Towards COVID normal: Child care

Families in Australia Survey report

June 2021

Download Research report

Overview

The child care sector in Australia, as in other countries, was significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. These effects were partly related to restrictions and health concerns and partly related to changes in parental employment and finances.

This report looks at families' experiences of child care, and includes reports on how use was affected by COVID-related restrictions over May-June 2020 and also child care use at November-December 2020. It draws on findings from the first and second surveys of the AIFS Families in Australia Survey series.

Key messages

-

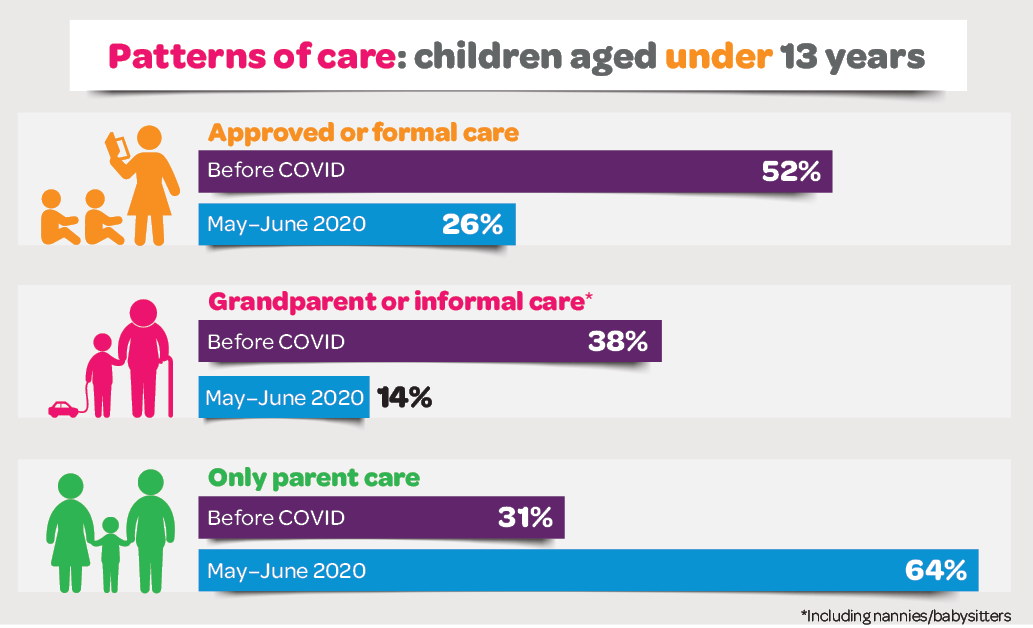

In response to COVID impacts but ahead of the introduction of the Child Care Fee Relief Package, many children had been withdrawn from child care, both formal and informal. At May-June 2020, 26% of parents with children under 13 years were using approved or formal care, compared to 52% before COVID, and 14% were using grandparent or other informal care compared to 38% before COVID. By the second survey, in November-December 2020, the rates of formal child care use were similar to those reported for before COVID.

-

Among families that stopped or changed care arrangements up to May-June 2020, the main reasons were concerns for children's health (44%) and because parents were at home (32%).

-

About three in four child care users report their child care fully meets their needs. The proportion is lower (66%) in families that only use informal child care.

-

Key issues that emerge as barriers to access to formal care, among those that have some unmet demand for formal care, are cost and availability.

Child care during COVID

Effects on child care

In the first half of 2020, the early childhood education and care sector was first impacted by COVID, with lower attendance in formal (or approved) care services (which includes centre-based day care (CBDC), outside school hours care (OSHC) and family day care (FDC)) particularly noticeable. The informal provision of child care was also affected. This care is often provided by grandparents, and was affected both by restrictions and heightened concerns over protecting the health of older Australians (Carroll, Budinski, Warren, Baxter, & Harvey, 2021).

