of total time the child was with their mother or with their father, expressed in minutes per day. These measures are referred to as "mother-time" and "father-time".

From previous studies, the links between parental time in paid employment and family time have been well established, as has the finding that, on average, mothers spend more time with children than do fathers. These findings are clearly linked, since fathers are more likely to be in paid employment than mothers. The analysis of mother-child time and father-child time in this paper also confirms these relationships. At all times across the day, for infants and 4-5 year olds, children were more likely to be with their mother than their father, and therefore spent longer in a day, on average, with their mother. Mothers spent more time with infants than 4-5 year olds, but father-child time differed far less according to the age of the child. Mothers and fathers spent more time with their children on the weekend than on weekdays, which is in part due to the effects of parental employment. The cohort differences in mother-child time can also be explained in part by differences in maternal employment, since mothers are more likely to be employed when their children are older. In addition, for older children, their own involvement in early education appears to limit their availability for shared parent-child time.

A significant factor in explaining parental presence on weekdays is the parents' own work hours. Also, on weekends, the frequency of working weekends is important. Long paid work hours for fathers result in less time spent with children on weekdays and weekends. Rather than making up for lost father-child time on weekends, these fathers may also be working on the weekends, as suggested by somewhat lower father-child time then. For mothers, there is very little relationship between working hours and weekend time with children. While there is no evidence of parents making up lost weekday time with children by spending longer with them on the weekend, fathers who often worked on the weekend spent a little longer with their child during the week.

Consistent with prior research, one hour more of paid employment is not associated with a one-hour decline in time spent with children. In part this is because children spend time in school or early education regardless of parents' employment, and also because even not-employed parents do not spend all their time with children. This analysis shows that some parents work full-time hours and still report being with their child over the day.

After controlling for child and family characteristics, hours worked and frequency of weekend work, other job characteristics have far weaker relationships with parental time spent with children. This suggests that job characteristics such as evening work, employment contract, holding multiple jobs and occupation status are less important in explaining parents' time with children than the key factors of number of paid working hours and weekend work. It may be, however, that some of these indicators are not refined enough to find associations that exist. In particular, the variable capturing evening or night work does not differentiate on whether that work is done at home or not, nor on the exact timing of the work. Each of these aspects of evening or night work may contribute significantly to whether or not evening or night work is associated with differences in parents' time with children.

Jobs with non-standard work arrangements are usually associated with more negative spillover from work to family and access to flexible hours has been linked to lower levels of negative work-to-family spillover. In this paper, comparisons of those with the most flexible jobs to the least flexible jobs (in relation to changeability of start and finish times) found no difference in the total amount of parent-child time. Presumably, while job characteristics such as flexibility of hours and other indicators of non-standard work arrangements are not associated with absolute amounts of time spent with children, they are associated with other factors that are important to parents, such as having the flexibility to fit the desired or required amount of time for children around work commitments.

The most important job characteristics for explaining differences in mother-child and father-child time were hours of employment and the frequency of weekend work. These factors relate to parental availability, and show that time with children is constrained by hours of employment. However, this paper has only explored the existence and total amount of parent-child time. It does not take into account the quality of interactions that occur between parent and child during those shared times. While other job characteristics are not strongly associated with total amounts of parent-child time, they may have an impact upon the nature of this time spent together. This appears to be the case, given the reporting of more negative spillover from work to family for those with particular job characteristics. Access to family-friendly work arrangements are therefore likely to result in positive outcomes for parents and children in ways other than simply increasing the total amount of time they have together.

Parental time with children

To contribute to our understanding of how paid work and family time interact, this paper examines how characteristics of parental paid employment are associated with differences in parent-child time. With an increased participation of mothers in paid employment, especially in part-time work, and an increase in non-standard paid work hours among all workers, it is important to understand whether such factors are related to a loss of time shared between parent and child. This paper examines how parental employment characteristics are associated with differences in parent-child time - that is, the time parents and children spend together - focusing on families with young children.

The motivation for this paper ultimately comes from concern that the wellbeing of families and family members might be adversely affected when parents work in jobs that leave less time to spend with children. The time that parents and children spend together is central to the functioning of families with children. Time together can enhance the wellbeing of family members and develop and build upon their relationships. For children, how much time parents spend with them is related to their intellectual and social development (Cooksey & Fondell, 1996; Crouter & McHale, 2005). For parents, spending time with children is regarded as both enjoyable and beneficial to their children's development (Bianchi, 2000; Daly, 2001; Milkie, Mattingly, Nomaguchi, Bianchi, & Robinson, 2004). Competing time demands, however, often lead to reports of dissatisfaction with the amount of time parents can spend with their children (Milkie et al., 2004; Roxburgh, 2006) and, for mothers in particular, this is associated with lower reported wellbeing (Nomaguchi, Milkie, & Bianchi, 2005) and feelings of guilt (Buttrose & Adams, 2005).

A specific motivation comes from literature on the negative spillover from work to family, which has shown that such spillover varies with different job characteristics (Barnett, 1998; Keene & Reynolds, 2005; Roehling, Jarvis, & Swope, 2005; Strazdins, Clements, Korda, Broom, & D'Souza, 2006). For example, according to other analyses of LSAC data, working longer hours and evenings/nights is generally associated with a greater perception of negative spillover. For mothers, working weekends also results in negative spillover, while for both mothers and fathers, having more flexible work hours reduces this effect (Baxter, Gray, Alexander, Strazdins, & Bittman, 2007). The question from this is whether this variation in negative spillover exists because certain jobs reduce or increase the amount of time parents have with children, or whether such jobs are associated with differences in the ability to manage the work-family balance.

Paid employment can place great demands on parents' time (Milkie et al., 2004). However, within families with young children there is considerable diversity in paid employment arrangements. For example, in 2002, of couple mothers with a child aged under 5, just over half were not employed. Of those who were employed, part-time work was much more common than full-time work (de Vaus, 2004). The majority of fathers with children in this age group were employed and often worked long hours (Baxter et al., 2007). Further, casual work and other jobs with non-standard arrangements are also relatively common among employed parents (see, for example, Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2003; Baxter et al., 2007). These jobs can involve working weekends or outside "standard" working hours, encroaching on what is usually considered family time.

This paper uses children's time use diaries from the first wave (2004) of Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). Both cohorts of children in the study were included - the infant cohort, aged up to 19 months at interview, and the older cohort, aged 4-5 years at interview.

The first aim of this paper is to provide an overview of parental time with children, comparing mothers and fathers, weekends and weekdays, and younger and older children. These comparisons were initially undertaken by examining the times of day that parents and children were together, giving some insight into the rhythms of time involved, and this was followed up by an analysis of the total amount of such time. The second aim is to explore the relationships between parents' time with children and their employment arrangements, in order to examine whether particular types of jobs stand out as having a greater impact upon the time parents spend with their children. In addition to longer work hours, which we expect to decrease parents' time with children, the paper considers a range of other job characteristics, including flexibility of hours, frequency of weekend and evening work, type of job contract (permanent, casual, fixed-term, or self-employment), occupational status and the holding of multiple jobs.

Previous research

A consistent finding in time use research is that mothers spend more time with their children than fathers (Barnes, Bryson, & Smith, 2006; Craig, 2006a; McBride & Mills, 1993; Sayer, Bianchi, & Robinson, 2004), regardless of the employment status of the mother (Zick & Bryant, 1996). As fathers are more likely than mothers to be employed, and more likely to work longer hours, their time with children tends to be greater on weekends than on weekdays (Yeung, Sandberg, Davis-Kean, & Hofferth, 2001).

Maternal employment has an overall impact on the time mothers spend with their children, although a one-hour increase in employment is associated with a much smaller reduction in time spent with children (Bianchi, 2000; Bittman, Craig, & Folbre, 2004; Craig, 2005, 2007; Nock & Kingston, 1988). There are a number of reasons for this. Once children reach school age, the time they spend with parents is reduced by the time they are in school, regardless of the hours of maternal employment. Younger children may also spend time away from parents in other early education programs, particularly preschool (Bianchi, 2000). Therefore, if they are able to schedule their employment to align with school or early education hours, mothers in paid employment may be spending no less time with their children than mothers not in paid employment. Also, even if not employed, mothers are not likely to spend every hour of the day with children, with time also allocated to domestic work, sleep, personal care or recreation. When fitting employment into their day, women may attempt to minimise the loss of child care time, sacrificing time on some of their other activities instead (Bianchi, 2000; Bittman et al., 2004; Craig, 2006a).

