National Elder Abuse Prevalence Study: Summary report

December 2021

Lixia Qu, Rae Kaspiew, Rachel Carson, John De Maio, Jacqui Harvey, Briony Horsfall

Download Research snapshot

Overview

Elder abuse is a serious problem in Australia. It is an issue that needs policy attention, especially because of our ageing population. ABS population projections indicate that over the next 25 years the number of older people (aged over 65 years) will double to around 9 million Australians.

As part of the National Plan to Respond to the Abuse of Older Australians (National Plan, Council of Attorneys General, 2019), the Attorney-General's Department commissioned the National Elder Abuse Prevalence Study (NEAPS) to investigate elder abuse. This is the first national survey and the most extensive study into elder abuse in Australia.

This report summarises the findings of the Survey of Older People (SOP), a nationally representative survey of 7,000 people aged 65 and over living in community dwellings. The fieldwork was conducted from 12 February to 1 May 2020. The survey investigated the prevalence and nature of elder abuse, who is most likely to experience abuse, who commits abuse, and how people respond to abuse. There are some groups this study does not cover, such as people in residential care settings and people with cognitive impairment. Further research is needed on elder abuse among these groups.

Key messages

-

One in six older Australians (15%) reported experiencing abuse in the 12 months prior to being surveyed between February and May 2020.

-

Elder abuse can take the form of psychological abuse (12%), neglect (3%), financial abuse (2%), physical abuse (2%) and sexual abuse (1%).

-

Perpetrators of elder abuse are often family members, mostly adult children, but they can also be friends, neighbours and acquaintances.

-

People with poor physical or psychological health and higher levels of social isolation are more likely to experience elder abuse.

-

Two thirds of older people don't seek help when they are abused (61%).

How many people experience elder abuse and neglect?

One in six older Australians (15%) experienced abuse in the year prior to the survey.

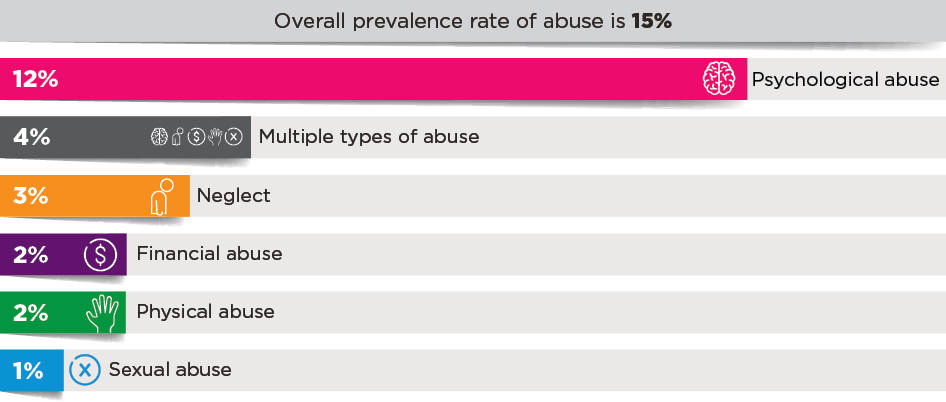

This research shows that 15% of the population aged 65 and over who live in the community (rather than in residential care settings) have experienced elder abuse in the 12 months prior to interview (Figure 1).

Psychological abuse is the most common subtype (12%), followed by neglect (3%), financial abuse (2%), physical abuse (2%) and sexual abuse (1%).

Some people experience more than one subtype of abuse (4%). The most common combination of abuse is psychological abuse and neglect.

Figure 1: Prevalence of elder abuse overall, the five subtypes and multiple types of abuse

Who experiences elder abuse and neglect?

Rates of elder abuse are similar for men and women.

Overall, differences in prevalence of elder abuse between men and women are limited but slightly higher for women than for men (16% cf. 14%). Women are slightly more likely to experience sexual abuse (1.2% cf. 0.7%), psychological abuse (13% cf. 11%) and neglect (4% cf. 2%).