Box 1 summarises the ways that child care assistance, and support to the early childhood education and care sector, was rolled out by the Australian Government in 2020. At the time of the first survey, in May-June 2020, the Child Care Fee Relief Package had been introduced. This brought in free child care in April to July 2020. (See also, Koslowski, Blum, Dobrotić, Kaufman, & Moss, 2020, for an international perspective on approaches that had been brought in across a number of countries by this time.)

Box 1: Child care policy changes during COVID-19

A dramatic fall in the numbers of children in early childhood education and care services led to some service closures and widespread concern about the viability of the sector. Measures taken by the federal government were included in the Relief Package (6 April-12 July), the Transition Payment (13 July-27 September 2020) and the Recovery Package (28 September-31 January 2021). The following provides a summary of the key aspects of this support, but for more details see the Department of Education Skills and Employment's COVID-19 information for the early childhood education and care sector.

- The Relief Package suspended the usual form of child care assistance (the Child Care Subsidy and Additional Child Care Subsidy) that is paid to services to subsidise families' child care use based on each child's eligibility. Services were subsidised through weekly payments - the amount services received was based on fees charged in a fortnight in February 2020. It was intended services would also access other measures in place to support child care services, or businesses more generally, through the pandemic. Through these arrangements, services were to provide child care to families free of charge. To receive government assistance, child care services needed to remain open, and they were advised to prioritise care to children of essential workers, vulnerable and disadvantaged children, and previously enrolled children.

- During the period of the Transition Payment, child care services returned to normal funding arrangements, and parents were to again pay for child care subsidised through the Child Care Subsidy. Services also received a Transition Payment equal to 25% of the average weekly fees charged by their services during a reference fortnight. The Recovery Package involved the extension of access to the Transition Payment for jurisdictions with continuing COVID impacts, including an additional payment for OSHC services. This applied, in particular, to services in Victoria. Additional support was available for services that were at risk of imminent closure.

- With the reintroduction of the Child Care Subsidy and paid child care from July 2020, parents' subsidy entitlement was again subject to the income and activity test that accompany the Child Care Subsidy. However, there were activity test exemptions until April 2021 for those whose work continued to be affected by COVID. For families, there were also adjustments made to the number of allowable absences - that is the number of days for which the Child Care Subsidy would still be available even if children were absent from child care.

- Research and stakeholder consultation was undertaken by the Department of Education, Skills and Employment in 2020 about the early childhood education and care sector, the impacts of COVID-19 and the above measures. Refer, for example, to Early Childhood Education and Care and COVID-19: Path to Recovery and other reports listed on COVID-19 information for the early childhood education and care sector.

Patterns of care

In response to COVID impacts but ahead of the introduction of the Child Care Fee Relief Package, many children had been withdrawn from child care, both formal and informal. This withdrawal from child care was a response to parental job losses, increased rates of working at home, and financial and health concerns. At May-June 2020, even with the introduction of free child care, some parents had not returned children to child care.

At this time, of families with children aged under 13 years:

- 26% were using approved or formal care

- 14% were using grandparent and other informal care

- 64% were using only parent care.

This compares to the percentages for earlier in 2020. Parents reported on the care arrangements they used before COVID:

- 52% were using approved or formal care

- 38% were using grandparent and other informal care (including nannies or babysitters)

- 31% were using only parent care.