More hours of paternal employment generally reduce fathers' time spent with children (Bianchi, 2000; Bryant & Zick, 1996).

The associations between employment and parental time with children are likely to be most evident on the days parents are employed and, since weekday employment is more common than weekend employment (ABS, 2003), most of the effects relate to weekdays rather than weekends (Yeung et al., 2001). Weekday workers may have more weekend time with children than weekend workers, and likewise weekend workers may have more time with children on weekdays if they are able to schedule more time on weekdays to make up for lost weekend time together. However, this assumes that work on weekends is instead of work on weekdays, rather than an extension of full-time work. This may not be the case, and may explain why analyses of associations between parental time with children and weekend/weekday employment are not particularly strong (e.g., Almeida, 2004).

The scheduling or timing of work is also related to parental time with children. Nock and Kingston (1988), for example, reported that parental time with children was related to parents' specific hours of work, with the strongest effect being for after-school time: mothers who work during after-school hours have curtailed shared time with their child. Similarly, Barnes et al. (2006) reported associations between working atypical hours and time spent with children. For mothers and fathers, working early in the morning, in the evening or on Saturdays was associated with less parental time with children. Presser (2004) and Brayfield (1995) also noted the importance of job scheduling in explaining parental time with children. The effects are complex, however. Associations differ for mothers and fathers, and some non-standard work arrangements result in more time spent on some activities with children, and others resulting in less time in other activities. Associations between other job characteristics and parental time with children have been studied less often. Having access to flexible hours does not necessarily affect parents' time with children (Presser, 1989), although it is associated with less negative work-family spillover (Baxter et al., 2007). There is no conclusive evidence on whether being in self-employment or casual work, rather than permanent employment, would make a difference to parental time with children, except that, again, there are likely to be gender differences. Self-employment is a common employment contract for mothers of young children, and while common for fathers also, fathers are less likely to take it up to address family responsibilities (Baines, Wheelock, & Gelder, 2003). Whether occupational group or holding multiple jobs make a difference to parental time with children is unclear - these relationships are explored in this paper.

For couples, there may also be some balancing of work and family time such that the work characteristics of one parent are associated with differences in the other parent's time with children. For example, some have found that fathers spend more time with children when the mother is employed (Bittman, 1999; Sandberg & Hofferth, 2001), while others have not found these relationships (Nock & Kingston, 1988; Pleck & Staines, 1985; Yeung et al., 2001). Mothers' time with children is usually found to have little relationship with fathers' paid work hours (Nock & Kingston, 1988; Pleck & Staines, 1985). While not the main focus of this paper, the analyses incorporate partners' hours worked, in couple families.

Parental time with children may also be related to parental age, family size and family form (couple versus single parent) (Cooksey & Fondell, 1996; Craig, 2006a; Sayer, Gauthier, & Furstenberg, 2004). Parental level of education is often found to be positively related to parents' child care time (Craig, 2006b; Gauthier, Smeeding, & Furstenberg, 2004; Sayer, Gauthier et al., 2004; Yeung et al., 2001; Zick & Bryant, 1996). Possible reasons for this were explored by Sayer, Gauthier et al. (2004), who concluded that for mothers the effect was likely to be related to behavioural differences (education level reflecting different values regarding time spent with children), while for fathers the effect was likely to be related to time constraints (with lower levels of education being associated with employment in paid jobs that impose greater time constraints).

The age of the child is also likely to make a difference to parental time with children. In the context of this analysis, in which parental time with children is compared for infants and 4-5 year olds, we can expect that time spent with the older children would be less because the majority of these children spend part of the week in early education or child care (Baxter et al., 2007; Harrison & Ungerer, 2005), reducing their availability during the day for shared parent-child time. Further, infants may require more direct supervision and more assistance with physical care, which constrain parents to spend more time with the infants. While findings related to other child characteristics are not consistent, other factors that may be associated with parent-child time are the sex and health status of the child (Bryant & Zick, 1996; Cooksey & Fondell, 1996; Yeung et al., 2001).

Relationships between family characteristics (including parental employment) and parental time with children are not expected to be straightforward. In particular, parents may self-select into those jobs that enable them to achieve their desired amount of time with children (Bittman et al., 2004; Crouter & McHale, 2005). Consideration of the effects of employment on mothers' time with children may influence decisions made about maternal employment. Some women will minimise the hours of employment or choose employment that falls within school hours in order to minimise the loss of time with children. That is, decisions about employment and parental time with children might be made jointly. Some analysts (for example, Bryant & Zick, 1996) have designed their research to take parental employment selection effects into account. This approach is necessarily more complicated and requires sufficient information on variables that might predict employment but not necessarily parents' time with children. The wage rate is a key variable in such an analysis, and is not available in this study. The majority of studies do not take selection effects into account, but use employment characteristics to explain variations in parental time with children (for example, Craig, 2007; Nock & Kingston, 1988; Sandberg & Hofferth, 2001; Sayer, Bianchi et al., 2004), and this is the approach taken in this paper.

Much of the existing research on parental time with children is based on adult time use diaries. Australian research has relied heavily on these data in the past (for example, Bittman, 2005; Craig, 2006a, 2006b; Craig, 2007), as has international work (for example, Barnes et al., 2006; Bianchi, 2000; Bryant & Zick, 1996; Nock & Kingston, 1988; Sayer, Gauthier et al., 2004). Exceptions are the analysis of parental time with children by Sandberg and Hofferth (2001), and of fathers' time with children by Yeung et al. (2001), using children's time use diaries from the United States.

Data and method

Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA). Two cohorts of children from across Australia were selected to be part of this study: one infant cohort, aged 3-19 months and the other aged 4-5 years (4 years 3 months to 5 years 7 months) at first interview. The collection for Wave 1 was conducted throughout 2004. The survey collects extensive information about the children, their family and their environment. For a detailed description of the design of LSAC, see Soloff, Lawrence, and Johnstone (2005).

One of the components of LSAC is a time use diary (TUD). The TUD collects details of the activities of the study child over a randomly assigned weekday and weekend day. In the diaries, the day is divided into 96 fifteen-minute time intervals and parents are asked to mark the times during which their child is involved in any of a list of pre-coded activities. These activity details are used to distinguish between children's awake and asleep time. Further details of where the child was in each time period are also collected.

The main focus of this paper is the additional data collected on who was with the child during each 15-minute period. This is defined as who else was in the same room or, if outside, nearby to the child. Parents can mark whether their child was with their mother (including step-mother), father (including step-father), with other adults or relatives, with siblings or other children, or alone. To analyse parental time with children, data on those times in which the child was reported to be with the mother or with the father were used and it was assumed children spent the entire 15-minute period with that parent. These data are referred to as mother-child and father-child time. The data on parental presence do not comprehensively measure the time that parents spend undertaking child care tasks, as parents can be responsible for children or undertake tasks relating to child care while not being in the same room as the children. Neither do these data enable the analyses of what the parent was doing while with the child, so it is not possible to determine whether a parent was actively undertaking child care tasks or largely focused on a different activity.1 One point of difference about these data compared to adults' time use data is that, being from the child's perspective, they capture the total time a parent spent with that one child, which for families with more children is likely to be less than the total time a parent spent with all their children.

For Wave 1 of LSAC, the TUD response rate was, as a percentage of interviewed respondents, 77% for the infant cohort and 78% for the 4-5 year cohort. The TUD sample somewhat over-represents more educated and partnered parents relative to the interviewed sample (see Baxter, 2007, for analysis of the older cohort). The dataset used in this analysis was created from the second release of the LSAC Wave 1 time use diary data (LSAC Project Operations Team, 2006). Children in the infant cohort were aged 9 months on average, while those in the 4-5 year cohort were aged 57 months (4 years, 9 months) on average.

