Additional Child Care Subsidy

June 2023

Download Research snapshot

Overview

This snapshot presents key findings on Additional Child Care Subsidy (ACCS) from the 2018–2021 evaluation of the Australian Government's Child Care Package.

ACCS provides additional fee assistance to support vulnerable or disadvantaged children and families. It is a top-up payment to the Child Care Subsidy (CSS) targeted at families facing specific barriers to accessing care.1 More information about access to ACCS is available on the Department of Education (DE) website.

The analysis presented here is based on child care administrative data, interviews and surveys with parents, early childhood education and care (ECEC) services, providers and other stakeholders. Data relate to experiences up until December 2019.

Children supported by ACCS

Numbers using ACCS

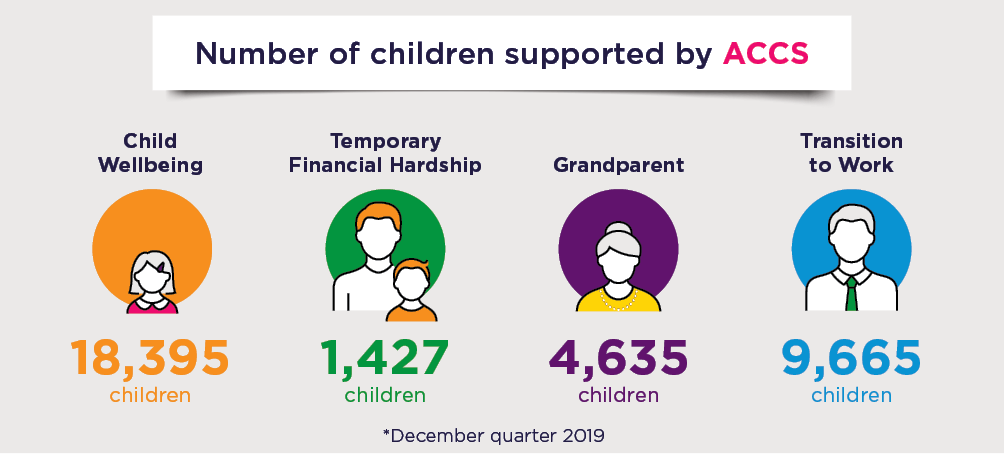

Between July 2018 and December 2019 almost 63,000 children received ACCS. In this period, since the start of the Child Care Package, the numbers grew, with 34,100 children receiving ACCS at some time in the December quarter 2019 (see Figure 1). Given the temporary nature of ACCS, the number of children supported by this subsidy varies from week to week.

There are 4 different types of ACCS:

ACCS (Child Wellbeing) supports access to approved child care for children who are at risk of serious abuse or neglect.2 This was the most common type of ACCS accessed, growing considerably between July 2018 and December 2019 from 9,404 children on ACCS (Child Wellbeing) at some time in the September quarter 2018 through to 18,395 children in the December quarter 2019.

ACCS (Child Wellbeing) is applied for by providers on behalf of families, whereas the other 3 payment types need to be applied for by individuals directly via Services Australia.

ACCS (Temporary Financial Hardship) provides short-term increased child care fee assistance to families who are experiencing significant financial stress due to exceptional circumstances and which is impacting their ability to pay for child care. This might include being adversely affected by a major disaster, the death of a partner or losing employment, for example. In the December quarter 2019, 1,427 children accessed ACCS (Temporary Financial Hardship).

ACCS (Grandparent) supports grandparent primary carers on income support.3 In the December quarter 2019, 4,635 children were supported by this payment.

ACCS (Transition to Work) supports parents who are transitioning from income support to work by engaging in work, study or training activities. In the December quarter 2019, 9,665 children were supported by this payment.

Figure 1: Numbers of children accessing ACCS each month, by type of ACCS, July 2018 to December 2019

Note: Numbers for September 2018 may not match published DESE reports due to the backdating of applications reflected in the data used by AIFS.

