Patterns and precursors of adolescent antisocial behaviour

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

December 2002

Suzanne Vassallo, Diana Smart

Download Research report

Foreword

Understanding the processes by which children develop into well adjusted, law abiding citizens is crucial if we are to succeed in building safer communities. Effective crime prevention programs must be guided by sound, empirically based evidence. However, this information often takes time to collect and evidence that is available mostly relates to offending behaviour in other countries, and hence has uncertain applicability to the Victorian context.

The research presented in this First Report, Patterns and Precursors of Adolescent Antisocial Behaviour, is the product of a collaboration between the Australian Institute of Family Studies and Crime Prevention Victoria. The report is the culmination of six months work and describes findings from the Australian Temperament Project, a large longitudinal study which has followed a representative sample of Victorian children and their families from infancy to adolescence. It focuses on the nature and prevalence of adolescent antisocial behaviour in this sample, and examines precursors of this behaviour from infancy onwards.

This First Report makes a significant contribution to our understanding of the factors that influence the development of antisocial behaviour in Victorian adolescents. This research is particularly relevant to the Victorian Government's Safer Streets and Homes Strategy. It provides guidance on the nature and timing of intervention efforts aimed at redirecting children from problematic developmental pathways to pathways with more positive outcomes.

The collaborative partnership will produce a Second Report which will include an examination of factors which may protect against the development of adolescent antisocial behaviour; an analysis of the differences between adolescents who engage in violent versus non-violent antisocial acts; and an examination of the influence of neighbourhood context on engagement in adolescent antisocial behaviour.

Crime prevention research needs to be able to be translated into action. The results from this study will enable new ways of thinking about prevention and early intervention with the aim of reducing the development of antisocial behaviour. Translating research findings into practical solutions is challenging, but a substantial first step has been taken with this report.

André Haermeyer

Victorian Minister for Police and Emergency Services

Download publication

Preface

This report on the patterns and pathways to antisocial and criminal behaviours among Australian adolescents represents the first publication from the collaborative project between the Australian Institute of Family Studies and Crime Prevention Victoria.

The setting for the project is the longitudinal community study, the Australian Temperament Project (now in its twentieth year), which is itself a collaboration between researchers from the Institute, the Royal Children’s Hospital, and the University of Melbourne.

The study involves a representative sample of more than 2400 children and families living in urban and rural areas of Victoria. With its focus on children’s psychosocial development from infancy to adolescence, the study provides a rare and valuable opportunity to explore the development of teenage antisocial behaviour in an Australian context.

The origins of many problems in adolescence and adulthood can be traced back to early childhood. This report makes a substantial contribution to our understanding of how and why antisocial behaviours develop in childhood and adolescence, and identifies opportunities for assisting vulnerable youngsters to move onto more positive pathways. In doing so, it adds to the evidence base for policy and practice regarding Australian children and their families.

I commend Patterns and Precursors of Adolescent Antisocial Behaviour and am confident it will be of interest and value to the research community, to policy makers, and to parents, teachers and professionals who work with children and families. In particular, it is hoped that the report, in addressing current policy concerns, will facilitate government and community efforts to ensure the very best outcomes for all our children and their families.

David I. Stanton

Director

Australian Institute of Family Studies

Executive summary

Adolescence is a crucial time for the emergence of antisocial and criminal behaviour which, for some, persists into adulthood; at considerable cost to individuals, families and the wider community. Much research has been devoted to the identification of risk factors associated with the occurrence of criminal and antisocial behaviour, with the aim of preventing such problems. However, much of the research has been cross-sectional or covered restricted age spans, conducted in other countries, employed disadvantaged samples, and focused on males. Its applicability to the Victorian and Australian context is uncertain.

Few Australian studies have examined the precursors of and pathways to antisocial behaviour from the earliest years of life. The present study, a collaborative project between Crime Prevention Victoria (Victorian Department of Justice), and the Australian Institute of Family Studies, uses data from the Australian Temperament Project to describe patterns and precursors of antisocial behaviour among a representative community sample of Victorian adolescents.

In this report a considerable amount of statistical data is presented, so that those who are interested can examine them in detail. However, at key points throughout the report summaries of the results are provided so that those who wish can bypass the statistical details.

Australian Temperament Project

The Australian Temperament Project (ATP) is a large scale, longitudinal study that has, to date, followed Victorian children from infancy to 17-18 years of age. The initial sample comprised 2443 infants (aged 4-8 months) and their parents, who were representative of the Victorian population at that time (1983). In total, twelve waves of data have been collected, via annual or biennial mail surveys. Using age-appropriate measures, data have been collected on aspects such as the child’s temperament, behavioural and emotional adjustment, academic progress, health, social skills, peer and family relationships, as well as family functioning, parenting practices and family socio- demographic background. Parents, teachers and the children themselves have acted as informants at various stages during the project. During the last three data collection waves in 1996, 1998 and 2000, when participants were aged 13-14, 15-16 and 17-18 years, adolescents answered questions regarding their engagement in antisocial acts.

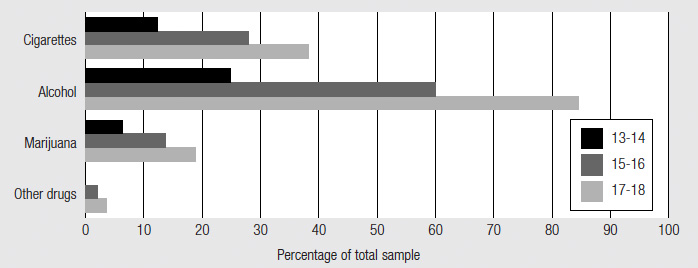

Frequency of antisocial acts across the adolescent years

Antisocial behaviour was quite common among ATP participants over the period 13-14 to 17-18 years. One of the most common types of antisocial behaviour was property offences, with approximately 10-20 per cent of participants engaging in acts such as theft or vandalism. Cigarette and alcohol use were also common (39 per cent and 85 per cent respectively, at 17-18 years); however, fewer participants had used marijuana (increasing from 6 per cent at 13-14 years to 19 per cent at 17-18 years) and very few (less than 4 per cent) had used “hard drugs”. Authority conflict and violent antisocial acts were much less common, with the exceptions of skipping school (a high of 43 per cent at 17-18 years) and involvement in physical fights (a high of 34 per cent at 13-14 years). About one in ten participants had been in contact with the police for offending, but only a very small number had been charged (2-3 per cent), appeared in court (about 1 per cent), or been convicted of a crime (less than 1 per cent).

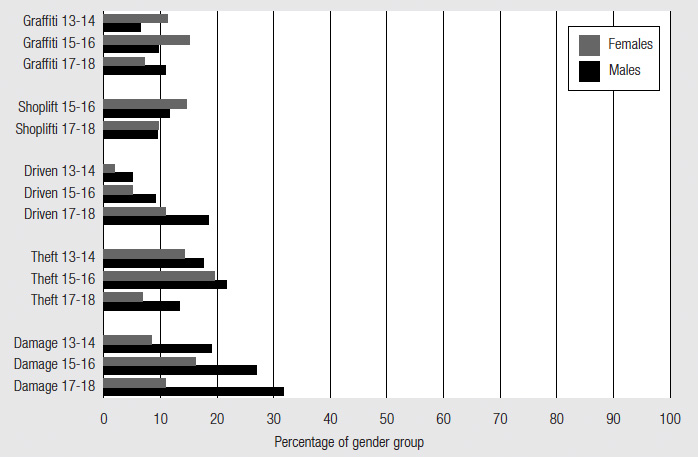

Frequency of antisocial acts among males and females

Cigarette use, alcohol use, and skipping school were the most common antisocial behaviours for both males and females. A higher proportion of males than females had engaged in violent and drug-related antisocial acts such as physical fighting (for example, 52 per cent of males at 13-14 years compared with 15 per cent females); been suspended/expelled from school (ranging from 6 to 9 per cent males compared with 2 to 4 per cent of females); committed property offences such as driving a car without permission (5-19 per cent males; 2-11 per cent females) and damaging property (19-32 per cent males; 8-11 per cent females); and been in contact with the criminal justice system (for example,19 per cent males and 6-8 per cent females had been in contact with the police for offending). Females, on the other hand, were more likely than males to have engaged in graffiti during early adolescence (11 per cent females compared with 7 per cent males at 13-14 years).