The total number of diaries used for the infant cohort was 6,380 (3,247 weekday and 3,133 weekend diaries) and for the 4-5 year cohort was 5,575 (2,799 weekday and 2,776 weekend diaries). Families were limited to those headed by one or two parents (including step-, foster or adoptive parents) rather than by grandparents or other persons, and other diaries were excluded because of missing data.2 The multivariate analyses were based on slightly smaller numbers because of missing data in the explanatory variables.

The actual parental employment arrangements for the diary day were not known, so it was not possible to determine if or at what times the parents worked on the diary day. Instead, parental employment details were sourced from other Wave 1 data, and therefore referred to the usual work arrangements at the time of these collections of other data.3 Parents who worked full-time hours were fairly likely to have worked on the diary weekday, but those classified as part-time were likely to include a mix of those who worked on this day and those who did not.

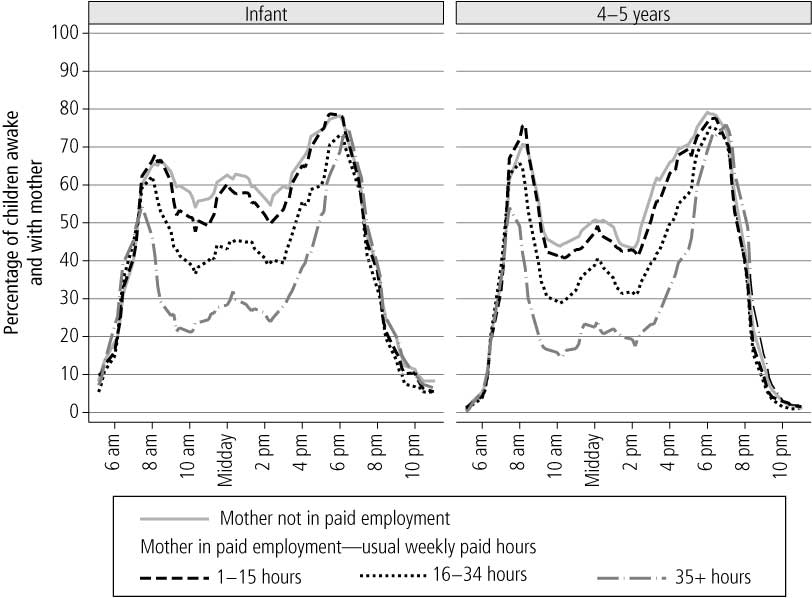

The parent-child time data are first presented graphically (see Figure 1) by time of day, to demonstrate differences between mothers and fathers, weekdays and weekends, and infants and 4-5 year olds. This perspective also demonstrates relationships between hours of employment and parent-child time.

Figure 1: Proportion of children awake and with mother and with father across the day, 5 am to 11 pm

Note: The father-child time is only shown for children with a co-resident father. All children have a co-resident mother.

To identify relationships between family and child characteristics and amount of parent-child time, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was used.4 Sample weights were applied and analyses adjusted for initial sample design by taking into account the clustered nature of the LSAC sample. The analyses controlled for child characteristics (sex, health status and age of child, and number of siblings) and parental characteristics (age, education level). For mothers, family form was included to differentiate between single and couple mothers (there were no single-father families).5 Models were estimated separately for each cohort to enable an examination of how relationships varied according to the age of the child and weekends as opposed to weekdays.

In the multivariate analyses, the dependent variables were the amounts of time (in minutes) that the mother was with the child (mother-child time) and the father with the child (father-child time) while the child was awake. The time that the child was awake was of greatest interest with regard to possible interactions between parent and child, and the potential for improved child outcomes. In the first set of models, all parents were included - employed or not - with hours worked entered in the analyses as categorical variables. Mothers' and fathers' hours were classified into different ranges, given mothers were more likely to work part-time hours and fathers full-time. Mothers' hours were classified as 1-15 hours, 16-24 hours, 25-34 hours and 35 hours or more. Fathers' hours were classified as 1-34 hours, 35-44 hours, 45-54 hours and 55 hours or more.

Given the different ages of children in the infant and 4-5 year cohorts, it is not surprising that rates of maternal paid employment differed across the two groups. In the infant cohort, 40% of mothers were in paid employment, compared to 56% in the 4-5 year old cohort. In the 4-5 year old cohort, mothers worked in paid employment for slightly longer hours - 13% of mothers worked 35 hours or more, compared to 7% for the infant cohort. In both cohorts, most mothers worked part-time hours, with many working fewer than 16 hours (19% in the infant cohort and 20% in the 4-5 year cohort) or 16-24 hours (10% in the infant cohort and 14% in the 4-5 year cohort).

Fathers' paid employment characteristics were similar within each cohort, as most fathers were employed full-time - around 5% were not employed and 5% employed part-time. There was some variation in full-time hours worked: for the infant cohort, 34% usually worked 35-44 hours a week, 28% worked 45-54 hours and 20% worked 55 hours or more; while for the 4-5 year cohort, these figures were 32%, 26% and 22% respectively. For another 8% of the infant cohort and 11% of the 4-5 year cohort, the mother was a single parent.

To investigate relationships with other job characteristics, additional models of parental time with children were estimated for employed parents. In addition to hours worked (by both parents) these models included: job contract (permanent, casual, self-employed, fixed-term or other); flexibility of hours (inflexible = could not change start and finish times, can change hours with approval; flexible hours = can change hours without first seeking approval); frequency of working on weekends (weekly, every 2-3 weeks, every month or less, never); and working after 6 pm or overnight (4 or more days a week/permanent nights, 1-3 days a week, less often, never); as well as three broad occupation groups (managers and professionals; associate professionals, tradespersons, advanced-intermediate clerical, sales and service workers, intermediate production and transport workers; and elementary clerical, sales and service workers, labourers and related workers).

The job characteristics of mothers differed from those of fathers in a number of respects, but for each there were few differences by cohort (Table A1). Fathers were more likely than mothers to be permanent employees. This was the main type of job contract for mothers also, but casual employment was more common for mothers than for fathers. Mothers were more likely to be able to change their start and finish times without seeking prior approval. Fathers more often worked after 6 pm or overnight than mothers and more often worked weekends. Mothers in the infant cohort were more often in the higher status occupation group than either mothers of the older cohort or fathers.

1 See Budig and Folbre (2004) and Craig (2006a) for discussion of the various measures of parental time with children.

2 Some diaries had incomplete information on who was with the child (Baxter, 2007), which meant that for some periods, no indication was given of whether the child was alone or with someone else. Inclusion of data with missing data on who the child was with might result in underestimating parent–child time, so diaries were excluded if data were missing in more than ten time periods (2.5 hours) across the day. This resulted in the exclusion of 791 diaries from the infant cohort and 1,068 from the older cohort. Other diaries were excluded if there were other data quality issues; for example, if there was a large amount of missing activity data during those times parents were present, such that the distinction between awake and asleep time became unreliable (less than 200 excluded from each cohort).

3 Some details were collected in the Wave 1 interview and others in the self-complete component. In 89% of cases, the diary date was in the same month as the initial interview, and in 10% of cases it was in the following month.

4 The Tobit model is often used in analyses of time use data, because of the often-found high proportion of cases with zero amounts reported, which can result in biased OLS coefficients. However, in this analysis, the existence of zero amounts was not a great concern, since most children spent some time with each parent. Most children spent some time with their mother (99% of the infant cohort and 98% of the 4–5 year cohort), with very little differences between weekdays and weekends. The proportions were somewhat lower for fathers—88% of the younger cohort and 84% of the older cohort spent some time during the day with their father, with lower rates on weekdays than weekends. For comparison, Tobit models were also estimated, and marginal effects calculated. For father–child time, small differences emerged between the Tobit marginal effects and OLS coefficients, but the substantive findings were the same. These results are available from the author.

5 When the child did not live with both biological parents, some of the mother–child time or father–child time may have been with a step-parent or a non-resident parent. Because of this, in such families the total parent–child time may have actually been higher than in other families.

