Collective impact: Evidence and implications for practice

October 2017

Download Practice guide

Overview

Collective impact has resonated with practitioners and been rapidly adopted in Australia and overseas. This paper explores the collective impact framework and its ability to create population-level change on complex social issues. It describes the history and development of collective impact, with a focus on Australia, and includes two case studies to examine how collective impact is currently being practised in Australia.

Key messages

-

The complex or "wicked" social problems in Australian communities cannot be solved through traditional models of service-based program delivery.

-

Collective impact is a collaborative approach to addressing complex social issues, consisting of five conditions: a common agenda; continuous communication; mutually reinforcing activities; backbone support; and shared measurement.

-

Collective impact is in the early stages of development as a framework for change. As a result there has been limited evaluation and there is not yet a rigorous evidence base to support its effectiveness.

-

Collective impact has been criticised for its failure to adequately address equity, include the voices of community members and to seek policy and systemic change.

-

Collective impact projects are likely to be more effective if they research the issue and context, include community members in decision-making, and examine the evidence for effective strategies.

Introduction

There is a long history of collaborative community-based projects in Australia and internationally; however, the term "collective impact" is relatively new. It was first applied to collaborative projects in 2011 in an article that described the five conditions necessary to achieve collective impact on complex social issues.

While there has been a proliferation of collective impact projects in the years since 2011, the development of an evidence base to demonstrate effectiveness and support development of collective impact is still in its infancy. While collective impact has resonated with practitioners, it has also attracted criticism, particularly for its failure to address issues of structural inequity, engage with community members, and seek policy and systemic change. This paper seeks to explore what we know about collective impact and how it can be most effectively implemented to create change on complex social issues.

Addressing complex issues through place-based approaches

Complex issues are the result of multiple and intersecting causes, and although the evidence base is still emerging, it is suggested that complex and multi-faceted interventions are required. This is often conceptualised in the form of a "place-based approach". A place-based approach is implemented at the local level and focuses on addressing the collective issues of community members through interventions aimed at the social and physical environment rather than individuals or families (Moore & Fry, 2011).

The Centre for Community Child Health (Fry, Keyes, Laidlaw, & West, 2014) have described key steps to be taken to achieve improved outcomes for children. They suggest that outcomes for children will be improved if providers of place-based initiatives work collaboratively with stakeholders and local communities to identify goals and to undertake actions that improve the conditions under which families and communities live, work and raise children.

This needs to be done while providing direct support to families that need it and working in a collaborative and flexible way with families. To do this requires simultaneous action on three fronts: "building more supportive communities, creating a better coordinated and more effective service system, and improving the interface between communities and services" (Moore & Fry, 2011, p. v). There is a significant number of place-based initiatives in Australia that vary considerably in definition of "place-based" as well as the scale, goals and focus of the initiative, its membership and structure, the activities undertaken and how these activities are implemented (Fry et al., 2014).

What is collective impact?

One approach that is frequently employed in a place-based setting is collective impact. Although collective impact could be employed in another way, the majority of collective impact projects are place-based. Collective impact is based on the premise that existing approaches to creating social impact are ineffective for solving complex social issues and a different approach is needed when addressing complexity. The current approach where single organisations address specific issues is termed "isolated impact" (Kania & Kramer, 2011). This is contrasted with collective impact, where stakeholders collaborate across sectors to address complex social issues in local communities (Christens & Inzeo, 2015; Kania & Kramer, 2011).

The term "collective impact" was coined by Kania and Kramer (2011) of FSG Consulting, in 2011, in an article in the Stanford Social Innovation Review. The collective impact framework consists of five conditions drawn from case studies of collaborative projects that have achieved population-level change.

The original theory of collective impact is laid out in three "foundational articles" (LeChasseur, 2016) published by FSG Consulting in the Stanford Social Innovation Review between 2011 and 2013 (Hanleybrown, Kania, & Kramer, 2012; Kania & Kramer, 2011, 2013). Collective impact theorises that meeting the five conditions will lead to population-level change on complex social issues through the emergence and implementation of previously unidentified or unachievable solutions (Kania & Kramer, 2013). The five conditions are described in Figure 1 and Box 1.

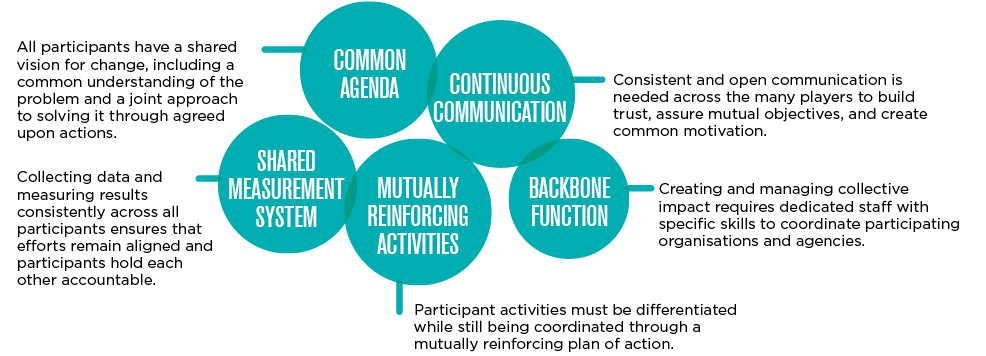

Figure 1: Five conditions of collective impact

Source: Preskill, Parkhurst, & Splansky Juster, 2014

Collective impact has been rapidly adopted in the years since its inception, particularly in the United States, Canada and Australia. The original five conditions are now supplemented by a rapidly growing body of literature that includes additional or updated sets of conditions, pre-conditions, principles and phases, and most of which is published online rather than in academic journals. Collective impact is grounded in practice, and although initially described as an entirely new way of working (Kania & Kramer, 2011), collective impact is more accurately described as a "distillation" of existing knowledge and practice wisdom into a concise set of conditions that can guide collaborative work (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016). The inclusion of a shared measurement system and the focus on dedicated resources via the backbone organisation are unique elements of collective impact that differentiate it from other models of network-based collaboration (Salignac, Wilcox, Marjolin, & Adams, 2017).

Collective impact is not a solution but rather a problem-solving process that enables solutions to emerge through the application of the collective impact framework (Preskill et al., 2014). The concept of emergence comes from complexity science and systems theory and in collective impact is used to describe events or outcomes that develop from interactions between the many interdependent actors and variables. In complex systems, the outcomes of interventions cannot be predicted or controlled (Kania & Kramer, 2013).

This is different to the application of "technical solutions", which to date has been the predominant method of problem solving in the social services sector (Kania, Hanleybrown, & Splansky Juster, 2014). A technical solution can be implemented by a single individual or organisation and the outcome can be predicted with some certainty, whereas the complex and wicked problems that collective impact seeks to address have no known solutions, require input and knowledge from a range of stakeholders across different sectors, and the outcomes of interventions that seek to address them are unpredictable (Senge, Hamilton, & Kania, 2015).

Box 1: Five conditions of collective impact

1. A common agenda

The stakeholders within a collective impact initiative must hold a shared vision for the initiative that incorporates a joint understanding of the social issue that they are trying to affect and agreement upon actions to be undertaken to create change (Kania & Kramer, 2011).

2. Continuous communication

In order to build trust among collective impact stakeholders, continuous communication is required. It is recommended that this take the form of regular meetings between high-level leaders over several years (Kania & Kramer, 2011).