Patterns of antisocial behaviour over time

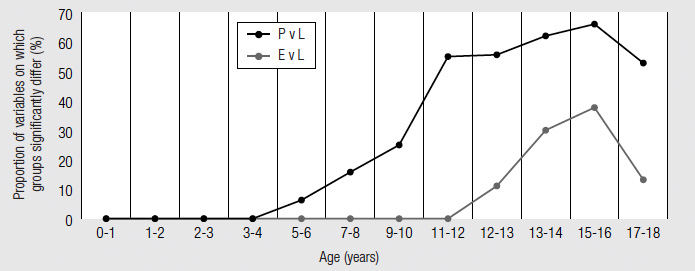

Different patterns of antisocial behaviour were identified among participants over 13-14, 15- 16 and 17-18 years of age, leading to the formation of three groups. These were: 844 “Low/non antisocial” (those who exhibited no or low levels of antisocial behaviour at all timepoints); 88 “Experimental” (those who exhibited high antisocial behaviour – three or more different antisocial acts in the past year – at only one timepoint during early-to-mid adolescence); and 131 “Persistent” (those who reported high antisocial behaviour – three or more different antisocial acts in the past year – at two or more timepoints, including the last data collection wave at 17-18 years). A further 103 were not included, as they did not fit the criteria for the three groups.

Predictors of antisocial behaviour across time

No significant differences were found between the two antisocial groups and the low/non antisocial group during infancy and early childhood. The first group differences emerged at the beginning of primary school (5-6 years). Clear and consistent differences between the persistent and low/non antisocial groups were observed from this time on. During mid childhood, the persistent antisocial group had higher levels of acting out, aggressive and hyperactive behaviour problems, and were more inclined to display volatility and to experience difficulties in maintaining attention than the low/non antisocial group. In late childhood, the persistent antisocial group continued to display problematic behaviour, and in addition were less cooperative, had poorer self-control, had poorer relationships with parents, and were more likely to have friends who engaged in antisocial behaviour.

The experimental and low/non antisocial groups did not differ significantly until early adolescence. During adolescence, the experimental group resembled the persistent group on many domains, although generally was less dysfunctional. The two antisocial groups were significantly more problematic than the low/non antisocial group on a wide range of domains, including school progress, attraction to risk taking, coping styles, parent-child relationships, and parenting style. Towards the end of adolescence, this pattern of differences appeared to change, with the experimental group becoming more similar to the low/non antisocial group.

Predictors of antisocial behaviour across domains of functioning

Group differences typically centred on temperamental characteristics such as negativity, volatility and low persistence, as well as aggressive, acting out and hyperactive behaviour problems, to the disadvantage of the antisocial groups. Powerful group differences were also observed in the domains of social competence, association with antisocial peers, school adjustment during adolescence, coping styles and involvement in risk-taking activities. Less powerful but significant group differences were also observed in family structural characteristics, parenting practices, and family relationships.

Gender differences in the predictors of antisocial behaviour

The effects of gender on the prediction of antisocial behaviour were investigated by (1) controlling for the effects of gender, and (2) conducting separate analyses for males and females. These analyses revealed a similar pattern of results to those described above, however, group differences during the early to mid primary school years were generally fewer, when sex-specific analyses were conducted.

Group differences over time

Key findings

1. Some degree of antisocial behaviour is “normal” in adolescence

Consistent with previous research, the findings of this study suggest that some degree of antisocial behaviour is common among adolescents. However, there are distinct patterns both in the timing, the frequency, and the nature of the antisocial behaviours, which need to be taken into consideration by prevention strategies.

2. Early interventions to divert children from pathways to persistent antisocial behaviour are most appropriate during the primary school years for the majority of young people

The current findings suggest that parents, teachers, clinicians and policy makers should focus on the early primary school years as a critical time for intervention in attempting to prevent the development of persistent antisocial behaviour. In this study, group differences first emerged at the age of 5 to 6 years (the commencement of primary school for most participants), suggesting that this period represents an early point in developmental pathways for the majority of children.

It is widely recognised that interventions during the earliest years of life are critical for the prevention of numerous emotional and behavioural problems (for example, hyperactivity, attention-regulation problems). Hence, more broad-based interventions (for example, home visiting programs), during infancy and early childhood, which aim to prevent the development of problems before they emerge, may also prove beneficial. Infants and young children whose sociodemographic and familial characteristics place them at increased risk of later developing antisocial behaviour would particularly benefit from such preventative efforts. Nevertheless, the current results suggest that when targeting the pathways to persistent antisocial behaviour, the focus should be on the early primary school years as a crucial period to intervene.

3. Persistent antisocial youth exhibit a clear profile

Individuals who went on to engage in persistent antisocial behaviour during adolescence were consistently reported to be more aggressive, more disinhibited, and more temperamentally reactive from mid-childhood onwards than individuals who later engaged in little or no antisocial behaviour. Furthermore, from late childhood, this group exhibited lower social competence, and associated more frequently with antisocial peers. Given the consistency of these findings, it may be possible to identify children who are at risk of developing persistent antisocial behaviour at quite a young age, for whom targeted interventions may be beneficial.

4. Interventions targeting experimental antisocial behaviour need to be multi-faceted and focus on the early secondary school years

Individuals who engaged in transitory antisocial behaviour during mid adolescence had shown clear signs of dysfunction from the early adolescent years, following the transition to secondary school. While they showed no signs of adjustment difficulties and were similar to the low/non antisocial group during childhood, in the early adolescent years they became more “difficult” temperamentally, more aggressive, began to experience difficulties at home and at school, and were likely to have formed friendships with youth who also engaged in antisocial behaviour. Due to the wide range of difficulties exhibited by individuals displaying experimental antisocial behaviour, interventions aimed at preventing this type of behaviour should be multi- faceted and targeted at the early secondary school years. It will be important to follow the trajectory of this group into young adulthood, to ascertain if their problems were truly transitory.

5. Precursors of antisocial behaviour are similar for males and females

When differences between antisocial groups were examined separately for males and females, differences generally emerged at the same times and in the same domains for both sexes. These findings suggest that interventions aimed at preventing the development of antisocial behaviour may be used equally well with males and females.

6. Peer relationships and their influence

The existence of friendships with other antisocial youth was one of the most powerful risk factors for both persistent and experimental antisocial behaviour identified by this study. Such friendships were evident from as early as 11-12 years of age, and prior to the onset of antisocial behaviour. Other aspects of peer relationships also appeared important. The low/non antisocial group members were more attached to their peers (had greater trust and communication), and more frequently interacted with peers in a structured setting (for example, while playing sport). The two antisocial groups, on the other hand, appeared to spend more time with peers, but their time together was more likely to be unstructured.

7. The role of family environment

There were few significant differences between the three groups on socio-demographic characteristics such as family socioeconomic status, parental education, occupational, and ethnic background, and number of children in the family. However, within-family processes, (for example, the parent-child relationship, the degree of warmth and conflict in this relationship, alienation from parents, family cohesion, and marital conflict and breakdown) were important contributors to group differences. Parenting style was also important, with parents of antisocial youth more prone to use lower supervision, less warmth and more harsh discipline. In general, family environment factors were less powerful in impact than individual child characteristics.

8. The importance of school adjustment

Clear group differences in school adjustment and school bonding were evident during the secondary school years. Both the persistent and experimental groups were observed to have more difficulties adjusting to school, and to exhibit lower levels of attachment to school, than those in the low/non antisocial group. These findings suggest that the manner in which an individual adapts to the school environment, the way in which the school accommodates the child’s individual characteristics and needs, and adolescents’ attitudes about schooling, are important predictors of adolescent antisocial behaviour.

Summary

In summary, this First Report has documented substantial group differences between adolescents who engage in high levels of antisocial behaviour and those who do not, which are evident from the early primary school years on, and increase in strength and diversity over time. The most powerful group differences emerge in intra-individual characteristics such as temperament, behaviour problems, social skills, levels of risk-taking behaviour and coping skills, and in the domains of school adjustment and peer relationships. Significant group differences in aspects of the family environment were also found. These findings have important implications for the content and timing of interventions aimed at preventing the development of antisocial behaviour.

A later report will include an examination of differences between adolescents who engage in violent antisocial acts versus those who engage in non-violent antisocial acts, an investigation of factors which may have a protective effect against the development of adolescent antisocial behaviour, and an investigation of location effects on adolescent antisocial behaviour.

1. Introduction

This report is the product of the collaborative partnership between the Australian Institute of Family Studies and Crime Prevention Victoria. The partnership began in 2001 when Crime Prevention Victoria commissioned the Institute to analyse and collect data from the Australian Temperament Project concerning the development of adolescent and young adult antisocial and criminal behaviour. This report provides valuable new information, which it is hoped will improve our understanding of the factors that place an individual at risk of engaging in this type of behaviour and, in turn, inform early intervention efforts aimed at diverting individuals away from problematic pathways.

