Use of health services among children at risk of social‑emotional problems

Opportunities for early intervention

March 2020

Diana Warren, Brendan Quinn, Galina Daraganova

Download Research report

Overview

Using data from both Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) and Medicare, this paper examines patterns of health and support service use among Australian children, especially among those at elevated risk of experiencing poor social-emotional wellbeing and psychological adjustment.

Social-emotional wellbeing and psychological adjustment were assessed using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire over five data collection periods or 'waves'; that is, every two years from when children were aged 4-5 to 12-13 years. Specifically, children were assessed to determine their 'risk' of experiencing emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, conduct problems and low prosocial skills. Descriptive analyses examined differences in health service use at each timepoint; multivariate longitudinal analyses more comprehensively investigated the characteristics of children and their families who were most likely to access various types of professional support in Australia, with a focus on the effect of elevated risk of experiencing poor social-emotional wellbeing and psychological adjustment on service use among Australian children and families.

This research was commissioned by Emerging Minds: The National Workforce Centre for Child Mental Health.

Key messages

-

The percentages of children using specific medical services as reported by parents varied with age; however, overall, general practitioners (GPs) were the most commonly used service by study children.

-

Children at increased risk of social-emotional problems had higher rates of contact with various service types, including psychiatric and behavioural therapy services, other medical professionals including GPs, paediatricians and speech therapists, in addition to hospital emergency and outpatient services.

-

Medicare data indicated that the usage rates of paediatricians, GPs specifically in relation to mental health concerns, and psychologists were consistently - and significantly - higher among children at risk of experiencing psychosocial adjustment issues such as hyperactivity, emotional symptoms, and conduct and peer problems across all ages.

-

Despite this, substantial proportions of children at elevated risk of experiencing poor social-emotional wellbeing and psychological adjustment were not accessing services that are more likely to specifically address these issues in children, including psychiatric and behavioural therapy services, paediatricians and psychologists.

-

Importantly, our findings also indicated a degree of unmet need for professional support or intervention among study children and their families - through both patterns found in Medicare service use as well as via parental reports. This was particularly the case for families with children with elevated risk of experiencing poor social-emotional outcomes.

Abbreviations

| ABS | Australian Bureau of Statistics |

|---|---|

| ACIR | Australian Childhood Immunisation Records |

| ACT | Australian Capital Territory |

| ADA | Australian Dental Association |

| AIFS | Australian Institute of Family Studies |

| AIHW | Australian Institute of Health and Welfare |

| AMHOCN | Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network |

| DSS | Department of Social Services |

| FSE | Full Service Equivalent |

| GP | General Practitioner |

| HIC | Health Insurance Commission |

| LOTE | Language other than English |

| LSAC | Longitudinal Study of Australian Children |

| MBS | Medicare Benefits Schedule |

| NSW | New South Wales |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PBS | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme |

| PRC | Parenting Research Centre |

| SDQ | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire |

| SEIFA | Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas |

| UK | United Kingdom |

Introduction

Delivering services that adequately and appropriately meet the needs of the community is a fundamental challenge faced by systems in Australia, including health care systems. In Australia, Medicare provides access to free or subsidised treatment by frontline health professionals such as doctors, specialists and optometrists under the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS). Medicare further provides lower-cost prescription medicine and free care to patients in public hospitals and, for vulnerable groups such as children in low-income households, the services of dentists and other allied health professionals are also subsidised.

Official data indicate that the proportion of young Australians (<25 years) accessing MBS-subsidised primary mental health care services increases with age, peaking during young adulthood (18-<25 years). Specifically, during 2014-15, around 1% of preschool-aged children (0-<5 years) had contact with MBS-subsidised primary mental health services, compared to 6% of primary school-aged children (5-<12 years), 8% of adolescents (secondary school age; i.e. 12-<18 years), and 10% of youths/young adults (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, 2016). Importantly, research indicates that poor psychological adjustment during childhood can affect future contact with the health care system; for example, over 2% of mental health-related emergency department 'occasions of service' in Australian public hospitals during 2012-13 were estimated to result from behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually in childhood and adolescence (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, 2016).

In 2016-17, Australia's total expenditure on health was estimated at $180.7 billion, equating to more than $7,400 per person (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2018). Given this, and in the context of higher rates of contact with health care services among children and adolescents experiencing - or at risk of - social and/or emotional problems (Schieve et al., 2012), early intervention and prevention initiatives may reduce both the prevalence of poor psychological adjustment among Australians over the life course and the resultant costs to the country's health care system.

Yet study findings indicate that a degree of unmet need for professional support and intervention continues to exist among Australian children. For example, a recent analysis of data from the 2013-14 Australian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing indicated that only around 12% of children aged 6-17 years with mental disorders received sufficient contact to be classified as receiving 'minimally adequate treatment' (Sawyer, Reece, Sawyer, Hiscock, & Lawrence, 2018). Among parents and carers surveyed for the Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, also during 2013-14, over one-quarter (27%) reported that their child or adolescent (aged 4-17 years) needed help for emotional or behavioural problems in the previous 12 months; however, only 17% of children and adolescents had used services for such concerns during that time (Lawrence et al., 2015). Further, using data from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) and matched Medicare data, Hiscock and colleagues (2019) found that fewer than one quarter of children identified as having a mental health problem had seen a mental health professional in the 18 months following their most recent LSAC interview.

To address unmet need, poor psychological health and the associated outcomes among Australian children, and in consideration of the substantial cost of public health care (from both consumer and provider perspectives), it is of significant policy interest to comprehensively examine the level and nature of health care service use among Australian children. This includes the identification of psychosocial and socio-economic factors predictive of service engagement. Such information could inform targeted education, prevention and referral programs with the intention of engaging 'at risk' children with suitable professional support and early intervention, and educating parents and children's various caregivers1 about effective methods of improving children's short- and long-term health, wellbeing and overall quality of life (Newman, 2012).

In this paper, data from LSAC and the MBS are used to examine children's use of certain Australian health care services, and to explore differences in the percentage of children using these services, depending on their levels of psychological adjustment, including issues such as emotional problems, conduct problems and hyperactivity.

Specifically, we sought to investigate:

- patterns of health care service use among children over time

- the socio-demographic and familial characteristics of children accessing various Australian health care services, via parents' self-report and MBS data

- whether children classified as experiencing elevated risk of developing social-emotional problems accessed health care services at greater rates than other children.

1 Diverse health service providers and support networks, such as maternal and child health nurses, hospital emergency staff, and school guidance counsellors, may also be able to provide valuable forms of early assistance, intervention or appropriate referrals for children at risk of mental health problems and their families.

Data and methodology

The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children

LSAC is undertaken in a partnership between the Department of Social Services (DSS), the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). The study follows two cohorts of children who were selected from across Australia - children in the B cohort ('babies' at Wave 1) were born between March 2003 and February 2004, and children in the K cohort ('kindergarten' at Wave 1) were born between March 1999 and February 2000.

The sampling frame for LSAC was created using the Health Insurance Commission's Medicare database, a comprehensive database of Australia's population. A stratified sample of postcodes was subsequently generated, from which a sample of children was selected, and their families invited to participate in the study. The final sample, comprising 54% of these families, was broadly representative of Australian children (Soloff, Lawrence, & Johnstone, 2005). The first wave of LSAC interviews was conducted between March 2004 and January 2005; since then, families are interviewed every two years. For a detailed description of the design of LSAC, see: Gray and Smart (2009).

In general, LSAC gathers comprehensive, nationally representative data on important aspects of a child's life, including their experiences within families and communities, child care experiences, and experiences in early education. LSAC data also provide substantial information about various aspects of children's development, including physical and mental health; motor skills; social, cognitive and emotional development; and language, literacy and numeracy. LSAC was designed with the study child as the main focus of the study. Reports from different types of respondents are sought to obtain information about the child's behaviour in different contexts. Specifically, information is collected from: the child (including physical measurements, cognitive testing and, depending on the age of the child, interviews); the parent who knows most about the child ('primary carer'); any secondary parent in the household (biological, adoptive or step-parents); home-based and centre-based carers for preschool children who are regularly in non-parental care; and teachers for school-aged children. From Wave 2, information has also been obtained from the parent who lives in a separate household than the primary carer but who still has contact with the child.

At the time of writing, data from seven main waves of the survey were available, collected in 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014 and 2016. For this paper, analyses focused on children in the LSAC B cohort, particularly on children aged between 4-5 and 12-13 years, given this was the most under-investigated group of children regarding mental health outcomes. For the B cohort, the Wave 1 sample consisted of 5,107 observations. Just over 90% of the Wave 1 sample was retained at Wave 2; in subsequent waves, over 95% of the sample completed at least one follow-up interview. The Wave 7 sample comprised 66% of the original Wave 1 sample.

Matched MBS data

Analyses of MBS data afford opportunities to supplement parental reports of their children's health service use by analysing official usage data for various service types. Data linkage with official health care system databases allows objective investigations of service use trends among LSAC children over time; for instance, such data are not biased by social desirability concerns or recall issues, as is the case with self-report information (Althubaiti, 2016).

In Wave 1 of LSAC (2004), the vast majority (97%) of all study children's parents gave consent for their children's data to be linked with comprehensive Medicare Australia information on an ongoing basis; approximately 96% of B cohort children's parents consented to the MBS data linkage (N = 4,875). Medicare Australia information includes study children's usage history details relating to the MBS, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), and Australian Childhood Immunisation Records (ACIR) services. Linkage was successful for 93% of children (incomplete consent forms resulted in data not being released for around 400 children). In consideration of this study's aims and objectives (outlined above), our analyses used only LSAC children's MBS data.

At the time of writing, records were available for MBS services accessed by study children between January 2002 (i.e. birth for the LSAC B cohort) and early 2017, resulting in a dataset comprising 502,334 observations (service visits) for the B cohort. Information in the dataset included: children's unique identification number (used to link the datasets), MBS item number and category (for service classification), date of service, date of processing, schedule fee, provider charge, out-of-pocket amount (if applicable), and benefit paid (if applicable).

A number of limitations affected the utility of MBS service use information by study children and the efficiency with which the MBS data could be analysed, including issues relating to data completeness, integrity and quality, such as data entry errors or service misclassifications (e.g. 'geriatric' classifications for services provided for children and adolescents), missing data and inconsistent variable formats. In addition, while item numbers were available to assist with the classification of all MBS service visits by study children over the data collection period, generic umbrella categories (e.g. 'management of bulkbilled services', 'other non-referred professional attendance', 'health assessments') precluded comprehensive examination of services provided, service providers' professional specialty/ies, and reasons for service use. Additionally, item numbers may become obsolete; once this occurs, they are removed from the MBS Online item number cache2 along with comprehensive details regarding their respective service classifications, fees, benefits, patient eligibility criteria, etc.).3

Measures

Parents' reports of children's use of health care services

In LSAC there are two sources of data available regarding children's use of health services. Firstly, the study child's primary carer - usually their mother - is asked whether the study child has used a range of health services in the 12 months prior to their LSAC interview at each wave. The list of health services includes:

- general practitioners (GPs)

- paediatrician

- psychiatric services or behavioural therapy

- other specialists

- speech therapy

- hospital emergency services

- hospital outpatient services

- dental services.

Children's use of health care services: MBS data

While parents' responses indicated if a health service has been used in the previous 12 months, they were not asked about how many times each type of service was accessed by study children. For some types of services, the matched MBS data can provide additional insights into frequency of service use. For the purposes of this study, the MBS service types assessed were chosen to reflect those included in the LSAC survey. The service types explored using MBS data comprised:

- four types of GP visits (note that all four GP categories are mutually exclusive):

- service provided at any location and lasted <20 minutes

- service provided at any location and lasted ≥20 minutes

- service provided after hours

- service provided was mental health-specific

- paediatrician

- psychologist

- other specialists.