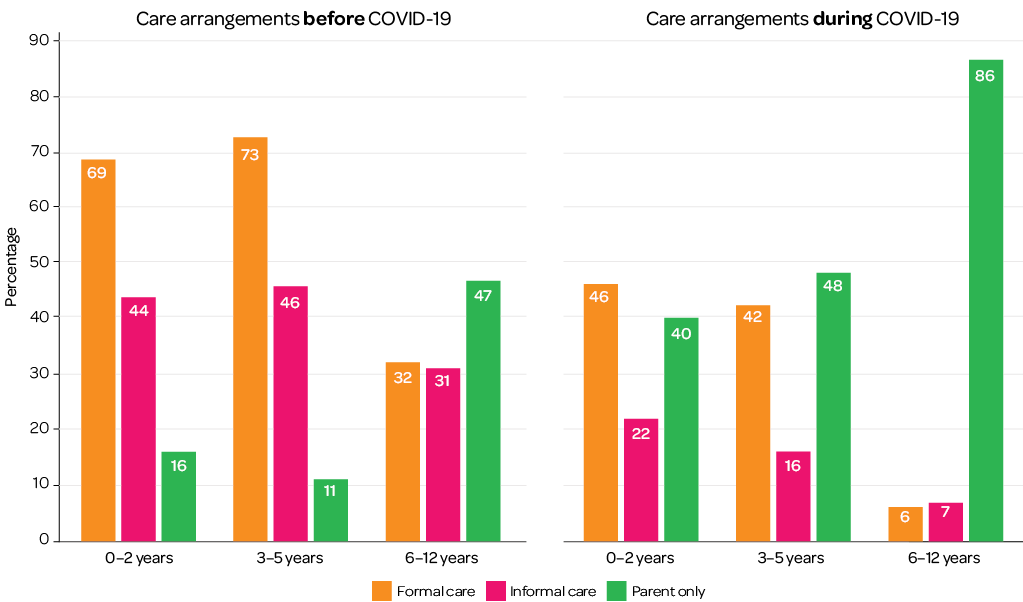

These care arrangements, before COVID and at May-June 2020 varied by the age of the youngest child. There were very significant declines in the use of any child care in families with a youngest child aged 6-12 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1: All care arrangements for children under 13 years, by age of youngest child, before COVID-19 and during COVID-19

Source: Families in Australia: Life during COVID-19, May-June 2020

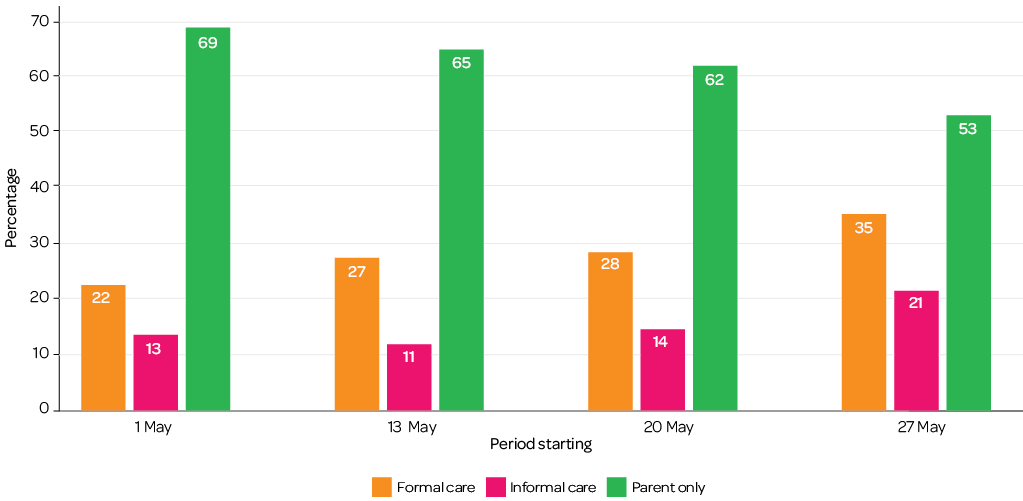

During the time of data collection for the first Families in Australia Survey, families were responding to the introduction of free child care, with participation in child care increasing while data were being collected. The participation rates for all families with children under 13 years is shown in Figure 2, by when the survey was completed.

Figure 2: All care arrangements for children under 13 years for May-June 2020, by period of data collection

Source: Families in Australia: Life during COVID-19, May-June 2020

Changes in child care use

Families that used formal care before COVID-19 were asked in May-June 2020 about changes to this care.

- 20% reported that their formal care use at May-June 2020 was the same as before COVID and they kept using it throughout

- 15% reported they changed formal care arrangements (hours, days, the service used)

- 17% reported that they were using child care at May-June 2020 but they had stopped using it for a while

- 5% reported doing different things for different children/care arrangements

- 52% had stopped using formal care.