3. Backbone support organisation

Collaborative work requires a supportive infrastructure in the form of dedicated staff and resources. Backbone support organisations have six essential functions: overseeing strategic direction; facilitating stakeholder communication; monitoring data collection and analysis; managing funding; coordinating community outreach; and communications (Hanleybrown et al., 2012).

4. Mutually reinforcing activities

A collective impact approach requires that stakeholders' actions are coordinated. Stakeholders are likely to be undertaking different actions but these actions should all contribute to the same goal, and should complement each other as outlined by an overarching plan of action (Kania & Kramer, 2011).

5. Shared measurement

The stakeholders involved in the initiative collaboratively develop a set of shared indicators against which progress is measured. It is expected that once data is collected against these indicators, the stakeholders will regularly meet to refine strategies based on their results. The backbone support organisation plays a key role in enabling shared measurement, potentially training, facilitating, collating or reviewing data or data collection methods (Hanleybrown et al., 2012).

Collective impact was developed in the United States and although there are examples of collective impact projects across the world, the majority of projects are in North America and Australia (Salignac et al., 2017). There are important contextual differences between North America and Australia that influence the way collective impact is interpreted and practised; however, due to the emerging nature of the field, the literature, particularly academic literature, is limited and most has originated in North America.

Box 2 presents an overview of collective impact in Australia drawing on the available literature and supplemented by discussion with Kerry Graham, the Managing Director of Collaboration for Impact, lecturer with the Centre for Social Impact and consultant on a range of collective impact projects across Australia. This section was further informed through discussions with Sue West and Tim Moore from the Centre for Community Child Health. Both have considerable experience in place-based approaches.

Two current Australian collective impact projects, Logan Together and the Blue Mountains Stronger Families Alliance, are examined in Box 3 and Box 4.

Box 2: Collective impact in Australia

Collective impact has been enthusiastically adopted in Australia. It is estimated that there are more than 80 collective impact-style projects currently being implemented across the country (Graham & Weaver, 2016). Despite the rapid proliferation of projects, collective impact remains a new and emerging phenomenon that is "still taking shape in Australia" (Salignac et al., 2017, p. 12), particularly when compared with the United States and Canada (Graham & Weaver, 2016; Moore & West, 2016 [personal communication]) where it is more established.

When the original article on collective impact was published in 2011 it resonated in Australia. Collaborative networks and alliances recognised themselves and their work in the description and the five conditions outlined by Kania and Kramer (2011), resulting in a proliferation of Australian collective impact initiatives that either began in response to the framework or applied the framework retrospectively to their work (Salignac et al., 2017). The uptake of collective impact in Australia is both part and extension of the place-based work focused on sites of entrenched disadvantage (Graham & Weaver, 2016) that developed in the 1990s with interventions based on principles of place management, service coordination and community engagement (Cortis, 2008). Graham believes that the collective impact framework has added a lens of complexity to the place-based work that was already being done in Australia (Graham & Weaver, 2016).

The majority of the research and commentary around collective impact is coming from North America; however, there are important differences in the Australian context that influence the application of the collective impact framework. In Australia, there is a smaller philanthropic sector and a greater role for all levels of government than in the United States or Canada, where the government plays a lesser role in service funding and service provision (Salignac et al., 2017). The role of government becomes even more significant in rural and remote areas of Australia where it may be one of the only funders or service providers (Graham, 2017 [personal communication]).

One of the impacts of the larger role of government in service provision in Australia is a more programmatic focus within the social services sector and less flexibility and community responsiveness that means service providers are demonstrating accountability to their contract rather than the needs of the community (Graham, 2017 [personal communication]). Another consequence of the greater role of government as a service provider and funder means a smaller philanthropic sector that is less diverse and innovative than the United States, and less likely to invest in systems change initiatives as opposed to programmatic interventions (Graham, 2017 [personal communication]).

There also appears to be greater flexibility within Australia in the way sites are implementing the collective impact framework when compared with the United States (Graham, 2017 [personal communication]; Moore & West, 2016 [personal communication]), particularly with regard to the level of community engagement and collaboration. The history of community development in Australia, the influence of the shift towards co-design of services and, particularly in Indigenous communities, principles of self-determination, have resulted in a greater number of collective impact projects that demonstrate genuine inclusion of communities and understand the need for grassroots change and leadership (Graham, 2017 [personal communication]).

Implementation of collective impact in Australia is diverse. While some sites are engaged with the collective impact literature, learning from and sharing their experiences with other sites and including community members as equal stakeholders, there are other sites that are only adopting some elements of the framework.

Critiques of collective impact

Collective impact has gained much attention from practitioners, funders and governments and with this attention has come considerable criticism. A review of the literature identified four key areas of criticism: collective impact's failure to address inequity; the need to include a focus on policy and systems to achieve change; the failure to draw upon the evidence from other collaborative change efforts; and the lack of community engagement. There have been varying amounts of commentary, adaptation and supplementary resources created in response to these criticisms. However, it is unclear to what extent practitioners are using and referring to the growing body of critically engaged literature and commentary on collective impact.

Equity in collective impact

To increase the likelihood that a collective impact project will achieve population-level change, equity must be addressed in all elements of a collective impact process: data collection and analysis, the selection and role of the backbone organisation and the design of interventions (McAfee, Glover Blackwell, & Bell, 2015). The five conditions of collective impact do not mention equity and do not address the need to include people with lived experience of the issue being addressed in the collective impact process. This has been one of the strongest and most robust criticisms of the collective impact framework, and one made by many authors and practitioners (Brady, 2015; Himmelman et al., 2017; McAfee et al., 2015; Williams & Marxer, 2014; Wolff, 2016). While this has been acknowledged and equity has been addressed in additional collective impact resources (e.g., Collective Impact Forum, 2016; Kania & Kramer, 2015), its omission from the five conditions remains problematic.

The causes of many social issues that collective impact projects seek to address are rooted in structural inequities, in particular issues of race and class (LeChasseur, 2016; Weaver, 2016; Wolff, 2016). Wolff (2016) observed that coalitions and collaborations in the United States are increasingly undertaking "root cause" analysis of the issues they are seeking to change, bringing to light systemic and structural racism, the social determinants of health and issues of social justice and inequality. However, LeChasseur's (2016) research, analysing the foundational articles of collective impact, found that they advocate a "colour-blind, class-blind approach" (p. 232).

Diverse membership has been identified as a key element of successful coalitions (Christens & Inzeo, 2015), and so it is suggested that the early collective impact publications' focus on service providers, and high-level leaders as the agents and drivers of change was problematic (LeChasseur, 2016). While engaging services and their senior leaders is important, having them as the sole members and leaders of a collective impact initiative is likely to limit the extent of change that can be made, as service providers are more likely to identify service-based solutions that may not address the structural causes at the centre of many of the social issues that collective impact projects seek to address (LeChasseur, 2016).

Likewise, the choice and role of the backbone organisation also has implications for equity. Backbone organisations must be willing to address structural inequity and structural racism and must have credibility in diverse communities (McAfee et al., 2015). While Hanleybrown and colleagues (2012) suggested that the backbone should be a neutral facilitator, others have argued that to ensure equity, the backbone organisation must have a point of view that explicitly includes a focus on equity.

An equity lens should also be brought to shared measurement to enable collective impact projects to have equitable outcomes and improve inequities for groups experiencing disadvantage. Bringing an equity lens to shared measurement requires disaggregation of data to reveal disparities based on location, race, socio-economic status, gender, disability, age and other factors that may be important in a community. If data is not disaggregated, actions may be developed that are unsuitable for a particular population group, or a project may improve results for some groups but not others (LeChasseur, 2016; Williams & Marxer, 2014).