Results

Mothers' and fathers' time with children by time of day

In this section, the mother-child and father-child data are examined by time of day, and compared across cohorts and between weekends versus weekdays, to give an initial overview of the nature of parental time with children. Each figure indicates the mother-child and father-child time when the child was awake at that time (that is, if the mother or father was with the child, but the child was asleep, this was not recorded as parent-child time). For example, Figure 1 shows that at around 8 am, about 60% of children were awake and with their mother. Of the remaining 40%, some children would have still been asleep, and others would have been awake but not with their mother.

Looking first at weekdays, in the very early morning and in the evening, parent-child time was similar for mothers and for fathers, and differed little according to the age of the child. But outside these times, children were much more likely to be with their mother than their father. Children's time with parents peaked in the evening, for both mothers and fathers, with a smaller peak in the morning. At the peak evening times, within a 15-minute period, about 75% of children were with their mother (and awake) and about 50% with their father (and awake). Mother-child time differed by age of child, with mothers more likely to be with infants during the daytime (Figure 1).

On weekends, the mother-child and father-child time converged, although children were still more likely to be with their mother than with their father across the day. Here we see that the older children were somewhat more likely to be with either parent during the daytime hours, which will reflect that these data only show awake time with either parent, and infants were more likely to spend some of their day sleeping.

As discussed previously, parent-child time is likely to be restricted by the amount of time parents allocate to the paid labour market. As fathers are more likely than mothers to be in paid employment, there are likely to be greater constraints on their availability, especially on weekdays. Similarly, mothers of older children are more likely to be in paid employment than mothers of younger children, which will affect the extent of their availability.

Figure 2 shows mother-child time on weekdays by usual hours of paid employment. Mothers who usually spent longer hours in paid employment were less likely to be with the child over the day, although being in paid employment for fewer than 16 hours a week was associated with very little difference in mother-child time compared to not being in paid employment. The 4-5 year old children were often not with their mothers between 10 am and 3 pm, even if the mother was not employed, reflecting children's participation in child care or early education programs such as preschool.6

Figure 2: Proportion of children with mother across the day by mother's usual paid work hours for weekdays, 5 am to 11 pm

Even among mothers who worked full-time hours, between 9 am and 3 pm around 20-30% reported to be with their child in any fifteen-minute period. Without more comprehensive information on the parents' time use, which isn't available in these data, it isn't possible to work out exactly how this was managed, but we know from other sources that some employed women do their work from home, perhaps enabling them to work and provide care at the same time (Baxter & Gray, 2008). Other mothers are likely to be working shifts such that their full-time hours do not actually correspond with the "usual" full-time schedule. For others, the day on which the TUD was recorded may not have actually been a usual work day; for example, they or their child may have been sick or on holiday.

There is no evidence here that employed mothers, or those working longer hours, make up time with their children by spending longer with them in the morning or evening.

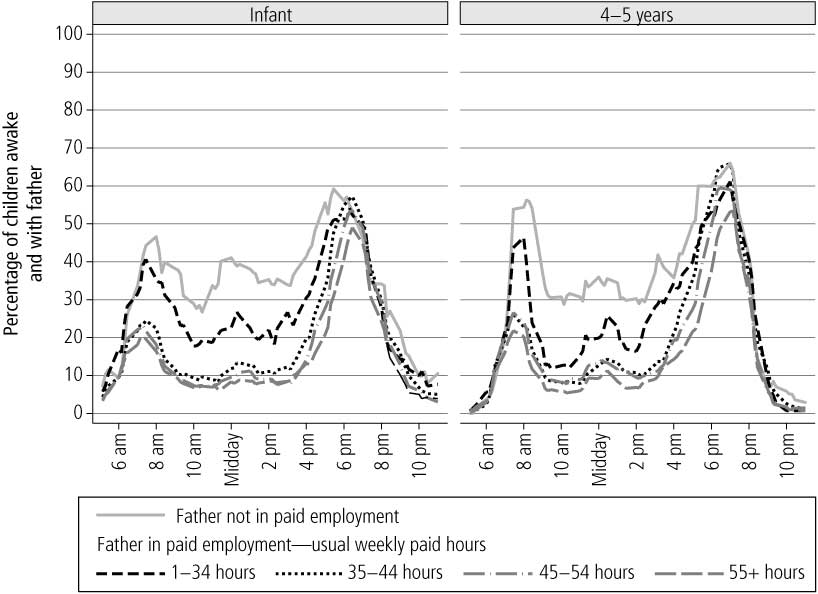

Figure 3 shows that fathers' presence was also associated with their paid work hours, although differences were quite small by hours worked for those employed full-time - the majority of fathers. For these fathers, few were with their child during the daytime. Differences by hours were a little more apparent early in the afternoon and evening, as those working short full-time hours may have come home from work sooner than those working longer hours.

The groups that stand out are the fathers who were not employed or who were in part-time work - they spent more time with their children than fathers in full-time employment. However, these fathers were the minority. Also, comparing back to the mothers' graph (Figure 2), these fathers were still not as likely to be with the children as the not-employed or part-time-employed mothers.

Figure 3: Proportion of children with father across the day by father's usual paid work hours for weekdays, 5 am to 11 pm

Note: The father-child time is only shown for children living with a co-resident father.

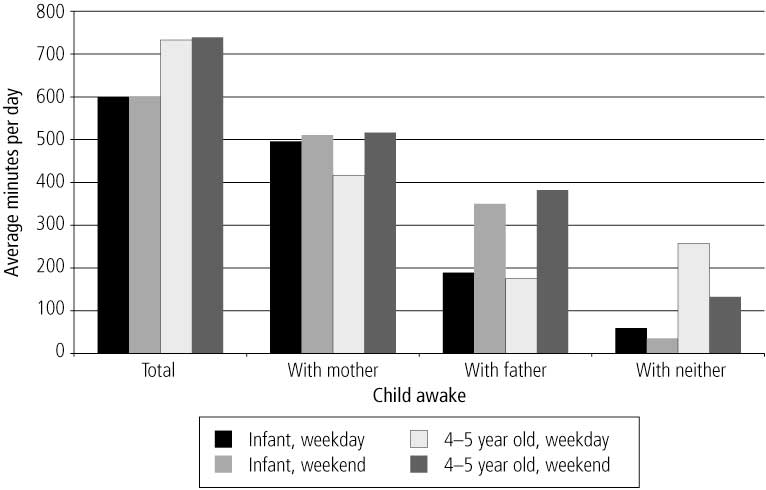

Total mother-child and father-child time

In aggregating these time use data across cohorts and weekdays, it is first worth noting one difference between the child cohorts that directly captures differences in the children's ages: older children spent somewhat more time awake compared to the infants (Figure 4 and Table A2). Cohort differences in parental time with children should be interpreted with this in mind. The mother-child time was highest for weekends, at an average of 511 minutes for infants, and practically the same time (516 minutes) for 4-5 year olds. For weekdays, the infant mother-child time was only slightly lower than this, at 496 minutes. The 4-5 year weekday mother-child time was lower, at 416 minutes. Father-child time was also greatest for weekends, and was higher for the older cohort (350 minutes for infants and 382 minutes for 4-5 year olds). Weekday father-child time was slightly higher for the younger cohort at 189 minutes, compared to 175 minutes for the 4-5 year olds.