Families who were using formal care before COVID-19, who stopped or varied their child care use by May-June 2020, stopped or varied it for the following reasons:

- 44% had concerns about the child/children's health

- 32% had a parent/parents at home to care for children

- 19% had concerns about the health of the care provider

- 19% said their service was restricted to essential workers or vulnerable families

- 10% had financial constraints

- 5% said their child care service closed

- 3% for reasons not related to COVID.

Some comments from survey respondents explain their reasons for changing or not changing their different child care arrangements (including formal and informal child care).

We had no choice but to continue using grandparents for child care as I had to continue working as a nurse and my husband had to work from home as a teacher.

Female, aged 44

It hasn't changed, as our child care arrangements have not changed. I have chosen to keep my child in their usual hours so I can use my extra time at home for cleaning and cooking, which means we get focused family time.

Female, aged 36

Grandparent care has replaced paid child care. The reason we withdrew our son from child care was so that we could continue to see his grandmother, who lives alone and wanted to keep seeing us to avoid negative mental health impacts of social isolation.

Female, aged 31

My hours were forcibly reduced, so rearranged child care accordingly, then we had the option to go back to original hours, but couldn't rearrange child care back to original level. So remaining on reduced hours until I can. Though I quite like reduced hours during the stress of lockdown.

Other gender, aged 34

While our child care centre doesn't have explicit rules excluding us from sending the kids they are strongly encouraging kids to continue to stay home if possible, they have reduced their opening hours by 2 hours/day and they have requested people reduce the numbers of days their children attend (if they are attending at all).

Female, aged 32

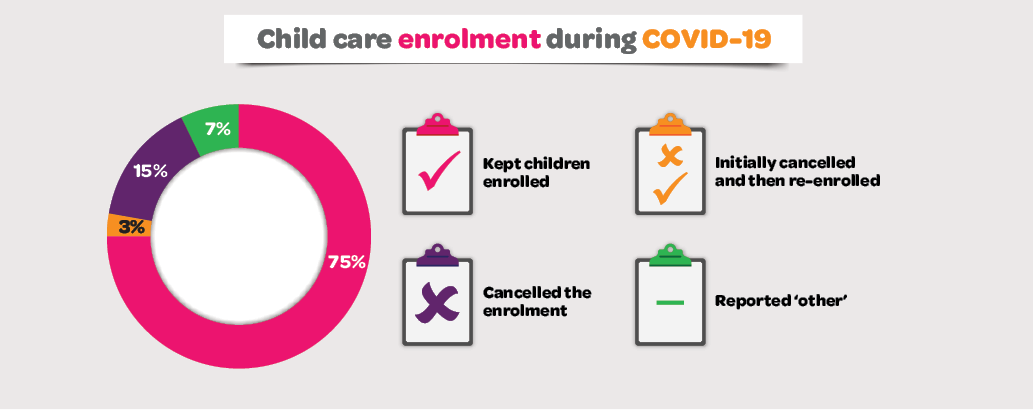

Child care enrolment

One of the issues that occurred early in the COVID-19 restrictions was that families withdrew children from child care and cancelled their enrolment to avoid paying fees. With the introduction of free child care, families were encouraged to re-enrol their children to ensure their place was held at the service. We asked parents who reported stopping using child care, what they did in terms of children's enrolment. Overall, of those who previously used formal care but who were not using it at the time of the survey:

Some comments regarding other arrangements included those that pointed out they had cancelled some arrangements but kept others. Those who had stopped using care for financial reasons were more likely than others to have cancelled their children's enrolment.

Free child care

As noted above, free child care had been introduced prior to the survey in May-June 2020. This was often remarked on by parents, in answering questions about their financial wellbeing at the time. For example:

It has been great for us to not have to worry about child care fees during COVID-19 due to the reduced income of my husband.

Female, aged 39

If anything, our financial wellbeing has improved with less expenditure on eating out and activities. We have also saved a lot of money on free child care. As high-income earners, we are not eligible for any child care benefits. We usually outlay about $1,200 on child care a fortnight.