For each of these services, we created indicators of whether the service had been used during the two years prior to each wave of LSAC data collection, in addition to frequency of service access. The two-year period was chosen (vs a shorter time frame, such as one year) to more comprehensively examine rates of MBS service use further to those identified in the self-report data, and in consideration of the two-year period (approximately) between each data collection wave, especially given that a shorter time frame would not capture all instances of MBS service use during that time.

To gauge unmet need for - and difficulties accessing - professional support, parents were asked if study children had needed any of these services in the past 12 months but were unable to access them.

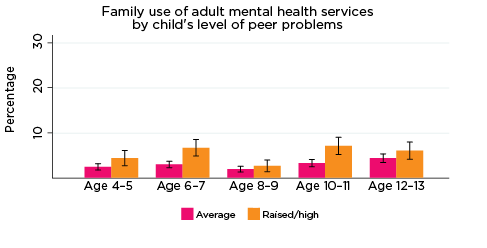

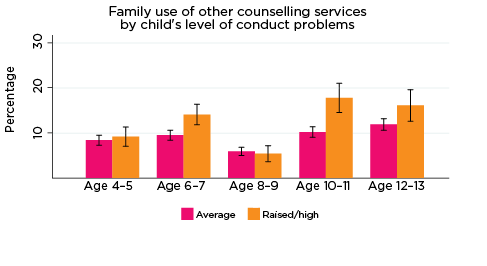

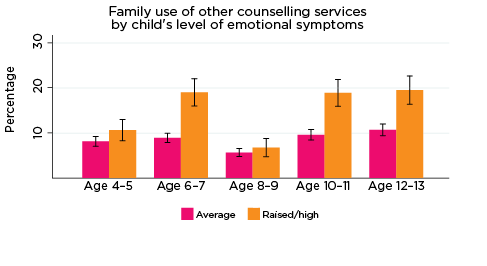

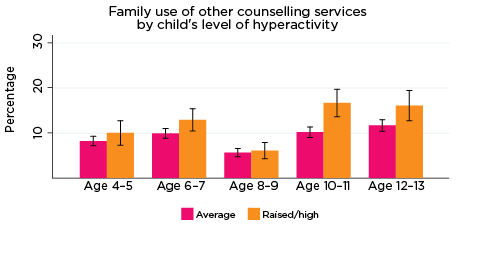

Use of mental health and support services at the household level

Further to questions about health service use by study children, parents were asked whether anyone in their household had used any of the following services in the 12 months prior to the LSAC interview:

- parenting education

- family support group

- phone or internet helpline

- adult mental health services

- relationship counselling

- other counselling

- disability services.

As in relation to health service use by the study child, to gauge unmet need for - and difficulties accessing - professional support at the household level, parents were asked if family members had needed any of these services but were unable to access them.

Measures of child and adolescent social-emotional wellbeing: The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

The social and emotional outcomes analysed in this report are based on children's scores on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). The SDQ is a brief behavioural screening questionnaire designed to measure the psychological adjustment - that is, risk of experiencing social-emotional problems - of children aged between three and 16 years. This scale has been widely implemented and evidence of its psychometric properties has been demonstrated in a large number of studies, including those using Australian data (Hawes & Dadds, 2004; Stone, Otten, Engels, Vermulst, & Janssens, 2010). It is not intended to be used as a diagnostic instrument, but rather a measure of problematic emotions and behaviours across a range, from 'normative' to 'highly elevated' (Stone et al., 2010).

The SDQ Problems Subscale consists of 20 items, some positive and others negative, where each item describes an attribute of the child's behaviour (Goodman, 1999). The 20 items are divided into four scales, each comprising five items:

- hyperactivity/inattention (e.g. is restless, overactive, cannot stay still for long)

- conduct problems (e.g. often fights with other children or bullies them)

- emotional symptoms (e.g. has many fears and is easily scared)

- peer problems (e.g. is rather solitary, tends to play alone).

The primary carer of the study child indicates whether each item is: 'not true', 'somewhat true' or 'certainly true' of the child, and responses are scored 0, 1 or 2, respectively, such that higher scores indicate more problematic behaviour. Each of the four subscales therefore has a range of 0-10, with higher scores indicating a greater risk of clinically significant problems.

The full SDQ questionnaire consists of 25 items,4 with an additional five items measuring prosocial behaviours (e.g. is considerate of other people's feelings; shares readily with other children; helpful if someone is hurt, upset or feeling ill; kind to younger children; often volunteers to help others). This scale also has a range of 0-10; however, lower scores on the prosocial scale indicate a higher risk of social problems (Goodman, 1999).

For each subscale, cut points have been derived from UK samples to indicate the presence of elevated symptom levels (Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network, 2005). For the analyses presented here, consolidated indicators of 'slightly raised' and 'high' risk are used, as the number of observations for children at high risk of significant problems was too small for reliable estimates. The percentages of boys and girls exhibiting a raised or high (hereafter: 'elevated') risk of significant problems, for each SDQ subscale, are shown in Table 1.

| SDQ component | Age 4-5 (2008) % | Age 6-7 (2010) % | Age 8-9 (2012) % | Age 10-11 (2014) % | Age 12-13 (2016) % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | |||||

| Emotional symptoms | 19.6 | 16.7 | 16.9 | 19.5 | 17.4* |

| Conduct problems | 23.1 | 28.2* | 23.0* | 18.1 | 16.2 |

| Hyperactivity | 18.3* | 24.1* | 25.4* | 23.3* | 19.9* |

| Peer problems | 23.5* | 25.1* | 25.7* | 26.6 | 27.2* |

| SDQ Total Difficulties score | 22.0 | 20.5* | 20.4* | 18.0* | 16.2 |

| Prosocial behaviour | 32.6* | 12.6* | 11.4* | 8.8* | 12.6* |

| Total, n | 1,972 | 2,173 | 2,062 | 1,888 | 1,711 |

| Girls | |||||

| Emotional symptoms | 21.8 | 18.3 | 20.0 | 22.1 | 26.1 |

| Conduct problems | 21.3 | 19.7 | 16.7 | 15.1 | 13.3 |

| Hyperactivity | 10.9 | 13.5 | 15.1 | 11.5 | 11.3 |

| Peer problems | 18.9 | 19.8 | 21.0 | 22.9 | 21.4 |

| SDQ Total Difficulties score | 16.8 | 12.9 | 14.1 | 12.9 | 14.4 |

| Prosocial behaviour | 19.3 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 4.5 | 7.9 |

| Total, n | 1,852 | 2,038 | 1,945 | 1,775 | 1,623 |

| All | |||||

| Emotional symptoms | 20.7 | 17.5 | 18.4 | 20.8 | 21.6 |

| Conduct problems | 22.2 | 24.1 | 19.9 | 16.7 | 14.8 |

| Hyperactivity | 14.7 | 18.9 | 20.4 | 17.6 | 15.7 |

| Peer problems | 21.2 | 22.5 | 23.4 | 24.8 | 24.3 |

| SDQ total score | 19.4 | 16.8 | 17.4 | 15.5 | 15.3 |

| Prosocial behaviour | 26.1 | 8.6 | 7.3 | 6.7 | 10.3 |

| Total, N | 3,824 | 4,211 | 4,007 | 3,663 | 3,334 |

Note: *Indicates a statistically significant difference (95% significance level) in percentage for boys vs girls.

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, weighted

For some subscales, the percentage of boys categorised as being at elevated risk of problems is significantly higher than that for girls. For example, across all age groups, the percentage of boys at elevated risk of problems related to hyperactivity was significantly higher for boys than for girls; at ages 6-7 and 8-9, a higher percentage of boys than girls were at risk of conduct problems; and at age 4-5, almost one third of boys, but only 20% of girls, were at risk of problems related to prosocial behaviour. At age 12-13, the percentage of girls who were at elevated risk of emotional symptoms and peer problems was significantly higher than that for boys.

Measures used in the multivariate analysis

The explanatory variables used in the multivariate analyses captured a range of characteristics known to be related to social-emotional outcomes and also with access to - and use of - health care services. These variables can be categorised into three groups:

- Characteristics of the study child - age group, gender, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, language other than English (LOTE) spoken at home, birth order, parent-reported physical health, and special health care needs.

- Characteristics of their household - parental income, receipt of income support, parents' education, parents' physical and mental health, private health insurance coverage, single or two-parent household, and whether a household member other than the study child had a physical health condition or disability.

- Characteristics of where they live - whether they resided in a major city, inner regional, outer regional or remote area, and level of economic advantage of their neighbourhood (SEIFA score).

Family-level use of services may differ depending on whether a family member has a long-term health condition or disability, and whether the household member with health difficulties was an adult or a child. Given this, for our analyses of service use by household members, the indicator of whether a household member - other than the study child - had a disability or long-term health condition was replaced by five indicators of whether the study child's mother, father, sibling, grandparent or other household member had a disability or long-term health condition.

Specific details about these measures (e.g. information on use of specific validated tools) can be found in Appendix B.

Statistical analyses

This report first provides descriptive evidence of rates of health service use by study children according to both parental reports and MBS data, followed by service use by family members. Descriptive findings are also presented for the relationship between children's social-emotional wellbeing and use of health services, for the children themselves and also for household members.

As mentioned previously, we were interested in the use of health services at the time that social-emotional difficulties were in the very early stages, when intervention would be of most benefit. For this reason, we examined children's use of health services in the 12- or 24-month period prior to the LSAC interview in which information about social-emotional problems (related to the child's behaviour in the previous six months) was collected, rather than the use of health services of children who had already been identified as being at risk of social-emotional issues. In any case, it is important to note that while the SDQ measures used refer to the child's behaviour in the six months to one year prior to their LSAC interview, the outcome measures - use of health services - refer to the period 12-24 months prior to the LSAC interview.

Multivariate analyses were used to account for a variety of factors related to both social-emotional outcomes and health service use (using both self-report and MBS data; Tables 6-8). Random effects logistic regression models were used, pooling five waves of data (Waves 3-7, corresponding with ages 4-5 to 12-13).5

For analyses of the MBS data where information was available regarding frequency of service use, random effects Poisson and negative binomial regressions were employed due to: the non-normal distribution of the study data, the capacity of these statistical approaches to estimate the relationship between 'exposure' variables (e.g. psychosocial or socio-economic factors) and outcomes when the outcome is 'count' or frequency information comprising positive (non-negative) integers (such as the number of times a study child accessed a particular service), and their ability to inform generalisations of findings to wider populations (specifically in relation to the use of random vs fixed effects). Negative binomial regression was used especially for its sensitivity in identifying significant associations when the outcome variable comprises a large number of zero values (i.e. for service types accessed relatively infrequently to others, such as psychologists vs GPs for less than 20 minutes). All analyses were conducted using Stata version 15.1.

