Stay-at-home dads

Download Research snapshot

Overview

It's generally perceived that "stay-at-home dads" are becoming more common, as modern families strive to juggle their work and care responsibilities. This Families Week fact sheet takes a close look at the data, to see if that perception matches reality. We have confined our analysis to two-parent, opposite-sex families; this allows us to compare and contrast stay-at-home-father families with stay-at-home-mother families. And because we are focussing on that comparison, other family forms, such as single-parent and same-sex-parented families, are not covered in this fact sheet.

Key messages

-

Stay-at-home fathering is not a common approach in Australia.

-

Stay-at-home-father families are very diverse. They include fathers who are looking for work and those who are not, and mothers who are working part-time and mothers who are working full-time.

-

Stay-at-home-father families tend not have a lot in common with stay-at-home-mother families. Children tend to be older, and mothers still take on much of the caring and household work, even if fathers have increased responsibility for child care.

-

While stay-at-home-father families are (not surprisingly) supportive of fathers caring and mothers earning, there is considerable support for this arrangement across the parenting spectrum.

What is a stay-at-home dad?

We will refer to a father as "stay at home" if he has children aged under 15 years living with him, he is not working, and he has a spouse or partner who is working some hours.1

Smaller scale studies on stay-at-home fathering tend to rely on fathers' self-reports of being stay-at-home fathers.2 We, on the other hand, are relying on data from two large-scale studies: the Australian Population Census and the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) study.

We also recognise that some of the fathers counted here may not consider themselves to be stay-at-home dads (e.g., they may identify as being temporarily unemployed). And others who are in limited employment - perhaps for just a few hours a week - may consider themselves to be stay-at-home dads but do not fall under our definition of stay-at-home dad.

1 A similar approach to this has been used elsewhere, although with underlying differences in the data used. See, for example Kramer, K. Z., & Kramer, A. (2016). At-Home Father Families in the United States: Gender Ideology, Human Capital, and Unemployment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(5), 1315-1331.

2 For example, see Doucet, A. (2004). "It's Almost Like I Have a Job, but I Don't Get Paid": Fathers at Home Reconfiguring Work, Care, and Masculinity. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice about Men as Fathers, 2(3), 277-303.

How many stay-at-home dads are there?

Applying the definition described above, in the census week in 2011:

- There were approximately 68,500 families with stay-at-home fathers. This represented 4% of two-parent families.

- In comparison, there were 495,600 families with stay-at-home mothers (if the same definition is applied to mothers), which was 31% of two-parent families.

- In 57% of families, both parents did some paid work; and in the remaining 7%, neither did any paid work.

Drawing on the ABS Labour Force Survey, we estimate that there were 75,000 stay-at-home-father families in June 2016. This represented 4% of two-parent families, suggesting little change over the previous five years.3

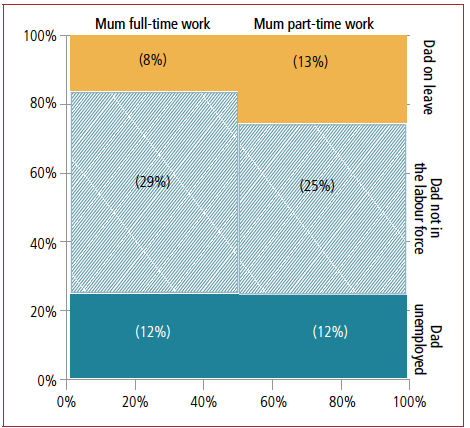

From 1981 to 2011, the estimated number of stay-at-home-father families increased off a low base until plateauing in 2001, as shown in Figure 1.4

Figure 1: Stay-at-home-father families, 1981 to 2011

Source: Australian Population Census 4

3 Derived from Table 9.1, 6224.0.55.001 Labour Force, Australia: Labour Force Status and Other Characteristics of Families, June 2016.

4 The estimates for 1981 and 1986 were derived from the Census one per cent confidentialised unit record files. The estimates for 1991 to 2011 were derived from custom data reports provided by the ABS. All estimates are based on two-parent families with children aged under 15 years, excluding families in which either parent had not stated labour force status.