Female, aged 34

The government's free child care made a HUGE difference for us financially. It reduced an enormous amount of stress and allowed us to shave our household debt in just a few months.

Male, aged 29

A number of survey respondents worked as educators in the early childhood education and care sector and reported experiencing financial difficulties due to the availability of free child care. This was also reflected in some parent responses. For example:

I had to drop two days of work when the subsided child care package came into effect because my Family Daycare Educator couldn't afford to operate her business.

Female, aged 36

Other parents expressed having found it difficult to find the child care they need because of child care services being at capacity.

Because my partner has received Job Keeper, he is able to perform child care duties as I return to work from maternity leave. This is fortunate to an extent as I have not been able to find child care for my child since the free care was announced. My child has been on a number of waiting lists since birth but all of the local child care centres are at capacity as no-one is dropping their enrolments.

Female, aged 34

Child care at the end of 2020

Patterns of child care use

By November-December 2020, restrictions related to COVID had eased in many jurisdictions across Australia, and some of the more extreme impacts of COVID on employment had also started to ease. See, for example, the analysis of parents' working at home, using Families in Australia Survey data from November-December 2020, which shows that rates of working at home at this time were lower than they had been in May-June 2020 when the Families in Australia Survey was first conducted (Baxter & Warren, 2021). The Relief Package ended in July 2020, with parents again paying for child care from 13 July 2020, and the Child Care Subsidy was reintroduced (see Box 1 for details).

At November-December 2020, among parents with children aged under 13 years:

- 29% used only formal care (CBDC, OSHC or FDC)

- 17% used only informal care (grandparents, etc.)

- 18% used both

- 36% used no child care, with children only cared for by parents/guardians.

These proportions are very similar to the before-COVID child care patterns, as reported by parents in the first Families in Australia Survey. According to that survey, before COVID:

- 31% used only formal care (CBDC, OSHC or FDC)

- 17% used only informal care (grandparents, etc.)

- 21% used both

- 31% used only parental care.

At November-December 2020, patterns varied by age of youngest child, as is usually the case in exploring patterns of child care use (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Type of care used at November-December 2020, by formal or informal and age of youngest child

Source: Families in Australia: Towards COVID Normal, November-December 2020

Whether child care needs were met

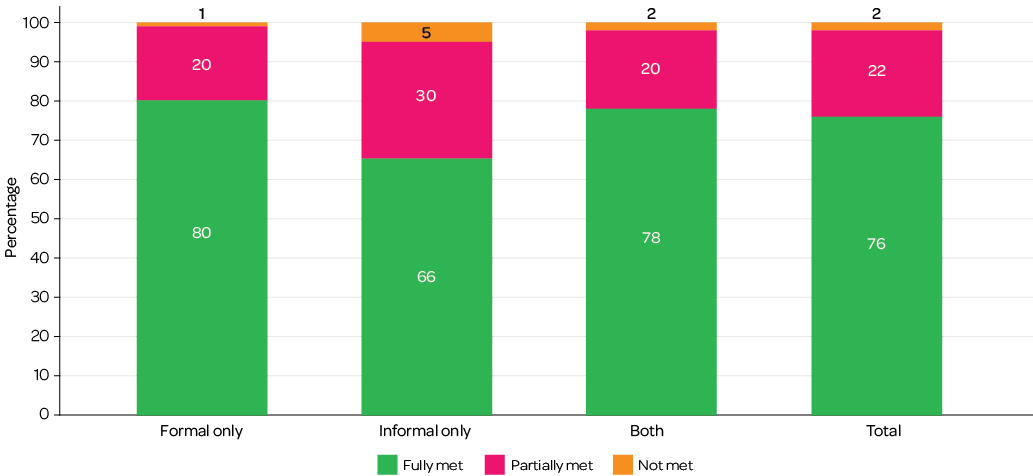

Most parents who were using some form of child care at November-December 2020 reported that the child care they were using fully met their needs (76%). Though this was a little less true among those using only informal care (66%), as a higher proportion of these parents reported that their child care needs were only partially met. Overall, 22% of parents said their child care needs were partially met, leaving only a very small number indicating that their child care needs were not being met with their current arrangements. See Figure 4.