Results

Overall use of health and support services

The percentage of children using specific medical services, as reported by parents, varied with age. For example, around 94% of children had used any of the services investigated at age 4-5, compared to approximately 89% at age 12-13 (Table 2). Overall, the most commonly accessed service among children was a GP; at least two thirds of children had accessed a GP at least once in the last 12 months at every age.

| Service | Age 4-5 (2008) % | Age 6-7 (2010) % | Age 8-9 (2012) % | Age 10-11 (2014) % | Age 12-13 (2016) % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General practitioner | 77.6 | 73.1 | 67.3 | 66.8 | 66.8 |

| Paediatrician | 8.1 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 8.6 | 6.5 |

| Other specialist | 10.8 | 11.5 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 13.9 |

| Hospital emergency | 19.0 | 14.6 | 15.8 | 16.1 | 16.9 |

| Hospital outpatient services | 6.4 | 5.9 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 7.0 |

| Psychiatric services or behavioural therapy | 2.8 | 4.5 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 7.5 |

| Guidance counsellor | 1.1 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 5.3 | 6.2 |

| Speech therapy | 12.6 | 9.4 | 5.5 | 3.5 | 2.0 |

| Dental services | 33.7 | 55.9 | 62.3 | 65.4 | 67.8 |

| Used any of the above | 93.6 | 89.9 | 89.1 | 89.9 | 89.2 |

| Needed any of the above, but could not get | 7.9 | 5.7 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Total, N | 4,385 | 4,237 | 4,048 | 3,696 | 3,299 |

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, weighted

Paediatricians specialise in the health and development of babies, teenagers and adolescents; however, referrals to a paediatrician are usually only required if a child has an ongoing or underlying health concern that needs to be monitored and treated by a specialist (these consultations often incur out-of-pocket expenses). LSAC data show that while almost 40% of children aged 0-1 year had seen a paediatrician in the previous 12 months (Warren, 2018), less than 10% of children over the age of 4-5 had visited a paediatrician in the past year.

Almost one in five 4-5 year olds had been to hospital emergency in the previous 12 months. From age 6-7, the percentage of children who had accessed hospital emergency services remained quite stable, at around 15-16%. In comparison, around 6-7% of children had used any hospital outpatient services in the previous 12 months across all age groups.

The percentage of children using speech therapy services decreased considerably with age, from 13% of 4-5 year olds to 2% of 12-13 year olds. This decline could be considered unsurprising given that, with appropriate treatment (especially at an early age), many speech and language difficulties can be resolved (Law, Zeng, Lindsay, & Beecham, 2012).

Conversely, the percentage of children who had used psychiatric services or behavioural therapy increased with age - from 3% of 4-5 year olds to 7.5% of 12-13 year olds. Use of guidance counsellors also increased as children got older - from 1% of children at age 4-5 to 6% at age 12-13. The increase after age 6-7 is likely because guidance counsellors are mainly school counsellors; in addition to providing course and career guidance for secondary students, guidance counsellors in primary schools mainly encourage school attendance and provide information about, and referrals to, other support agencies for children who may benefit from these services.

The Australian Dental Association (ADA) recommends that children should initially see a dentist when their first tooth becomes visible, and subsequently have dental check-ups every six months (ADA, 2016). Given these recommendations, the proportion of children who had seen a dentist in the previous 12 months was lower than would be expected at each time point, even in the teenage years and despite an increase in the rate of dentist access over the study period. Specifically, only 34% of 4-5 year olds had been to a dentist in the previous 12 months, compared to 56% of 6-7 year olds and 68% of 12-13 year olds.

Difficulties accessing health services

Visits to medical practitioners in the early years of childhood depend mainly on the physical and mental health of the child and the need for specific health services. Difficulties accessing services are likely to be related to a variety of factors, including location and availability of services (particularly in regional and remote areas), as well as knowledge of services and how to navigate complicated systems and referral processes. For some, concerns about confidentiality and poor previous experiences with health practitioners may be barriers to accessing services (Cummings & Kang, 2012). In addition, appointments with medical practitioners such as paediatricians, dentists and other specialists can involve considerable out-of-pocket expenses. It is therefore likely that visits to such service providers also depend, at least partly, on household income and whether the family is covered by private health insurance.

As indicated in Table 2, although most parents reported no difficulties with access to health services for their child in the past 12 months, 8% reported problems accessing health services when their child was aged 4-5. For parents of children aged eight and older, the percentage reporting difficulties with service access reduced to around 4%.

Using LSAC data, Warren (2018) found that difficulties accessing health services were more common among families in regional and remote areas than for those living in metropolitan areas. This finding is consistent with research from the AIHW (2017), which showed that people living in remote and very remote areas generally have poorer access to - and less frequently engage with - health services than people in regional areas and major cities.

LSAC findings also provide evidence of difficulties related to the cost of health services, with families in the lowest quartile of equivalised income, and those without private health insurance, more likely to report trouble accessing services. Language difficulties and knowledge about how to access services also appeared to be a factor; among families with young children, those who spoke a LOTE were more likely to have reported difficulties accessing health services (Warren, 2018).

Overall use of MBS services

Table 3 lists the percentages of LSAC study children who had used each of the MBS service types assessed in our analyses at least once in the two years prior to interview during Waves 3-7 of data collection. The service type children most commonly engaged with during this time period was a GP for 20 minutes or less. Although the percentage of children accessing this service decreased at each subsequent wave, it remained above 80% throughout the whole study period. This finding generally accords with the self-report data regarding GP use in Table 2 above; specifically, that GPs were the most commonly accessed service among study children, according to parental reports; however, the MBS data provide more context regarding the types of service commonly provided by GPs.

Also reflecting a finding identified in Table 2: the percentages of children accessing a paediatrician at each wave were stable-decreasing as children got older. The MBS figures are notably higher than the parental report data in Table 2, which is likely due to differences in service use rates during the past year (parental data) versus past two years (MBS).

The after-hour services of GPs were used by a substantial minority of the cohort throughout the follow-up period, ranging from nearly one third (31.4%) at age 4-5, to close to one quarter (22.9%) at age 12-13. In contrast to these decreasing rates, and corresponding with the LSAC cohort's increasing age, the percentages of children accessing psychologists and GPs for mental health-specific concerns rose as children got older.

| Service | Age 4-5 (2008) % | Age 6-7 (2010) % | Age 8-9 (2012) % | Age 10-11 (2014) % | Age 12-13 (2016) % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General practitioner | |||||

| 1. <20 minutes | 92.3 | 88.4 | 85.3 | 82.0 | 80.3 |

| 2. ≥20 minutes | 20.6 | 13.4 | 14.6 | 18.4 | 23.4 |

| 3. Mental health-specific concerns | 0.8 | 3.1 | 6.1 | 8.0 | 9.5 |

| 4. After hours | 31.4 | 27.2 | 25.2 | 22.5 | 22.9 |

| Paediatrician | 14.0 | 12.6 | 14.5 | 13.3 | 12.3 |

| Psychologist | 0.8 | 2.9 | 5.2 | 7.4 | 7.9 |

| Other specialist | 16.3 | 16.0 | 12.9 | 11.7 | 12.2 |

| Use of any service | 93.9 | 90.4 | 88.3 | 86.2 | 84.6 |

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, and MBS data, years 2008-16

The figures listed in Table 4 detail the average number of visits to each MBS service type (and range) by children's age. Reflecting high usage rates of GPs for less than 20 minutes, this service type was also the most frequently visited by study children at each age, ranging from a mean of 7.0 at 4-5 years to 4.5 at ages 10-11 and 12-13. In contrast, the utilisation frequency of other GP service options (i.e. 20 or more minutes, for mental health-specific concerns and after hours) appeared to remain relatively stable across the follow-up period. Overall, the average frequency of visiting any service type decreased slightly between ages 4-5 and 12-13, from 8.6 to 6.6, respectively.6

| Service | Mean frequency and range | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 4-5 (2008) | Age 6-7 (2010) | Age 8-9 (2012) | Age 10-11 (2014) | Age 12-13 (2016) | |

| General practitioner | |||||

| 1. <20 minutes | 7.0 (1-48) | 5.7 (1-48) | 4.9 (1-49) | 4.5 (1-47) | 4.5 (1-38) |

| 2. ≥20 minutes | 1.5 (1-12) | 1.4 (1-18) | 1.4 (1-7) | 1.5 (1-12) | 1.5 (1-11) |

| 3. Mental health-specific concerns | 1.3 (1-3) | 1.3 (1-5) | 1.4 (1-6) | 1.4 (1-5) | 1.6 (1-14) |

| 4. After hours | 1.9 (1-19) | 1.9 (1-19) | 1.8 (1-27) | 1.6 (1-13) | 1.7 (1-12) |

| Paediatrician | 2.5 (1-33) | 2.8 (1-30) | 2.9 (1-44) | 2.9 (1-31) | 3.1 (1-30) |

| Psychologist | 4.3 (1-17) | 4.4 (1-18) | 5.9 (1-31) | 5.8 (1-28) | 5.5 (1-20) |

| Other specialist | 4.3 (1-17) | 2.1 (1-27) | 2.0 (1-15) | 1.7 (1-9) | 2.0 (1-15) |

| Use of any service | 8.6 (1-69) | 7.3 (1-60) | 6.7 (1-56) | 6.3 (1-60) | 6.6 (1-71) |

Note: Means and ranges calculated for children who engaged with services during each two-year period prior to interviews (i.e. zero values were excluded).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, and MBS data, years 2008-16

