Identifying strategies to better support foster, kinship and permanent carers: Summary report

July 2022

Jessica Smart, Stewart Muir, Jody Hughes, Kat Goldsworthy, Sarah Jones, Loma Cuevas-Hewitt, Carol Vale

Download Research snapshot

Overview

During 2020 and 2021 the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) and Murawin did a research project about carers. This research was funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services. The government wanted to know what carers needed so they can attract more carers and keep carers for longer.

To learn about carers, the researchers:

- reviewed published articles about carers and how they can be supported

- spoke with 28 carers and people from 24 organisations and government agencies who work to support carers. Fourteen of the carers we spoke to were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and six of the organisations were Aboriginal community-controlled organisations.

- spoke with both carers and service providers in New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria and Western Australia. We also spoke with service providers in Tasmania.

This snapshot shares what the research team learned about carers, and what they think could help carers better care for kids and stay caring for longer.

Carers in Australia

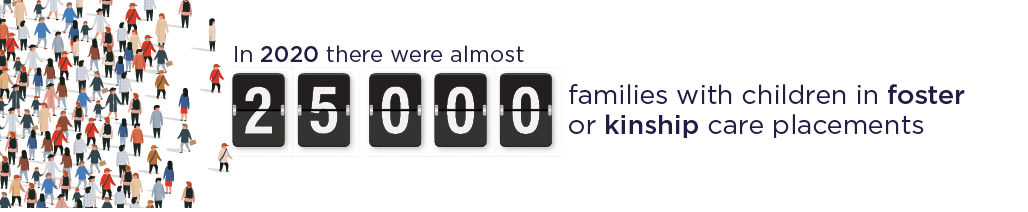

- The number of children in out-of-home care is increasing. Many people from government and out-of-home care services are worried there won’t be enough carers in the future. In particular, there are not enough Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers or carers for children with complex needs.

- There are more children in kinship care than in other types of placements. The number of kinship carers grows each year (by around 1,000), while the number of foster carers decreases (by around 150).

- Overall, most kinship carers are older than foster carers. They are more likely to be single, to have less income and be in poorer health.

Becoming a carer

Nearly all carers said they start caring because they care about children. Different types of carers also start caring for other reasons:

Many carers belong to more than one of these groups; for example, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers are kinship carers. These carers become carers to help their family, keep a child out of care, and keep kids connected with culture and community.

Challenges for carers

- Many of the challenges carers face are to do with the out-of-home care system. These include:

- not getting enough information about the child or the placement

- not being included in decisions about children in their care

- their caseworker constantly changing.

- Carers can experience difficulties meeting children’s needs, face financial challenges associated with being a carer, and find it hard to keep Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kids connected with community, culture and Country.

- Some carers and service providers talked about challenges with keeping kids connected with their birth families, but many of the carers were doing okay with this.

Why carers stop caring

- Most kinship carers will stay as a carer for as long as the child needs – until the child is 18 or is reunited with their birth parents.

- Many foster carers do the same but will then take another foster child. Foster carers usually stop taking placements when something in their life changes and makes it harder to be a carer or when the challenges of caring get too much.

What helps carers

- Carers need different types of support to care for kids.

- Carers need:

- Some carers need:

- help when kids are transitioning in and out of a care placement

- support to have a good relationship with the child’s birth family.

- Some carers were getting the support they needed, but lots of carers did not get enough help. Where a carer lived made a difference to how much support they got. Carers living in regional, rural and remote towns found it hardest to get help.

- Kinship and permanent carers need more support. Kinship carers can become carers very quickly (sometimes overnight) and often don’t get as much preparation or support as foster carers.

- Many carers did not know where to get support from, or had to wait a long time to get help.

- Some services were not culturally safe for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers and some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers might not feel safe using services because of bad experiences in the past.

Carers and COVID-19

- Many of the services that support carers changed to doing things online or over the phone because of COVID-19. This was good for some carers who found it easier to go to meetings and do training online. Other carers who were not used to doing things online or didn’t have the right technology found this hard.

- Carers in different parts of Australia said different things about how they were going with COVID-19. Some carers enjoyed keeping their kids home from school, but others told us that home schooling was hard.

- Some carers had lost work and were worried about money, and some carers were feeling lonely and isolated. Other carers couldn’t access the services they needed, and some kids had a hard time because their routine was disrupted.

- Many carers had a hard time keeping kids connected with their birth families. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in care often have family spread out and in remote areas making it particularly hard for them to keep connected with their culture, community and Country.

What the researchers learned

- Carers make an important and valuable contribution to the community.

- Some children in care have complex needs, and these carers need extra support for the child and for themselves.

- Kinship carers might need more support because they are generally older and less well-off financially, and often don’t get time to prepare to be a carer.

- Quite a bit is known about the challenges of caring, and the types of support that carers need. Not much is known about what types of support help the most. More data and evaluation are needed.

Some ways of working and supports that could help carers

- Including carers in decision making about the child

- Support for kinship carers within three to six months of the placement starting

- Having extended families lead decision making when a child can no longer live with their birth parents, especially for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families

- More understanding of trauma and use of trauma-informed approaches to supporting children and carers

- Caseworkers and carers having a trusting and supportive relationship, and caseworkers having ongoing cultural training

- More peer support networks for carers

- Having Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations make more decisions about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kids in care, and provide more services for carers

- More cultural support for carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children

- More investment in looking for family members who could be carers, especially for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children

- More access to respite care, and respite carers who can build a relationship with a child and a carer over time

- Training for carers that changes over time to match the needs of the child and the carer

- Having more information about what support is available and how carers can access support

The research says that some ways that governments can help carers are:

1. Develop national minimum standards or guidelines that set out what support and training carers should get and when they should get it.

2. Review carer payments across Australia.

© GettyImages/PeopleImages

Smart, J., Muir, S., Hughes, J., Goldsworthy, K., Jones, S., Cuevas-Hewitt, L., & Vale, C. (2022). Identifying strategies to better support foster, kinship and permanent carers: Summary report. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.