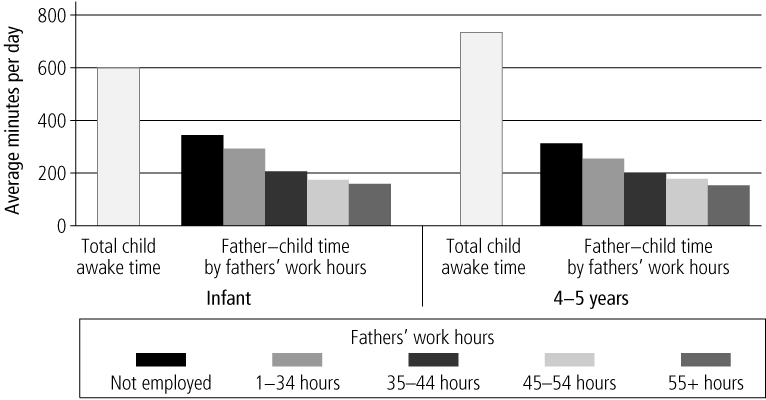

Figure 4: Child awake, mother-child and father-child time, weekdays and weekend

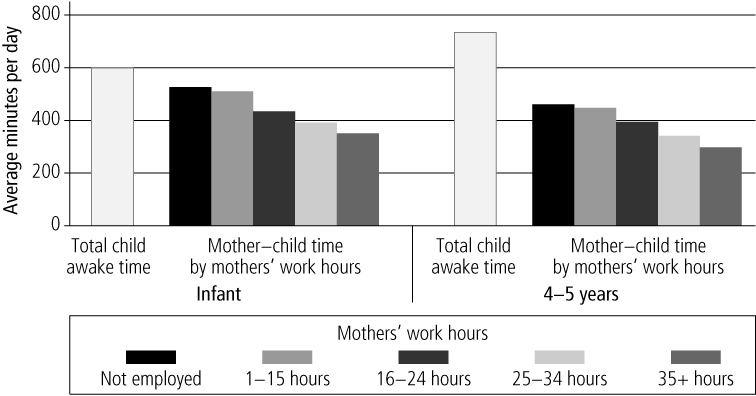

Again, summarising these data for weekdays only by hours of paid work, Figure 5 shows how mother-child time varied with mothers' paid work hours. The total child awake time has been included for comparison. For infants with a not-employed mother, there was not much of a difference between the total awake time and the total mother-child time (when awake infants were almost always with their mother). In families with a not-employed mother but an older child (a 4-5 year old), the gap was larger, again showing that this gap was more likely related to the child's absence from the mother than the mother's absence from the child.

Figure 5: Weekday mother-child time, by mothers' paid work hours, and total time awake

More hours of maternal work did reduce time with children in both age groups. Those with the lowest mother-child time were mothers working full-time hours, although they still spent on average, about 300 minutes (5 hours) with their 4-5 year old in a day, and slightly more with infants.

For fathers, there was a more substantial gap between the child's awake time and the total father-child time, even for not-employed fathers or fathers working part-time hours. Increases in hours worked were associated with declines in father-child time. Among the full-time employed fathers, there was around 50 minutes per day difference, when comparing those working the more standard 35-44 hours to those working 55 hours or more.

It is worth noting from these results for mothers and fathers, that a one hour increase in employment did not equate to a one hour reduction in time with children. For example, compare a mother of a 4-5 year old who was not employed to a mother in paid employment for 35 hours or more per week. It is necessary to make assumptions in order to do these calculations: assume a woman working full-time hours spreads those hours over 5 days, with usual weekday work hours of 7 hours 30 minutes, or 450 minutes. The difference in mother-child time for these mothers was 163 minutes (based on data in Figure 6). Clearly, there is a very large difference between the 450 minutes additional paid work hours and the 163 minutes lower mother-child time. For every additional minute worked, about one-third of this translates into lost mother-child time. While very approximate, given the assumptions made, the results are consistent with other time use analyses, which have shown that a one-hour increase in employment does not translate into an hour lost with children. How this is managed clearly is of interest, especially considering Figure 2, in which it is evident that children of full-time employed mothers spent no longer with their mother in the morning or evening than other children, but were often with their mother during the day. Similar analyses of father-child time shows that fathers also do not lose an hour of father-child time for every hour worked.

Figure 6: Weekday father-child time, by fathers' paid work hours, and total time awake

Multivariate results

These data on mother-child and father-child time were then analysed using OLS to determine what employment characteristics were associated with more or less time spent with children, after controlling for other child or family characteristics. This was first done for all parents (Table 1) and then for parents in employment (Table 2). This section presents these results, focusing on usual hours of paid work from Table 1 and other characteristics from Table 2. While there are some interesting relationships between parent-child time and the various control factors, these are not discussed, with the exception of parental education.

The figures above show that hours of paid employment had associations with parent-child time on weekdays. This is also evident in the multivariate results. The fewer hours of paid work by the mother, the greater the mother-child time. Maternal paid work hours reduced mother-child time more for infants than for 4-5 year olds. This makes sense, as discussed above, since for the older cohort, mother-child time is already lower because of children's participation in early education. Also, the fewer hours worked by the father, the greater the father-child time. Among full-time employed fathers, the differences in time with children were significant, but not large.

According to Table 1, father-child weekend time was lower when fathers spent longer in paid employment, suggesting that these long work hours spilled over into weekends. (In fact, according to data on frequency of weekend work, around half the fathers working 55 hours or more worked on weekends every week, and another quarter did so every two to three weeks). Mothers' work hours had a lesser impact on mother-child weekend time, but mothers were less likely than fathers to be in full-time paid employment, reducing the likelihood of them working the long hours that result in weekend work. (Some parents working shorter hours also worked on weekends, but the proportions were low relative to the fathers in long hours of paid work.)

| Mother-child time | Father-child time | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekday | Weekend | Weekday | Weekend | |||||

| Infant | 4-5 years | Infant | 4-5 years | Infant | 4-5 years | Infant | 4-5 years | |

| Constant | 385*** | 347*** | 552*** | 584*** | 287*** | 266*** | 445*** | 462*** |

| Mother's paid employment (ref. = 35 hours or more) | ||||||||

| Not employed | 170*** | 164*** | 9 | 3 | -56*** | -50*** | -30 | -2 |

| 1-15 hours | 153*** | 143*** | 1 | -21 | -54*** | -37** | -20 | 10 |

| 16-24 hours | 81*** | 101*** | -29 | -16 | -57*** | -24 | -33 | 19 |

| 25-34 hours | 38 | 39* | -40* | -12 | -31 | -49*** | -46* | 24 |

| Father's paid employment (ref. = 35-44 hours) | ||||||||

| Not employed | -24 | -3 | 25 | 21 | 131*** | 120*** | 3 | 24 |

| 1-34 hours | -2 | 2 | 22 | 30 | 79*** | 48** | 9 | -19 |

| 45-54 hours | -4 | -5 | -9 | 9 | -31*** | -22* | -23** | -22* |

| 55 hours or more | 10 | 27** | -4 | 27* | -46*** | -44*** | -58*** | -49*** |

| Parent's education (ref. = incomplete secondary only) | ||||||||

| Complete secondary | -9 | 2 | -9 | 9 | -10 | 14 | 20* | 30* |

| Degree or higher | -14 | -16 | -12 | 0 | -16* | -8 | 42*** | 51*** |

| Single parent | 17 | 2 | 2 | -3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Age of parent (centred) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Sex of child (girl) | -1 | 3 | -8 | 9 | -15* | -10 | -13 | -29** |

| Age of child (months-centred) | -2 | -5** | 2 | 0 | -2 | -1 | 3* | -1 |

| Child has poor/fair health | 7 | -3 | -16 | -57 | 0 | 35 | -13 | -78* |

| Number of siblings (ref. = no siblings) | ||||||||

| 1 | -7 | -19 | -20** | -50*** | -19** | -11 | -45*** | -15 |

| 2 or more | -4 | -29* | -8 | -68*** | -9 | -25 | -48*** | -43* |

| R-square | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Sample size | 3,210 | 2,778 | 3,097 | 2,756 | 3,003 | 2,523 | 2,910 | 2,514 |

Notes: Continuous variables centred as follows: age of child at 9 months for infants and 57 months for 4-5 year olds; age of parents at 35 years for mothers and 38 years for fathers. Parent characteristics are those of mother for mother time and of father for father time. A control for missing data was also included. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

There is some evidence that the time one parent shared with their child varied according to the other parent's work hours. In the 4-5 year cohort, mother-child time on weekdays and weekends was higher in families in which the father worked 55 hours or more. However, on weekdays, the stronger relationship is between mothers' paid work hours and father-child time. In both cohorts, fathers spent the most time with the child when the mother worked full-time hours.

