Planning for evaluation II: Getting into detail

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

Introduction

There are three keys to conducting a successful evaluation: planning, planning and planning. When you have decided to do an evaluation, and have an idea of the general processes and some of the key issues involved, you need to get down to the nitty gritty of evaluation - the why, who, what, when, where and how. The focus of this resource is on actually doing the evaluation; in particular, the small, vital tasks and issues that need to be addressed to ensure the evaluation goes smoothly.

In this resource, the aim is to prompt thinking and action on the simple or minor issues and tasks that can quickly derail an evaluation if not addressed early in the process. Remember, evaluation (especially impact evaluation; see Evaluation and Innovation in Family Support Services) is concerned with establishing that your program or intervention is the source of any changes observed in participants. For you to be able to say this, each step in the evaluation must be properly executed. By thinking through the why, who, what, when, where and how of conducting an evaluation, many of the possible sources of derailment can be avoided. Doing this will highlight the protocols and procedures that you need to put in place, and what will be needed to resource them adequately. Close monitoring of the process (see Box 1 & 2) will then allow you to identify, anticipate and deal with minor problems.

Box 1: Monitoring the evaluation

To make sure that the data collection is proceeding according to plan, it can be worthwhile contacting a small, random sample of respondents to check that the questionnaire or interview was conducted according to the established protocol:

- Was the need to collect the information adequately explained to participants?

- Did participants understand what they were being asked to do?

- Did participants understand they could decline to participate?

- Did they understand what is meant by informed consent?

- Did they understand the questions?

- Were they able to follow the instructions?

Box 2: Sticking to the rules

Systematic data collection is vital for the integrity of the evaluation. If certain processes are allowed to vary or are ignored, at the very least the evaluation team will be dealing with missing data, which can negatively affect the statistical analyses. At worst, the data and thus the evaluation may be rendered meaningless if the rigour of the evaluation, of which systematic data collection is an integral part, is compromised. Therefore, resources may need to be allocated to training and the ongoing monitoring of staff across all levels of the agency or organisation so that they understand not only the need to evaluate programs but also the need to closely follow evaluation procedures.

Some ways in which the rules might be broken are:

- not collecting data at the scheduled time points - e.g., collecting in week 3 of a program instead of week 2, or at the end of a session instead of at the beginning; or collecting data at different times for different people;

- allowing (or at least, not taking steps to prevent) interaction between program participants and those in your comparison or control group;*

- there is no or little agreement between evaluators on how qualitative survey responses will be “coded”;*

- letting one or two focus group participants dominate discussions, which can mean the full range of views is not represented in your data;* and

- allowing a lack of consistency in the way questions are asked or methods applied.

* Refer to Planning for Evaluation I: Basic Principles.

Why? Why are you evaluating this program?

As noted in Evaluation and Innovation in Family Support Services, there are a variety of reasons for evaluating programs. One reason is to determine whether the program benefits its clients, which parts of the program work, who it works for, how it works, and how well it works. Evaluation can provide the evidence needed to:

- support new or continued funding;

- address the requirements of the funding agreement;

- secure community and stakeholder support;

- improve staff performance and management;

- add to our understanding of how different factors (demographic, geographic, community, organisational) affect program outcomes; and

- contribute to the broader evidence base about what does and does not work in a particular type of program with particular kinds of participants.

Who? Who is to provide the data, and who will collect it?

Who will you collect data from? This will usually be obvious: if the program is for individual participants, then data would be collected from those participants. For example, for a program designed to offer strategies for helping individuals deal with mental illness, the participants will be the primary data source. However, it may be helpful to gather information from other sources so that you get an indication of whether and how the participant is applying (or not) the strategies outside of the program context. Common sources might include:

- partners or spouses;

- immediate family members, including siblings;

- extended family members, such as grandparents;

- teachers (especially when the program is focused on children in preschool or school);

- friends or co-workers; or

- other service providers.