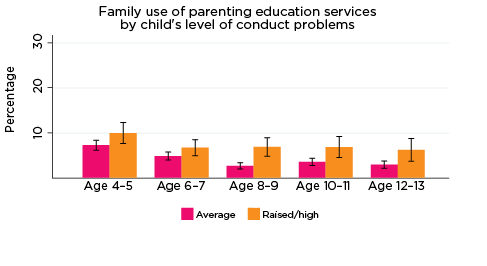

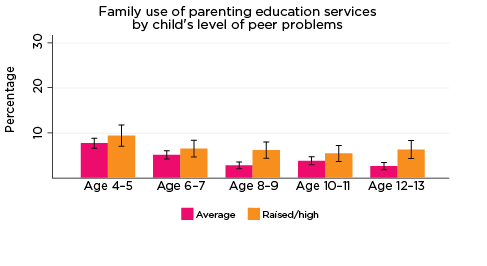

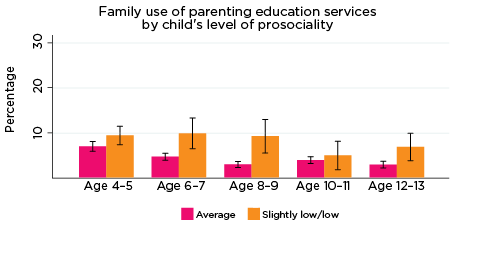

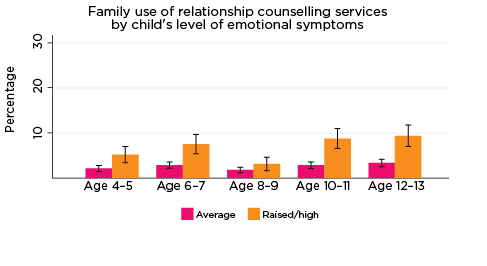

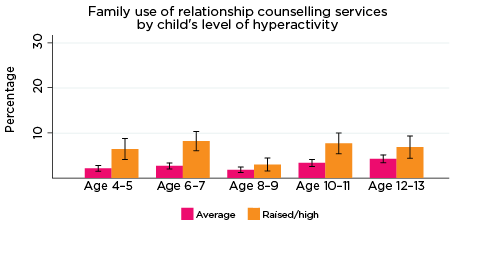

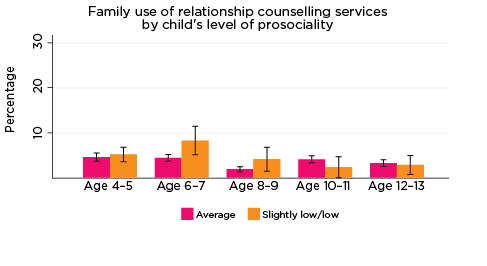

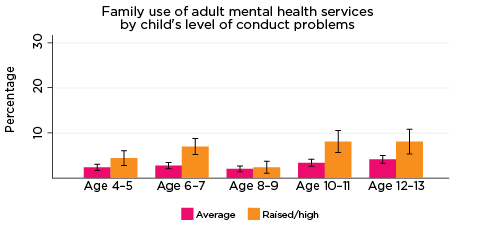

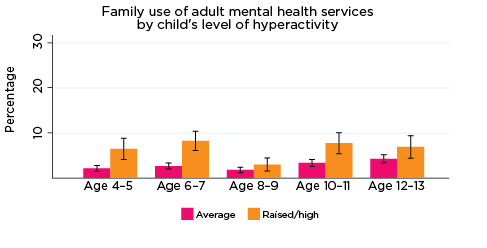

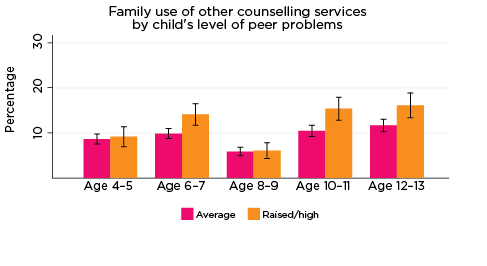

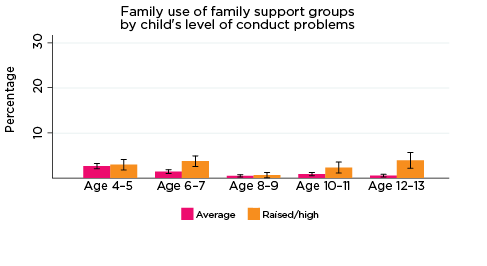

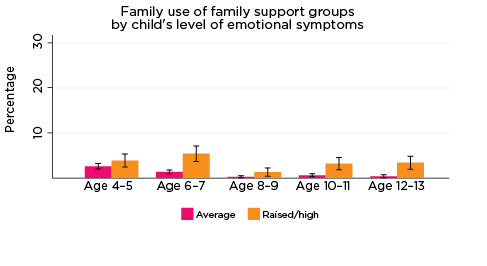

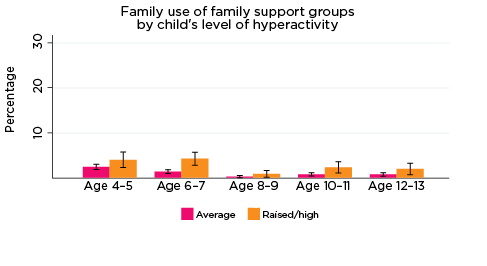

Use of counselling and support services at the family level

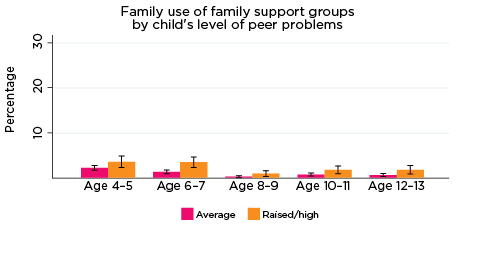

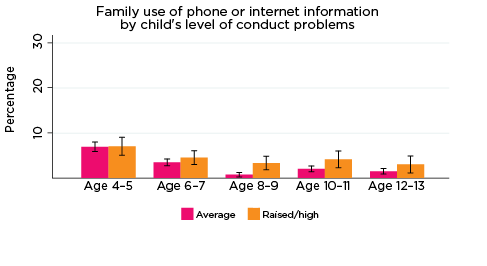

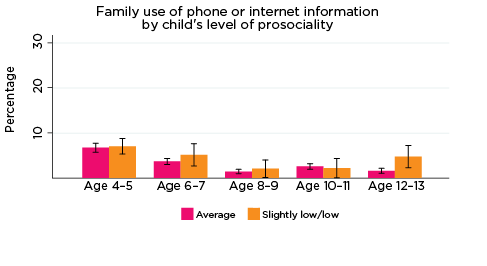

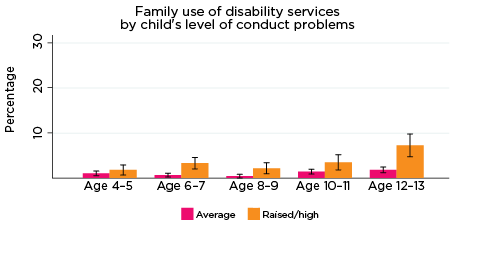

As was the case for children's use of health services, use of professional support options such as parenting education, family support groups, counselling and other mental health services at the household level depends on the need for these services; that is, whether any household members have physical or mental health issues that require these services. Across all age groups, around one quarter of parents reported using some type of support service for a family member, with 'Other counselling' being the most commonly reported service used (Table 5).

| Service | Age 4-5 (2008) % | Age 6-7 (2010) % | Age 8-9 (2012) % | Age 10-11 (2014) % | Age 12-13 (2016) % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting education | 7.6 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 3.9 |

| Family support group | 2.9 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Phone or internet helpline | 6.7 | 4.3 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| Adult mental health services | 3.5 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 5.2 |

| Relationship counselling | 4.9 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 3.4 |

| Other counselling | 8.9 | 10.9 | 6.4 | 11.6 | 12.6 |

| Disability services | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 3.2 |

| Used any of the above | 26.6 | 23.7 | 18.4 | 23.4 | 23.4 |

| Needed any of the above, but could not get | 3.4 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.2 |

| Total, N | 4,385 | 4,237 | 4,048 | 3,696 | 3,299 |

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, weighted

The percentages of families who had used services such as parenting education and phone or internet helplines decreased with the age of the study child, while for other services, such as adult mental health services and other counselling, levels of use increased slightly as the study children got older. Notably, very few parents reported difficulties accessing these services; this suggests that, for most families, support for emotional issues is available when needed.

Parents' reports of children's use of health services, by social-emotional outcomes

Across all age groups, there were significant - and often substantial - differences in children's use of a range of health services as per parental reports, according to whether or not they had an elevated (i.e. raised or high) risk of social-emotional problems. These differences are described below for each of the SDQ subscales of emotional symptoms, hyperactivity, conduct problems, peer problems and pro-social behaviour.7

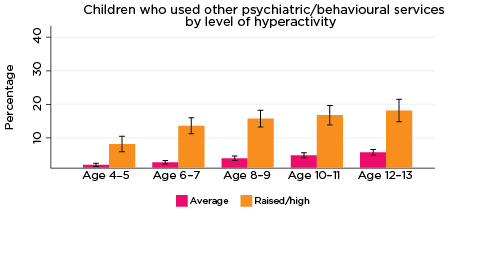

Psychiatric or behavioural therapy services

For all five SDQ subscales and across all age groups (4-5 to 12-13), the percentage of children who used psychiatric or behavioural therapy services in the previous 12 months was significantly higher among those with higher levels of social-emotional problems (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Use of psychiatric or behavioral therapy services, by social-emotional outcomes

Notes: Use of service in the last 12 months. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,823 (age 4-5), 4,206 (age 6-7), 3,998 (age 8-9), 3,656 (age 10-11), 3,271 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, weighted

In addition, the percentage of children who had been to psychiatric or behavioural therapy services increased substantially with age. For example:

- Among children with elevated levels of emotional symptoms, the percentage of children who had used psychiatric or behavioural therapy services increased from 6% at age 4-5 to 22% at age 12-13. In contrast, among children with lower levels of emotional symptoms, the percentage who had used psychiatric or behavioural therapy services increased from 2% at age 4-5 to 4% at age 12-13.

- Among children with elevated levels of peer problems, the percentage who had used psychiatric or behavioural therapy services increased from 7% at age 4-5 to 17% at age 12-13. For children with lower levels of peer problems, the percentage who had used psychiatric or behavioural therapy services increased from 2% at age 4-5 to 4% at age 12-13.

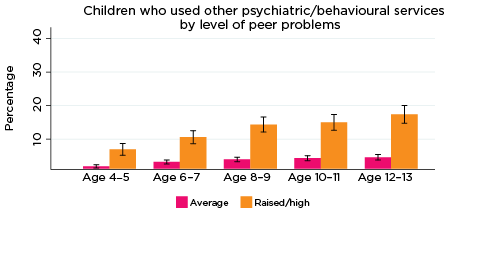

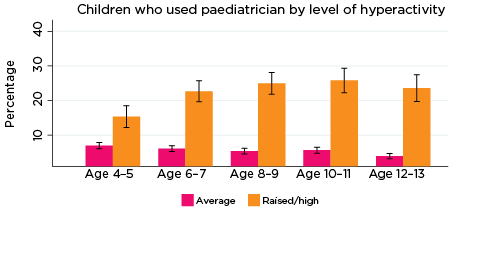

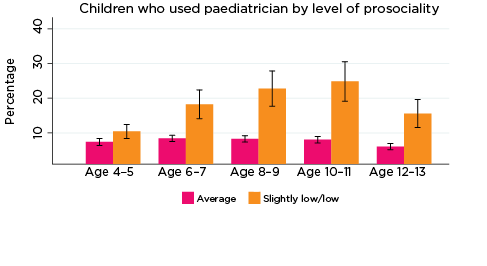

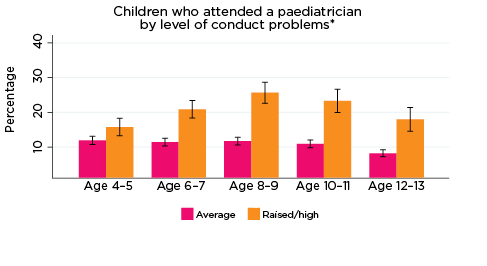

Paediatrician

As was the case for psychiatric and behavioural therapy services, the percentage of children who had a consultation with a paediatrician in the previous 12 months was significantly higher among those with elevated levels of social-emotional problems across all age groups and for all five SDQ subscales (Figure 2). The only exception was for prosocial behaviour at age 4-5.

Differences in the percentages of children who had seen a paediatrician, according to whether there was a risk of social-emotional problems, were substantial, ranging from three percentage points for those with elevated levels of conduct problems at age 4-5 (10% compared to 7%), to 19 percentage points for those with elevated levels of hyperactivity at age 10-11 (24% vs 5%).

Figure 2: Use of paediatricians, by social-emotional outcomes

Notes: Use of paediatrician in the last 12 months. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,823 (age 4-5), 4,206 (age 6-7), 3,998 (age 8-9), 3,656 (age 10-11), 3,271 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, weighted

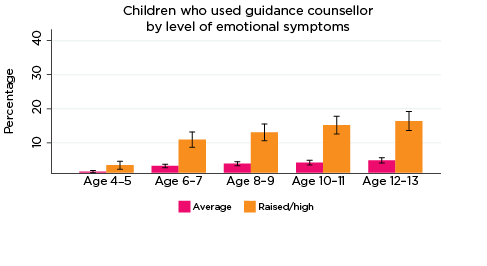

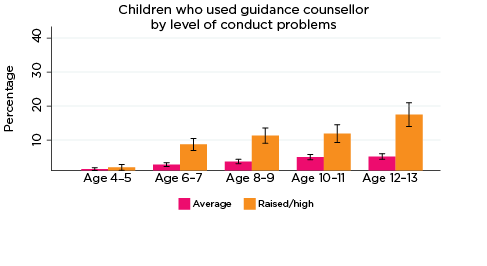

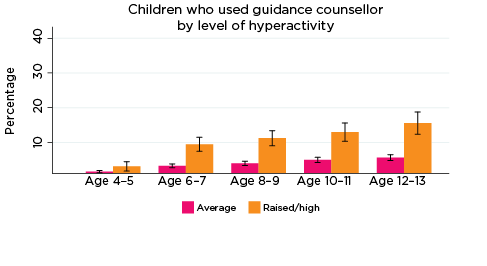

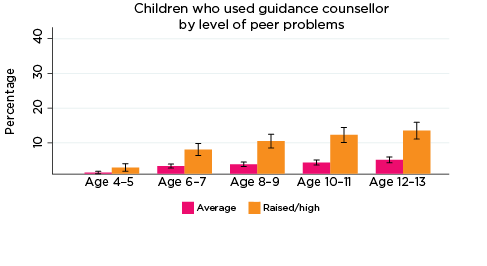

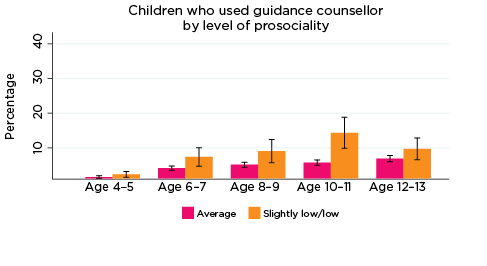

Guidance counsellor

The percentage of children who had used guidance counsellor services in the previous 12 months was significantly higher among those with elevated levels of emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity and peer problems from ages 6-7 to 12-13, and also among children with lower levels of prosocial behaviour at ages 8-9 and 10-11 (Figure 3). For example:

- Among children with elevated levels of emotional symptoms at age 6-7, 10% had used guidance counsellor services in the past 12 months, compared to 2% of children with lower levels of emotional symptoms.