Turning to the results for parents in paid employment (Table 2), once other job characteristics are controlled for, parental hours of employment remain a significant variable in explaining time with children. One relationship that changes is between fathers working longer hours and their weekend time with children - once other job characteristics are included, this effect is smaller, although significant, for infants, but non-significant for the 4-5 year olds. For the older cohort of children, long hours in themselves did not affect fathers' weekend time with children. This was related to the inclusion of indicators capturing the frequency of weekend work, since, as discussed above, long work hours tend to mean an increased tendency to work on weekends.

| Employed mothers, mother-child time | Employed fathers, father-child time | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekday | Weekend | Weekday | Weekend | |||||

| Infant | 4-5 years | Infant | 4-5 years | Infant | 4-5 years | Infant | 4-5 years | |

| Constant | 373*** | 352*** | 564*** | 621*** | 244*** | 251*** | 470*** | 553*** |

| Mother's employment (ref. = 35 hours or more) | ||||||||

| Not employed | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | -38* | -49*** | -26 | -7 |

| 1-15 hours | 136*** | 133*** | -12 | -19 | -41** | -39** | -11 | 8 |

| 16-24 hours | 78*** | 96*** | -32* | -15 | -46** | -24 | -33 | 12 |

| 25-34 hours | 32 | 34 | -37* | -12 | -16 | -47** | -41 | 5 |

| Father's employment (ref. = 35-44 hours) | ||||||||

| Not employed | -66* | -9 | 17 | 51 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 1-34 hours | 15 | -8 | 27 | 56* | 70*** | 46* | 24 | 6 |

| 45-54 hours | 12 | 4 | 3 | 23 | -38*** | -30*** | -11 | -3 |

| 55 hours or more | 28* | 35* | 14 | 36* | -60*** | -58*** | -25* | 1 |

| Frequency of working weekends (ref. = never) | ||||||||

| Weekly | 38* | 21 | -36* | -46** | 14 | 32** | -66*** | -92*** |

| Every 2-3 weeks | 32 | 13 | 21 | -38* | 16 | 18 | -40*** | -58*** |

| Monthly or less often | -10 | -7 | 23 | -17 | -1 | -4 | -4 | -15 |

| Flexibility of hours (ref. = can change times - works flexible hours) | ||||||||

| Can change hours with approval | -26* | 4 | -26* | -28* | -6 | -6 | -19* | 3 |

| Cannot vary hours | -5 | 25 | -12 | -22 | 7 | 7 | -4 | -18 |

| Missing a | 1 | -4 | -17 | -27 | -10 | -9 | -22 | -51** |

| Multiple jobs | -12 | 13 | -25 | -9 | 18 | 5 | 9 | -13 |

| Job contract (ref. = permanent or ongoing) | ||||||||

| Self-employed | 8 | 20 | -4 | -11 | 17* | 2 | -5 | -36** |

| Casual | 16 | -17 | 19 | -10 | 3 | -15 | -24 | -36 |

| Fixed term or other | -3 | 3 | 15 | -41* | -4 | -9 | 30 | -7 |

| Frequency of working after 6 pm or overnight (ref. = never) | ||||||||

| 4-7 days a week/permanent nights | 9 | -42* | -14 | 21 | 13 | -2 | -14 | -22 |

| 1-3 days a week | -3 | -5 | -32** | 7 | 7 | 18 | -13 | -2 |

| Less often | 20 | -46** | -13 | -2 | 19* | 11 | 2 | 0 |

| Occupation group (ref. = managers & professionals) | ||||||||

| Associate professionals, tradespersons, advanced-intermediate clerical, sales & service workers, intermediate production & transport workers | -5 | -4 | -15 | -9 | 12 | 1 | 9 | -38*** |

| Elementary clerical, sales & service workers; labourers & related workers | -8 | -28 | -6 | -8 | 27 | 11 | -9 | -44 |

| Parent's education (ref. = incomplete secondary only) | ||||||||

| Complete secondary | -21 | -2 | 1 | 19 | -6 | 14 | 17 | 14 |

| Degree or higher | -21 | -28 | -9 | 3 | -4 | -3 | 33** | 4 |

| R-square | 0.181 | 0.149 | 0.113 | 0.106 | 0.077 | 0.071 | 0.094 | 0.103 |

| Sample size | 1,305 | 1,613 | 1,284 | 1,584 | 2,828 | 2,379 | 2,762 | 2,371 |

Notes: Time with mother includes employed mothers only and time with father includes employed fathers only. Employed fathers include those with not-employed wives, and employed mothers include those with not-employed husbands. Parent characteristics are those of mother for mother time and of father for father time. Models also include controls for family form, age of parent and child, sex of child, number of siblings, health of child and missing data. a Non-respondents to the self-completion questionnaire, where this information is collected. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Mothers' and fathers' times with infants and children on the weekend are related to the frequency of weekend work. As might be expected, mothers and fathers who worked more often on the weekend spent less weekend time with their children. This is particularly evident for fathers. Weekend work also had a significant association with father-child weekday time - those who frequently (weekly or every 2-3 weeks) worked weekends spent more time with their children during the week, making up for some of the time lost on weekends. There is some evidence of this also for mothers who frequently worked weekends and their time with infants.

There are surprisingly few other significant associations between parent-child time and employment characteristics. Further, the findings are not always consistent across cohorts. For example, for the variable that captures frequency of evening or night work, in addition to there being different associations for parents of infants and parents of 4-5 year olds, frequent evening or night work is not associated with differences in amounts of parent-child time, but the associations are evident for those with less frequent evening work. Few relationships are evident for occupation group, for type of job contract and being a multiple job holder.

The flexibility of hours has weak relationships with mothers' and fathers' time with children. There are no significant differences between those with the most flexible and the least flexible work hours. In some cases, parents' time with children was greater if working flexible hours rather than requiring approval to change start and finish times. This affected mothers' time with infants on weekends and weekdays, mothers' time with 4-5 year olds on weekends and fathers' weekend time with infants.

The effects of parental education warrant some discussion. Neither mothers' nor fathers' education have a significant relationship with mother- or father-child time on weekdays. However, fathers with more education spent more time with their children on weekends. The effect is greatest in the first analyses (Table 1), before the inclusion of job characteristic variables. For 4-5 year olds, fathers with a degree or higher spent 51 minutes more per day with their child than a father with incomplete secondary education, all else being equal. The effect is smaller for infants, although there was a significant difference of 42 minutes between the lowest and highest education groups. After controlling for job characteristics (Table 2), fathers' education continued to have a significant association with weekend time for infants, but there was less of a gradient according to level of education, and the effect disappeared for 4-5 year olds. This suggests the education effect shown in Table 1 probably captures some effects of differences in employment characteristics. That is, lower educated fathers may work in jobs that are more time constrained. However, it seems plausible that the education effect that remains after controlling for job characteristics may be related to different attitudes towards parenting and sharing of child care tasks.

6 Other TUD data support this. On weekdays, children in the 4–5 year cohort spent, on average, 165 minutes a day away from their parents and in child care or other organised activities. Even among 4–5 year olds with a not-employed mother, this figure was 138 minutes. For the younger cohort, children spent an average of 21 minutes away from parents and in child care or organised activities.

Discussion and conclusion

Whether viewed as the proportion of children who are with their mother or father across the day, or as the average number of minutes of mother-child and father-child time, some patterns in parental time with children are evident. At all times, for infants and 4-5 year olds, children were more likely to be with their mother than their father, and therefore spent longer, on average, with their mother in a day. Mothers spent more time with infants than 4-5 year olds, but father-child time differed far less according to the age of the child. Mothers and fathers spent more time with their children on the weekend than on weekdays, which is in part due to the effects of parental employment. The cohort differences in mother-child time can also be explained in part by differences in maternal employment, since mothers are more likely to be employed when their children are older. In addition, for older children, their own involvement in early education appears to limit their availability for shared parent-child time.

A significant factor in explaining parental presence on weekdays is the parents' own work hours. By examining the parent-child data by time of day, the temporal nature of the relationship between work hours and this parent-child time is clear. Also, on weekends, the frequency of working weekends is important. These factors relate to parental availability, and show that time with children is constrained by hours of employment.