Source: DESE administrative data

Family characteristics of children using ACCS

As ACCS is targeted at improving access for vulnerable families, children supported by ACCS have some family characteristics that differ to those who are not supported by it. There are also some different characteristics by ACCS program component. This is shown in Figure 2 using 2018-19 data for some child and family characteristics. Significant differences were apparent for children from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, children from low-income households, children in single-parent households and children living in areas of greater socio-economic disadvantage.

For example:

- Of children who are not supported by ACCS, 20% live with a single parent.

- Of children who are supported by ACCS, 70% live with a single parent.

- The percentage living with a single parent is highest for children supported by ACCS (Transition to Work) (85%).

Figure 2: Characteristics of children who used ACCS by program component, compared to those who did not use ACCS, 2018-19

Notes: Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander status is as identified in the DESE data, DESE Indigenous flag. SEIFA is based on SEIFA 2016 Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage based on service location. Negative incomes are included in the <$66,958 category.

Source: DESE administrative data

How care is accessed with ACCS

Care type and ACCS

There was a marked difference in the distribution of ACCS support across service types. Among all children using an In Home Care (IHC) service, one-fifth (21%) accessed ACCS, which is much higher than for other care types (3.7% for Centre Based Day Care (CBDC), 2.3% for Family Day Care (FDC) and 1.6% for Outside School Hours Care (OSHC)). The higher proportion for IHC is not surprising given that one of the grounds for access to this care is the child being in a family with challenging or complex needs.

As a distribution of children supported by ACCS in 2018-19, 70% were in CBDC, 21% in OSHC, 8% in FDC and 1.5% in IHC.

ACCS and ECEC cost and use

For all but ACCS (Transition to Work), the ACCS subsidy is equal to the fee charged (up to 120% of the hourly rate cap) for up to 100 hours per fortnight, without an activity test. For ACCS (Transition to Work) the subsidy is 95% of the fee charged (up to 95% of the hourly rate cap), with the activity level determining the number of hours of subsidised care.4 Given these differences, out-of-pocket costs for ECEC vary depending on the type of ACCS.

Considering fortnightly child care costs for children on ACCS at some time in the December 2019 quarter, but excluding those in IHC, the average net child care cost while on ACCS was zero for 67% of those in receipt of the subsidy. For those with a non-zero cost, the average was $40.98 per fortnight. However, this varied by the type of ACCS.

While children on ACCS can have up to 100 hours per fortnight of subsidised child care, many used less than this. Of those on ACCS (Child Wellbeing), 25% used 1-36 hours per fortnight, 32% used 37-72 hours per fortnight, and 40% used 73-100 hours per fortnight. Very few (3%) used more than 100 hours.5

Service characteristics and ACCS

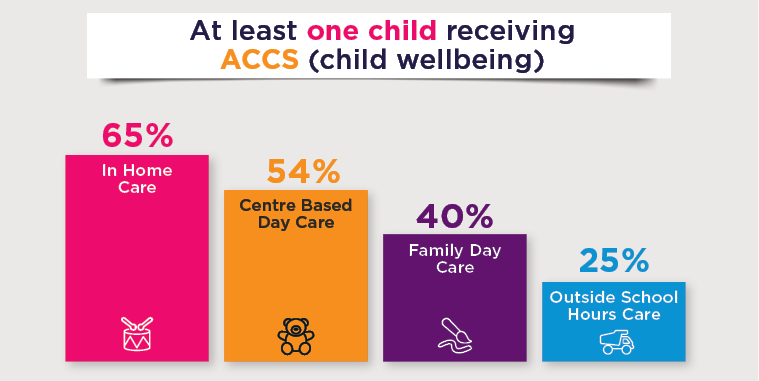

Of the 13,776 ECEC services across Australia between July 2018 and December 2019, 5,953 (43%) had at least one child on ACCS (Child Wellbeing) at some time during the financial year.6

The percentage of services with children on ACCS (Child Wellbeing) varied by care type of the service:

- 65% of IHC and 54% of CBDC services had at least one child receiving ACCS (child wellbeing), compared to 40% of FDC services and only 25% of OSHC services.