Although there are now many articles and resources that address equity and promote equitable practices within collective impact (e.g., Collective Impact Forum, 2016; Kania et al., 2014; Kania & Kramer, 2015), practitioners must know where to look for this information, and have the time to find, read and apply it (LeChasseur, 2016). This comes with the risk that equity becomes an add-on or optional extra, rather than a core element of collective impact.

Need for policy and systems change

Collective impact aims for "transformative" or "transformational" change. This is based on the premise that complex problems require a radical shift in the way they are solved, and the solutions themselves will both require and cause significant systemic changes. The system needs to change because "enhancing the current system most often gives us more of what we already have" (Born & Bourgeois, 2014, p. 137).

The collective impact framework is intentionally non-prescriptive when discussing the types of activities that sites should use to seek solutions to social issues; however, the failure to explicitly mention the importance of policy and systems change has been widely criticised (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016; Flood, Minkler, Lavery, Estrada, & Falbe, 2015; Forum for Youth, 2014; Himmelman et al., 2017; LeChasseur, 2016; McAfee et al., 2015; Wolff, 2016). It is generally accepted within public health that best practice interventions seek multi-level and multi-strategy change (Marmot, Friel, Bell, Houweling, & Taylor, 2008; Moore et al., 2014) and include strategies that seek changes in policies and systems (Himmelman et al., 2017). Seeking policy and systems change is also considered a fundamental strategy in community coalitions and many other frameworks for collaborative social change (Flood et al., 2015; Himmelman et al., 2017; Wolff, 2016).

To achieve population-level change; policy, systemic and environmental change is required (Graham & Weaver, 2016; Weaver, 2016). If this is omitted from a collective impact project, the scope of what can be achieved is limited. Collective impact projects that seek to address the social determinants of health or root causes of issues have potential to create sustainable change, but projects that focus on improved service delivery are more likely to alleviate symptoms or improve conditions rather than make sustained positive change towards reducing or eliminating social issues. Collective impact projects should maintain a focus on the systemic disadvantage that produces individual behaviours (LeChasseur, 2016) in order to avoid stalling strategies at the programmatic level (McAfee et al., 2015). They should also avoid "low-leverage" activities, such as service alignment through co-location, that are easy to implement but rarely result in improved outcomes (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016).

The complex issues that collective impact seeks to address such as poverty, disadvantage and poor outcomes for children are primarily caused by broad social and economic forces (Katz, 2007), or in public health terminology, the social determinants of health (Marmot, 2015, 2016). Given that the causes of these issues are primarily outside of the communities in which the impacts are felt, Katz (2007) suggests that the most appropriate tools to address these issues are "redistributive economic policies such as taxes, benefits, jobs, interest rates and international trade"(p. 21). While these may be outside the remit of most collective impact projects, collective impact sites should engage government and seek systemic and policy change in order to maximise their effectiveness (Forum for Youth, 2014).

Collective impact, public health and other collaborative social change efforts

Collective impact has been critiqued for failing to engage with and draw upon existing research and practice. Despite Kania and Kramer's (2011) claim that collective impact was developed through research, this seems to have consisted of a limited number of case studies and limited experience of collaborative change efforts (Himmelman et al., 2017; Wolff, 2016). Although portrayed in the foundational articles as an entirely new and novel approach, collective impact owes a legacy to the theory and practice of coalition building, community organising and community development (Christens & Inzeo, 2015; Himmelman et al., 2017).

There is a long history of work in the areas of partnership, collaboration, community development, coalition building and grassroots organisation that is supported by a considerable body of literature and theory and which is highly relevant to collective impact (Christens & Inzeo, 2015; Himmelman et al., 2017). There are also other models for collaborative change, such as the Community Coalition Action Theory (Butterfoss & Kegler, 2009) and the Power of Collaborative Solutions (Wolff, 2010), that Kania and Kramer failed to draw upon and acknowledge in their development and description of collective impact (Himmelman et al., 2017; Wolff, 2016).

There are some differences between these approaches, which have been pointed out by academics and practitioners; however, as the collective impact field evolves and diversifies, these differences appear to be becoming less marked. These differences are very similar to areas identified as missing from collective impact in initial criticism: failure to engage with community (Christens & Inzeo, 2015); failure to acknowledge and address the role of power and inequity (Christens & Inzeo, 2015; LeChasseur, 2016); and a focus on service-based solutions at the exclusion of seeking policy or systems change (Flood et al., 2015).

A further field of work that has been overlooked by the collective impact literature is that of public health prevention (Homel, Freiberg, & Branch, 2015). A public health approach seeks to prevent [health] issues from developing in the first place and is often framed as a four-step process: the issue is defined and measured; risk and protective factors are identified; interventions are developed, trialled and evaluated; and effective (evidence-based) strategies are scaled-up and disseminated (Sethi, 2013). It is recognised within public health, as it is in collective impact, that effective strategies seek to treat the cause of issues in addition to alleviating the symptoms, and in the case of complex problems and the social determinants of health, this requires multi-level action and multi-sectoral collaboration (Marmot, 2007). While the field of collective impact echoes this approach in some ways (e.g., using data to inform decision-making), the identification of risk and protective factors and the application of evidence-based strategies to address these are steps that could contribute to a collective impact project's ability to achieve population-level impact. There is a long history of community-based collaborative work in the public health field and a corresponding wealth of research and evidence. Collective impact could benefit from a closer alignment with this work.

Lack of community engagement

One of the most widespread and sustained criticisms of collective impact to date has been its failure to adequately address the need for meaningful community engagement and leadership (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016; Christens & Inzeo, 2015; Harwood, 2014; Himmelman et al., 2017; LeChasseur, 2016; McAfee et al., 2015; Raderstrong & Boyea-Robinson, 2016; Wolff, 2016). Without the full and meaningful engagement of community members, actions and solutions to issues may not be appropriate, acceptable or compatible with community needs or effective in the local context (Moore et al., 2016; Wolff, 2016). Changes may reinforce existing inequitable power structures (LeChasseur, 2016; Wolff, 2016) and consist of service-oriented improvements rather than the transformative change that is required to address the causes of complex issues (Brady, 2015; Cabaj & Weaver, 2016; McAfee et al., 2015; Wolff, 2016).

Research looking broadly at place-based and community change initiatives suggests that the effectiveness of these initiatives is likely to be enhanced through community engagement (Katz, 2007; Moore et al., 2016) but that meaningful community engagement can prove challenging for traditional hierarchical and professional-focused governments and service providers (Moore et al., 2016). This appears to be the case with collective impact. Initial documents focused on the role of "CEO-level individuals from key organisations" (Hanleybrown et al., 2012, p. 15), and although more recent publications have recognised the importance of community engagement (Collective Impact Forum, 2016), it remains a challenge for many collective impact sites (Roundtable on Community Engagement and Collective Impact, 2014). Despite some examples of effective community engagement in collective impact initiatives, the collective impact field is underdeveloped in this area (Raderstrong & Boyea-Robinson, 2016).

Meaningful participation from people affected by an issue can result in actions and solutions that are both better suited to community needs and more likely to be utilised by the community (Roundtable on Community Engagement and Collective Impact, 2014). In many cases, the people who would most benefit from services are the least able or likely to use them (Katz, 2007; Moore et al., 2016), and there are often significant differences between the people leading an initiative and the people whom the initiative is intended to benefit in terms of factors such as socio-economic background, education, race or ethnicity and employment status. This means that without community engagement, the leaders of these projects must rely on assumptions about what community members need and how it should be delivered (Raderstrong & Boyea-Robinson, 2016).