Adolescence is a critical period for the emergence and entrenchment of antisocial behaviours (including criminal behaviours), which for some, persist into adulthood and entail substantial costs for individuals, families and the community. It is widely recognised that early intervention and prevention can curtail the development of these problems and is preferable to reacting after the problem behaviour has become established. Greater success in universal and targeted interventions is predicated on improved understanding of the genesis of such behaviour. The Australian Temperament Project, a large scale longitudinal study, with twelve waves of data spanning the first eighteen years of life, provides a valuable opportunity to investigate the precursors of antisocial behaviour among Australian adolescents, and to examine a broad range of risk factors across developmental stages and domains of functioning.

The focus of this first report is on adolescent antisocial behaviour, which includes criminal acts such as theft or the selling of drugs, and dysfunctional behaviors1 such as running away from home or physical aggression. A brief overview of the research into adolescent antisocial behaviour is first presented, followed by a summary of the findings emerging from the current study and a discussion of their implications for the understanding of antisocial behaviour, as well as for policy development and early intervention and prevention efforts. For those interested in more a more detailed description of the findings, the appendices for this report can be obtained electronically from Crime Prevention Victoria's website, www.crimeprevention.vic.gov.au.

Nature and extent of adolescent antisocial behaviour

Information regarding the frequency and nature of antisocial behaviour among young people is typically obtained from a number of sources: (1) official statistics obtained from the criminal justice agencies (that is, police and courts), or (2) self-reported behaviour, generally obtained during the course of interviews or surveys (Rutter, Giller and Hagell 1998). Both types of information have advantages and disadvantages. Official statistics provide a measure of behaviours reported to and recorded by police. However, they provide a conservative assessment, since a high proportion of those committing antisocial acts are not apprehended, and many minor antisocial behaviours may not attract or warrant attention by authorities. Furthermore, particular groups, such as those from disadvantaged families and neighbourhoods, may be more likely to be the focus of official attention and hence have a greater likelihood of being apprehended (Rutter et al. 1998). Thus, official records provide an incomplete picture of the incidence of antisocial behaviours across different sections of the community.

Self-report has the potential to provide a more comprehensive picture and can cover a wider array of antisocial acts (not just those that are illegal), but may be affected by social desirability and other biases. It relies on the willingness of individuals to reveal potentially compromising information, and on respondents' veracity and memory. It is also reliant on the representativeness of the sample used, and researchers' ability to reach and engage the young people involved in serious antisocial acts. While recognising the advantages and disadvantages of both approaches, the current report focuses on adolescents' self-reported antisocial behaviour.

Antisocial behaviour among Australian adolescents

Studies examining rates of antisocial behaviour among Australian adolescents have found that it is very common for them to engage in some level of antisocial behaviour.

For example, in 1996, 441,234 New South Wales secondary school students in Years 7 to 12 were surveyed about their involvement in antisocial activities (Baker 1998). Close to 40 per cent of all students admitted to having attacked someone with the idea of hurting them at some time in their life, 38.6 per cent reported having purposely damaged or destroyed someone else's property, and over a fifth (22.8 per cent) had received or sold stolen goods. Significant age and gender differences were found, with rates for all types of offences peaking around Years 9 and 10 (14-16 years), and males reporting higher rates of each offence type, in each year level, almost without exception.

Further evidence of the high frequency of antisocial behaviour among Australian adolescents can be found in a Victorian survey of 8,984 Year 7, 9 and 11 students (Bond, Thomas, Toumbourou, Patton and Catalano 2000). Rates of antisocial behaviour generally increased from Years 7 to 9, but were relatively stable from Year 9 to Year 11. Consistent with Baker's (1998) findings, the peak incidence for most offences was in Year 9. The most common antisocial behaviours Year 9 students reported having been involved in during the past year were: stealing from a shop (30 per cent), engaging in graffiti (23 per cent), participating in a fight or a riot (18 per cent), carrying a weapon (18 per cent), and handling stolen property (18 per cent).

While these two studies used different time frames to assess engagement in antisocial behaviour (lifetime vs within the past year), some consistent trends are evident, particularly the escalation and peaking of antisocial behaviour in the mid teens. These trends are also reflected in official statistics.

Official statistics relating to antisocial behaviour among young people in Victoria, Australia.

- 16.5% of all persons proceeded against by Victoria Police in 2000/01 were aged between 10-16 years, compared with 38.2% who were aged 17-24 years, and 45.3% who were aged 25 years or over.

- 10-24 year-olds comprised approximately one-third of persons proceeded against for homicide and rape, half of all persons proceeded against for assault, and almost 60% of persons proceeded against for property offences.

- 15-19 years or 20-24 years are the peak ages of offending for homicide, assault, fraud, theft, burglary, vandalism and drug offences.

- 4-5 times as many young males are proceeded against by Victoria Police than young females.

Source: Victoria Police, Statistical Services Branch (2002).

Comparisons with international data

Studies that have examined rates of self-reported antisocial behaviour among adolescents in other countries have found similar patterns to those identified in Australia. That is, some degree of antisocial behaviour appears to be quite common among adolescents (Baker 1998; Rutter et al. 1998), to be more frequent among males than females, and typically peaks during midto- late adolescence. Nevertheless, there is considerable variation in rates across countries (Rutter et al. 1998). However, it should be noted that methodological differences between studies (for example, the representativeness of the sample employed, the measures of antisocial behaviour used, the time period during which participants were surveyed) make it difficult to directly compare rates of self-reported behaviour in different countries.

In summary, antisocial behaviour is common in adolescence. It ranges from relatively minor to quite serious acts, typically peaks during mid-to-late adolescence, and is more common among males than females. It has potentially serious consequences for adolescents both in the present and the future (Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington and Milne 2002), and impacts on their families and wider society (Homel et al. 1999).

Patterns of antisocial behaviour

In addition to investigating the nature and extent of antisocial behaviour in the community, considerable research has focused on differentiating between young people who exhibit distinct patterns of antisocial behaviour. Two such patterns, violent versus non-violent antisocial behaviour, and persistent versus experimental antisocial behaviour, will now be discussed.

Violent versus non-violent

Considerable research supports the notion that violent offenders are a small but distinct group from those who engage in nonviolent antisocial or criminal behaviour (Farrington and Loeber 2000; Loeber, Farrington, Rumsey, Kerr, Allen-Hagan 1998; Maughan, Pickles, Rowe, Costello and Angold 2000; Nagin and Tremblay 1999).

A comprehensive literature review undertaken by the United States Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention's Study Group on Serious and Violent Juvenile Offenders (Loeber et al. 1998) revealed a number of key differences between violent and non-violent offenders. These included the findings that: violent offenders are typically male; the majority of violent offenders tend to start offending earlier, and continue offending longer, than non-violent offenders; violent offenders tend to exhibit multiple problem behaviours (for example, substance use, mental health difficulties, authority conflict problems, aggression etc); and violent offenders tend to commit a range of aggressive and non-aggressive offences.

Further support for a differentiation between violent and non-violent offenders can be found in research that has attempted to chart developmental pathways to antisocial behaviour. For example, Maughan and colleagues (2000) examined the development of aggressive and non-aggressive conduct problems in a sample of 1419 American boys and girls. These authors found only a small degree of overlap between the developmental pathways for the aggressive and non-aggressive children. Similarly, a Canadian study of 1,037 males (Nagin and Tremblay 1998) identified unique developmental pathways for those who engaged in overt delinquency (for example, physical violence) and those who engaged in covert delinquency (for example, theft) during adolescence.

Nevertheless, some have argued against this distinction. Piquero (2000), for example, claims that the difference between violent and non-violent offenders is quantitative not qualitative. Piquero (2000) notes the consistent finding that violent offenders tend to commit more offences than non-violent offenders. Based on this observation, he suggests that the difference between these groups is more a matter of degree than type, in which case the correlates of one type of offence should be the same as another. Piquero (2000) tested this hypothesis on data from a sample of 987 American adolescents. After controlling for frequency of offending he found that only one variable differentially predicted violent, but not non-violent offending, namely, variation in intelligence test scores. Individuals with low intelligence scores were more likely to come into police contact for a violent offence by age 18 than those who scored highly on this measure.

While researchers should remain open to the idea that the difference between violent and non-violent offenders may be one of degree, differentiation into these subtypes appears to be a useful strategy for investigating the developmental pathways to adolescent antisocial behaviour.

Experimental versus persistent

Another distinction frequently made in the research literature relates to the stability or transient nature of antisocial behaviour.

Childhood and adolescence are periods of high experimentation, during which many young people engage in behaviours that are not pro-social (for example, shoplifting, lying, bullying, annoying peers etc) (Kelley, Loeber, Keenan, DeLamatre 1997). Nevertheless, while many young people act in an antisocial manner, this behaviour is usually transitory (Dussuyer and Mammalito 1998; Kelley et al. 1997; Moffitt and Harrington 1996). Individuals who engage in antisocial behaviour for a relatively short period of time and then desist, are often referred to as "experimenters". On the other hand, for a small group of people, antisocial behaviour is much more stable (Kelley et al. 1997; Moffitt and Harrington 1996), often beginning at a very early age and continuing well into adulthood. Those who maintain high levels of antisocial behaviour over long time periods are often labelled "persisters".