Figure 4: Whether parents' child care needs were being met, those using some child care at November-December 2020, by care type

Source: Families in Australia: Towards COVID Normal, November-December 2020

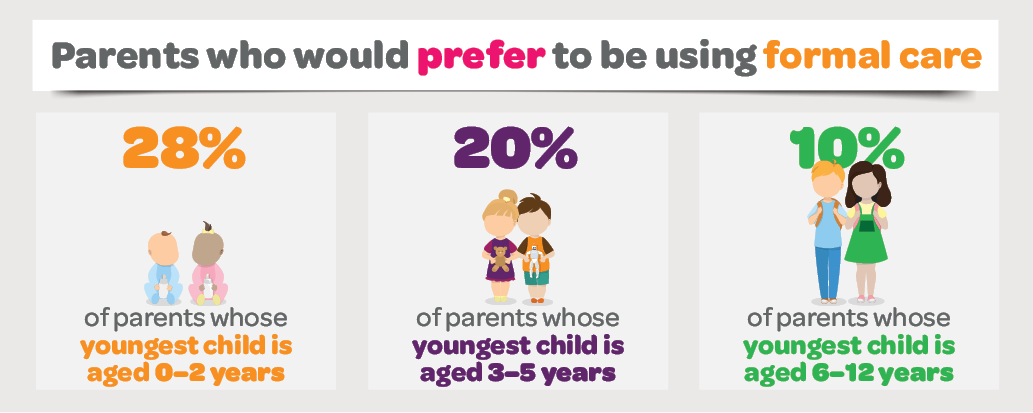

Parents who were not using formal care at the time of the survey were asked whether they would have preferred to be using formal care. Overall, 19% said they preferred to use formal care.

Of those not using formal care:

Those that had some unmet demand for child care were asked what barriers they faced in accessing their preferred care arrangements. The key issues that emerged in relation to access to formal care were cost and availability. In referring to cost, parents sometimes indicated they were not using formal care at all because of the cost, or they were using less care than they wanted to use. In regard to availability, parents referred to long waitlists and no places available at all.

Is too expensive and can't afford having her five days as I work full-time from home mostly but need to meet clients. Is very hard.

Female, aged 42

I would like to increase her centre days and reduce burden on family but getting extra days at care is hard and takes months.

Female, aged 32

Many referred to their work situation and how it intersected with their care needs, or their challenges in finding suitable care. Some noted their need to adjust work arrangements to better fit around the child care they had available. Some had to make more use of family or friends, given formal care options did not fit with their work arrangements. For example, shift workers or those starting early or finishing late referred to service operating hours not meeting their needs (e.g. in relation to care outside of standard hours). Those with intermittent, casual or uncertain work arrangements referred to the challenges of arranging child care when work arrangements are not locked in. This was also linked to affordability worries as parents felt they could not afford child care in between periods of work.

I need to be at work by 7 am. It is next to impossible to make that happen when OSHC services operate from 6.30 am onwards. It is a massive barrier to work as a female tradesperson (plumber).

Female, aged 30

See also Baxter, Hand, and Sweid (2016) for related research on flexible work and child care arrangements.

Parents also discussed specific issues related to COVID, with some reporting to have had difficulties finding a child care place following taking children out of child care in 2020. Many parents also referred to how more stringent rules about children staying at home from child care when unwell had posed challenges managing their work and care responsibilities.

Some parents referred to their wish for care arrangements other than centre-based care, including having a preference for family-based care (e.g. grandparents) or for a nanny or babysitter. During 2020, families experienced some challenges in accessing family-based carers given COVID restrictions and desires to protect the health of family members.

Other parents referred to specific situations that posed challenges in accessing suitable child care. For example, parents of children with additional needs had some particular challenges.