While recent literature and resources acknowledge the importance of community engagement in collective impact projects (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016; Collective Impact Forum, 2016; Weaver, 2014b), there is less consensus on what constitutes effective community engagement. This is not limited to the collective impact field, the whole community and social change sector is grappling with how and when to effectively engage with communities (Moore et al., 2016). It is suggested that effective community engagement requires a paradigm shift (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016; Moore et al., 2016) from a top-down managerial approach to an approach that brings together all stakeholders, including community members, as decision-makers and active contributors to the project. This shift is described by Harwood (2014) as a "turning outward" whereby the community becomes the focus of a change initiative rather than the organisations involved. Community in this sense is defined as the citizens of an area, with a particular focus on those who have lived experience of the issue the initiative is seeking to address.

For collective impact projects to undertake meaningful community engagement it must be an expressed priority, must be sufficiently resourced, and must be genuine and meaningful. That is, community members must be fully involved in decision-making at all levels of the project, and community engagement should not be limited to consultation on specified issues or communications and marketing campaigns (Harwood, 2014; McAfee et al., 2015). This is likely to require engaging community members with lived experience of issues to inform the initiative and building the capacity of community members so that they can contribute meaningfully to decision-making while also building the capacity of the collective impact initiative itself to be able to work effectively with the community (Raderstrong & Boyea-Robinson, 2016). Community engagement is likely to be most effective when the "context experts" (Raderstrong & Boyea-Robinson, 2016, p. 188), (community members and specifically people with lived experience of the issues the project seeks to address) are brought together with leaders and those with power (the "content experts") and space is created for meaningful conversation (Moore et al., 2014; Roundtable on Community Engagement and Collective Impact, 2014; Wolff, 2016).

When comprehensive and genuine community engagement takes place, collective impact projects are more likely to achieve transformational change for two main reasons: the shift in power that occurs as a result of having community members at the centre of collective impact initiatives (Christens & Inzeo, 2015), and the fact that community members are more likely to have transformative ideas about systems change rather than leaders who may be invested in existing systems and seek systems improvement rather than radical change (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016).

The effect of criticism on the collective impact framework

These are substantial and robust criticisms that have significant implications for the ability of collective impact initiatives to address the causes of social problems. To undertake a collective impact process that engages meaningfully with communities, prioritises equity and seeks policy and systemic change requires a substantial shift in the way the service sector operates. However, it is only through incorporating these elements into the collective impact framework, that collective impact sites are likely to fulfil their potential for transformational, population-level change.

Box 3: Logan Together

Logan Together is a "whole-of-city child development approach" (p. 2) located in Logan, Queensland, that is using the collective impact framework to improve outcomes for children, with a focus on the first eight years of a child's life (Logan Together, July 2016).

Established in 2014, Logan Together was the result of three factors: a long history of service collaboration in Logan; an exploration by services of how they could address the causes of social issues rather than the symptoms; and a summit in which community members and services expressed a desire for better opportunities for children and young people (Cox, 2016 [personal communication]).

Why collective impact

For Logan Together, the collective impact framework was able to articulate the barriers to improving outcomes for children and young people. While there is a significant amount of research that describes what needs to be done to improve outcomes for children, this knowledge is not always known within the practice community, nor is it clear how it can be implemented. Funding and service provision arrangements (including a fragmented service system and a lack of shared vision) provide further barriers to putting this knowledge into practice (Cox, 2016 [personal communication]).

Logan Together work within an "evolved" version of the collective impact framework that seeks policy change and is informed by meaningful community engagement (Logan Together, July 2016). They also supplement the framework with a range of other theories and practice frameworks: the life-course approach, prevention, citizen engagement and co-design, and an understanding of risk and protective factors (Logan Together, July 2016).

Structure, governance and action

Logan Together is funded by 12 different partners consisting of federal and state government, local organisations and philanthropic funders. The role of backbone organisation is played by the Logan Together Campaign Team. The team has skills in communications, project management, community engagement and data and systems analysis, and is supported by contract staff and skilled volunteers (Cox, 2016 [personal communication]).

The organisational and governance structures of Logan Together are complex, representative of Logan Together's aim to work across multiple sectors and at multiple levels. The key body is the Cross-Sectoral Leadership Table, which has members from the community, non-government services and all levels of government. There are also various chapters covering different priority areas that are responsible for supporting and implementing actions. Finally, there are inter-departmental committees at state and federal government levels that are identifying issues and seeking solutions to systemic barriers (Logan Together, January 2016).

Logan Together have developed a "roadmap" that outlines the policy and programmatic actions they intend to take to achieve their aims. The roadmap represents a shift towards prevention and early intervention via universal service provision with specialist supports provided to families that need extra help (Logan Together, 2015). The actions in the roadmap are based on data analysis and research evidence as well as community consultation. The campaign team recognise the tension inherent in this and are seeking to balance and combine these two approaches.

Get more information on Logan Together.

This case study was developed based on discussion with Matthew Cox, Director of Logan Together.

Evidence and evaluation

Evaluation is a complex and challenging area for collective impact. Shared measurement is one of the five core conditions of collective impact, and collective impact represents a shift towards data-driven decision-making; however, evaluation and measurement are consistently one of the biggest challenges for collective impact sites and practitioners. Given the foundations of collective impact in other community-based or place-based collaborative methodologies, and the many shared characteristics with these projects, successful projects in these other fields, particularly public health, suggest that the collective impact approach may be an effective strategy to address social issues.

The evidence base for collective impact

Developing an evidence base to support the development and implementation of collective impact projects is challenging. Like other community-based collaborative approaches, there are significant methodological challenges to evaluating collective impact, and collective impact has not been established long enough to develop an evidence base (Cortis, 2008; Moore et al., 2014). Collective impact is still evolving as an approach and has not yet "settled" into a framework or model that can be tested. In Australia, in particular, many projects are still in the early stages of development and have not yet established shared measurement systems (Salignac et al., 2017) nor had time for results to become apparent.

The emergent nature of collective impact means that there is not yet empirical evidence to demonstrate its effectiveness (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016; Christens & Inzeo, 2015; Gillam, Counts, & Garstka, 2016; Moore et al., 2014). Results from the United States and Canada, where collective impact is more established, have been mixed (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016). Although limited, there is some international and Australian evidence that place-based approaches can be effective (Wilks, Lahousse, & Edwards, 2015); however, there is not yet enough evidence to determine whether collective impact is an effective strategy for improving outcomes in the Australian context (Moore et al., 2014). Collective impact may be a "promising" approach that simply requires more testing (Flood et al., 2015).

While there is a lack of high quality evidence, particularly from Australia, to support collective impact, rigorous study designs on initiatives such as Communities That Care and PROSPER, in the United States, have demonstrated that place-based collaborative initiatives that share many characteristics with collective impact can achieve population-level change (Chilenski, Ang, Greenberg, Feinberg, & Spoth, 2014; Feinberg, Jones, Greenberg, Osgood, & Bontempo, 2010).

Challenges of evaluating collective impact

Collective impact is a data-driven process. Shared measurement is one of the five core conditions of collective impact, and collective impact initiatives require ongoing measurement and evaluation for continuous learning. However, fulfilling these research and evaluation requirements are some of the biggest challenges faced by stakeholders (Salignac et al., 2017; Weaver, 2014b). There are a number of factors that contribute to evaluation being a significant challenge for collective impact projects.