Consistent with the experimental – persistent distinction, Moffitt and colleagues (Moffitt and Harrington 1996; Moffitt, Caspi, Rutter and Silva 2001) propose two broad categories of antisocial behaviour: "life-course persistent" antisocial behaviour (which emerges early in life and persists well into adulthood); and "adolescent-limited" antisocial behaviour (which emerges alongside puberty and is transitory). According to these authors, adolescent-limited antisocial behaviour is quite common and may have few long-term deleterious consequences, whereas relatively few young people engage in life-course persistent antisocial behaviour.

Moffitt and colleagues (2001) tested this taxonomy in a sample of 922 males and females from the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study. They found that 200 participants fulfilled the criteria for adolescent-limited antisocial behaviour, whereas 53 met the criteria for life-course persistent antisocial behaviour. Life-course persistent antisocial behaviour was considerably more common among males than females, with approximately 10 males to every female displaying this pattern of antisocial behaviour, whereas the gender difference in adolescent-limited antisocial behaviour was small (1.5:1 males to females).

This distinction appears to be a critical one. However, relatively few studies have the requisite longitudinal data to allow the differentiation of such groups. The Australian Temperament Project, with data available at multiple timepoints from infancy onwards, has the capacity to investigate this important issue.

Theoretical models

Many models have been proposed to explain the development of antisocial behaviour. Some models propose different pathways leading to the development of antisocial behaviour. For example, Loeber and colleagues (Loeber, Wung, Keenan, Giroux, Stouthamer-Loeber, Van Kammen, and Maughan 1993) suggest that three different pathways can explain the development of antisocial behaviour in males. The first of these, the overt pathway, involves an escalation in aggressive acts (for example, minor aggression --> physical fighting --> physical violence) over time; the second, the covert pathway, involves an escalation in less overt antisocial acts (for example, minor covert behaviours --> property damage --> moderate to severe delinquency); while the third pathway, the authority conflict pathway, involves a sequence of stubborn behaviour, leading to defiance, and ultimately authority avoidance (for example, running away from home, truancy). Less serious behaviours precede more serious behaviours in these pathways and boys may proceed along more than one pathway at a time.

The Social Development model of Catalano and Hawkins (1996) emphasises the role of social learning in the development of antisocial behaviour. According to this model, children learn patterns of behaviour, whether they are prosocial or antisocial, from their family, their school, religious and other community institutions, and their peers. Hence, an individual's behaviour is determined by the predominant behaviours, norms and values held by those to whom the individual is attached. Consequently, youth attachment to prosocial individuals, developed particularly through involvement in rewarding experiences, is posited to be protective against the development of antisocial behaviours, conduct problems and substance use.

Weatherburn and Lind (2001) propose a role for economic stress in the development of criminal behaviour. According to their model, parents who experience higher levels of economic stress are more likely to neglect or abuse their children or engage in harsh, erratic and inconsistent disciplinary practices than other parents. This kind of parenting behaviour may lead a child to affiliate more strongly with their peers than their parents, making the child susceptible to the negative influence of antisocial peers. The effects of economic stress are reduced when parents have a strong social support network, but increase if such a support network is absent, or other sources of stress are present (for example, crowded household, large family, "difficult child", family conflict, parental disorder). Patterson, Reid and Dishion (1992) also suggest a critical role for parenting in the development of antisocial behaviour among males. They suggest that individuals who experience poor "basic training" as children are more susceptible to poor academic performance and peer rejection later on. These problems may lead to association with antisocial peers and engagement in antisocial acts in adolescence, and eventually, to poor adjustment in adulthood.

It should be noted that many of these "pathways" models have been developed to explain antisocial behaviour among males, with relatively little attention to antisocial behaviour among females.

Another approach to understanding the development of antisocial behaviour is the Risk Factors approach. A large body of research has been dedicated to the identification of risk and protective factors associated with the development of antisocial behaviour. Risk factors can be defined as those factors that "increase(s) the likelihood that a subsequent negative outcome will occur" (Loeber, 1990: 4), whereas protective factors operate in the context of risk and "offset risk factors and promote social development, well-being and resilience" (Bond et al. 2000: 3).

Risk and protective factors associated with the development of antisocial and criminal behaviour can occur across a number of domains. These include the characteristics of the child, the family and its experience of stressful life events, the school context, and community and cultural factors (Homel et al. 1999). The risk and protective factors that have most frequently been found to be associated with the development of antisocial and criminal behaviour are summarised in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Research suggests that no single risk factor can explain the development of antisocial behaviour. Rather, the more risk factors an individual is exposed to, the greater the likelihood that he or she will exhibit antisocial or criminal behaviour (Bond et al. 2000; Loeber and Farrington 2000). Similarly, the greater the number of protective factors possessed by a young person, the more likely he or she is to display resilience despite the presence of risk (Howard and Johnson 2000). Hence, the risk of a child becoming antisocial appears to be dependent upon the balance of risk and protective factors in their lives (Loeber and Farrington 2000).

| Risk Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child factors | Family factors | School context | Life events | Community and cultural factors |

| Parental characteristics:

Family environment:

Parenting style:

|

|

|

|

Source: Homel, Cashmore, Gilmore, Goodnow, Hayes, Lawrence, Leech, O'Connor, Vinson, Najman, & Western, 1999, p136. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Commonwealth Attorney-General's Department.

This approach emphasises the accumulation of risks as critical and treats the various risks factors as of equivalent importance. The question of whether different types of risks, or clusters of risk factors, have differential impacts remains as yet unanswered.

These are only some of the models that have been proposed to explain the development of antisocial and criminal behaviour. The current report does not try to provide a comprehensive review of current theoretical models. Rather, here we focus on one of the most widely used theoretical approaches in this field, the Risk Factor approach.

The present study

It is notable that much of the research into adolescent antisocial behaviour has been conducted in the United States, with influential work also originating in the United Kingdom, Europe, Canada and New Zealand. In addition, much of the research is based on samples suffering social and economic disadvantage and focuses primarily on males. Hence, the applicability of such research to the Australian context, to individuals in the general population, and to females, is uncertain.

There are very few Australian studies which have examined the pathways to antisocial behaviour from the early years onwards (an exception being Bor, Najman, O'Callaghan,Williams and Anstey 2001) although valuable research investigating more proximal influences has been conducted (for example, Baker 1998; Bond et al 2000; Homel et al. 1999; Weatherburn and Lind 2001 etc). Thus, our understanding of the precursors of and pathways to antisocial behaviour among Australian adolescents is very limited at present.

The present study attempts to redress this by analysing data on a sample of males and females representative of the general community who have been followed from infancy (4-8 months of age) into young adulthood. The Australian Temperament Project data set provides a valuable opportunity to investigate a wide range of risk factors for antisocial behaviour. The findings will provide guidance for early intervention and crime prevention efforts.

| Protective Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child factors | Family factors | School context | Life events | Community and cultural factors |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Homel, Cashmore, Gilmore, Goodnow, Hayes, Lawrence, Leech, O’Connor, Vinson, Najman, & Western, 1999, p138. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department.

1 Behaviours which fit the criteria for a diagnosis of Conduct Disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994)

2. The Australian Temperament Project

The Australian Temperament Project (ATP) is a longitudinal study of the psychosocial development of a large, representative sample of children born in Victoria between September 1982 and January 1983 (see Prior, Sanson, Smart and Oberklaid 2000 for a fuller account). Twelve waves of data on the children's temperament, behavioural and emotional adjustment, academic progress, health, social skills, peer and family relationships have been collected via annual or biennial mail surveys, with the aim of tracing the pathways to psychosocial adjustment and maladjustment across the children's lifespan.

A cohort of 2443 families from urban and rural areas was initially recruited via the following process. A stratified sample of Local Government Authority (LGA) areas, drawn to be representative of the state population, was developed using census data provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. All families with an infant of 4 to 8 months of age who attended a Maternal and Child Health Centre in one these LGAs during the first two weeks in May 1983 were invited to take part in the project. Comparison of the demographic profile of the cohort to census data showed that the obtained cohort was representative of the state's population. Approximately two-thirds of the original cohort continue to participate in the study after 18 years (N = 1650). Although there is an over-representation of low SES and ethnic families among those no longer participating, there are no significant differences between the retained and lost/withdrawn samples on any child characteristic assessed at infancy, and the family socio-economic profiles of the original and retained sample are very similar (Prior, Sanson, Smart and Oberklaid 1999). At each survey wave, the response rates have been approximately 80 per cent from those participating at that particular timepoint.

