Past and present adoptions in Australia

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

February 2012

Daryl Higgins

Download Research snapshot

Overview

"Adoption" is a word that elicits mixed responses from people. Adoption practices in Australia have varied over time. Given the prevalence of adoption in the past, particularly in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a significant proportion of the population has had some experience of or exposure to issues relating to adoption. This Facts Sheet provides a summary of the ways in which adoption currently operates, past adoption practices, and the potential impacts adoption has on those involved.

Current adoption practices in Australia

There are three types of adoption currently operating in Australia:

- Intercountry adoptions are of children from other countries who are usually unknown to the adoptive parent(s). Since 1999-2000, most adoptions in Australia have been intercountry adoptions. In 2010-11, there were 215, representing 56% of all adoptions.

- Local adoptions are those of children born or permanently residing in Australia, but who generally have had no previous contact or relationship with the adoptive parents. In 2010-11, there were 45 local adoptions, representing 12% of all adoptions.

- "Known" child adoptions are of children born or permanently residing in Australia who have a pre-existing relationship with the adoptive parent(s), such as step-parents, other relatives and carers. In 2010-11, there were 124 "known" child adoptions, representing 32% of all adoptions. (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2012)

Despite the large growth in the number of Australian children in out-of-home care over the last two decades, adoption of these children is rare. This is because there is a strong push for them to be restored to or maintain active contact with their parents. In addition, most jurisdictions have the capacity to: (a) make permanent care orders (which provide security of placement with a foster/kinship carer); and/or (b) have policies relating to the creation of permanency plans 1 when there is no foreseeable likelihood of children being able to safely return to the care of their parents. Unlike adoption, these foster/kinship care arrangements do not formally extend past a child turning 18 years of age.

1 "Permanency planning" refers to making decisions about alternative long-term foster/kinship care placements for children as early as possible to avoid the negative consequences of continuing to have failed attempts to restore children with birth parents.

History of adoption

Concerns about high levels of infant mortality and occasional reports of infanticide cases led to the first legislation on adoption in Australia being enacted in Western Australia in 1896, with similar legislation following in other jurisdictions from the 1920s.

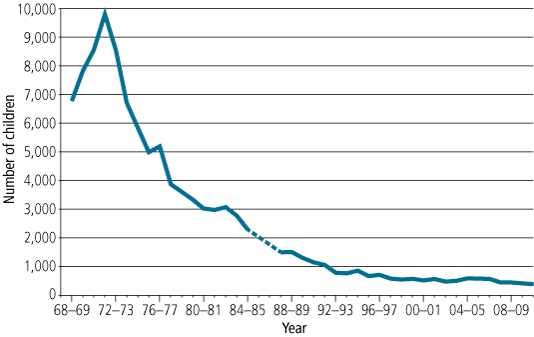

In the decades prior to the mid-1970s, it was common in Australia for babies of unwed mothers to be adopted. At its peak in 1971-72, there were almost 10,000 adoptions (see Figure 1). Since then, rates of adoption have dropped massively, and over the last two decades have remained relatively stable at around 400-600 children per year (e.g., there were 384 adoptions in 2010-11; AIHW, 2012).

Figure 1: Number of adoptions in Australia from 1968-69 to 2010-11

Note: National data were not collected between 1985-86 and 1986-87.

Source: AIHW (2009; 2012)

This significant change in adoption rates coincided with a range of legislative, social and economic factors, such as:

- greater social acceptance of raising children outside registered marriage, accompanied by an increasing proportion of children being born outside marriage;2

- increased levels of support available to lone parents (e.g., the Supporting Mothers Benefit was introduced in 1973);

- increased availability and effectiveness of birth control;3 and

- declining birth rates.

Closed adoption

From the 1920s, adoption practice in Australia reflected the concept of secrecy and the ideal of having a "clean break" from the birth parents. Closed adoption is where an adopted child's original birth certificate is sealed forever and an amended birth certificate issued that establishes the child's new identity and relationship with their adoptive family. Legislative changes in the 1960s tightened these secrecy provisions, ensuring that neither party saw each others' names.

The experience of closed adoption included people being subjected to unauthorised separation from their child, which then resulted in what was often called "forced adoption". From the 1940s, adoption advocates saw it as desirable to relinquish the child as soon as possible, preferably straight after birth.4

From the 1970s, advocacy led to legislative reforms that overturned the blanket of secrecy surrounding adoption, though until further changes were made in the 1980s (or 1990s in some Australian jurisdictions), information on birth parents was not made available to adopted children/adults.

Beginning with NSW in 1976, registers were established for both birth parents and adopted children who wished to make contact. In 1984, Victoria implemented legislation granting adopted persons over the age of 18 the right to access their birth certificate (subject to mandatory counselling). Similar changes followed in other states (e.g., NSW introduced the Adoption Information Act in 1990).

Reunion services are now part of the ways in which governments and agencies are trying to address the negative impacts of separation on (birth) parents and children from these past adoption practices.

Open adoption

The practice of closed adoption changed gradually across each of the states and territories in Australia from the late 1970s through the 80s and 90s.

With the implementation of these legislative changes, adoption practices shifted away from secrecy. Now, the vast majority (84% in 2010-11) of local adoptions (but not intercountry adoptions) are "open", where the identities of birth parent(s) are able to be known to adoptees and adoptive families. Among local adoptions, only 16% of birth parents in 2010-11 requested no contact or exchange of information with the adoptive family (AIHW, 2012).