- Among those with elevated levels of conduct problems at age 12-13, 16% had used guidance counsellor services, compared to 5% for other 12-13 year olds.

- Among adolescents with lower levels of prosocial behaviour at age 10-11, 13% had used guidance counsellor services in the previous 12 months, compared to 5% of other children aged 10-11.

Figure 3: Use of guidance counsellor services, by social-emotional outcomes

Notes: Use of guidance counsellor in the last 12 months. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,823 (age 4-5), 4,206 (age 6-7), 3,998 (age 8-9), 3,656 (age 10-11), 3,271 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, weighted

The lack of statistical significance regarding the percentage of children who had used guidance counsellor services at age 4-5 is likely because guidance counsellors are usually a service provided at school, and the number of parents reporting that their children had used this service at age 4-5 was very small.

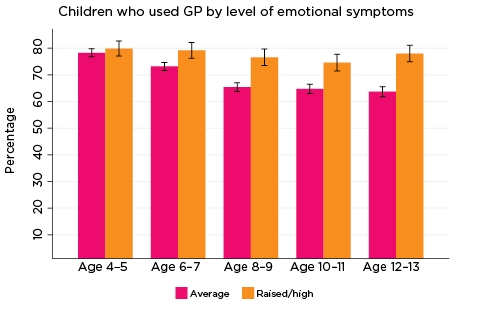

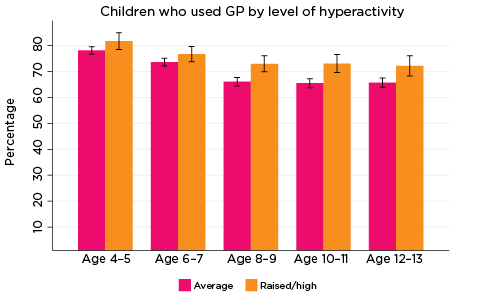

General practitioner

The percentage of children whose parents reported at least one consultation with a GP in the previous 12 months was significantly higher among those with elevated levels of:

- emotional symptoms from ages 6-7 to 12-13. This difference increased with age. At age 6-7, 79% of children with elevated levels of emotional symptoms had seen a GP in the past 12 months, compared to 73% of other children. At age 12-13, 78% of those with elevated levels of emotional symptoms had seen a GP, compared to 64% of other children (Figure 4).

- hyperactivity at ages 8-9, 10-11 and 12-13. Across these three age groups, almost three quarters (72-73%) of children with increased risk of problems related to hyperactivity had been to a GP in the past 12 months, compared to around two thirds of other children in these age groups.

- peer problems at ages 10-11 and 12-13. Among those with elevated levels of peer problems at ages 10-11 and 12-13, the percentage who had seen a GP in the past 12 months was 74% and 71%, respectively, compared to around 66% of other children at both ages.

Figure 4: Use of GP services, by social-emotional outcomes

Notes: Use of general practitioner in the last 12 months. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,823 (age 4-5), 4,206 (age 6-7), 3,998 (age 8-9), 3,656 (age 10-11), 3,271 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, weighted

Across all age groups, there were no significant differences in the percentage of children who had used GP services in the previous 12 months, according to their levels of conduct problems or prosocial behaviour.

Emergency department

The percentage of children who had been to a hospital emergency department in the previous 12 months was significantly higher among those with elevated levels of:

- emotional symptoms at 6-7, 8-9 and 12-13. At ages 6-7 and 8-9, one in five (20%) of children with increased levels of emotional symptoms had been to emergency, compared to 14-15% of other children. At age 12-13 the difference was larger, with 23% for children with elevated levels of emotional symptoms having been to emergency, compared to 15% for children with lower levels (Figure 5).

- conduct problems at ages 4-5, 8-9 and 12-13. At age 4-5, almost one quarter (24%) of children with elevated levels of conduct problems had been to emergency, compared to one in five (19%) of other children. At age 12-13, the difference was larger, with one in four adolescents with elevated risk of conduct problems having been to emergency in the past 12 months, compared to around one in six (16%) of other children.

- hyperactivity at ages 4-5, 6-7 and 8-9. At age 4-5, one in four children with elevated levels of hyperactivity had been to the emergency department, compared to one in five (21%) children with lower levels of hyperactivity. At ages 6-7 and 8-9, the difference was larger, with 21% of children with elevated levels of hyperactivity having been to emergency, compared to 15% of other children.

- peer problems at ages 6-7 and 8-9. Around 20% of children with an increased risk of peer problems had been to the emergency department at ages 6-7 and 8-9, compared to 14% of other children in these age groups.

Figure 5: Use of emergency department, by social-emotional outcomes

Notes: Emergency attendance in the last 12 months. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,823 (age 4-5), 4,206 (age 6-7), 3,998 (age 8-9), 3,656 (age 10-11), 3,271 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, weighted

Across all age groups, there were no significant differences in the percentage of children who had been to the emergency department in the previous 12 months, according to their level of prosocial behaviour.

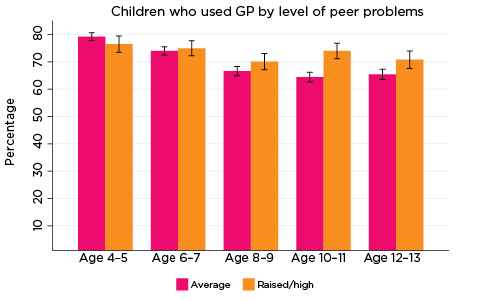

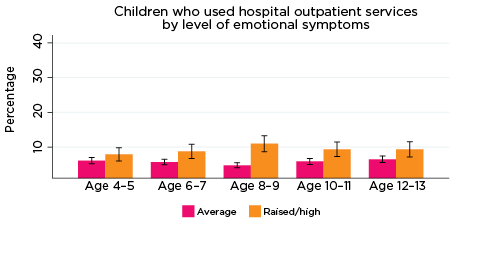

Hospital outpatient services

The percentage of children who had accessed hospital outpatient services in the previous 12 months was significantly higher among those with elevated levels of:

- emotional symptoms at ages 6-7, 8-9 and 10-11. Among children with elevated levels of emotional symptoms, 9-11% had been to hospital outpatient services, compared to 5-6% of children with lower levels of emotional symptoms (Figure 6).

- conduct problems, at age 8-9 only. Among those with elevated levels of conduct problems at age 8-9, 10% had accessed hospital outpatient services, compared to 5% for other children aged 8-9.

- hyperactivity at ages 6-7 and 8-9. At both ages, 11% of children with elevated levels of hyperactivity had been to hospital outpatient services, compared to 5% of other children.

- peer problems at ages 4-5, 6-7 and 8-9. For children in these three age groups, 9% of those with elevated levels of peer problems had accessed hospital outpatient services in the past 12 months, compared to 5-6% of children with lower levels of peer problems.

Figure 6: Use of hospital outpatient services, by social-emotional outcomes

Notes: Use of outpatient services in the last 12 months. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,823 (age 4-5), 4,206 (age 6-7), 3,998 (age 8-9), 3,656 (age 10-11), 3,271 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, weighted

At age 10-11, but not at other ages, the percentage of children who had accessed hospital outpatient services in the previous 12 months was significantly higher among those with lower levels of prosocial behaviour (12% compared to 5% for children with higher levels of prosocial behaviour).

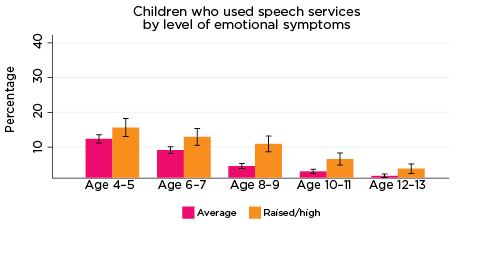

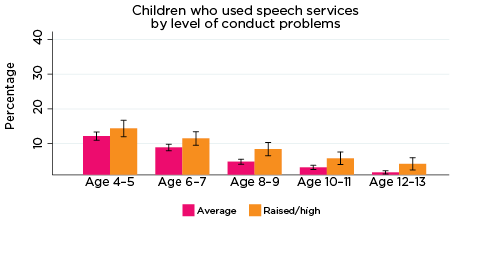

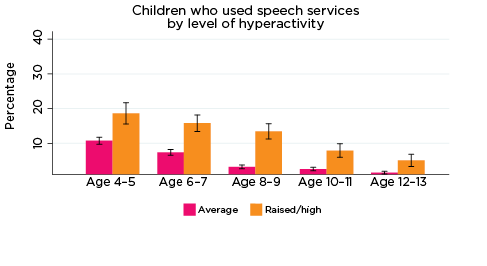

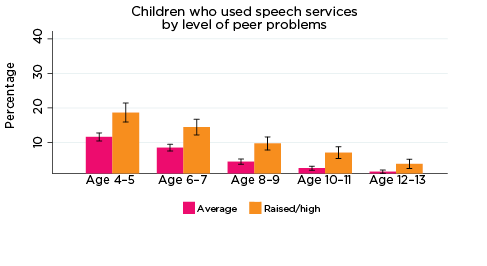

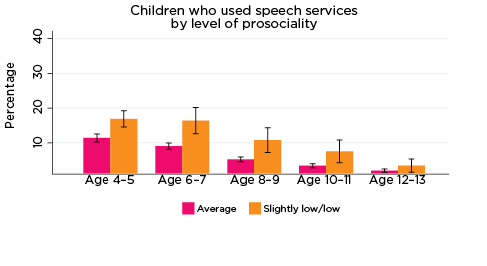

Speech therapy

The percentage of children who had been to a speech therapist in the previous 12 months declined considerably with age - from 13% of 4-5 year olds to 4% of 10-11 year olds and 2% of 12-13 year olds. However, there were still significant differences in the percentage of study children who had used this service, according to their social-emotional outcomes. For example, among children with elevated levels of hyperactivity, the percentage of children who had been to a speech therapist decreased from 20% for 4-5 year olds to 5% for 12-13 year olds. For children with lower levels of hyperactivity, the percentage of children who had used speech therapy services was 12% at age 4-5, and 1% at age 12-13 (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Use of speech therapy services, by social-emotional outcomes

Notes: Speech service use in the last 12 months. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,823 (age 4-5), 4,206 (age 6-7), 3,998 (age 8-9), 3,656 (age 10-11), 3,271 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, weighted

These results suggest that, at least for some children, poor social-emotional outcomes may be related to a physical health condition or disability, such as hearing loss. Indeed, research has demonstrated that speech and hearing difficulties may lead to poorer social-emotional outcomes among children (as measured by the SDQ) (Stevenson, Kreppner, Pimperton, Worsfold, & Kennedy, 2015). Therefore, the use of specific health services may not necessarily be to treat the emotional symptoms, but emotional symptoms may be related to difficulties arising from the health condition requiring medical treatment.