Collective impact projects are complex and dynamic (Moore et al., 2014); that is, there are multiple and intersecting strategies that change and evolve throughout the life of the project. Added to this complexity are changes in the context: people move in and out of an area and there are changes in demographics and in organisational, policy or funding environments that can complicate evaluation (Cortis, 2008; Parkhurst & Preskill, 2014). Evaluating complex community-based initiatives such as these requires significant investment in large-scale evaluations and in building evaluation capacity, something that has been missing from much Australian place-based work (Wilks et al., 2015).

Collective impact projects take a long time to establish and a long time for outcomes to become apparent (Graham & Weaver, 2016). Evaluation is time consuming and resource intensive (Cabaj, 2014) and there are many factors that can influence a site's ability to establish a shared measurement system (e.g., see Box 4). Cabaj (2014) suggests that simply establishing a shared measurement system often requires systemic change to overcome the siloed nature of data collection and measurement between sectors and stakeholders, and the myriad other challenges of using population-level data (Cortis, 2008). This combined with the challenge of getting agreement from diverse stakeholders on outcomes and indicators can delay the implementation and evaluation of collective impact projects (Cabaj, 2014).

There are additional challenges that come from the collaborative nature of collective impact. While traditionally evaluation isolates the effects of a single intervention and can attribute these to the organisation or program that caused them, collective impact projects have multiple stakeholders working together (Hanleybrown et al., 2012). This results in problems of attribution where stakeholders are unable to identify the outcomes of their individual contribution. This can have implications for funding and contractual obligations.

Evaluation requirements for collective impact

The emergent nature of collective impact strategies has two key implications for evaluation. First, as outlined above, the dynamic nature of collective impact makes traditional forms of evaluation challenging. Second, it means that collective impact projects rely heavily on evaluation to plan and implement their strategies. Responding to complex problems requires sites to implement a range of strategies and actions without knowing exactly what the outcomes of those strategies will be. This makes regular and ongoing evaluation essential so that sites can adapt, change or discontinue strategies as they determine what is effective in addressing the complex issues they have identified.

Ongoing process evaluation or evaluation methods such as developmental evaluation that explore how and why interventions are working is needed in addition to shared measurement systems that evaluate what progress is being made on population-level outcomes (Preskill et al., 2014; Weaver, 2014b). Furthermore, while much of the collective impact literature suggests that the primary purpose of evaluation is the learning and planning needs of collective impact practitioners, the role of evaluation in accountability to funding bodies and local communities is also important, as is the role of rigorous evaluation that can demonstrate causality in order to contribute to the evidence base for collective impact.

There are a number of resources available to support collective impact sites with evaluation; however, it remains an ongoing issue and it is often the condition that sites find the most difficult to implement (Weaver, 2014b). This is felt particularly in projects that have less resources (e.g., see Box 4). Anecdotal evidence suggests that both in Australia and internationally, where there are resources for evaluation within collective impact projects, the need for a shared measurement system and data-driven decision-making is overshadowing process evaluation and a formalised continuous learning process (Moore & West, 2016 [personal communication]; Weaver, 2014b).

Parkhust and Preskill (2014) suggested that the evaluation of collective impact projects needs to occur in three overlapping phases and utilise three different forms of evaluation:

- developmental evaluation to provide real-time feedback on strategies and actions and how they are being implemented;

- formative evaluation to evaluate the design and implementation of the initiative itself; and

- summative evaluation periodically or at the end of a project to examine a project's influence on systems and outcomes.

Evaluation that examines unintended outcomes is also particularly relevant (Cabaj, 2014).

Various methods of evaluation have been recommended for collective impact, primarily developmental evaluation or realist evaluation (Kania & Kramer, 2013; Moore et al., 2014; Parkhurst & Preskill, 2014; Walzer, Weaver, & McGuire, 2016) to provide information about how and why the project is having an impact, and Results Based Accountability to identify outcomes and indicators (Cabaj, 2014). It has been suggested that collective impact could learn from evaluation methods and strategies used by other collaborative, community-based work, (Christens & Inzeo, 2015), including in the area of public health.

Collective impact is taking place in a context where there is an increasing requirement for government-funded service providers to demonstrate that they are using evidence-based practices and programs (e.g., Department of Social Services, 2016), and what is considered credible is based on traditional hierarchies of evidence that prioritise clinical methods such as randomised controlled trials (Parker & Robinson, 2013). In place-based collective impact initiatives, randomised controlled trials may not be appropriate or practical (Cabaj, 2014) as the changes being sought are complex and multi-levelled, and it is difficult to restrict the intervention from some people while making it available to others. Drawing from the field of public health, Spoth and colleagues (2013) recommended mixed methods approaches that include "rigorous adaptive designs" together with community-engaged research methodologies such as participatory action research.

The Australian collective impact field must find a balance between the need to create an evidence base through scientifically accepted methods and meeting the information and evaluation needs of practitioners and communities working at the grassroots level to bring about change (Spoth et al., 2013). What is clear is that within the resource-limited environments of many collective impact initiatives, evaluation remains a significant challenge and there is a need for researcher-practitioner partnerships (Homel et al., 2015; Spoth et al., 2013) and greater investment.

Where is the Australian evidence base?

Despite the proliferation of projects, collective impact is still a new practice in Australia. Most Australian collective impact initiatives are not yet established enough to have had a measurable impact, and only a very small number are advanced enough to be evaluating outcomes (Graham & Weaver, 2016). Likewise, there is limited research and evaluation on other place-based initiatives in Australia. Fry and colleagues (2014) found that most Australian research examined effective implementation or effective support of place-based projects rather than evaluating long-term outcomes. In addition, these authors identified that there has been "minimal" investment in long-term research examining place-based approaches (Fry et al., 2014). These findings were echoed by Wilks and colleagues (2015) when they examined federally funded place-based initiatives in Australia - they found that high-quality evaluation that could determine causality was rare, and that greater investment was needed to enhance the evidence base.

The sharing of knowledge has been identified as a challenge for place-based work (Fry et al., 2014), and Fry and colleagues' (2014) research found that while there are examples of good practice, there is no mechanism to connect policy, research and practice, nor was there any peak body or organisation who was regularly facilitating dialogue between stakeholders working in this area. Collaboration for Impact1 is able to fulfil this role to a degree within Australia, however, Graham (2017 [personal communication]; Graham & Weaver, 2016) has also identified the need for collective impact in Australia to build an evidence base and share learning, as the majority of research and case studies that exist are from North America and there are important differences in the Australian context.

The extent to which Australian collective impact sites are demonstrating good practice with measurement and evaluation as described in the collective impact literature is unclear. Some sites have reported using developmental evaluation methodologies (e.g., Cox, 2016 [personal communication]; McCoy, Rose, & Connolly, 2016) but there is no published material that describes how this was done in practice or the effectiveness or outcomes of this methodology.

There is variation among Australian collective impact projects about both the degree to which they are using data to inform their strategies and decisions, and how data is being used to track their progress. While some sites have undertaken detailed data analysis and used this to inform their strategies and measure their progress (e.g., Batchler, 2015; Logan Together, 2015; The Maranguka Justice Reinvestment Project, 2016) other sites have undertaken process evaluation and are still developing shared measurement systems (e.g., Central Victorian Primary Care Partnership [CVPCP], 2015; Press, Wong, & Wangman, 2016).