Open adoption has led to a number of improvements in practices, such as:

- more accountable processes for obtaining consent from (birth) parents;

- a requirement for consent to be provided by both birth parents (or the need for a parent's consent to be dispensed with by a court for a child's adoption to proceed); and

- higher quality assessments and benchmarks for assessing the suitability of prospective adopters.

2 The Council of the Single Mother and Her Children, set up in 1969, aimed to challenge the stigma of adoption and provide support to single and "relinquishing" mothers. The status of "illegitimacy" disappeared in the early 1970s, starting in 1974 with a Status of Children Act in both Victoria and Tasmania (in which the status of such births was changed to "ex-nuptial").

3 Abortion also became allowable under some circumstances in most states from the early 1970s; see the 1969 Menhennitt ruling (R v Davidson) in Victoria and the 1971 Levine ruling in NSW.

4 Women's magazines became fierce advocates for adoption, with waiting lists of prospective adoptive parents beginning to emerge in the 1940s and 1950s. As demand for babies outstripped supply (though not for babies with disabilities), the pressure to relinquish was particularly high in maternity homes, where matrons and social workers were often personally acquainted with the prospective adoptive parents (see Marshall & McDonald, 2001; Swain & Howe, 1995).

Impact of past adoption experiences

There is limited research available in Australia on the issue of adoption practices during and following the period of closed adoption in Australia. The available information highlights a number of important issues:

- There was a range of people involved, and therefore the impacts and "ripple effects" of adoption reach beyond mothers and the children who were adopted, to include fathers, spouses and other family members.

- One issue of particular importance is the trauma of the separation of mother and child, and the resulting experience of grief and loss. Mothers - particularly those who have not had any contact - continue to be traumatised by the thought that their child grew up thinking that they were not wanted:

- An adoptee, after meeting her mother late in life, said of her: "There has hardly been a day in her life that she hasn't wondered where I was or had (I) ever survived" (cited in Swain & Swain, 1992, p. 47).

- In the words of one mother: "It wasn't the children who were not wanted. Mothers weren't wanted because they were unmarried" (cited in Higgins, 2010, p. 13).

- There is anecdotal evidence of variability in adoption practices, ranging from women feeling that they were supported in making an informed decision, to reports of unjust, cruel and unlawful behaviours towards young unmarried pregnant women who were giving birth.

- Past adoption practices continue to affect the daily lives of many people, including the process of reunion between birth parents and adoptees (their now adult children), and the degree to which reunion is seen as a "success" or not.

From these identified issues, it is evident that there is a need for better information, counselling and support for those affected by past adoption practices. Additionally, more research is needed about the current views of adoptive families and their experiences of closed adoption, as well as the experiences of adoptees (including their perspectives on reunion and their experiences of reunion services).

Understanding the impact of closed adoption

Participants are being sought for a nationwide study into past adoption experiences to identify the support and service needs of people affected by closed adoption.5

Two surveys are being conducted. These are for:

- people affected by past adoption practices, and

- service providers.

For the first survey, input is being sought from people who were affected in any way, such as:

- individuals who have been separated from a child by adoption;

- people who were adopted;

- adoptive parents; and

- any other family members who were affected by an adoption (including other children, spouses and grandparents).

The second survey is for professionals servicing the current needs of people affected by adoption (e.g., counsellors and psychologists).

The researchers are particularly keen to hear from these professionals, and an online survey and personal interviews are being conducted. Please see the website for further information.

The researchers are seeking to compile a complete picture of people’s adoption experiences, during and following the times of closed adoption, in order to better understand their current needs for support and services.

After the data have been analysed, a report will be made to government in June 2012.

5 This study has been commissioned by the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, on behalf of the Community and Disability Services Ministers Council.

References and further reading

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2009). Adoptions Australia 2007-08 (Child Welfare Series No. 46; Cat. No. CWS 34). Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from <www.aihw.gov.au/publications/>.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2012). Adoptions Australia 2010-11 (Child Welfare Series No. 52). Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from <www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=10737420776>.

- Higgins, D. J. (2010). Impact of past adoption practices: Summary of key issues from Australian research (PDF 200KB). Australian Journal of Adoption, 2(2). Retrieved from <www.nla.gov.au/openpublish/index.php/aja/article/view/1712/2074>.

- Higgins, D. J. (2011a). Current trauma: The impact of adoption practices up to the early 1970s. Family Relationships Quarterly, 19, 6-9. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/afrc/pubs/newsletter/frq019/frq019-2.html>.

- Higgins, D. J. (2011b). Protecting children: Evolving systems. Family Matters, 89, 5-10.

- Higgins, D. J. (2011c). Unfit mothers … unjust practices? Key issues from Australian research on the impact of past adoption practices. Family Matters, 87, 56-67. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/institute/pubs/fm2011/fm87/fm87g.html>

- Marshall, A., & McDonald, M. (2001). The many-sided triangle: Adoption in Australia. Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press.

- Swain, P., & Swain, S. (Eds.) (1992). The search of self: The experience of access to adoption information. Sydney: Federation Press.

- Swain, S., & Howe, R. (1995). Single mothers and their children: Disposal, punishment and survival in Australia. Oakleigh, Vic.: Cambridge University Press.

Media releases

At the time of writing, Dr Daryl Higgins was the Deputy Director (Research) at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Higgins, D. (2012). Past and present adoptions in Australia. (Facts Sheet). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.