Long hours and longings

September 2017

Jennifer Baxter, Lyndall Strazdins, Jianghong Li

Download Research snapshot

Overview

Our study, Long hours and longings, showed that very long hours, non-standard work times and work pressures have a significant impact on how children view time spent with their father. It also showed that a child's view about their father's work demands tends to tally with their father's: that they share the same sentiment.

Key messages

-

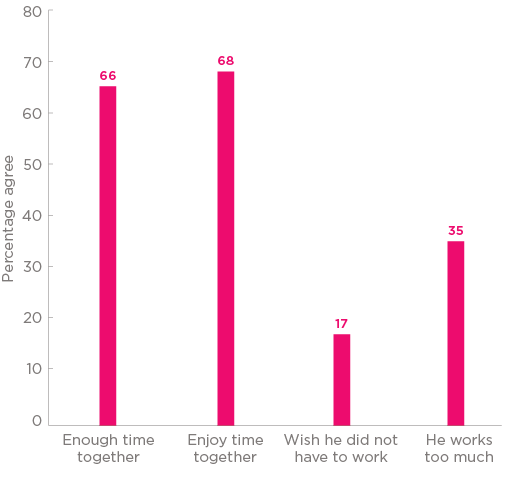

Around a third - 35% - of children considered that their father works too much, and 17% wished that he did not have to work at all. Two-thirds (66%) said they had enough time with dad.

-

Analysis revealed that the things that generated negative views in children about the time demands of their fathers' jobs were: working on weekends; work intensity; being unable to vary start and stop times; and long hours.

-

The frustration felt by fathers in trying to balance work and family demands is shared by their children.

Introduction

Discussions about how to address work-family challenges largely centre on mothers, but the challenges also are real for fathers. There is increased recognition that a "good" father is directly involved in the care of children. But this requires time, and fathers are often time-constrained due to work.

Many fathers in Australia are working long hours and have schedules that are not family-friendly, including evening and weekend work. This can get in the way of their time with children.

Our paper Long hours and longings examines this issue. Central to our study are issues about fathers' work-family balance, and about how children's views and experiences of fathering may be shaped by their father's work.1

Children's voices are rarely heard in debates about work and family, yet they can be discerning observers of how their father's job impacts the family. They appear to be aware of the importance of those jobs for family income, but also of the impact of those jobs on family time.

"I really can't pick, because we need the money, but I also need my parents."

16-year-old from a low-income family. In Pocock, B., & Clarke, J. (2005). Time, money and job spillover: How parents' jobs affect young people. The Journal of Industrial Relations, 47, 62-76.

"He leaves on Monday and comes home on Friday, which is annoying. He spends time with us on the weekends, so he is making up for it."

12-year-old boy. In Brannen, J., Wigfall, V., & Mooney, A. (2012). Sons' perspectives on time with fathers. Diskurs Kindheits- und Jugendforschung Heft, 1, 25-41.

Children's views: Dad's work life

When asked about how much time they had with dad and how they felt about it (see Figure 1), around two in three children said they had enough time, or that they definitely enjoyed time with their dad. Just over one in three said dad works too much, and 17% said they wished he did not have to work.2

Figure 1: Children's views of father's work-family balance

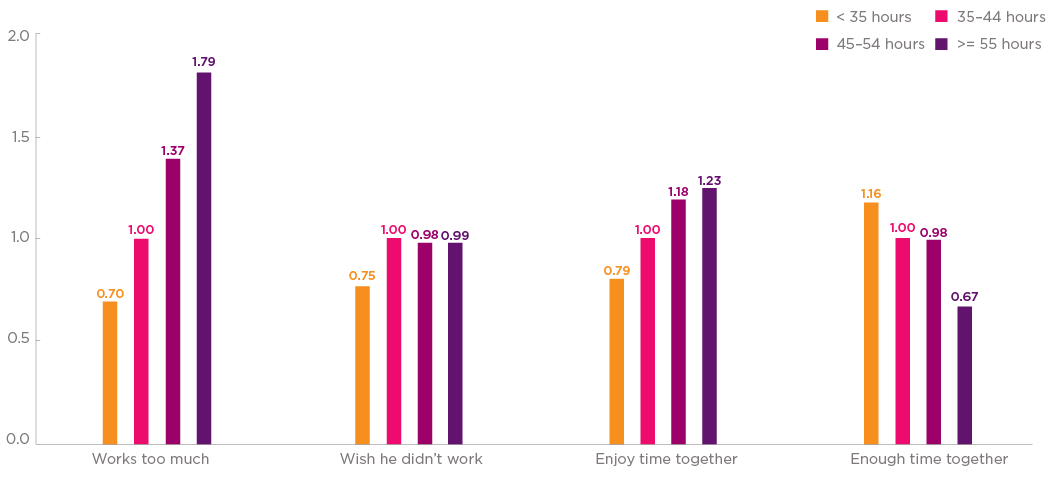

The study analysed the likelihood of a child reporting positively or negatively on their father's work-family situation, and it found that:

- as a father's work hours increased, his children were more likely to say he works too much;

- children were less likely to say they have enough time with dad if their father worked long, full-time hours.

Neither finding is surprising. However, the study also found that:

- children were somewhat more likely to say they enjoy time with dad if their father worked more than standard full-time hours (see Figure 2). This was an unexpected finding that may indicate that when fathers work longer hours, they make greater efforts to focus on fun activities with children during the time they have together.