Dental services

The percentage of children who had been to the dentist in the previous 12 months was significantly lower among those with elevated levels of:

- conduct problems and hyperactivity at age 8-9. Among those with elevated levels of conduct problems or hyperactivity at age 8-9, 58% had been to the dentist, compared to 64% for other children aged 8-9 (Figure 8).

- peer problems at ages 4-5, 8-9, 10-11 and 12-13. For example, at age 12-13, 59% of those with elevated levels of peer problems had been to the dentist, compared to 71% of other children aged 12-13.

Figure 8: Use of dental services, by social-emotional outcomes

Notes: Dental service use in the last 12 months. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,823 (age 4-5), 4,206 (age 6-7), 3,998 (age 8-9), 3,656 (age 10-11), 3,271 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, weighted

At age 8-9, but not at other ages, the percentage of children who had been to the dentist in the previous 12 months was significantly reduced among those with lower levels of prosocial behaviour (55% compared to 63% for children with higher levels of prosocial behaviour).

It is possible that children with hyperactivity, conduct problems or lower levels of prosocial skills are more difficult to take to the dentist, or that dental services are less of a priority for parents when children have issues that require ongoing medical treatments. Indeed, research has shown that dental care is one of the most commonly cited unmet health concerns for children with other health care needs (Lewis, 2009).

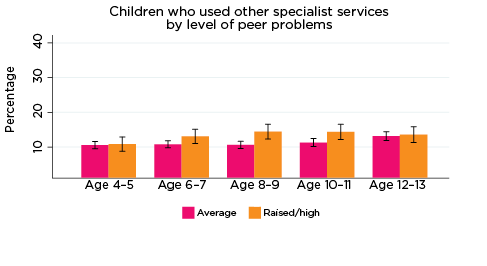

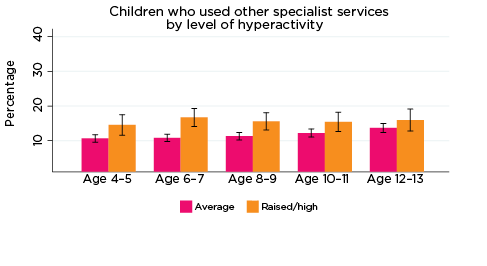

Other specialists

The percentage of children who had used other specialist services in the previous 12 months was significantly higher among those with elevated levels of:

- hyperactivity at ages 6-7 and 8-9. Among children in these two age groups, 16-17% of those with elevated levels of hyperactivity used other specialists in the past 12 months, compared to 11% for other children aged 6-7 and 8-9.

- peer problems at age 8-9 only. Among children with elevated levels of peer problems at age 8-9, 15% had used other specialist services, compared to 11% of children with lower levels of peer problems at that age (Figure 9).

Across all age groups, there were no significant differences in the percentage of children who had used other specialist services in the previous 12 months, according to their level of emotional symptoms, conduct problems or prosocial behaviour. This lack of statistical significance may be because 'other specialists' covers a broad range of services, some of which are related to social-emotional problems, while others are not.

Figure 9: Use of other specialist services, by social-emotional outcomes

Notes: Use of service in the last 12 months. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,823 (age 4-5), 4,206 (age 6-7), 3,998 (age 8-9), 3,656 (age 10-11), 3,271 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, weighted

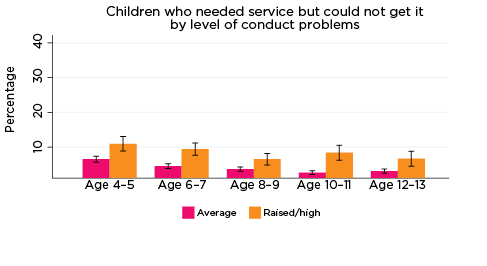

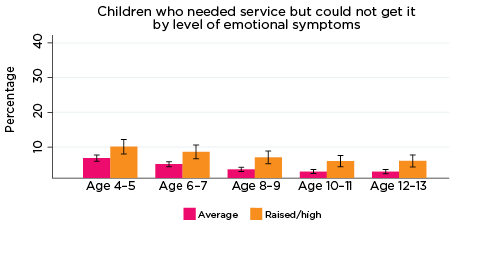

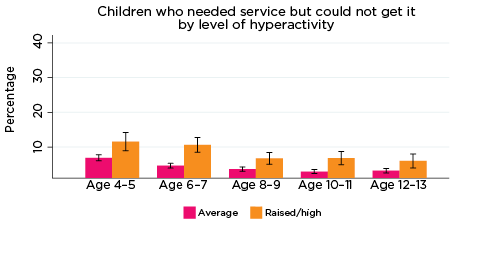

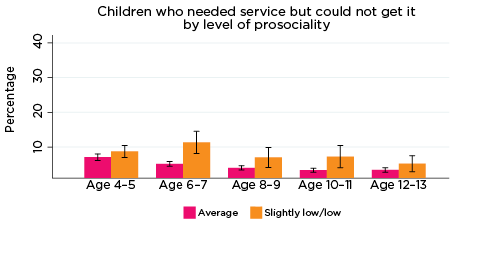

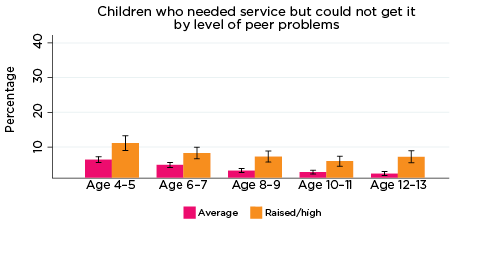

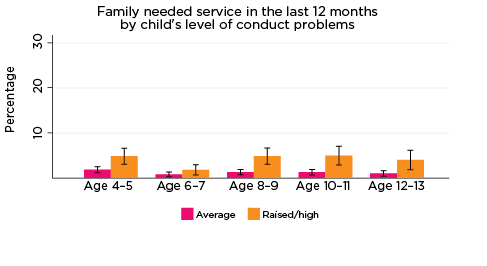

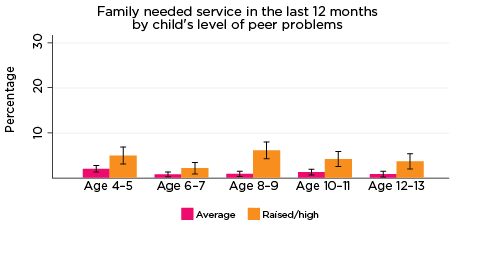

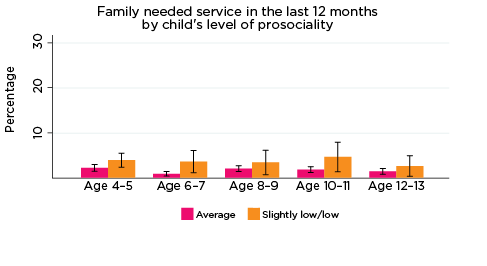

Access to health services

The percentage of parents who reported that they had needed health services for their child in the previous 12 months, but were not able to get them, was significantly higher among parents whose children had elevated levels of risk of social-emotional problems. For example, among parents of children with elevated levels of risk of conduct problems at all ages, the percentage who reported experiencing difficulties accessing services ranged from 11% when their children were aged 4-5, to 7% when children were aged 12-13. Among parents of children with a lower risk of conduct problems, the percentage reporting difficulties accessing services ranged from 7% when their children were aged 4-5, to 3% when their children were aged 10-11 and 12-13 (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Difficulties accessing health services, by social-emotional outcomes

Notes: Needed service in the last 12 months. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,823 (age 4-5), 4,206 (age 6-7), 3,998 (age 8-9), 3,656 (age 10-11), 3,271 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort, weighted

Children's use of MBS services, by social-emotional outcomes

This section details children's use of various MBS services - GPs, psychologists, paediatricians and specialists - as per the linked Medicare data. Each figure in this section indicates children's use of services in the two years prior to their/their parents' interview at each LSAC wave with respect to rankings on each of the SDQ subscales of emotional symptoms, hyperactivity, conduct problems, peer problems and pro-social behaviour.

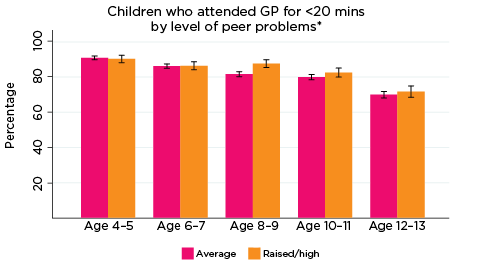

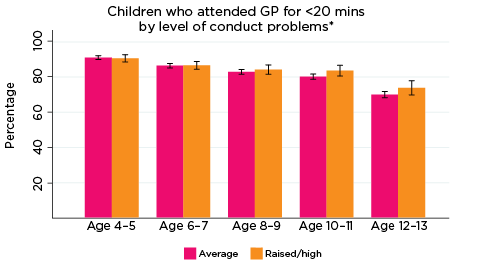

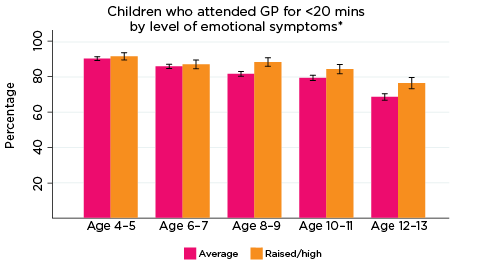

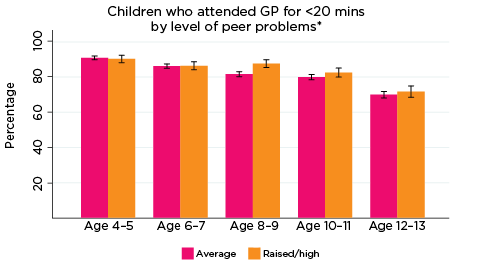

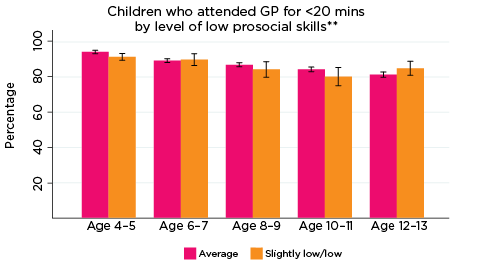

GP for less than 20 minutes

The most commonly used service type among LSAC children overall was a GP for less than 20 minutes. As demonstrated in Figure 11, regardless of the level or type of psychological adjustment symptom, use of GPs for less than 20 minutes tended to decrease as children got older; at age 4-5, around 92% of children had accessed a GP for less than 20 minutes in the two years prior to interview, compared to approximately 80% at age 12-13. Perhaps due - in part - to the high rate of use of this type of service (i.e. given the small numbers of children not in contact with GPs for less than 20 minutes), there were very few significant differences among children regarding use of GP services for less than 20 minutes in relation to level/type of psychological symptom measured by the SDQ. One exception was in relation to the level of emotional symptoms: at ages 8-9 and 12-13, a significantly higher number of children with elevated risk of experiencing emotional symptoms had accessed a GP for less than 20 minutes in the two years prior to interview, compared to those with average risk (90% vs 84% and 84% vs 79%, respectively).