Due to the early stage of development in Australia, evaluations undertaken to date on Australian collective impact initiatives have tended to describe how stakeholders are working together rather than outcomes at the population or programmatic levels.

Box 4: Blue Mountains Stronger Families Alliance

The Blue Mountains Stronger Families Alliance (SFA) operates across 27 settlements along the ridgeline of the Blue Mountains in New South Wales (NSW). It was formed in 2006 and was initially informed by service collaboration models from the United States. When Kania and Kramer's (2011) "collective impact" article was published, it resonated with the SFA members and collective impact was adopted as a guiding framework for the project.

The SFA aims to improve service delivery to children, young people and their families through the delivery of the shared Child and Family Plan (Stronger Families Alliance, 2010).

Structure and governance

The SFA consists of 46 member organisations, with strategic planning and decision-making delegated to an executive group. The executive group is made up of senior staff from relevant peak bodies and state government, not-for-profit organisations, mental health services, the youth sector and local government. Currently, there is no mechanism for community voice in decision-making. The SFA have identified that community buy-in is needed, and are currently considering options to include community representatives in SFA governance (Thomas, 2017 [personal communication]).

Backbone support is shared between the Blue Mountains City Council and Mountains Community Resource Network (MCRN). Actions are undertaken by three "implementation groups". These groups have overseen collaborative actions such as workforce development, school-centred community hubs, running supported playgroups, embedding child consultation as part of local government planning, and workforce development. To date there has been no focus on policy change.

The collective impact framework is supplemented by other practices and theories, in particular appreciative inquiry and a strengths-based approach (Thomas, 2017 [personal communication]), as well as positive organisational development and prevention and early intervention approaches. The Harwood approach to community engagement is currently being used to inform community consultation.

The SFA is a small-scale collective impact project with limited resources. While SFA have been successful at negotiating with NSW Family and Community Services Department for changed service agreements that have enabled the better resourcing of some projects, the region is not eligible for funding allocated for areas of disadvantage due to the mixed demographics of the area.

Evaluation

Shared measurement remains a challenge for the SFA. Resources for data collection and analysis are limited, and accessing data is difficult. Census data is collected too infrequently and is not localised enough, and the SFA have not been permitted to access local-area data collected by the NSW Government.

A process evaluation was conducted in 2014-15 that found the SFA has been successful at building service collaboration and enabling and supporting the development of evidence-based strategies. Evaluation to date has explored the collaboration itself and has not yet measured outcomes for children and families.

Next steps

Current priorities for the SFA are developing a shared measurement system and drafting a new Child and Youth Plan to incorporate a broader target group and focus. It is intended that the new plan will have a clearer focus on outcomes and outcomes measurement and some shifts in how actions are delivered and measured. Community consultation has been underway throughout 2016 to inform the redrafting of the plan, and it is anticipated that there will be a shift towards greater community involvement (Thomas, 2017 [personal communication]).

Get more information on Stronger Families.

This case study was developed through discussions with Kerry Thomas, Executive Officer, Gateway Family Services and founding member of the Blue Mountains Stronger Families Alliance.

1 Collaboration for Impact is an Australian-based collaboration community of practice with a significant online presence.

Implementing collective impact: opportunities and challenges

Effective implementation of collective impact is not a simple or easy process. Weaver (2014a) notes that the simplicity of the framework "belies the challenges that are embedded in the execution" (p. 17). There are frequent references in the collective impact literature about the "different way" of working that collective impact requires (Kania et al., 2014; Lilley, 2016; Senge et al., 2015; Weaver, 2016) but there is less instruction or tangible description of what this entails.

The functioning of the collective impact partnership has implications for the solutions and actions that are identified and selected and the way these are implemented. Factors such as governance, relationship building, leadership, resourcing and evaluation are critical to the success of collective impact initiatives. A review of the literature suggests that successful implementation requires attention to factors in addition to the five conditions, and a set of qualities and capabilities in practitioners and leaders that are different to those required by traditional program implementation or organisational management.

The importance of the backbone

Experienced practitioners working in collective impact, coalition building and collaborative community-based prevention work suggest that resourcing is one of the biggest challenges of collaborative work, and so the inclusion of the backbone is one of the greatest strengths of the collective impact framework (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016; Homel et al., 2015; McAfee et al., 2015; Wolff, 2016). Although initially the backbone function was conceived as requiring a separate organisation with dedicated staff (Kania & Kramer, 2011), the concept is now understood more broadly. As the two Australian case studies demonstrate, a backbone organisation can consist of staff from existing organisations with time dedicated to their role as backbone or can be a separate entity with dedicated staff. A backbone organisation can also be in the format of a steering committee (Hanleybrown et al., 2012). Although the collective impact framework has made clearer the necessity of a backbone organisation, resourcing remains a challenge for many sites (Hanleybrown et al., 2012).

Creating a "container for change"

Collective impact hypothesises that if the five conditions are in place then resources and solutions will "emerge"; that is, become identified and available. The role of collective impact practitioners is to facilitate this process. Cabaj and Weaver (2016) refer to this as "creating a container for change" (p. 9).

The structure that brings stakeholders together and the space this structure is able to create for discussion and learning is important. A clear governance and communication structure will bring stakeholders together and create an environment where they can collectively identify solutions and resources. Rather than creating a rigid strategy at the beginning of a project when solutions are not necessarily known, having a structure creates space for emergent solutions (Kania et al., 2014; Kania & Kramer, 2013) and provides the flexibility to test a range of strategies and discard what is not effective. Collective impact leaders need to involve stakeholders in an ongoing collaborative process of problem identification and solution generation. Engaging in this process without a strategy can be uncomfortable for many stakeholders (Kania & Kramer, 2013) and requires collective impact practitioners to build "tolerance for ambiguity and … trust in the process" (Gillam et al., 2016, p. 221). Without openness and tolerance for ambiguity, the emergent solutions may be missed (Senge et al., 2015). Graham and Weaver (2016) refer to this as creating the right "facilitative environment".

An effective structure is one that brings stakeholders together to enable the analysis of data and outcomes and allows for reflection and mutual learning that can build the capacity and authority of stakeholders to take action (Graham & Weaver, 2016; Kania et al., 2014). An effective structure also protects innovation through the creation of a "safe-to-fail" culture (Graham & Weaver, 2016). Without a robust structure, there is the risk that developing a strategic plan "becomes the outcome" (Walzer et al., 2016) and collective impact initiatives can default to programmatic responses or service-oriented reforms without spending adequate time analysing the problem and identifying and trialling solutions.

Adaptive leadership and systems leadership

The role of a collective impact leader in fostering emergence is different from the traditional way of solving problems in which a vision and plan are developed and the role of the leader or group is to persuade others to commit to the plan (Moore & Fry, 2011; Senge et al., 2015). The role of leaders in creating and sustaining the "container for change" is a challenging one and requires skills that are different from those required of organisational leadership (Wolff, 2016). There is a focus in the collective impact literature on "adaptive leadership" and "system leadership". Adaptive leadership creates the structures and space in which stakeholders can engage in mutual learning and problem solving, and system leadership is about cultivating a systems view (Senge et al., 2015; Weaver, 2016) that includes micro and macro perspectives of the issue (Weaver, 2016) as well as the factors and conditions that cause and influence the issue.