Parents have completed questionnaires about the child's functioning and aspects of their family life at every timepoint. Primary school teachers have supplied information about the ATP child in their class at the Preparatory Grade, Grade 2 and Grade 6 stages via mail surveys assessing a range of academic and individual child characteristics. From the age of 11-12 years (Grade 6), the children have completed questionnaires about their personal functioning, relationships with others, and beliefs and attitudes. Table 4 (pp.6-11) summarises the major domains assessed at each data wave. For most domains and at most survey waves, data are available from multiple sources.

In the three latest waves of data, at ages 13-14 years, 15-16 years and 17-18 years (that is, the years 1996, 1998, and 2000), adolescents answered questions about the incidence of antisocial behaviours, via an adaptation of the Self Report Delinquency Scale (Moffitt and Silva 1988).

In the sections that follow, we report the results emerging from the study and discuss their theoretical, preventative and early intervention implications.We present descriptive data on the frequency of antisocial behaviour during the adolescent years for the total sample, and for males and females separately. Following this, we report the identification and comparison of groups of persistently antisocial, transiently antisocial and non-antisocial youth. Finally, we investigate the relative impact of different types of risk factors and report analyses investigating gender differences.

| Age | Source of report | Domain | Construct/variable |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4-8 Months 1983 | Parent | Temperament |

|

| Relationship Quality |

| ||

| Behaviour Problems | e.g. sleeping difficulties, colic, excessive crying | ||

| Family demographics |

| ||

| Family Socio-Economic Status (SES) |

| ||

| Infant welfare sister | Birth & developmental history |

| |

| Relationship Quality |

| ||

| 1-2 Years; 2/3rds sampled 1984 | Parent | Temperament |

|

| Behaviour Problems | e.g. temper tantrums, excessive shyness, attention problems | ||

| Relationship Quality | MOR; as at 4-8 months | ||

| Family SES | As at 4-8 months | ||

| 2-3 Years; 2/3rds sampled 1985 | Parent | Temperament | As at 1-2 years |

| Behaviour Problems |

| ||

| Relationship Quality | MOR; as at 4-8 months | ||

| Family SES | As at 1-2 years | ||

| 3-4 Years; 1986 | Parent | Temperament |

|

| Behaviour Problems |

| ||

| Physical and language development | e.g. hearing problems, slow to talk, speech hard to understand | ||

| Family SES | As at 1-2 years | ||

| 5-6 Years 1988 | Parent | Temperament | As at 3-4 years |

| Behaviour Problems | As at 3-4 years | ||

| Relationship Quality | MOR; as at 4-8 months | ||

| Teacher | Temperament |

| |

| Behaviour Problems |

| ||

| School Readiness | e.g. cooperation with other children, relationship with teacher, self reliance, physical coordination | ||

| 7-8 Years 1990 | Parent | Temperament | As at 3-4 years |

| Behaviour Problems | As at 5-6 years | ||

| Relationship Quality | MOR; as at 4-8 months | ||

| Family SES | As at 1-2 years | ||

| Family Stress |

| ||

| Teacher | Temperament | As at 5-6 years | |

| Behaviour Problems | As at 5-6 years | ||

| Social Competance |

| ||

| Reading | ACER Word Knowledge test , assessing reading skills - select from 3 alternatives the word closest in meaning to a target word; e.g. 'tale' and 'end-story-sleep' | ||

| 9-10 Years 1992 | Parent | Temperament |

|

| Behaviour Problems | As at 5-6 years | ||

| Relationship Quality | MOR; as at 4-8 months | ||

| Social Behaviour |

| ||

| Family SES | As at 1-2 years | ||

| Family Stress | Total number of events in the past year that have had a negative effect on the family | ||

| 11-12 Years 1994 | Parent | Temperament |

|

| Behaviour Problems | As at 5-6 years; also

| ||

| Relationship Quality | MOR; as at 4-8 months | ||

| Social Skills |

| ||

| Peer Relationships | e.g. plays or talks with peers for extended periods of time, interacts with a number of different peers | ||

| Antisocial peer affiliations | e.g. Has friends who fight, steal, use drugs | ||

| Family demographics |

| ||

| Family Stress | As at 9-10 years | ||

| Teacher | Temperament | Task orientation; As at 5-6 years | |

| Behaviour Problems | As at 5-6 years; also Depression (parallel items to parent scale) | ||

| Social Skills |

| ||

| Academic Competence | e.g. reading and mathematics achievement, motivation, overall academic performance | ||

| Peer relationships | As for parent report 11-12 years | ||

| Child | Behaviour Problems | Parallel form of parent report at 11-12 years

| |

| Social Skills |

| ||

| Peer relationships |

| ||

| Self Concept |

| ||

| 12-13 Years 1995 | Parent | Temperament | As at 11-12 years |

| Behaviour Problems | As at 11-12 years | ||

| Relationship Quality | MOR; as at 4-8 months | ||

| Academic & Social Progress at School | e.g. understand the work in class, manage school rules and routines, finish assignments and homework | ||

| Family SES | As at 1-2 years | ||

| Family Stress | As at 9-10 years | ||

| Child | Behaviour Problems | As at 11-12 years | |

| Social Skills | As at 11-12 years | ||

| Eating attitudes and behaviour |

| ||

| Self Concept | About physical appearance e.g. have a good looking body, am better looking than my friends | ||

| Academic & Social Progress at School | Parallel scale to Parent scale at 12-13 years | ||

| 13-14 Years 1996 | Parent | Temperament | As at 11-12 years |

| Behaviour Problems |

| ||

| Relationship Quality | MOR; as at 4-8 months | ||

| Social Skills | As at 11-12 years | ||

| Peer relationships |

| ||

| Antisocial peer affiliations | As at 11-12 years | ||

| Academic & Social Progress at School | As at 12-13 years | ||

| Parenting Practices and Style |

| ||

| Parental smoking and drinking habits | Non, ex, occasional, moderate, heavy smoker / drinker | ||

| Family SES | As at 1-2 years | ||

| Family Stress | As at 9-10 years | ||

| Parental unemployment | During the past year | ||

| Teenager | Behaviour Problems |

| |

| Substance Use |

| ||

| Social Skills | As at 11-2 years | ||

| Emotional control | e.g. know how to relax when feeling tense | ||

| Curiosity scale |

| ||

| Academic & Social Progress at School | As at 12-13 years | ||

| Peer relationships |

| ||

| Antisocial peer affiliations | Friends' antisocial activities (e.g. get into fights, break the law) & substance use (e.g. alcohol, marijuana) | ||

| Family relationships | Parent attachment e.g. parents respect my feelings | ||

| 15-16 Years 1998. | Parent | Temperament | As at 11-12 years |

| Personality |

| ||

| Behaviour Problems | As at 13-14 years | ||

| Relationship Quality | MOR; as at 4-8 months | ||

| Social Skills | Assertiveness and Self control, as at 11-12 years | ||

| Academic & Social Progress at School | As at 12-13 years | ||

| Peer relationships | As at 13-14 years

| ||

| Antisocial peer affiliations | As at 11-12 years | ||

| Parenting practices and style | As at 13-14 years, but without Physical punishment scale | ||

| Family SES | As at 1-2 years | ||

| Family Stress | As at 7-8 years | ||

| Parental unemployment | During the past year | ||

| Teenager | Behaviour problems | As at 13-14 years | |

| Substance Use | As at 13-14 years | ||

| Personality | As for parent report 15-16 years | ||

| Sensation seeking | Thrill and adventure seeking e.g. attraction to activities such as parachute jumping, mountain climbing | ||

| Emotional control | As at 13-14 years | ||

| Social skills | Assertiveness | ||

| Bonding to School |

| ||

| Peer relationships | Friendship quality with best friends e.g. makes me feel good about myself | ||

| Antisocial peer affiliations | As at 13-14 years | ||

| Social responsibility, civic mindedness |

| ||

| Eating behaviours and attitudes | As at 13-14 years | ||

| 17-18 Years 2000 | Parent | Temperament | As at 11-12 years

|

| Personality | As at 15-16 years | ||

| Behaviour Problems | As at 13-14 years | ||

| Relationship Quality | MOR; as at 4-8 months | ||

| Academic & Social Progress at School | As at 13-14 years | ||

| Antisocial peer affiliations | As at 11-12 years | ||

| Parents' substance use | As at 13-14 years | ||

| Parental separation/ divorce/ death during child's life | Yes/ no | ||

| Family SES status | Parents' occupation and educational levels | ||

| Marital relationship during child's lifetime |

| ||

| Family Cohesion | e.g. know each others' close friends | ||

| Parent- adolescent conflict | e.g. have serious arguments, child thinks my opinions don't count | ||

| Parenting practices / style | As at 15-16 years; also

| ||

| Family SES | As at 1-2 years | ||

| Family Stress | As at 7-8 years | ||

| Teenager | Behaviour Problems | As at 15-16 years | |

| Substance Use | As at 15-16 years | ||

| Personality | As at 15-16 years | ||

| Emotional control | As at 15-16 years | ||

| School Bonding | e.g. I work hard to be successful; it's important to me to do well at school | ||

| Peer relationships |

| ||

| Relationships with parents |

| ||

| Teen coping styles |

| ||

| Self Concept | e.g. have a good opinion of myself, am as nice looking as most | ||

| Identity formation |

|

3. Frequency of antisocial behaviour

Adolescent participants were asked about their engagement in antisocial behaviours at three timepoints: 13-14 years (1996), 15-16 years (1998), and 17-18 years (2000). A summary of the questions used to assess antisocial behaviour is presented below. All questions relate to participant's behaviour within the past twelve months, with the exception of those concerning substance use, which refer to the past month.