The age group most at risk of abuse are those in the 65-69 years bracket, although the likelihood of neglect rises for those aged 80 and above. It should be noted that some people who may be vulnerable to abuse in other age brackets - such as those with dementia - may be living in residential care. Their experience was not captured in this study.

Low socio-economic status puts older people at higher risk of abuse.

Anyone can experience elder abuse. But there are some characteristics that mean some people are at higher risk of abuse. These include being of lower socio-economic status, being single, separated or divorced and living in rented housing or owning a house with a debt against it.

Poor health and higher social isolation increase risk of elder abuse.

People with poor physical or psychological health and higher levels of social isolation are also at higher risk of abuse.

People who experience elder abuse are more than three times more likely to have psychological wellbeing scores indicative of probable serious mental illness compared with those who don't experience it.

Having poor health or a disability or a medical condition lasting at least six months and causing difficulty in everyday life doubles the risk of experiencing elder abuse.

Those who experience elder abuse have a much lower sense of social support compared to those who don't experience elder abuse.

What protects older people from abuse?

People who are married or living in a relationship and people who own their own home without debt have lower chances of experiencing abuse. However, it should be noted that some perpetrators of elder abuse are intimate partners (see further below).

People with good physical and psychological health and higher levels of social support are also less likely to experience abuse (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Factors associated with lower chances of experiencing elder abuse

Who commits elder abuse and neglect?

Elder abuse perpetrators are mostly family members, especially adult sons and daughters.

Nearly one in five elder abuse perpetrators are children (18%). Partners of children account for 7% and grandchildren 4%. About one in 10 elder abuse perpetrators are intimate partners.

Elder abuse is also perpetrated by people who are socially connected to the victim. Together, friends (12%), neighbours (7%) and acquaintances (e.g. co-workers) (9%) reflect about a quarter of all perpetrators.

Men are more likely to commit elder abuse than women (55% cf. 45%).

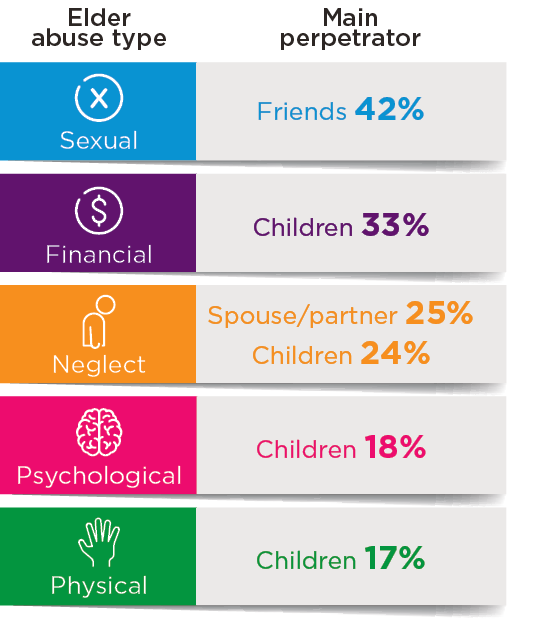

Children are the biggest perpetrator group for all subtypes of elder abuse except sexual abuse. Perpetrator groups differ for each abuse subtype (Figure 3).

For financial abuse, children are the largest perpetrator group (33%). Sons are almost two times more likely than daughters to perpetrate abuse (24% cf. 12%). The two next biggest perpetrator groups for financial abuse are friends (9%) and service providers (6%).

Adult children were the main perpetrator group for psychological abuse (18%). The next largest perpetrator group was acquaintances (12%) followed by sons and daughters in law (10%) friends (10%) and intimate partners (8%).

For physical abuse, children are still the biggest perpetrator group (17%), followed by spouses (12%), neighbours (12%) and friends (10%).

Perpetrator profiles differ significantly for sexual abuse, with friends (42%) followed by acquaintances (13%) and spouses (9%) most likely to commit this type of abuse.

For neglect, children and intimate partners are both significant perpetrator groups (24-25% for each). Professional carers (14%) and service providers (13%) are bigger perpetrator groups for neglect than for other abuse subtypes.