The "soft skills" of leadership - ensuring diversity, maintaining engagement, building trust (Kania et al., 2014), ensuring personal and organisational agendas don't dominate the process (Senge et al., 2015), navigating power differences and facilitating open dialogue - are of crucial importance. Although these are traditionally seen as secondary to the technical knowledge required of leaders, these adaptive leadership skills are essential for collective impact leaders. Salignac and colleagues (2017) research in Australia found that "relational factors" such as developing positive relationships, and building trust and honesty between partners were seen as essential to the functioning of successful collective impact projects. This same research also identified the importance of leadership, identifying the benefits of an adaptive leadership style that utilised elements of a "servant leadership" style. Apart from some notable articles (Senge et al., 2015; Weaver, 2016) the collective impact literature is limited in its discussion of how practitioners and leaders can build the unique leadership skills that collective impact requires.

Combining data, evidence and community knowledge

The collective impact literature suggests that solving complex social issues requires a combination of effective strategies and interventions rather than a single solution. Change is likely to be gradual and cumulative. In a good quality collective impact project, a range of interventions will be identified, trialled and evaluated. What is effective can be enhanced or scaled up, and what is ineffective can be rejected or changed. The role of regular data collection and a continuous cycle of action, reflection and learning is of key importance (Senge et al., 2015) and needs to be undertaken with a focus on outcomes.

The emergent nature of solutions does not preclude the role of research and evidence-based programs and practice within collective impact. Collective impact is a data-driven process, and data plays an essential role in understanding the social issue and in monitoring the outcomes of interventions. There is a place for evidence-based practice and evidence-based programs, or what Kania and colleagues refer to as "technical solutions" (Kania et al., 2014). Kania and colleagues (2014) suggest that these technical solutions "are often an important part of the overall solution, but adaptive work is required to enact them" (p. 5). This can be seen in the example of Logan Together (see Box 3), where there is existing research and evidence that identifies what is needed to improve outcomes for children but the systems and structures are not set up to facilitate this. Adaptive work is required to implement and monitor the right mix of interventions at a range of levels.

Even when some of the technical solutions are known, collective impact sites need to identify this research and examine how it applies in their context (Graham & Weaver, 2016). There is limited discussion within the collective impact literature that identifies the role of evidence-based practice or programs as part of solution generation, and while this has been included in Logan Together, for example in training educators and early childhood workers in the Abecedarian approach (Logan Together, January 2016), less information is available about the role that evidence-based programs and practices are playing in other collective impact initiatives. It has been suggested that the collective impact field would benefit from greater consideration and inclusion of evidence-based programs and practices (Homel et al., 2015).

Collective impact practitioners have identified tension when combining a data-driven, evidence-based approach with an approach that prioritises comprehensive community engagement (Cox, 2016 [personal communication]). Moore (2016) acknowledges this, suggesting that evidence-based practice is multi-dimensional and necessarily incorporates research evidence, client and professional values, and evidence-based processes. Utilising evidence-based practice in a medical context begins with relationship building between professionals and families and identifying desired outcomes before moving to solutions (Moore, 2016). In the context of collective impact, solving complex social issues would start with community engagement and collaborative identification of priorities and desired outcomes and then look to the research evidence to identify strategies to achieve the desired outcomes. Public health prevention also echoes this approach, undertaking research to explore the local context, identifying the needs and preferences of communities and practitioners, building support for the implementation of new and different (evidence-based) policies or programs and exploring the conditions in which implementation is likely to be most effective and have the greatest fidelity (Spoth et al., 2013).

Collective impact sites will increase their effectiveness by collecting and analysing data about the issue and context from a range of sources (including community members) and examining the research evidence for effective strategies, as well as including community members in the decision-making around these strategies.

Engagement and collaboration

Collaboration is essential when addressing complex problems. Conklin (2006, cited in Moore & Fry 2011) describes interventions to address wicked problems as necessarily being "a social process" (p. 10). Having a diversity of stakeholders working together enhances understanding of the multiple aspects and multiple causes of issues and increases the likelihood of cooperation to identify and implement solutions (Moore & Fry, 2011). Yet collaboration between agencies is difficult to do in practice and there is not yet a body of empirical evidence, particularly in Australia, to suggest that it is effective (Gillam et al., 2016; McDonald & Rosier, 2011). While this does not imply that it is ineffective, there is also little guidance from the collective impact literature that directly addresses the challenges of collaboration.

Huxham and Vangen (2004) have identified several challenges that commonly befall agencies seeking to collaborate: conflict between individual, organisational and collaborative aims; power imbalances between members; partnership fatigue; constant changes in context, leadership, governance and decision-making processes; and balancing task and process. Several of these challenges have been identified by collective impact practitioners (Gillam et al., 2016), notably that the requirement to develop a shared agenda can be a barrier to collaboration when there is conflict between the agency's goals and the goals of the collective impact initiative (Gillam et al., 2016; Milward, Cooper, & Shumate, 2016).

One of the challenges particularly felt by collective impact sites appears to be the issue of getting all the relevant stakeholders around the table, with Homel and colleagues (2015) observing that community organisations and government dominate many partnerships to the exclusion of the institutions that have most influence over children and families: schools, preschools, churches and families. Collaboration between sectors (such as education and the community sector) can be particularly difficult due to differences in culture and structure (Homel et al., 2015).

Engaging the right sectors of government has also been identified as a challenge for collective impact in Australia. While all levels of government are represented in collective impact projects in Australia, the government departments that are represented can have a significant influence over the actions and solutions that the project generates. The departments most often represented in collective impact projects are the families, communities or welfare departments, yet collective impact seeks to address the causes of social issues rather than treat the symptoms, and the causes of social issues often lie outside the remit of these departments, in the areas of housing, transport, education or employment (Moore & West, 2016 [personal communication]).

Collaborating across different sectors and departments is challenging and requires practitioners to develop new skills and practices (Moore & Fry, 2011). Effective collaboration with community members and stakeholder groups that have vastly different needs and ways of engaging is also challenging and requires significant capacity building both among practitioners and organisations to be able to effectively engage and collaborate with community members, as well as of community members themselves (Moore et al., 2016).

Supportive environments: the role of government and funders

There is a range of external factors that influence the ability of a collective impact initiative to be effective. A number of changes have been identified that need to take place in the public sector and funding environment to enable effective responses to complex problems. Collective impact initiatives can be resource-intensive and are likely to require flexible financial systems and funding models that enable the pooling of budgets (Head & Alford cited in Moore & Fry, 2011) and increased flexibility from funders that focuses on outcomes rather than outputs and allows for a nuanced understanding of contribution rather than prioritising accountability (Forum for Youth, 2014; Kania & Kramer, 2013). In addition, flexible organisational structures are required to enable staff to participate both in the collective work as well as the work of their own organisations, and organisations and funders must shift from a risk-averse culture to a culture of collective learning (Head & Alford cited in Moore & Fry, 2011).

There is a significant role and challenge here for governments. Graham (2017 [personal communication]; Graham & Weaver, 2016) suggests that there are signs of the start of a shift in Australia, with governments in some areas shifting from "contract management" to an "enabling" role where resources are being repurposed to support collective work, and the beginnings of policy change are being seen in some departments. There is significant work required to cement and scale-up these developments. One example at local government level is Burnie Works in Tasmania, where the Burnie City Council is using a collective impact approach to achieve its long-term vision for the city (Burnie City Council, 2010). Collective impact has been successful at creating an "authorising environment" (Graham, 2017 [personal communication]) where sites build engagement with governments and service providers at every level from community-facing workers up to senior management, and this engagement creates an environment in which there is greater flexibility in contracts and funding requirements, and staff have greater flexibility to respond to the needs of the community. Government, funders and contract managers also have a role in enabling the "safe-to-fail" culture that protects innovation and experimentation (Graham & Weaver, 2016) and enables the sharing of knowledge.