Figure 11: Use of GPs for less than 20 minutes, by psychological adjustment symptoms and age

Notes: * GP attendance corresponding with years of data collection; i.e. 2008/09-2016/17. ** Service attendance during two years prior to each interview. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,693 (age 4-5), 4,060 (age 6-7), 3,881 (age 8-9), 3,539 (age 10-11), 3,281 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort and MBS data, weighted

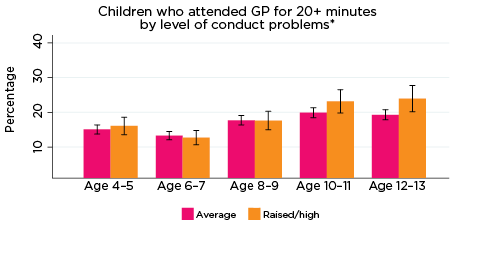

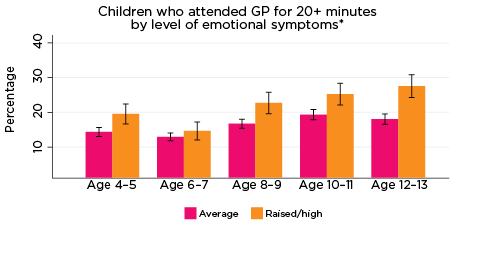

GP for 20 minutes or longer

The use of GP services for 20 or more minutes typically decreased between the ages of 4-5 and 6-7 years, before increasing over the remainder of the data collection period (Figure 12). Increasing rates of use following the age of 6-7 appeared to be influenced largely by children at elevated risk of experiencing emotional symptoms, hyperactivity and peer problems. There were numerous significant differences among the cohort in relation to these indicators of psychological adjustment; for example, at age 12-13, 29% of children at elevated risk of experiencing peer problems had accessed a GP for ≥20 minutes in the past two years, compared to 22% of those with average risk. In contrast, there were no significant differences in rates of use of GP services for 20 or more minutes with regard to levels of risk of experiencing conduct problems or having low prosocial skills.

Figure 12: Use of GPs ≥20 minutes, by psychological adjustment symptoms and age

Notes: * GP attendance corresponding with years of data collection; i.e. 2008/09-2016/17. ** Service attendance during two years prior to each interview. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,693 (age 4-5), 4,060 (age 6-7), 3,881 (age 8-9), 3,539 (age 10-11), 3,281 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort and MBS data, weighted

GP for mental health concerns

Use of GP services specifically for mental health concerns tended to increase steadily as children got older (Figure 13). There were significant differences in the use of GPs for mental health concerns in the past two years in relation to levels of risk of poor psychological adjustment, specifically with regard to risk of experiencing emotional symptoms, conduct and peer problems, and hyperactivity. For example, at age 10-11, approximately 16% of children with elevated risk of experiencing conduct problems had accessed a GP for mental health concerns in the past two years, compared to around 7% of children experiencing only average risk. Similarly, at the same age, 16% of children with elevated risk of experiencing hyperactivity had accessed a GP specifically in relation to mental health, compared to 8% of those with only average risk of hyperactivity. In contrast, children at elevated risk of experiencing low pro-social skills used GPs for mental health concerns at significantly higher rates than those with average risk at ages 6-7, 10-11 and 12-13, but not at ages 4-5 or 8-9. Nevertheless, overall, these findings indicate that experiencing poor psychological adjustment as young as age 4-5 years can affect rates of service use among Australian children.

Figure 13: Use of GP services for mental health concerns, by psychological adjustment and age

Notes: * GP (mental health) utilisation corresponding with years of data collection; i.e. 2008/09-2016/17.

** Service attendance during two years prior to each interview. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,693 (age 4-5), 4,060 (age 6-7), 3,881 (age 8-9), 3,539 (age 10-11), 3,281 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort and MBS data, weighted

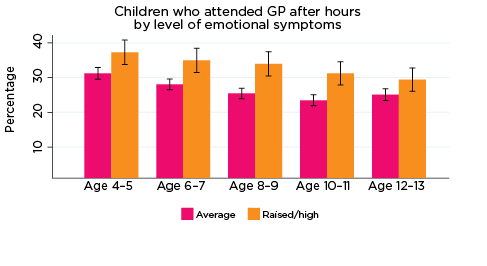

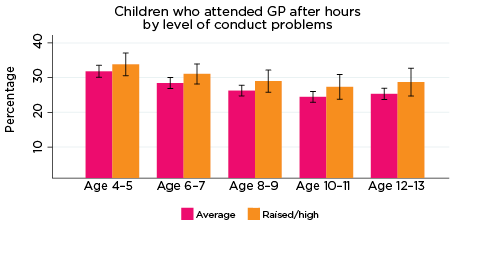

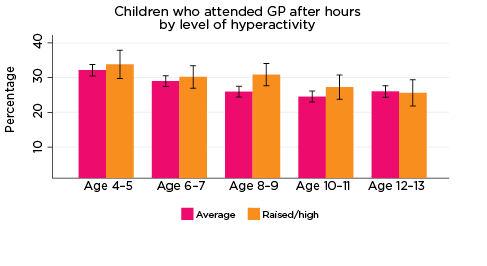

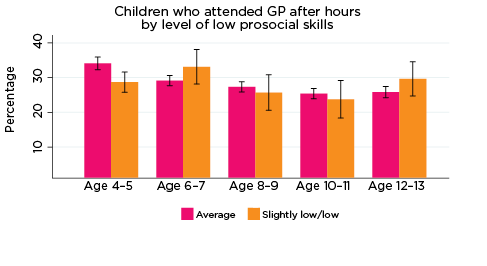

After-hours GP services

Overall, usage rates of after-hours GP services decreased slightly as children got older (Figure 14). One exception to this was in relation to level of prosocial skills; rates of using after-hours GP services were somewhat inconsistent among children with elevated risk of experiencing low prosocial skills in particular - 28% of this group had accessed a GP after hours at age 4-5, followed by 33% at age 6-7, 25% at 8-9, 23% at 10-11, and 30% at 12-13 years.

Regarding the remaining SDQ indicators of psychological adjustment, children at elevated risk of experiencing emotional symptoms were consistently significantly more likely to have accessed a GP after hours between the ages of 4-5 and 10-11 compared to children with only average risk of experiencing emotional symptoms; however, the difference between the groups was not significant at age 12-13. Few other significant differences were observed; however, children at elevated risk of experiencing peer problems were significantly more likely to have used after-hours GP services at ages 8-9 and 10-11, compared to children with only average risk of peer problems.

Figure 14: Use of after-hours GP services, by psychological adjustment and age

Notes: Service attendance during two years prior to each interview. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,693 (age 4-5), 4,060 (age 6-7), 3,881 (age 8-9), 3,539 (age 10-11), 3,281 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort and MBS data, weighted

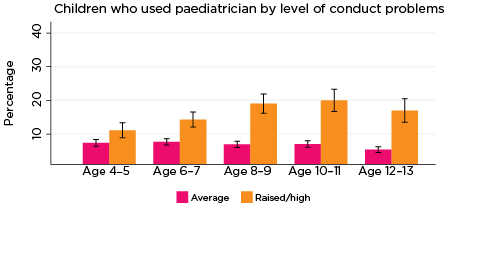

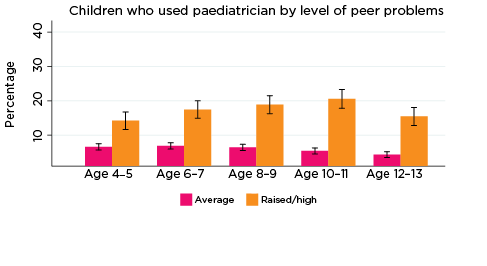

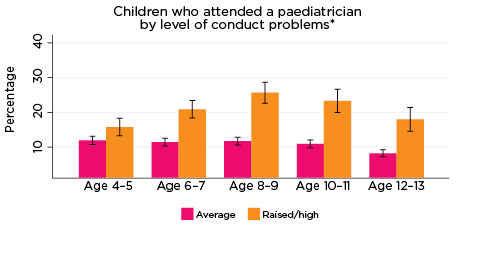

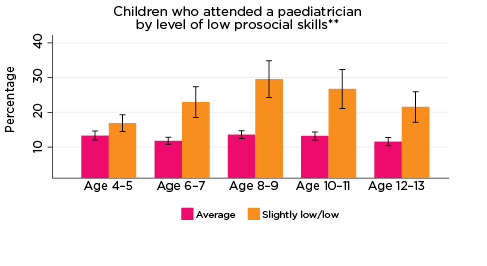

Paediatrician

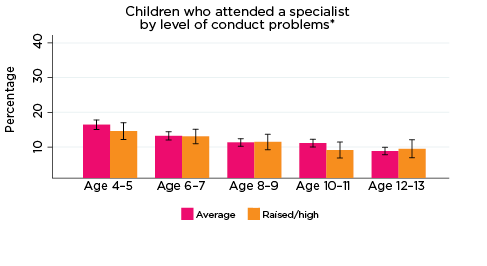

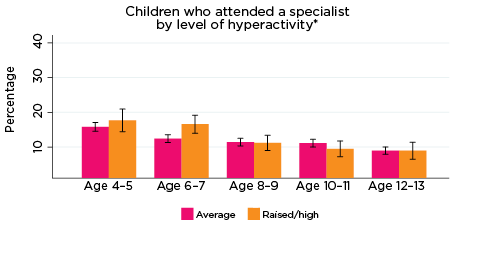

Reflecting the self-report findings above, there were distinct patterns observed among the MBS data with regard to study children's access to paediatricians (Figure 15). Notably, regardless of the type of psychological adjustment indicator, among those at elevated risk of experiencing emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems or low prosocial skills, the use of paediatricians typically increased from age 4-5 and peaked at age 8-9 years, before decreasing for the remainder of the data collection period. Conversely, among children with only average risk of experiencing any of the SDQ indicators of psychological adjustment, rates of access to paediatricians typically remained stable-decreasing over time. In accord with these opposing trends, there were significant differences between the rates of paediatrician access among children at elevated risk of poor psychological adjustment across all indicators and age-groups, barring low prosocial skills at age 4-5.

Figure 15: Use of paediatricians, by psychological adjustment and age

Notes: * Paediatrician corresponding with years of data collection; i.e. 2008/09-2016/17. ** Service attendance during two years prior to each interview. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,693 (age 4-5), 4,060 (age 6-7), 3,881 (age 8-9), 3,539 (age 10-11), 3,281 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort and MBS data, weighted

Psychologists

Psychologist services were typically accessed at lower rates compared to the other MBS service types investigated for this study (Figure 16). Regardless, across the SDQ 'Problem' indicators, children at elevated risk of experiencing emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity or peer problems were typically significantly more likely to have accessed a psychologist in the prior two years, compared to children with just average risk of experiencing these issues. For example, at age 10-11, around 20% of children at elevated risk of experiencing emotional problems had accessed a psychologist in the last two years, compared to only 4% of children with average risk of emotional problems.

Rates of use of psychologists among children at elevated risk of emotional symptoms, hyperactivity and peer problems appeared to follow a similar pattern, increasing between the ages of 4-5, peaking at age 10-11, then decreasing at age 12-13. In contrast, among children at risk of experiencing low prosocial skills, the peak utilisation rate of psychologist services occurred at age 12-13. Among children at elevated risk of conduct problems, the rate of use of psychologists increased until age 8-9 and remained relatively stable following then.

Significant differences were observed between the percentages of children at elevated risk of experiencing emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity and peer problems across all ages, compared to those with only average risk levels. Children at elevated risk of experiencing low prosocial skills had accessed psychologists at significantly greater rates at ages 6-7, 8-9 and 12-13.