Long paid work hours for fathers result in less time with children on weekdays and weekends. Rather than making up for lost father-child time on weekends, these fathers may also be working on the weekend, as suggested by somewhat lower father-child time then. For mothers, there is very little relationship between working hours and weekend time with children. While there is no evidence of parents making up lost weekday time with children by spending longer with them on the weekend, fathers who often worked on the weekend spent a little longer with their child during the week.

After controlling for child and family characteristics, hours worked and frequency of weekend work, other job characteristics have far weaker relationships with parental time spent with children. This suggests that job characteristics such as evening work, employment contract, holding multiple jobs and occupation status are less important in explaining parents' time with children than the key factors of number of paid working hours and weekend work. It may be, however, that some of these indicators are not refined enough to find associations that exist. In particular, the variable capturing evening or night work does not differentiate on whether that work is done at home or not, nor on the exact timing of the work. Each of these aspects of evening or night work may contribute significantly to whether or not evening or night work is associated with differences in parents' time with children.

Jobs with non-standard work arrangements are usually associated with more negative spillover from work to family (Alexander & Baxter, 2005; Strazdins et al., 2006). Further, access to flexible hours has been linked to lower levels of negative work-to-family spillover (Hill, Hawkins, & Ferris, 2001). In this paper, comparisons of those with the most flexible jobs to the least flexible jobs (in relation to changeability of start and finish times) found no difference in the total amount of parent-child time. Presumably, while job characteristics such as flexibility of hours, and other indicators of non-standard work arrangements, are not associated with absolute amounts of time with children, they are associated with other factors that are important to parents, such as having the flexibility to fit the desired or required amount of time for children around work commitments.

There is some balancing of employment arrangements and caring of children that occurs between couples, with fathers spending somewhat more time with children on weekdays in families in which the mother works the longest hours. The contribution to parent-child time by fathers, however, does not entirely make up for the amount of parent-child time lost through the employment of mothers, so fathers make up some of the difference, but not all. Also, this seems to be most prevalent in families where the mother works full-time hours. While such families are a minority when children are young, it appears that these families make the greater adjustments to facilitate these work arrangements. Similarly, when fathers work longer full-time hours, mother-child time is higher, also suggesting a balancing of care according to the demands of work commitments. While this paper only examines total parent-child time, and not the activities being undertaken in this time, it does suggest that fathers may take up some of the child care tasks in those families where there is a need to do so, and that mothers' time with children is affected by the long work hours of fathers. To fully understand these relationships, the parents' time use would need to be examined, which is not available in this dataset.

Questions remain unanswered in relation to how job characteristics and parental time with children are associated. In particular, this analysis shows that one hour of paid employment is not associated with a one-hour decline in time spent with children, for either mothers or fathers. One contributing factor seems to be that some parents work full-time hours and still report to be with their child over the day. A clearer understanding of how this is managed would be valuable.

In the analysis presented in this paper, no attempt has been made to determine whether parents have selected into certain jobs in order to maintain their time with their children. It is quite possible that this occurs, especially for mothers who may seek jobs for those times children are in someone else's care; for example, at preschool for older children. Likewise, some families may rely on a father being more available to help with child care if the mother is to work full-time, and the mother being more available if the father is to work longer full-time hours.

The quantity of parent-child time, as used in this analysis, is just one measure of parental input to children's lives. Clearly, it does not tell the entire story, with variations in the quality of that time also likely to matter (Dermott & Dermott, 2005; Zubrick, Silburn, & Prior, 2005), as could be indicated through the nature of the parenting relationship or the degree of interaction between parent and child. In recognition of this, another forthcoming paper by Baxter (2009) that uses these data explores the nature of the parent-child time by analysing the types of activities children are doing while parents are present.

Further work is possible with these data, especially considering the longitudinal nature of and wealth of data in LSAC relating to parenting and child outcomes.

Appendix

| Mother | Father | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant (Per cent) | 4-5 years (Per cent) | Infant (Per cent) | 4-5 years (Per cent) | |

| Job contract | ||||

| Self-employed | 27 | 25 | 22 | 26 |

| Permanent employee | 49 | 50 | 69 | 68 |

| Casual employee | 19 | 19 | 5 | 4 |

| Contract or other | 5 | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| Flexibility of start-finish times | ||||

| Can vary hours, works flexible hours | 52 | 52 | 43 | 44 |

| Can vary hours with approval | 26 | 25 | 30 | 28 |

| Cannot vary start-finish times | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Missing (non-response) | 7 | 7 | 13 | 13 |

| Frequency of working after 6 pm or overnight | ||||

| 4 or more days a week, or permanent nights | 8 | 9 | 21 | 23 |

| 1-3 days a week | 29 | 27 | 27 | 28 |

| Less often | 13 | 15 | 22 | 20 |

| Never | 49 | 49 | 30 | 29 |

| Frequency of weekend work | ||||

| Weekly | 21 | 20 | 26 | 24 |

| Every 2-3 weeks | 15 | 15 | 23 | 22 |

| Every month or less | 17 | 19 | 25 | 27 |

| Never | 46 | 46 | 26 | 28 |

| Has more than one job | 10 | 13 | 10 | 11 |

| Occupation group | ||||

| Managers & professionals | 40 | 36 | 36 | 37 |

| Associate professionals, tradespersons, advanced-intermediate clerical, sales & service workers, intermediate production & transport workers | 48 | 51 | 55 | 54 |

| Elementary clerical, sales & service workers; labourers & related workers | 12 | 13 | 9 | 9 |

| Weekday | Weekend | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant | Infant | |||||||

| Total | With mother | With father | With neither | Total | With mother | With father | With neither | |

| Awake | 599 | 496 | 189 | 59 | 600 | 511 | 350 | 35 |

| Sleeping | 811 | 327 | 182 | 412 | 812 | 322 | 224 | 423 |

| Total | 1,410 | 823 | 370 | 470 | 1,412 | 834 | 575 | 458 |

| 4-5 years | ||||||||

| Awake | 733 | 416 | 175 | 257 | 739 | 516 | 382 | 132 |

| Sleeping | 665 | 238 | 149 | 347 | 672 | 245 | 179 | 352 |

| Total | 1,399 | 654 | 324 | 603 | 1,411 | 760 | 561 | 484 |

Lists of tables and figures

List of tables

- Table 1 Mother-child and father-child time (minutes per day), children's awake times, OLS regression coefficients

- Table 2 Parents in paid employment: mother-child and father-child awake time (minutes per day), OLS regression coefficients

List of figures

- Figure 1 Proportion of children awake and with mother and with father across the day, 5 am to 11 pm

- Figure 2 Proportion of children with mother across the day by mother's usual paid work hours for weekdays, 5 am to 11 pm

- Figure 3 Proportion of children with father across the day by father's usual paid work hours for weekdays, 5 am to 11 pm

- Figure 4 Child awake, mother-child and father-child time, weekdays and weekends

- Figure 5 Weekday mother-child time, by mothers' paid work hours, and total time awake

- Figure 6 Weekday father-child time, by fathers' paid work hours, and total time awake

Appendix tables

- Table A1 Descriptive statistics, employed parents

- Table A2 Who was with the child weekdays and weekends, by whether child was asleep or awake

References

- Alexander, M., & Baxter, J. (2005). Impacts of work on family life among partnered parents of young children. Family Matters, 72, 18-25.

- Almeida, D. M. (2004). Using daily diaries to assess temporal friction between work and family. In A. C. Crouter & A. Boot (Eds.), Work-family challenges for low income families and their children (pp. 127-136). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2003). Working arrangements, Australia (Cat. No. 6342.0). Canberra: ABS.

- Baines, S., Wheelock, J., & Gelder, U. (2003). Riding the roller coaster: Family life and self-employment. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Barnes, M., Bryson, C., & Smith, R. (2006). Working atypical hours: What happens to "family life"? London: National Centre for Social Research.

- Barnett, R. C. (1998). Toward a review and reconceptualization of the work/family literature. Genetic, Social & General Psychology Monographs, 124(2), 125-182.