Parents' employment in stay-at-home-father families

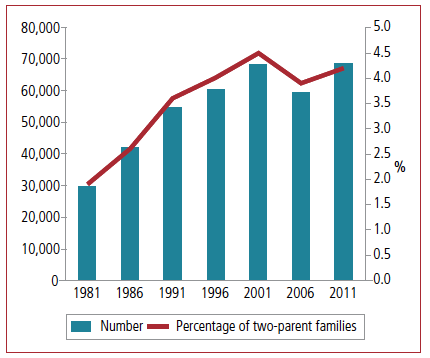

Stay-at-home-father families are very diverse (see Figure 2), with some fathers unemployed (so actively seeking work), some not in the labour force (not looking for work, for a variety of reasons) and some with a job but not working any hours in that job (referred to here as "on leave"). In these families, mothers may work part-time or full-time hours.

Figure 2: Parents' employment in stay-at-home-father families, 2011

Note: Part-time hours is <35 hours per week.

Source: Australian Population Census, 2011 (see Endnote 4).

Age of youngest child in stay-at-home-father families

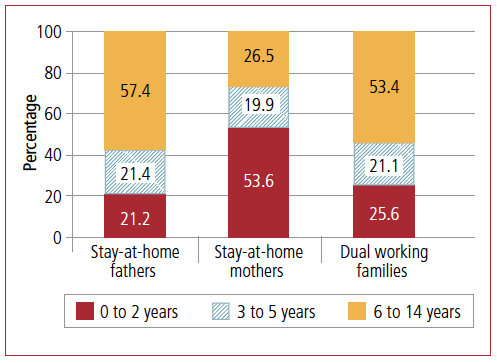

Are stay-at-home-father families like stay-at-home-mother families, just with gender roles reversed? One clue is the age of the youngest child in each of these types of families. In Figure 3, we compare stay-at-home father, stay-at-home mother and dual-working families to see the similarities and differences.

Figure 3: Age of youngest child in stay-at-home-father families, stay-at-home-mother families and dual-working families,

Source: Australian Population Census, 2011 (see Footnote no.4).

The comparison shows:

- Stay-at-home-mother families are considerably more likely to have younger children compared to stay-at-home-father families.

- The age distribution of the youngest child in stay-at-home-father families is similar to that of dual-working families.

Time use in stay-at-home-father families

With respect to housework, child care and employment, do stay-at-home-father families and stay-at-home-mother families divide their time in similar ways?

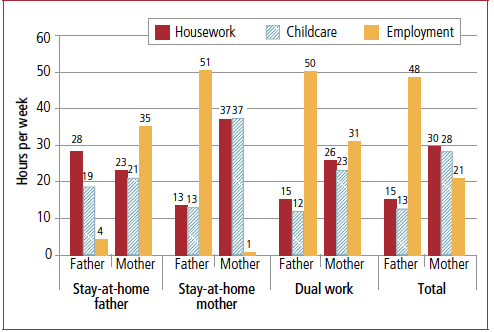

Time-use data is available from the HILDA study,5 in which respondents report on how much time per week they typically spend in a number of activities, including "Housework", "Child care" and "Employment".6 Over the years 2002 to 2015, for families in which at least one parent was employed:

- Fathers averaged 48 hours per week on employment, 15 hours per week on housework and 13 hours per week on childcare.

- Mothers averaged 21 hours per week on employment, 30 hours per week on housework and 28 hours per week on childcare.

This time-use data by family employment arrangement is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Time use of parents by family employment arrangement

Source: Pooled HILDA data, Wave 2 to 15

In stay-at-home-mother families:

- mothers spent 37 hours on each of child care and housework;

- fathers spent 13 hours per week on child care and housework; and

- fathers averaged 51 hours per week on paid work.

In stay-at-home-father families:

- mothers and fathers spent similar amounts of time on childcare (21 and 19 hours, respectively);

- fathers spent a little more time than mothers on housework (28 compared to 23 hours); and

- mothers averaged 35 hours per week on paid work.

This is not the reverse of stay-at-home-mother families.

As stay-at-home-mother families tend to have younger children than stay-at-home-father families, this will account for some of the differences in child-care time. Younger children require more care.

5 The HILDA project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services, and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). All HILDA analysis is based on responses of mothers and fathers with children aged under 15 years.

6 "Housework" includes housework, household errands and outdoor tasks such as home maintenance, car maintenance and gardening; "Child care" includes playing with own children, helping them with personal care, teaching or supervising them, or driving them places; "Employment" includes paid employment and commuting.