Figure 3: Perpetrator groups for elder abuse overall and the five subtypes

Many of the people who reported experiencing abuse in the survey, also indicated they were aware the perpetrator had problems themselves. The most commonly reported problems were mental health issues (32%), financial problems (21%) and physical health problems (20%).

Do people who experience elder abuse and neglect seek help?

Just over one third of people who experience elder abuse seek help or advice.

The survey asked people who experienced elder abuse whether they sought help or advice or took action to stop the abuse. Most people did not seek help or advice, with only 36% turning to informal or formal sources of support.

However, eight in 10 do take some action to stop the abuse, most commonly speaking directly with the perpetrator (one half). Another common action is breaking contact with or avoiding the perpetrator (four in ten). This is concerning, since it may make the effect of the abuse worse by increasing the older person's isolation. It might also mean that other effective ways of addressing the abuse are not available. Additionally, it means there are no consequences for the perpetrator.

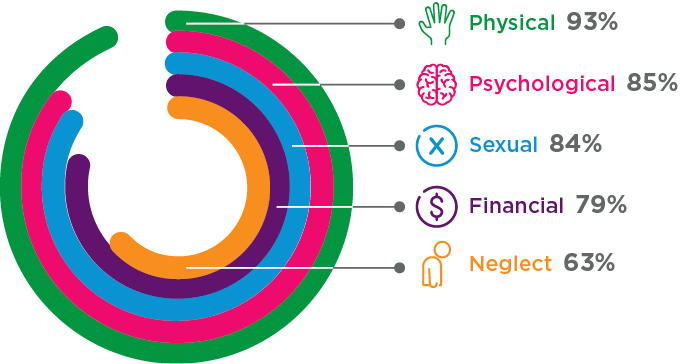

Taking action to stop abuse and seeking help in relation to abuse varies between subtypes. Figure 4 shows the proportion of people who took some action to stop the abuse, by abuse subtype. Actions are most common in relation to physical abuse (93%) and least likely in relation to neglect (63%). Proportions taking action to stop psychological, sexual and financial abuse are similar (79-85%).

Figure 4: Proportion of people who took some action to stop the abuse by subtype

For financial abuse, only 30% said they did seek help or advice from someone else but nearly eight in 10 did something to stop the abuse. Nearly six in 10 said they spoke directly to the perpetrator. Where other action was taken to stop the abuse, breaking contact with the person was most common (30%). Taking legal action was more likely to be reported for this abuse subtype (14%) than any other.

For physical abuse, half of those who experienced it sought help or advice and over nine in 10 did something to stop the abuse. The most common actions to stop physical abuse were breaking contact with the person (64%) and speaking directly to the person (61%).

Sexual abuse was the subtype people were least likely to seek help and advice for, with only one quarter reporting doing so. However, 84% did take action to stop the abuse. Speaking directly to the perpetrator (58%) and breaking contact with them (48%) were common actions. Seeking protection through advice from a lawyer or a personal protection order were both very uncommon (each 1%).

In relation to psychological abuse, four in 10 sought help or advice and 85% took action to stop the abuse from happening. Breaking contact (49%) was almost as common as speaking directly to the person as an action to stop the abuse (52%).

Neglect was the abuse subtype for which help and advice were least likely to be sought (20%). Actions to stop the abuse were also least likely to be taken to stop neglect, with two thirds reporting some action being taken, most commonly speaking directly to the person responsible (48%).

Who do people turn to for help?