- Baxter, J. (2007). Children's time use in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children: Data quality and analytical issues in the 4-year cohort (LSAC Technical Paper No. 4). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Baxter, J. (2009). An exploration of the timing and nature of parental time with 4-5 year olds using Australian children's time use data. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Baxter, J., & Gray, M. (2008). Work and family responsibilities through life. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Baxter, J., Gray, M., Alexander, M., Strazdins, L., & Bittman, M. (2007). Mothers and fathers with young children: Paid employment, caring and wellbeing (Social Policy Research Paper No. 30). Canberra: Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

- Bianchi, S. M. (2000). Maternal employment and time with children: Dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography, 37(4), 401-414.

- Bittman, M. (1999). Parenthood without penalty: Time use and public policy in Australia and Finland. Feminist Economics, 5(3), 27-42.

- Bittman, M. (2005). Sunday working and family time. Labour & Industry, 16(1), 59.

- Bittman, M., Craig, L., & Folbre, N. (2004). Packaging care: What happens when children receive nonparental care? In N. Folbre & M. Bittman (Eds.), Family time: The social organization of care (pp. 133-151). London: Routledge.

- Brayfield, A. (1995). Juggling jobs and kids: The impact of employment schedules on fathers' caring for children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 57, 321-332.

- Bryant, W. K., & Zick, C. D. (1996). An examination of parent-child shared time. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58(1), 227-237.

- Budig, M., & Folbre, N. (2004). Activity, proximity, or responsibility? Measuring parental childcare time. In N. Folbre & M. Bittman (Eds.), Family time: The social organization of care (pp. 51-68). London: Routledge.

- Buttrose, I., & Adams, P. (2005). Motherguilt: Australian women reveal their true feelings about motherhood. Camberwell, Vic.: Viking.

- Cooksey, E. C., & Fondell, M. M. (1996). Spending time with his kids: Effects of family structure on fathers' and children's lives. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58(3), 693-707.

- Craig, L. (2005). How do they find the time? A time-diary analysis of how working parents preserve their time with children (Discussion Paper No. 136). Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales.

- Craig, L. (2006a). Does father care mean fathers share? A comparison of how mothers and fathers in intact families spend time with children. Gender and Society, 20(2), 259-281.

- Craig, L. (2006b). Parental education, time in paid work and time with children: An Australian time-diary analysis. British Journal of Sociology, 57(4), 553-575.

- Craig, L. (2007). How employed mothers in Australia find time for both market work and childcare. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28(1), 89-104.

- Crouter, A. C., & McHale, S. M. (2005). Work, family, and children's time: Implications for youth. In S. M. Bianchi, L. M. Casper, & R. B. King (Eds.), Work, family, health, and well-being (pp. 49-66). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Daly, K. J. (2001). Deconstructing family time: From ideology to lived experience. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 283.

- de Vaus, D. A. (2004). Diversity and change in Australian families: Statistical profiles. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Dermott, E., & Dermott, E. (2005). Time and labour: Fathers' perceptions of employment and childcare. Sociological Review, 53(s2), 89-103.

- Gauthier, A. H., Smeeding, T. M., & Furstenberg, F. F., Jr. (2004). Are parents investing less time in children? Trends in selected industrialized countries. Population and Development Review, 30(4), 647-671.

- Harrison, L., & Ungerer, J. (2005). What can the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children tells us about infants' and 4 to 5 year olds' experiences of early childhood education and care. Family Matters, 72, 26-35.

- Hill, J. E., Hawkins, A. J., & Ferris, M. (2001). Finding an extra day a week: The positive influence of perceived job flexibility on work and family life balance. Family Relations, 50(1), 49-58.

- Keene, J. R., & Reynolds, J. R. (2005). The job costs of family demands: Gender differences in negative family-to-work spillover. Journal of Family Issues, 26(3), 275-299.

- LSAC Project Operations Team. (2006). The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children data users guide, Version 1.7. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- McBride, B. A., & Mills, G. (1993). A comparison of mother and father involvement with their preschool age children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 8, 457-477.

- Milkie, M. A., Mattingly, M. J., Nomaguchi, K. M., Bianchi, S. M., & Robinson, J. P. (2004). The time squeeze: Parental statuses and feelings about time with children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(3), 739.

- Nock, S. L., & Kingston, P. W. (1988). Time with children: The impact of couples' work-time commitments. Social Forces, 67(1), 59-85.

- Nomaguchi, K. M., Milkie, M. A., & Bianchi, S. M. (2005). Time strains and psychological well-being: Do dual-earner mothers and fathers differ? Journal of Family Issues, 26(6), 756.

- Pleck, J., & Staines, G. (1985). Work schedules and family life in two-earner couples. Journal of Family Issues, 6(1), 61-82.

- Presser, H. B. (1989). Can we make time for children? The economy, work schedules, and child care. Demography, 26(4), 523-544.

- Presser, H. B. (2004). Employment in a 24/7 economy: Challenges for the family. In A. C. Crouter & A. Boot (Eds.), Work-family challenges for low income families and their children (pp. 83-105). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Roehling, P. V., Jarvis, L. H., & Swope, H. E. (2005). Variations in negative work-family spillover among white, black, and hispanic American men and women: Does ethnicity matter? Journal of Family Issues, 26(6), 840-865.

- Roxburgh, S. (2006). The distribution and predictors of perceived family time pressures among married men and women in the paid labor force. Journal of Family Issues, 27(4), 529-553.

- Sandberg, J. F., & Hofferth, S. L. (2001). Changes in children's time with parents: United States, 1981-1997. Demography, 38(3), 423-436.

- Sayer, L. C., Bianchi, S. M., & Robinson, J. P. (2004). Are parents investing less in children? Trends in mothers' and fathers' time with children. American Journal of Sociology, 110(1), 1-43.

- Sayer, L. C., Gauthier, A. H., & Furstenberg, F. F., Jr. (2004). Educational differences in parents' time with children: Cross-national variations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(5), 1152.

- Soloff, C., Lawrence, D., & Johnstone, R. (2005). Sample design (LSAC Technical Paper No. 1). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Strazdins, L., Clements, M., Korda, R. J., Broom, D. H., & D'Souza, R. M. (2006). Unsociable work? Nonstandard work schedules, family relationships and children's well-being. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 68, 394-410.

- Yeung, W. J., Sandberg, J. F., Davis-Kean, P. E., & Hofferth, S. L. (2001). Children's time with fathers in intact families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(1), 136-154.

- Zick, C. D., & Bryant, W. K. (1996). A new look at parents' time spent in child care: Primary and secondary time use. Social Science Research, 25(3), 260-280.

- Zubrick, S., Silburn, S., & Prior, M. R. (2005). Resources and contexts for child development: Implications for children and society. In S. Richardson & M. R. Prior (Eds.), No time to lose: The well-being of Australia's children (pp. 161-200). Carlton: Melbourne University Press.

Jennifer Baxter is a Research Fellow at the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS), where she works largely on employment issues as they relate to families with children. Since starting at AIFS, Jennifer has made a significant contribution to a number of important reports, including the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) Social Policy Research Paper No. 30, Mothers and Fathers with Young Children: Paid Employment, Caring and Wellbeing (Baxter, Gray, Alexander, Strazdins, and Bittman, 2007) and AIFS' submission to the Productivity Commission Parental Leave Inquiry (2008). She has also contributed several Family Matters articles and had work published in other journals. Her research interests include maternal employment following childbearing, child care use, job characteristics and work-family spillover, breastfeeding, children's time use and parental time with children. She has made extensive use of data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) to explore these areas of research.

Jennifer was awarded a PhD in the Demography and Sociology Program of the ANU in 2005. Her work experience includes more than fifteen years in the public sector, having worked in a number of statistical and research positions in government departments.

The author would like to thank reviewers Lyn Craig (Social Policy Research Centre, University of NSW) and Duncan Ironmonger (University of Melbourne), as well as Matthew Gray and Alan Hayes (Australian Institute of Family Studies), for providing valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper. Any remaining errors or omissions remain my own.

This Research Paper makes use of data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, is conducted in partnership between the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, the Australian Institute of Family Studies and the Australian Bureau of Statistics, with advice provided by a consortium of leading researchers.

Baxter, J. (2010). Parental time with children: Do job characteristics make a difference? (Research Paper No. 44). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

978-1-921414-11-4