Figure 16: Use of psychologist services, by psychological adjustment and age

Notes: * Psychologist utilisation corresponding with years of data collection; i.e. 2008/09-2016/17. ** Service attendance during two years prior to each interview. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,693 (age 4-5), 4,060 (age 6-7), 3,881 (age 8-9), 3,539 (age 10-11), 3,281 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort and MBS data, weighted

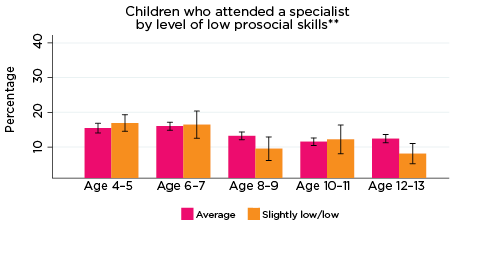

Specialists

In general, the use of specialist services typically decreased as children got older (Figure 17). Although a greater percentage of children with elevated risk of experiencing any of the SDQ indicators of poor psychological adjustment more frequently accessed specialists compared to those with average risk, there were few significant differences between the groups. Exceptions included children at elevated risk of experiencing emotional symptoms at age 12-13 (approximately 12% vs 8%, respectively), and children at elevated risk of experiencing hyperactivity at age 6-7 (17% vs 12%, respectively). The relatively low rates of specialist use compared to other service types investigated here, especially GPs, is possibly a reflection of barriers to health care types such as specialists, including cost and navigating complex referral systems.

Figure 17: Use of specialist services, by psychological adjustment and age

Notes: * Specialist utilisation corresponding with years of data collection; i.e. 2008/09-2016/17. ** Service attendance during two years prior to each interview. 95% confidence intervals are shown by 'I' bars in each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. N = 3,693 (age 4-5), 4,060 (age 6-7), 3,881 (age 8-9), 3,539 (age 10-11), 3,281 (age 12-13).

Source: LSAC Waves 3-7, B cohort and MBS data, weighted

Summary

Among children with an increased risk of social-emotional problems or poor psychological adjustment, such as emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems and poor social skills, levels of use of a range of health services were often significantly higher than for children with lower - i.e. 'normative' - risk of adverse social-emotional outcomes. For example, across all age groups and all SDQ subscales, the use of psychiatric and behavioural therapy services was significantly higher among those with elevated risk of problems. Nevertheless, among this group, only around 20% - one in five - had used psychiatric and behavioural therapy services in the previous 12 months.

Although this is likely because, for many children and adolescents in the 'raised or high' risk of problems category, they are not at a stage where they require these types of services, it is possible that some children at risk of adverse social-emotional outcomes are experiencing unmet need. Indeed, the percentage of parents who reported that they had needed health services for their child in the previous 12 months, but were unable to get them, was significantly higher among those whose children had elevated levels of risk of social-emotional problems.

Apart from psychiatric and behavioural therapy services, children at increased risk of social-emotional problems had higher rates of contact with other medical professionals including GPs, paediatricians and speech therapists, as well as hospital emergency and outpatient services. Importantly, this suggests there is an opportunity for such medical professionals to identify children who may be at risk of mental health problems at an early stage and to provide parents with advice or referrals to practitioners and services that may prevent these issues from becoming more serious.

Regarding MBS data, the utilisation rates of three distinct service types were consistently - and significantly - higher among children at risk of experiencing poor psychological adjustment or social-emotional issues: paediatricians, GPs specifically for mental health concerns, and psychologists. Although usage rates over time differed for these services (e.g. use of paediatricians tended to peak among 'at risk' children around the age of 8-9 years, whereas rates of accessing GPs for mental health concerns gradually increased among this group as children got older, likely due to the 'appropriateness' or applicability of service types as children mature), these findings provide a strong indication of the impact of experiencing psychological adjustment issues on children, their families and service providers.

In contrast to the above findings, there were minimal differences between children experiencing elevated risk of social-emotional problems and other children across all age groups in relation to accessing specialists and GPs for less than 20 minutes. The latter finding is possibly a result of the high utilisation rate of GP services for less than 20 minutes among study children in general - it was the most commonly and frequently accessed service type by far (see Appendix C for more detailed findings regarding frequency of MBS service use by risk of social-emotional outcomes).

Multivariate analysis - Children's use of health services

While the previous section demonstrated that children who are at increased risk of social-emotional issues are often more likely to use a range of health services, it should be noted that these relationships are not 'causal'. It may be the case that some children with raised levels of social-emotional problems may also be experiencing other health problems that require use of these health services. For some children with ongoing health conditions or disabilities, these conditions may themselves lead to lower levels of social-emotional wellbeing. This is likely to be the case for peer problems in particular. For example, if a child is being bullied due to physical limitations or appearance, this can lead to social-emotional issues.

Table 6 details the findings of multivariate analyses investigating associations with service use and controlling for characteristics of the child and their family that have been shown to be related to health service use (e.g. the child's physical health). Overall, findings indicated that children with increased risk of social-emotional problems had significantly higher odds of service use in the past 12 months.8

| Odds ratio | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paediatrician | General practitioner | Psychiatric services | Other specialist | Hospital emergency | Guidance counsellor | Hospital outpatient | Speech therapy | Dental | |

| Emotional symptoms | 1.51*** | 1.37*** | 3.29*** | 0.92 | 1.08 | 2.65*** | 1.14 | 1.20 | 1.03 |

| Hyperactivity | 2.81*** | 1.08 | 2.03*** | 1.24** | 1.16* | 1.77*** | 1.15 | 2.13*** | 1.01 |

| Conduct problems | 1.08 | 0.92 | 1.72*** | 0.88 | 1.11 | 1.68*** | 0.98 | 0.88 | 0.97 |

| Peer problems | 1.88*** | 1.02 | 2.02*** | 1.07 | 1.05 | 1.51*** | 1.09 | 1.49*** | 0.80*** |

| Low prosocial skills | 1.19 | 0.96 | 1.55*** | 1.24* | 0.96 | 0.84 | 1.02 | 1.17 | 0.93 |

| Age group (ref. = Age 4-5) | |||||||||

| Age 6-7 | 1.00 | 0.71*** | 2.00*** | 1.10 | 0.66*** | 3.33*** | 0.91 | 0.54*** | 3.03*** |

| Age 8-9 | 0.78* | 0.48*** | 2.40*** | 1.15 | 0.73*** | 4.10*** | 0.87 | 0.21*** | 4.03*** |

| Age 10-11 | 0.74* | 0.40*** | 2.90*** | 1.19* | 0.77*** | 4.87*** | 0.96 | 0.11*** | 4.71*** |

| Age 12-13 | 0.48*** | 0.41*** | 3.18*** | 1.39*** | 0.84* | 5.71*** | 1.08 | 0.05*** | 5.09*** |

| Boys | 1.36** | 0.93 | 1.30** | 0.96 | 1.16** | 1.04 | 1.10 | 2.29*** | 0.84*** |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 1.60 | 0.94 | 0.53 | 1.08 | 0.68* | 0.65 | 1.03 | 0.80 | 0.79 |

| LOTE | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.45*** | 0.78* | 0.77* | 0.55** | 0.68* | 0.50** | 0.80* |

| Birth order (ref. = Oldest child) | |||||||||

| Middle child/Twin | 0.76* | 0.68*** | 0.70** | 0.97 | 1.02 | 0.86 | 1.04 | 1.32 | 1.00 |

| Youngest child | 0.74** | 0.74*** | 0.71** | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 1.01 | 1.34* | 1.04 |

| Only child | 0.79 | 1.17 | 0.92 | 0.83 | 1.11 | 0.74 | 1.14 | 0.93 | 0.89 |

| Region of residence (ref. = Major city) | |||||||||

| Inner regional | 1.14 | 0.67*** | 1.11 | 0.95 | 1.20** | 1.18 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.91 |

| Outer regional or remote | 0.74 | 0.57*** | 0.69* | 0.81* | 1.22* | 0.96 | 1.18 | 0.61** | 1.07 |

| Neighbourhood advantage (ref. = Lowest 25%) | |||||||||

| Middle 50% | 0.93 | 1.13* | 1.32* | 1.16 | 0.91 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 1.07 |

| Top 25% | 0.88 | 1.17 | 1.26 | 1.06 | 0.87 | 1.19 | 0.79 | 0.91 | 1.28*** |

| Parents' education (ref. = Year 12 or below) | |||||||||

| Certificate or diploma | 1.57** | 1.27** | 1.41 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 0.84 | 1.41* | 0.99 | 1.05 |

| Degree | 1.60** | 1.16 | 1.49* | 1.27* | 1.00 | 0.84 | 1.18 | 1.04 | 1.16 |

| Private health insurance | 1.14 | 1.27*** | 1.15 | 1.43*** | 0.98 | 1.15 | 0.88 | 1.21 | 1.61*** |

| Study child in fair or poor health | 2.20*** | 1.50* | 1.10 | 2.20*** | 2.14*** | 0.41 | 2.70*** | 1.79* | 1.14 |

| Special health care needs | 11.73*** | 3.22*** | 4.84*** | 3.05*** | 1.67*** | 2.27*** | 3.50*** | 4.16*** | 1.05 |

| Parental income (ref. = Lowest 25%) | |||||||||

| 2nd | 1.17 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.03 | 0.63** | 0.94 | 1.40* | 1.01 |

| 3rd | 1.20 | 1.29** | 1.14 | 1.10 | 1.12 | 0.76 | 0.90 | 1.22 | 1.18* |

| 4th (Top 25%) | 1.42* | 1.18* | 1.27 | 1.28* | 1.22* | 0.80 | 1.02 | 1.08 | 1.21* |

| Income support | 1.18 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 1.65* | 0.97 |

| Mother poor mental health | 1.11 | 1.24** | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.23** | 1.56*** | 1.16 | 1.08 | 0.96 |

| Father poor mental health | 1.03 | 0.93 | 1.51* | 0.71* | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.27 | 0.94 | 0.88 |

| Mother poor physical health | 1.32* | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.07 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 0.99 | 1.29 | 0.90 |

| Father poor physical health | 0.92 | 1.02 | 0.89 | 1.03 | 1.16 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 1.11 |

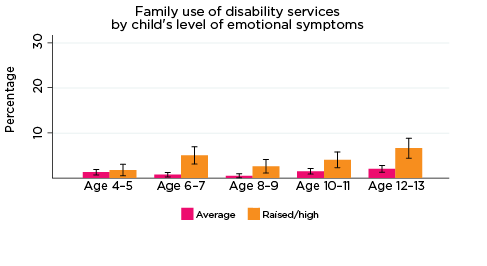

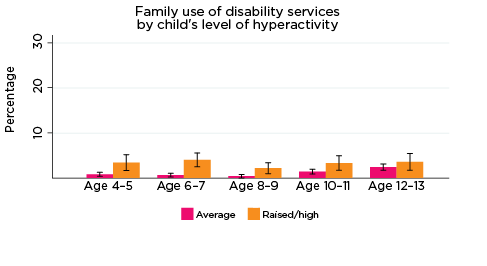

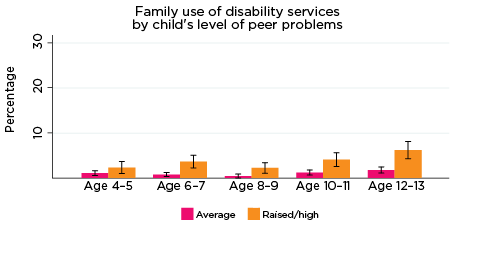

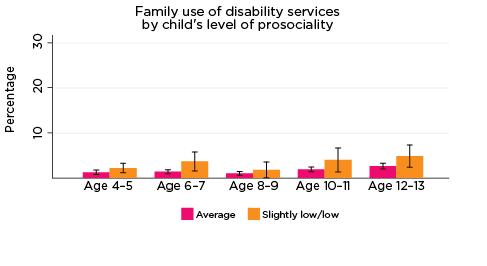

| Single-parent household | 1.07 | 0.94 | 1.83*** | 1.02 | 1.07 | 2.61*** | 1.13 | 0.74 | 1.09 |