As antisocial behaviour may be expressed in different ways at different ages (Moffitt et al. 2001), items were added to the scale at each timepoint, to accommodate age-related changes in the manner in which antisocial behaviour may be exhibited.

Australian Temperament Project assessment of antisocial behaviour

At 13-14 (1996), 15-16 (1998) and 17-18 (2000) years

- Got into physical fights with other people

- Damaged something in a public place ("on purpose" added from 15-16 years)

- Stolen something ("from a person or a house" added at 17-18 years)

- Driven a car without permission

- Been suspended or expelled from school

- Done graffiti in public places

- Carried a weapon ("e.g. gun, knife" added at 15-16 years)

- "Wagged" (skipped) school

- Frequency of cigarette use*

- Frequency of alcohol use*

- Frequency of marijuana use*

- Frequency of sniffing*

- Frequency of other drug use*

* These items relate to the past month.

Additional questions at 15-16 (1998) and 17-18 (2000) years

- Shoplifted

- Run away from home and stayed away overnight or longer

- Been in contact with, or cautioned by, police for offending

- Been charged by police

- Appeared in court as an offender

- Frequency of binge drinking*

- Frequency of drunkenness*

- Deleterious consequences of drinking alcohol*

* These items relate to the past month.

Additional questions at 17-18 (2000) years

- Sold illegal drugs

- Attacked someone with the idea of seriously harming them

- Been convicted in court of a criminal offence

- Deleterious consequences of marijuana and other drug use, including trouble with police*

- Substance dependence (alcohol, marijuana and other drugs).*

* These items relate to the past month.

Frequency of antisocial acts across the adolescent years

The frequency with which ATP participants reported engaging in each antisocial act is presented in Table 6. Data are presented for each of the three data waves in which this information was collected (that is, 13-14, 15-16, and 17-18 years). For clearer presentation of findings, antisocial acts have been grouped into five categories:

- those involving property offences,

- authority conflict problems,

- violent and drug-related antisocial acts,

- criminal justice contacts (as a consequence of antisocial acts), and

- substance use.

The trends emerging from this table will be discussed in detail later in this section.

Figures 1-5 pictorally display the proportion of individuals in the sample who reported engaging in the antisocial act on at least one occasion during the last 12 months.

| Antisocial act | Percentage who reported 'Not at all' | Percentage who reported 'Once' | Percentage who reported 'Twice or more' | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13-14 years | 15-16 years | 17-18 years | 13-14 years | 15-16 years | 17-18 years | 13-14 years | 15-16 years | 17-18 years | |

| Property | |||||||||

| Damaged | 86.3 | 78.6 | 79.5 | 10.7 | 13.5 | 11.4 | 3.0 | 7.9 | 9.1 |

| Driven | 96.5 | 93.0 | 85.6 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 7.7 | 1.1 | 3.2 | 6.7 |

| Graffiti | 91.2 | 87.5 | 91.2 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 4.8 | 2.5 | 5.9 | 4.1 |

| Shoplifted | -- | 87.0 | 90.5 | -- | 6.5 | 4.1 | -- | 2.7 | 5.3 |

| Theft | 84.1 | 79.4 | 90.2 | 11.0 | 11.3 | 6.5 | 4.9 | 9.3 | 3.3 |

| Authority | |||||||||

| Run Away | -- | 96.0 | 94.5 | -- | 2.5 | 3.3 | -- | 1.5 | 2.2 |

| Skipped school | 89.5 | 73.5 | 57.2 | 7.2 | 10.6 | 11.2 | 3.3 | 9.2 | 31.6 |

| Suspend/Expel | 95.4 | 93.0 | 95.1 | 3.3 | 5.2 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.3 |

| Violent/Drug | |||||||||

| Attacked | -- | -- | 94.7 | -- | -- | 3.4 | -- | -- | 1.8 |

| Fights | 66.2 | 67.4 | 76.9 | 20.7 | 19.2 | 14.8 | 13.1 | 13.4 | 8.3 |

| Sold Drugs | -- | -- | 94.4 | -- | -- | 1.7 | -- | -- | 3.9 |

| Weapon | 93.4 | 91.5 | 94.0 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 4.2 | 3.6 |

| Criminal Justice | |||||||||

| Charged | -- | 98.1 | 96.6 | -- | 1.4 | 2.5 | -- | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Contact | -- | 86.6 | 87.7 | -- | 10.6 | 8.1 | -- | 2.8 | 4.1 |

| Court | -- | 99.4 | 98.7 | -- | 0.4 | 1.0 | -- | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Convicted | -- | -- | 99.4 | -- | -- | 0.5 | -- | -- | 0.2 |

| Substance Use | |||||||||

| Alcohol* | 62.0 | 16.5 | 6.7 | 15.6 | 25.3 | 13.2 | 22.5 | 58.2 | 80.1 |

| Cigarettes* | 78.4 | 32.5 | 30.8 | 5.3 | 12.8 | 8.9 | 16.2 | 54.7 | 60.2 |

| Marijuana* | 93.6 | 46.2 | 52.8 | 4.9 | 20.8 | 18.7 | 1.4 | 32.9 | 28.5 |

| Other Drugs* | -- | 96.2 | 96.6 | -- | 2.4 | 1.7 | -- | 1.5 | 1.8 |

Note: * These variables relate to frequency during the past month (not year).

-- = Not assessed at this timepoint

Damaged = Damaged something in a public place on purpose; Driven = Driven a car without permission; Graffiti = Done graffiti in public places; Shoplifted = Shoplifted; Theft = Stolen something (from a person or a house); Run Away = Run away from home and stayed away overnight or longer; Skipped School = Skipped School; Suspend/Expel = Been suspended or expelled from school; Attacked = Attacked someone with the idea of seriously harming them; Fights = Got into physical fights with other people; Sold Drugs = Sold illegal drugs; Weapon = Carried a weapon (e.g. gun, knife); Charged = Been charged by police; Contact = Been in contact with, or cautioned by, police for offending; Court = Appeared in court as an offender; Convicted = Been convicted in court of a criminal offence; Alcohol = drank alcohol in last month; Cigarettes = Smoked cigarettes in last month; Marijuana = Used marijuana in last month; Other Drugs = Used other illegal drugs in last month.

Property offences

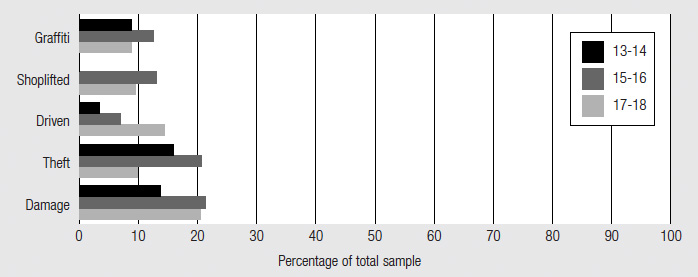

As shown in Figure 1, involvement in property offences, in particular, damaging public property and theft, was relatively common among ATP participants. Engagement in most property crimes appears to peak around 15-16 years of age in the ATP sample. The exceptions to this were driving a car without permission, which increased as participants approached the Victorian legal driving age (18 years), and property damage, which remained relatively stable between 15-16 and 17-18 years of age.

Figure 1: Property offences by age

Note: Graffiti = Graffiti drawing in public places; Shoplifted = Shoplifted; Driven = Driven a car without permission; Theft = Stolen something (from a person or a house); Damage = Damaged something in a public place on purpose.