The percentage increased with service size:

- from 26% of services with less than 50 children attending to 63% of services with at least 200 children attending.

The percentage varied by area and was highest in regional areas:

- inner regional and outer regional areas (51% and 48% respectively), compared to 42% in major cities, 25% in remote areas and 18% in very remote areas.

Operational aspects of ACCS

This section highlights some of the evaluation findings about the operational aspects of the ACCS, drawing on data from services and stakeholders, as well as additional survey and administrative data analysis. The focus is predominantly on ACCS (Child Wellbeing) but also considers ACCS (Temporary Financial Hardship).

ACCS (Child Wellbeing)

Gaps in coverage

Some services reported that they experienced difficulties providing uninterrupted access to ACCS to children, in part due to the requirement to apply for a determination for ACCS (Child Wellbeing) beyond the first 6-week certificate that can be granted by services.

- Analysis of administrative data showed that some children experienced gaps in ACCS (Child Wellbeing) coverage, particularly in the immediate period after the first 6 weeks covered by the certificate if a determination was not in place. This had financial implications for families when their child care costs increased significantly in the period not covered by ACCS.

Another issue raised was that gaining access to support of ACCS (Child Wellbeing) may be delayed if families had not yet applied for or been approved for CCS.

Talking to families and making referrals

Providers are encouraged to talk to families about ACCS and its purpose if they identify a child may be eligible. Services are required to refer the families of children on ACCS (Child Wellbeing) to an appropriate support agency. In the evaluation survey, many services agreed that staff were confident in talking to families about ACCS (Child Wellbeing) applications (53% agreed or strongly agreed) and in knowing how to refer families to appropriate organisations (54% agreed or strongly agreed).

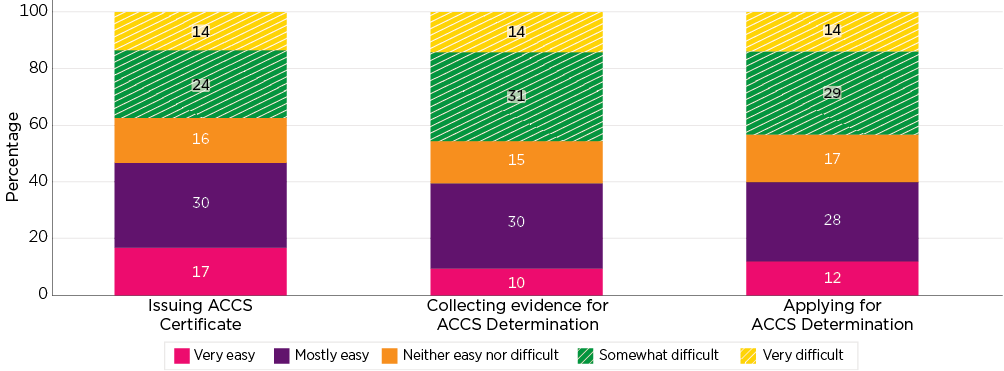

Collecting evidence for certificates and determinations

To grant a certificate for ACCS (Child Wellbeing) and to then apply to Services Australia for a determination for another 13 weeks, services need to gather appropriate documentation to support the claim that the child is at risk. Service responses about the ease of the various ACCS processes are shown in Figure 3. Overall:

- Responses were more positive with regard to issuing certificates.

- The balance was towards the negative for collecting evidence and in applying for determinations, although a significant proportion reported these tasks were very or mostly easy.

Figure 3: Services, ease of ACCS (Child Wellbeing) operations, June 2019

Notes: Excludes 'Not applicable'/'Don't know'/'Prefer not to say' responses.

Source: Survey of Early Learning and Care Services, July-August 2019

Examples of difficulties experienced were provided in qualitative data collections. These included:

- External organisations were slow to respond to requests for evidence.