Figure 2: Children's views of father's work hours

Note: Logistic regression results (odds ratios).3

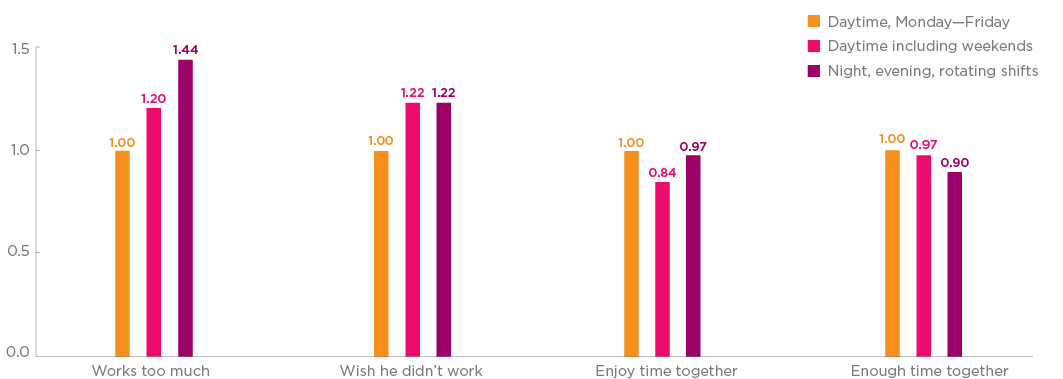

Looking at a father's work schedule - i.e., when dad worked - the study found another set of effects (see Figure 3):

- If dad worked outside of standard day-time hours, children were more likely to say he worked too much. This was especially so if dad worked nights, evenings or rotating shifts. If dad worked some weekends children were also more likely to say he worked too much.

- Children were more likely to say they wish their dad did not have to work if he worked non-standard hours.

- Children were less likely to say they had enough time with dads if he worked non-standard hours, especially if he worked nights, evenings or rotating shifts.

- The children least likely to say they enjoyed time with their dad were those whose dads sometimes worked on weekends.

Figure 3: Children's views of father's work schedule

Note: Logistic regression results (odds ratios).3

If fathers were able to change their work start and stop times, children were less likely to say that they wished he did not have to work. They were also more likely to say they had enough time with dad if he worked flexible hours.

Kids feeling the pressure

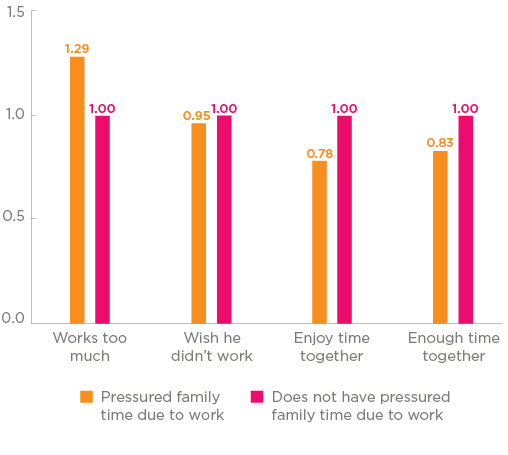

If fathers were classified as having jobs that involved more pressure or intensity, children were more likely to say that he worked too much and less likely to say that they had enough time with him.

Fathers' own reports of how their family time was affected by work were related to how children saw the effects of their fathers' work, even after taking account of the types of job the father did. For example, if a father said that he missed family events due to work, or that he felt his family time was more pressured and less fun due to work, then his children were more likely to say he worked too much. Children were also more likely to say that they wished their father did not have to work if their father said they missed family events due to work. They were less likely to say they enjoyed time together when their father reported that family time was more pressured and less fun due to work.

Figure 4: Children's views on pressured family time

Note: Logistic regression results (odds ratios).

Conclusion

At a time when "fathering" is recognised as more than simply being a breadwinner, there are significant challenges for fathers who wish to be more involved in family activities, but who are prevented by their work. Our findings show that the frustration goes both ways, and that fathers' experiences of work demands are mirrored in their children's experiences of fathering.

1 The study used data collected in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). It looked at children when they were 10-11 years old, and two years later when they were 12-13. The focus was children's answers to series of questions about their fathers' jobs. In total, 5,711 paired father-child observations were used.

2 The key child-reported measures used are: Dad works too much vs about the right amount or too little; Wish dad did not have to work very much vs wish a little bit or don't wish, not a problem; Enjoy time with dad definitely true vs mostly true, mostly not true or definitely not true; Enough time with dad about right or too much, vs nowhere near enough or not quite enough. Multivariate analyses were used to analyse these data, incorporating more detailed information about children and families than has been presented in this research summary.

3 Findings are presented as odds ratios which compare the likelihood of a particular outcome (e.g., children saying their father works too much) across categories of a variable, with one category (35-44 hours) being the reference category. This is shown with an odds ratio equal to one. For other categories, if the odds ratio is greater than one the likelihood of that outcome is greater than for the reference category, and if it is less than one it is less than the reference category. Explanatory variables included in the models were the job characteristics described here as well as some other child and family characteristics.

Media releases

© istockphoto/Wavebreakmedia

This article presents some key findings from Strazdins, L., Baxter, J. A. and Li, J. (2017). Long Hours and Longings: Australian Children's Views of Fathers' Work and Family Time. Journal of Marriage and Family. DOI: 10.1111/jomf.12400