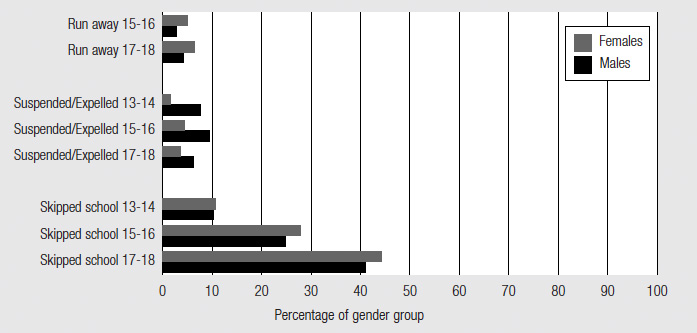

Authority conflict problems

Skipping school was a common occurrence among ATP participants with over 40 per cent of 17-18 year olds admitting that they had skipped school at least once during the past year (See Figure 2). The other authority conflict problems were much less frequent, with fewer than seven percent of participants in each data collection wave reporting that they had run away from home, and/or been suspended or expelled from school.

Figure 2: Authority conflict problems by age

Note: Run Away = Run away from home and stayed away overnight or longer; Suspended/Expelled = Been suspended or expelled from school; Skipped School = Skipped School.

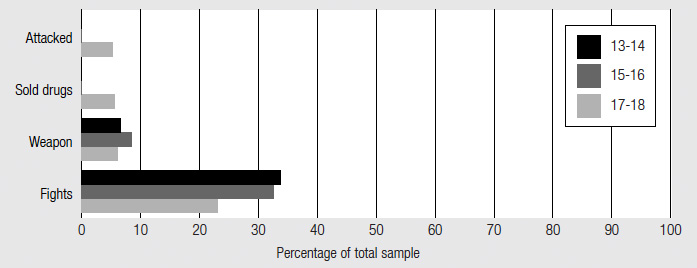

Violent and drug-related antisocial acts

As Figure 3 shows, involvement in physical fights was commonly reported. Approximately a third of the sample in 1996 (13- 14 years) and 1998 (15-16 years) reported that they had been in a physical fight with another person in the past year. However, by 2000 (17-18) the proportion of individuals engaging in physical fights had decreased quite markedly.

At 17-18 years of age, the proportion of individuals who reported having attacked someone with the intention of seriously harming them, having sold illegal drugs and having carried a weapon was very similar and quite low (between five and six percent). (Participants were not asked whether they had attacked someone or sold illegal drugs at ages 13-14 or 15-16). The proportion carrying a weapon was slightly higher at 15-16 years of age than at the other two ages.

Figure 3: Violent and drug-related antisocial acts by age

Note: Attacked = Attacked someone with the idea of seriously harming them; Sold Drugs = Sold illegal drugs; Weapon = Carried a weapon (e.g. gun, knife); Fights = Got into physical fights with other people.

Substance use

As mentioned earlier, all questions relating to substance use refer to participant's use within the past month.

As Figure 4 shows, the frequency with which participants engaged in all types of substance use increased with age. Consumption of alcohol was extremely common within the ATP sample, with almost 85 per cent of participants at 17-18 years of age reporting that they had consumed alcohol on at least one occasion during the past month. Cigarette smoking was also very common among this sample. Marijuana use was less frequent, peaking at just under 20 per cent by 17-18 years of age. The use of "hard" drugs such as amphetamines, designer drugs and opiates was very low.

Figure 4: Substance use by age

Note: Cigarettes = Smoked cigarettes in last month; Alcohol = drank alcohol in last month; Marijuana = Used marijuana in last month; Other drugs = Used other illegal drugs in last month.

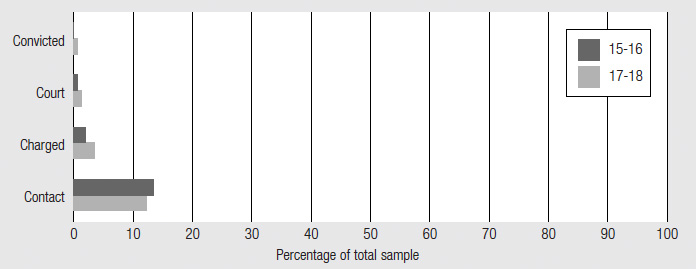

Criminal justice contacts

While a considerable proportion of participants aged 15-16 and 17-18 years reported having been in contact with the police for offending; the proportion of participants who had been charged with an offence, appeared in court as an offender, or convicted of an offence, was very small. However, Figure 5 suggests a slight increase in contact with the criminal justice system with age.

Figure 5: Criminal justice contacts by age

Note: Convicted = Been convicted in court of a criminal offence; Court = Appeared in court as an offender; Charged = Been charged by police; Contact = Been in contact with, or cautioned by, police for offending.

In summary, antisocial behaviour was quite common among the ATP adolescents. Property offences were one of the most common types of antisocial behaviour, with approximately 10-20 per cent of participants engaging in activities such as stealing and vandalism. Authority conflict and violent acts were much less common (generally less than 10 per cent) with the exceptions of skipping school (a high of 43 per cent at 17-18 years) and involvement in physical fights (a high of 34 per cent at 13-14 years). While cigarette and alcohol use were common (39 per cent and 85 per cent respectively, at 17-18 years), fewer participants had used marijuana (increasing from 6 to 19 per cent over the teenage years) and very few had used "hard drugs" (less than 4 per cent). About one in ten participants had been in contact with police for offending, but only a very small number had been charged (2-3 per cent), appeared in court (about 1 per cent), or been convicted of a crime (less than 1 per cent).

Frequency of antisocial acts among male and female adolescents

The proportion of males and females who reported engaging in each type of antisocial act are presented in Figures 6 to 10, while a detailed description of significant group differences is contained in Appendix 1.2 It should be noted that these graphs depict the relative proportion of males and females who reported engaging in each antisocial act at the separate timepoints.

Property offences

As shown in Figure 6, damaging public property (at all timepoints) and driving a car without permission (at 13-14 and 17-18 years) was noticeably more common among male ATP participants than female participants. On the other hand, a higher proportion of females than males reported engaging in graffiti in public places at 13-14 years of age. Rates of shoplifting and theft were fairly similar across males and females, except at 17-18 years, when a higher proportion of males admitted to having stolen something from a person or a house in the past year.

Figure 6: Property offences by gender

Note: Graffiti = Done graffiti in public places; Shoplift = Shoplifted; Driven = Driven a car without permission; Theft = Stolen something from a person or house; Damage = Damaged something in a public place (on purpose).

Authority conflict problems

Similar proportions of males and females reported skipping school and running away from home at each timepoint (see Figure 7). However, males were more likely to report having been suspended or expelled from school at 13-14 and 15-16 years.

Figure 7: Authority conflict problems by gender

Note: Run Away = Run away from home and stayed away overnight or longer; Suspended/Expelled = Suspended/expelled from school; Skipped School = skipped school.

Violent and drug-related antisocial acts

As Figure 8 shows, without exception, a higher proportion of males than females reported having sold illegal drugs, carried a weapon and been involved in a physical fight with others, at each timepoint. The proportion of males and females who admitted to having attacked someone with the intention of seriously harming them was fairly similar.

Figure 8: Violent and drug-related antisocial acts by gender

Note: Attacked = Attacked someone with the idea of seriously harming them; Sold Drugs = Sold illegal drugs; Weapon = Carried a weapon (e.g. gun, knife); Fights = Got into physical fights with other people

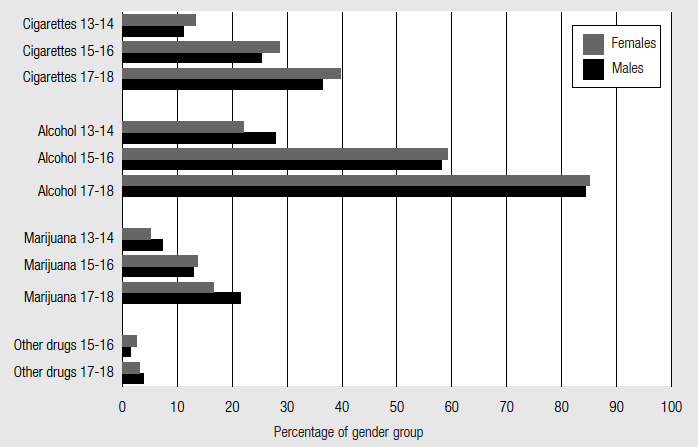

Substance use

Figure 9 shows that a similar proportion of males and females reported having smoked cigarettes, consumed alcohol, used marijuana and/or used hard drugs at all timepoints.

Figure 9: Substance use by gender

Note: Cigarettes = Smoked cigarettes; Alcohol = Drunk alcohol; Marijuana = Used marijuana; Other Drugs = Used other illegal drugs.