- There were difficulties resolving issues if an application was rejected.

- There were problems applying for ACCS for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were informally in the care of a relative.

Identifying children at risk

Additional challenges included the need for services to identify that a child might meet the eligibility criteria for being at risk of abuse or neglect. Some problems identified by services and stakeholders were:

- The threshold for risk in the guidelines was seen as too high and meant children from families that they considered to be highly disadvantaged and vulnerable were unable to access adequate amounts of care.

- There was concern that using the language 'at risk' raised fears for Indigenous families, particularly around their children being removed, often raising past traumas surrounding the Stolen Generations and other welfare practices.

- It was reported that discussions about ACCS between child care staff and parents could be fraught in that, for some communities, family difficulties were not seen as 'child care business'.

ACCS (Temporary Financial Hardship)

After ACCS (Child Wellbeing), the ACCS type discussed most by services in interviews and in comments in surveys was ACCS (Temporary Financial Hardship). In contrast to previous arrangements where applications for this type of assistance could be made by services on behalf of families, under ACCS it is based on a family application to Centrelink.

Divergent perspectives were given by services on this change. A few services reported they saw the value of families applying through Centrelink, as this removed the responsibility for assessment from services. However, other services reported that it reduced accessibility. There were several reasons services cited for this: Centrelink staff were poorly informed about the ACCS types and provided families with incorrect information; generally, Centrelink was seen as being inaccessible for families, particularly families with English as an additional language. A number of services further commented that placing the onus on families to do additional paperwork in a time of crisis was unrealistic, and under the previous system services were able to undertake this on their behalf.

Summary

The analysis indicates that ACCS was seen as being broadly effective and targeted at children who may be vulnerable. At the same time, several issues emerged, particularly the administrative and operational issues summarised above, for ACCS (Child Wellbeing), as well as in regard to challenges for vulnerable families accessing other types of ACCS, particularly ACCS (Temporary Financial Hardship).

Child Care Package evaluation

In July 2018 the Australian Government introduced the Child Care Package. The Australian Institute of Family Studies in association with the Social Research Centre, the UNSW Social Policy Research Centre and the ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods were commissioned by the Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment to undertake an independent evaluation of the new Child Care Package. Findings presented here are based on data collected and analysed for the Child Care Package evaluation. The evaluation commenced in December 2017 prior to the introduction of the Package and reported on data collected up to December 2019. The evaluation was impacted by external events, particularly COVID-19, which resulted in the suspension of the child care funding system for a period during 2020. As a result, the evaluation only draws on data to the end of 2019 and does not include data from 2020.

1 The policy settings described in this snapshot refer to those that applied at the time of the evaluation. There have been some updates to policy settings since this time, and the Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE) is now the Department of Education.

2 Detailed information is available to providers on what may constitute 'serious abuse or neglect'. Two important points are that (1) a child may be considered eligible if they are at risk of experiencing harm due to current or past events relating to serious physical, emotional or psychological abuse, sexual abuse, domestic or family violence or neglect, or if such experiences in the future are considered likely. And (2) children identified as being at risk under state or territory child protection law meet the definition of 'at risk'.

3 Eligibility is grandparents who receive an income support payment, care for their grandchild/ren for 65% or more of the time and have substantial autonomy for day-to-day decisions about the child›s care, welfare and development.

4 Parents or carers (or services, in the case of the ACCS (Child Wellbeing)) may apply for a higher subsidy percentage or a higher number of hours of subsidised care in exceptional circumstances.

5 Use of care refers to how many hours of care were charged for, not how many hours children attended.

6 These analyses are only presented for ACCS (Child Wellbeing) because it is the only type of ACCS that requires applications to be made at the service level.

Australian Institute of Family Studies. (2023). The 2018–2021 Child Care Package Evaluation: Additional Child Care Subsidy. (Findings from the Child Care Package evaluation). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.