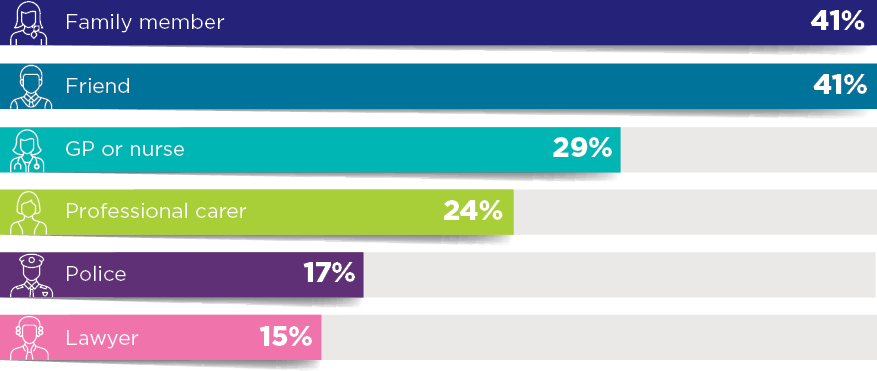

Family and friends, general practitioners and nurses are common sources of support for people who experience elder abuse.

Where older people sought help and advice, it most often involved family members and friends (Figure 5). Otherwise, health professionals, including GPs and nurses, are the most common sources of assistance. Legal responses are more commonly accessed for some abuse subtypes (physical and financial abuse) than others but are not a main source of support.

Figure 5: Most common sources of help and support for elder abuse overall

Help-seeking patterns are different for the abuse types.

For all abuse subtypes, friends and family are almost always the main sources of help for older people. Other than family and friends, patterns in sources of help differ for each subtype. The most common sources of help for each subtype are:

For financial abuse, a professional carer or social worker (34%), GP or nurse (28%), or a lawyer (33%). Police were involved in a quarter of the cases where help or advice were sought.

The physical abuse subgroup was the most likely of all the abuse subtypes to seek help or advice from police (36%), and this was more common than from family members. Otherwise, a professional carer or social worker (26%) and a GP or nurse (22%) were common sources of support.

For sexual abuse, a GP or nurse (35%) and a neighbour (18%) were relied on for help and advice.

For psychological abuse, the most common sources of formal help were a GP or nurse (30%) and a professional carer or social worker (22%).

For neglect, the most common formal sources were a GP or nurse (37%) and a professional carer or social worker (33%).

Implications

This research shows that more needs to be done to prevent, identify and respond to elder abuse. A need for policy and program development in the following areas has been identified:

The development of an evidence-based framework for preventing elder abuse.

This involves developing strategies to reduce vulnerability to abuse by targeting factors such as social isolation and addressing factors that support perpetration of abuse, including secrecy.

Measures to raise awareness of elder abuse and the services that are available to address it.

With family and friends the main sources of support for people who experience elder abuse, it is important that the community is aware of the need to look out for elder abuse. People who experience elder abuse themselves need to know how to access services to address it. People who become aware of someone else's experience of elder abuse also need to be able to provide appropriate support and know that there are services available for people who experience elder abuse.

Improved screening for and assessment of elder abuse in a range of settings, especially health settings.

Given that elder abuse often remains hidden, measures to proactively identify situations where it may be occurring are important. Health professionals such as doctors and nurses are one group that is well-placed to perform this function because they regularly engage with older people and, outside of family and friends, are the group who most often receive disclosures of abuse.

An assessment of the existing ways of responding to the different subtypes of elder abuse.

The low levels of reliance on formal sources of support, and the high levels of avoidant actions, indicate a need to assess whether existing services are accessible, appropriate and adequate.

References

Council of Attorneys-General (CAG). (2019). National Plan to Respond to the Abuse of Older Australian (Elder Abuse) 2019-2023. Canberra: Attorney-General's Department.

Featured image: © GettyImages/katleho Seisa

Qu, L., Kaspiew, R., Carson, R., Roopani, D., De Maio, J., Harvey, J., Horsfall, B. (2021). National Elder Abuse Prevalence Study: Summary Report. (Research Report). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Download Research snapshot

Related publications

National Elder Abuse Prevalence Study: Final Report

This report presents findings from the most extensive study on elder abuse in Australia to date.

Read more

National Elder Abuse Prevalence Study: Data access and usage

Data access and usage terms and procedures

Read more

Elder abuse in Australia: Prevalence

This snapshot provides key findings from the Survey of Older People (2020), a nationally representative survey of 7,000…

Read more