Discussion: Considerations for practice

The collective impact framework has undoubtedly resonated with practitioners and communities both in Australia and internationally (Born & Bourgeois, 2014; Graham & O'Neil, 2014; Weaver, 2014a). While not always explicitly acknowledged, collective impact builds upon decades of experience of collaborative, community-based work (Gemmel, 2014). It provides a "clear and concise way" of describing collaborative work (Weaver, 2014a, p. 11; 2014b) in language that is recognisable to practitioners, has brought new focus and enthusiasm to collaborative work, and has made clear the resources required to undertake this work (Wolff, 2016).

Collective impact is in the early stages of development as a framework for change (Weaver, 2014b) and the evidence base to support its adoption and implementation is yet to emerge. There have been some calls for further testing to enable the framework to evolve before widespread adoption (Flood et al., 2015; Gemmel, 2014; McAfee et al., 2015; Wolff, 2016). The limitations of the evidence base are exacerbated by the challenges of evaluating complex and dynamic community-based initiatives.

As it currently stands, the five conditions of the collective impact framework are a useful way for practitioners to conceptualise and frame their collaborative work, and have been found to provide organisations with a "blueprint" for addressing complex social issues (Salignac et al., 2017). They leave "a great deal of space for individual or community interpretation" (Weaver, 2016, p. 281), however, and alone do not provide sufficient guidance to enable practitioners to achieve population-level impact (Kania et al., 2014; Kania & Kramer, 2015). Implementation of the collective impact framework poses many challenges, not least that it requires practitioners to lead and work in a way that is different to current practice.

If taken as a whole, the collective impact literature is considerably richer and more complex; however, the additional resources are "often overlooked" (Weaver, 2014a). The failure of Kania et al. (2014) to update the five conditions of collective impact increases the likelihood that collective impact will be adopted as a strategy without the inclusion of the other factors that are likely to increase the effectiveness of collective impact to address complex social issues.

If the criticism of the original five conditions is not addressed and, in particular, if collective impact initiatives do not engage meaningfully with community members and seek policy and systemic change, then these initiatives may be limited to improvements to services or service delivery rather than achieving transformative change that addresses the causes of complex social issues (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016; Wolff, 2016). Cabaj and Weaver (2016) conceptualised this as the shift from a managerial approach to a "movement building" approach. While a holistic, accessible and coordinated service system would benefit many children and families, it is still treating the symptoms of issues rather than addressing the causes of these issues (e.g., poverty) that result in poor outcomes for children and families (Moore & West, 2016 [personal communication]) and provides a less sustainable solution.

"Evolutions" of the collective impact model such as the Tamarack Institute's Collective impact 3.0 (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016), or other models for collaborative work such as the Community Coalition Action Theory (Butterfoss & Kegler, 2009) may be a better choice for community change practitioners (Flood et al., 2015), or may be required to supplement collective impact's five conditions. Both the theory and practice of collective impact would be strengthened by drawing upon related fields such as coalition building, community development and public health prevention. The case studies in this paper provide examples of how collective impact sites are supplementing collective impact with a range of other theories and practice frameworks.

Conclusion

The rapid adoption of collective impact in Australia and overseas is testament to the fact that current responses to the complex issues of contemporary families and communities are inadequate, and that a holistic and coordinated response resonates with practitioners in the social services sector.

Collective impact is one possible framework for a place-based response that is in line with our current knowledge of the most effective way to address complex social issues; however, it requires further development and evaluation. Collective impact has brought to the field of collaborative, community-based work an understanding of the complexity of social issues and the language with which to discuss them (Graham & Weaver, 2016), and clarified the resources required to undertake this work. If practitioners engage fully with the resources and literature of the collective impact field and supplement this with theory and practice from related fields, collective impact provides a promising framework for effective resolution of complex social issues.

References

- Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS). (2015). Inequality in Australia: A nation divided. Strawberry Hills, NSW: ACOSS.

- Batchler, K. (2015). Local data as a platform for action for families: Brisbane's 500 lives 500 homes collective impact campaign. Parity, 28(7), 18.

- Born, P., & Bourgeois, D. (2014). Point/Counterpoint: Collective impact. The Philanthropist, 2014(26), 1.

- Brady, S. (2015). Building many stories into collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review.

- Burnie City Council. (2010). Collective Impact Burnie. Retrieved from <www.burnie.net/Community/Community-Support/Collective-Impact-Burnie>.

- Butterfoss, F., & Kegler, K. (2009). The community coalition action theory. In R. DiClemente, R. Crosby, & M. Kegler (Eds.), Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. San Francisco: John Wiley and Sons.

- Cabaj, M. (2014). Evaluating collective impact: Five simple rules. The Philanthropist, 26(1), 109-124.

- Cabaj, M., & Weaver, L. (2016). Collective Impact 3.0: An evolving framework for community change. Canada: Tamarack Institute.

- Chilenski, S. M., Ang, P. M., Greenberg, M. T., Feinberg, M. E., & Spoth, R. (2014). The impact of a prevention delivery system on percieved social capital: The PROSPER project. Prevention Science, 15, 125-137.

- Christens, B. D., & Inzeo, P. T. (2015). Widening the view: situating collective impact among frameworks for community-led change. Community Development, 46(4), 420.

- Collective Impact Forum. (2016). Collective impact principles of practice. Retrieved from <collectiveimpactforum.org/resources/collective-impact-principles-practice?destination=node/7566>.

- Cortis, N. (2008). Evaluating area-based interventions: The case of "Communities for Children". Children and Society, 22, 112-123.

- Cox, M. (2016 [personal communication], 24 November). [Personal communication].

- Central Victorian Primary Care Partnership (CVPCP). (2015). Go Goldfields Alliance Evaluation Report 2012-2014. Maryborough, Victoria: CVPCP/Go Goldfields.

- Department of Social Services (DSS). (2016). Families and Children Expert Panel. Canberra: DSS. Retrieved from <www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/families-and-children/programmes-services/family-support-program/families-and-children-expert-panel>.

- Feinberg, M. E., Jones, D., Greenberg, M. T., Osgood, D. W., & Bontempo, D. (2010). Effects of the Communities That Care model in Pennsylvania on change in adolescent risk and problem behaviours. Prevention Science, 11, 163-171.

- Flood, J., Minkler, M., Lavery, S. H., Estrada, J., & Falbe, J. (2015). The Collective Impact Model and its potential for health promotion: overview and case study of a healthy retail initiative in San Francisco. Health Education & Behavior, 42(5), 654-668.

- Forum for Youth. (2014). Collective impact for policymakers: working together for children and youth. Retrieved from <forumfyi.org/files/collective_impact_for_policymakers.pdf>.

- Fry, R., Keyes, M., Laidlaw, B., & West, S. (2014). The state of play in Australian place-based activity for children. Parkville, Victoria: Murdoch Childrens Research Institute and the Royal Children's Hospital Centre for Community Child Health.

- Gemmel, L. (2014). Collective Impact. The Philanthropist, 26(1), 3-10.

- Gillam, R. J., Counts, J. M., & Garstka, T. A. (2016). Collective impact facilitators: how contextual and procedural factors influence collaboration. Community Development, 47(2), 209.

- Graham, K. (2017 [personal communication], 9 February). [Personal communication].