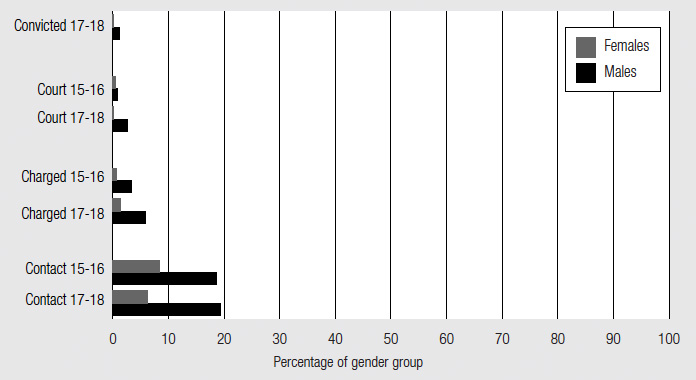

Criminal justice contacts

With the exception of 15-16 years, when a small but similar proportion of males and females reported having appeared in court as an offender, much higher proportions of males than females reported having been in contact with the criminal justice system at all timepoints (see Figure 10). This gender difference was most notable when comparing the proportion of males and females who had been in contact with, or cautioned by, police for offending (approximately 19 per cent males compared with 6-8 per cent females).

Figure 10: Criminal justice contacts by gender

Note: Convicted = Been convicted in court of a criminal offence; Court = Appeared in court as an offender; Charged = Been charged by police; Contact = Been in contact with, or cautioned by, police for offending.

In summary, cigarette and alcohol use were the most common antisocial behaviours across both sexes, with cigarette use escalating from approximately one-in-ten adolescents at 13-14 years to four-in-ten adolescents at 17-18 years, and alcohol use from one-fifth to four-fifths of adolescents over the same time period. Skipping school was also quite common, increasing from one-in-ten at 13-14 years to four-in-ten at 17-18 years for both males and females.

For males, involvement in physical fights was relatively common (an incidence of 34-54 per cent) – although diminishing with age – while property damage escalated from one-fifth in early adolescence to one-third in late adolescence. Onein- five males had been in contact with police for offending, while 10-20 per cent had committed theft, driven a car without permission, or used marijuana. Around 10 per cent males had shoplifted, engaged in graffiti, or carried a weapon. Between 5-10 per cent had been suspended or expelled from school, while approximately 5 per cent had attacked someone with the idea of seriously harming them, sold drugs, run away from home, or been charged by police.

For females, engaging in physical fights and property offences were the most common types of antisocial behaviour, with rates of approximately 10-15 per cent for all types of offences. Marijuana use was the next most frequent behaviour, ranging from 5-16 per cent from early to late adolescence. Just over 5 per cent females had been in contact with police for offending and a similar proportion had run away from home. All other types of antisocial behaviour were extremely rare, at lower than 5 per cent occurrence.

2 Copies of the appendices are available in an electronic format from Crime Prevention Victoria's website, www.crimeprevention.vic.gov.au.

4. Formation of persistent, experimental and low/non antisocial groups

To assist with the identification of risk factors for the development of antisocial and criminal behaviour, participants were grouped on the basis of their pattern of antisocial behaviour over three data collection points (13-14 years, 15-16 years, and 17-18 years).

First, individuals were classified as displaying high or low levels of antisocial at each timepoint. An individual was classified as displaying high levels of antisocial behaviour at a particular timepoint if he or she reported engaging in three or more different antisocial acts during the previous 12 months,3 while those who reported fewer than three different antisocial acts within the previous 12 months were classified as displaying low levels of antisocial behaviour at that timepoint.

Some acts (i.e. alcohol use, cigarette use, and skipping school), while socially undesirable and/or officially illegal at these ages, were so common within the sample as to appear almost normative. These behaviours were therefore not included in the definition of antisocial behaviour. Contact with the criminal justice system was also excluded from our definition as contact with this system is not an antisocial act in itself, but usually results from an antisocial act being detected.

Consequently, to be classified as being high in antisocial behaviour, an individual must have engaged in three or more of the following behaviours on at least one occasion during the past 12 months:

- been in physical fights with others;

- damaged something in a public place on purpose;

- stolen something (from a person or a house);

- driven a car without permission;

- been suspended or expelled from school;

- engaged in graffiti in public places;

- carried a weapon (for example, gun, knife);

- shoplifted; run away from home or stayed away overnight or longer;

- sold illegal drugs;

- attacked someone with the idea of seriously harming them;

- used marijuana (within the past month);

- used hard drugs, such as amphetamines, cocaine, designer drugs or opiates (within the past month)

Using this criterion, 12.4 per cent of participants in at 13-14 years (1996), 19.7 per cent of participants at 15-16 years (1998) and 20.0 per cent of participants at 17-18 years (2000), exhibited high levels of antisocial behaviour.

Patterns of antisocial behaviour over time

We next examined the data for the three timepoints to identify patterns of behaviour across time. For some participants, data were available for only two timepoints. These data were included if the level of antisocial behaviour was consistent across both survey waves (for example, both high, both low). Individuals who were high at one timepoint and low at the other were not included, as the absence of information from the third timepoint made it difficult to determine whether behaviour patterns were transient or stable. A further condition for inclusion was that data must be present at 17-18 years, so that participants' current levels of antisocial behaviour could be ascertained. Eight patterns of antisocial behaviour were identified (see Table 7).

Using the Experimental-Persistent typology (Kelley et al. 1997; Moffitt et al. 2001; Moffitt and Harrington 1996) as a guide, the eight groups were combined into three larger groups based upon the stability of their antisocial behaviour:

- "Low/non antisocial" – these participants displayed low or no antisocial behaviour at all timepoints that data were available for them (Group 1 in Table 7).

- "Experimental" – these participants exhibited high antisocial behaviour at one timepoint only and appeared to have desisted (Groups 2 and 3 in Table 7).

- "Persistent" – these individuals reported high antisocial behaviour at two or more timepoints, including the latest timepoint (Groups 6, 7 and 8 in Table 7).

Individuals who displayed high antisocial behaviour at only 17-18 (Group 4 in Table 7) were not included in the experimental group as, in the absence of follow-up data, it could not be determined whether their behaviour was of a transitory nature. In addition, participants who exhibited high antisocial behaviour at ages to 13-14 and 15-16 years but not 17-18 (Group 5), were excluded from the persistent group because although they exhibited persistent antisocial behaviour over two waves of data collection, they had desisted by 17-18 years. Hence, they did not fit with the other groups (6, 7, and 8) who were still actively antisocial at the last data collection wave. The three groups formed on the basis of the criteria above are summarised in the right-hand column of Table 7.

| Pattern | Group |

|---|---|

| 1. Low (or none) at all times (n=844) | LOW/NON ANTISOCIAL (n=844) |

| 2. High at 13-14 only (n=23) | EXPERIMENTAL (n=88) |

| 3. High at 15-16 only (n=65) | EXPERIMENTAL (n=88) |

| 4. High at 17-18 only (n=80) | |

| 5. High at 13-14 and 15-16 (n=23) | |

| 6. High at 15-16 and 17-18 (n=61) | PERSISTENT (n=131) |

| 7. High at 13-14 and 17-18 (n=22) | PERSISTENT (n=131) |

| 8. High at all times (n=48) | PERSISTENT (n=131) |

Note: Low = Low antisocial behaviour; High = High antisocial behaviour

Group characteristics

Gender

The gender composition of the three groups is shown in Table 8. It can be seen that there were more males than females in the persistent group, and somewhat fewer males than females in the other two groups.4 The male:female ratio in the persistent group is consistent with the New Zealand trends reported by Moffitt et al. (2001), although it is less pronounced.

While not significant, the slightly higher proportion of females in the experimental group is at odds with Moffitt's findings of slightly more males than females in the adolescent-limited group. These differences could be a result of somewhat different group selection methods; sampling differences (the ATP study includes urban and rural participants while the New Zealand study is of urban participants; and the ATP has a larger sample); time of survey effects (the New Zealand data on antisocial behaviour was collected in the mid to late 1980s while the comparative ATP data was collected in the mid to late 1990s); cultural differences; or differential attrition effects (the New Zealand study has had lower rates of attrition than the ATP study).

Table 8 also shows that ATP males, if antisocial, were much more likely to be persistently antisocial, while females were equally likely to be persistent or experimental.

| Group | Male | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % of males | % of group | n | % of females | % of group | ||

| Low/Non Antisocial | 345 | 73.7 | 40.9 | 499 | 83.9 | 59.1 | |

| Experimental | 38 | 8.1 | 43.2 | 50 | 8.4 | 56.8 | |

| Persistent | 85 | 18.2 | 64.9 | 46 | 7.7 | 35.1 | |

Profile of antisocial behaviours in the three groups

The three groups were compared on the criteria used to define antisocial behaviour, as shown in Table 9. It can be seen that a higher proportion of the persistent group engaged in all types of antisocial behaviour at all timepoints than adolescents in the low/non antisocial group.