Specific child-care activities by family type

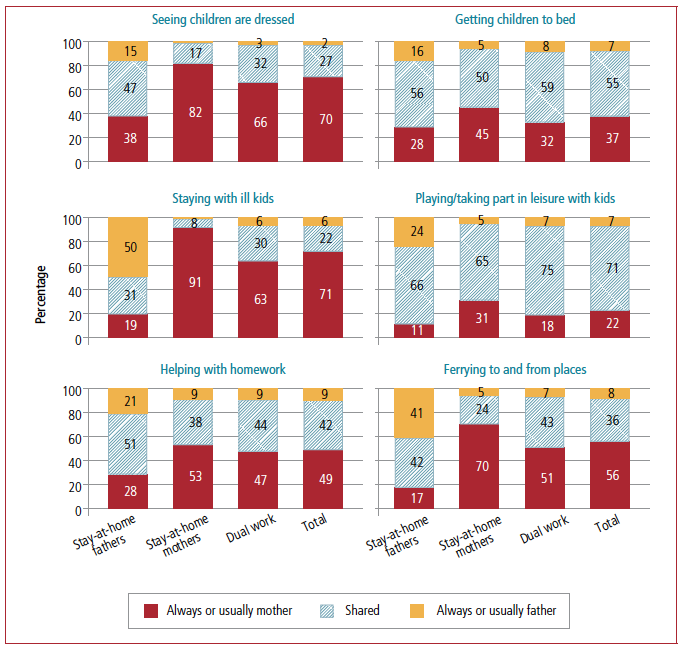

The HILDA study collected extensive detail about the sharing of particular child-care activities - see Figure 5.7

Figure 5: Sharing of specific child-care arrangements, by family employment arrangement

Source: Pooled data from HILDA Waves 1, 5, 8 11, 15

Each of the specific activities in Figure 5 are most often done always or usually by the mother, or shared between mothers and fathers. It is uncommon for child care activities to be done always or usually by the father.

- Activities that are most often shared are playing with children and taking them to leisure activities, and getting children to bed.

When comparing child-care activities by parents in different types of families we see that:

- In stay-at-home-father families, it is more likely that activities are done always or usually by the father. This is especially so for staying home with sick children and for ferrying children to and from places.

The data show that stay-at-home fathers do take on more responsibility for child care than fathers in other family forms, but that the average stay-at-home dad is still far from "Mr. Mum".

7 These questions are not asked every wave. The specific activities were "Dressing the children or seeing that the children are properly dressed", "Putting the children to bed and/or seeing that they go to bed", "Staying at home with the children when they are ill", "Playing with the children and/or taking part in leisure activities with them", "Helping the children with homework", "Ferrying the children to and from places (such as school, child care or leisure activities)."

Parents' attitudes towards stay-at-home-father families

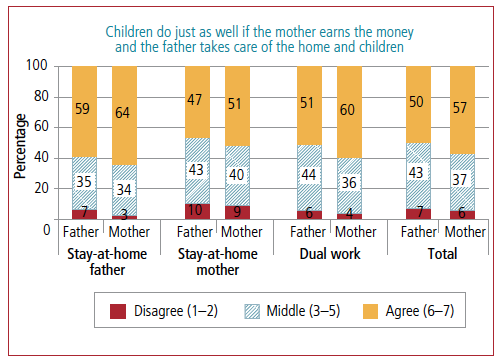

Parents' attitudes toward parenting roles may influence the roles they adopt, or their attitudes may be shaped by the roles they're expected to perform. To explore how attitudes and employment arrangements are related, we focus here on parents' responses to this statement:

Children do just as well if the mother earns the money and the father takes care of the home and children. Parents were asked to indicate whether they agree with this statement, on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), which we have grouped into "disagree" (a score of 1 or 2), "middle" (3 o 5) or "agree" (6 or 7).

Responses (see Figure 6) indicated:

- Around half (57% of mothers and 50% of fathers) agreed that children will do just as well. Very few disagreed (6-7% of mothers and fathers).

- Parents in stay-at-home-father families were most likely to agree that children do just as well. Parents in stay-at-home-mother families were least likely to agree.

However, across the board, most parents agreed that children do just as well in stay-at-home-father families.

Figure 6: Parenting attitudes of mothers and fathers by family employment arrangements

Source: Pooled data from HILDA Waves 1, 5, 8 11, 15

Media releases

Dr Jennifer Baxter is a Senior Research Fellow at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Feature image: © iStockphoto/Halfpoint

Baxter, J. (2017). Stay-at-home dads (Facts Sheet). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

978-1-76016-124-8