My autistic child is easily overwhelmed by centre care. So we opt to only do before school care for her and negotiate flexible work arrangements so she does not need to attend after school care. Access to outside school hours care that suits neurodiverse kids would be a huge benefit.

Female, aged 38

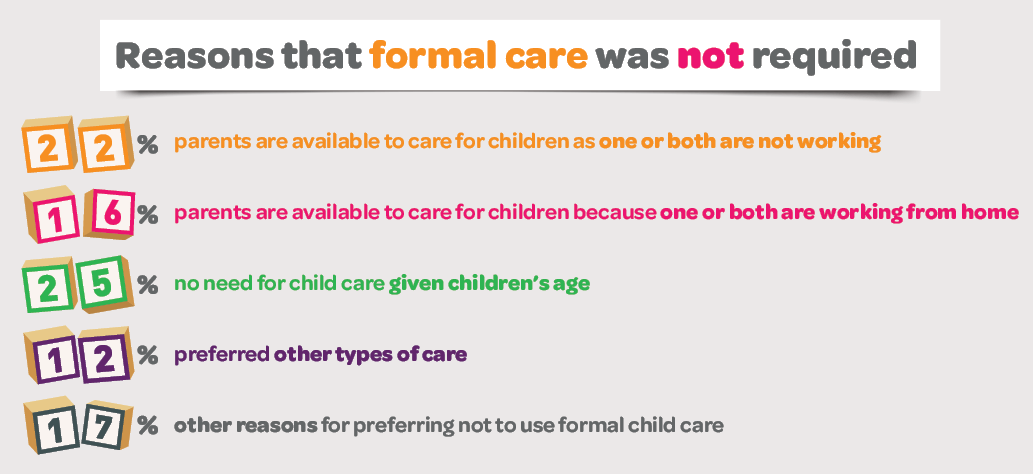

Those who were not using formal child care but indicated they did not need it were most likely to indicate this care was not needed because of parent availability or because of the child's age:

Summary

In 2020, child care patterns were significantly disrupted by the affects of COVID and related restrictions, as well as financial and health concerns, and parents more often working at home. The introduction of free child care for some months in 2020 was a major change for families and the child care sector. However, by the end of 2020, free child care had ended and patterns of child care use were similar to those at the beginning of 2020. In reporting on child care experiences at this time, if reporting on barriers parents typically referred to issues of access, affordability and flexibility in formal child care. However, many families also acknowledged the valued role of grandparents in helping to provide child care.

About the survey

Towards COVID Normal was the second survey in the Families in Australia Survey (AIFS' flagship survey series). It ran from 19 November to 23 December 2020, when restrictions had been eased in most states.

The pandemic in Australia triggered an unprecedented set of government responses, including the closing of Australia's borders to non-residents, and restrictions on movement, gatherings and 'non-essential' services.

Although the health consequences over the period were not as severe in Australia as they were in many countries, social and economic effects were profound. The Towards COVID Normal survey attempted to capture some of those effects. The survey was promoted through the media, social media, newsletters, internet advertising and word of mouth.

This report also draws on data from the first survey - Life during COVID-19 - which ran from 1 May to 9 June 2020, when all states were in various stages of lockdown.

Survey participants

- In the first survey, there were 7,306 respondents to the survey, of which 6,435 completed all survey questions. The analysis presented here is based on the sample of 2,244 parents with children aged under 13 years.

- In the second survey, 4,866 participants responded, of which 3,627 completed all survey questions. As for the first survey analysis, the analysis presented here is based on the sample of 2,167 parents with children aged under 13 years. That is, while the total sample for the second survey was markedly smaller than the first, the number of respondents who were in scope for answering the child care questions was only slightly smaller in the second survey.

Author: Jennifer Baxter

Editor: Katharine Day

Graphic design: Lisa Carroll

Featured image: GettyImages/Marisa9

Baxter, J. (2021). Towards COVID normal: Child care in 2020. (Families in Australia Survey report). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.