If a program is aimed at children, then valuable additional data might be obtained from their parent(s) and teacher(s). Similarly, if participants are couples, data should be collected from both partners. Where family groups are involved, each member should have the opportunity to contribute information about their own experiences and their view of the impact of the program on themselves and their family. An issue for the evaluator is how to manage the collection of this amount of data.

On the face of it, there may not seem to be much involved in gathering data from other sources, but there are a number of associated administrative tasks that will need to be resourced and which have implications for agency staff:

- How will you contact participants and who in the agency will make the contact? Will the contact be via phone only, or will letters also be sent?

- What information will they need? - An information sheet will need to be created to tell participants about the program and why you are seeking their input, and their informed consent (perhaps written) will be needed before any data can be collected from them.1

- What will they be asked about? - A suitably worded questionnaire or interview (and other associated documents, such as cover letters) will need to be developed, based on the program objectives and the evaluation data to be collected from the participant.

There are also ethical issues associated with obtaining data from persons other than the participant. You will need to think about whether primary participants have the option of nominating who you can contact and/or specifying those you can not contact, and about obtaining from those third parties their agreement to preserve the confidentiality and privacy of the primary participant.

Consideration will also need to be given to who will actually collect the data. Four key issues arise immediately:

- If the data are to be collected at the time the program is being run, will the educator/counsellor/facilitator administer the questionnaire or will the evaluator (who might be an external consultant)2 attend the program to recruit participants and gather the data?

- Rapport can be critical to obtaining good quality data - Is there a good rapport between the evaluator/facilitator and the participants?

- Is there time in the program schedule to allow for participants to provide their data or will time need to be added to the first and/or final sessions (or sessions in between)?

Some participants may respond differently, depending on who is asking for information, perhaps because they are reluctant to provide negative feedback. An independent evaluator may be more likely to elicit balanced feedback on a counsellor or therapist than the counsellor or therapist themselves, even if the counsellor leaves the room while the client completes the feedback sheet. A perception that the person collecting data is an authority figure or a representative of the government may also influence participants' responses.

In some situations, it may be necessary to consider adapting the scheduling of appointments, sessions or programs to include time for the counsellor/educator/facilitator or the external evaluator to collect the evaluation data.

Regardless of who actually collects the data, it is critical that anyone involved (whether it be administrative or clinical staff, case workers, facilitators, counsellors, or educators) has a clear understanding of and commitment to the need for the evaluation, why the data are being collected in particular ways, and why it is essential that procedures for data collection are closely followed. It can be helpful to put in place a monitoring system in which a manager or the external evaluator observes or sits in on a session in which evaluation data are being collected. If respondents appear to be having difficulty understanding survey items or interview questions, this can be identified and corrected.

Preparing for your evaluation I: What does a completed evaluation look like?

Before starting to develop your own evaluation plan, it can help to look at how other service providers have gone about evaluating their programs, the types of data that were collected, how the findings were interpreted and reported, and so on.

A good source of examples of service-based evaluations are Practice Profile or Program databases. Practice or Program Profiles are a way of sharing information about a program or practice across a sector. Each profile describes the program and the theories and/or practices that underpin the program, outlines the methods used and the types of evidence collected, presents the results and interprets the findings. Practice Profile databases typically comprise programs that have been assessed as being effective; that is, the data demonstrate that the program objectives have been met. The evaluations may have been conducted solely by the service provider, or in some degree of partnership with an external evaluator.

Practice Profiles databases have been compiled for programs in a wide range of sectors. Examples that are relevant to the family support sector include:

- Promising Practices Network (US)

- Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development (US)

- Social Programs that Work (US)

- Parenting Interventions in Australia (AUS) <http://www.parentingrc.org.au/index.php/resources/parenting-interventions-in-australia>

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Promising Practice Profiles (AUS) <https://apps.aifs.gov.au/ipppregister>

- California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse (US)

- SAMSHA’s National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices (US)

The UK Centre for Excellence and Outcomes in Children and Young People's Services also reports on the key ingredients of effective local practices.

Preparing for your evaluation II: Evaluation in Indigenous and culturally and linguistically diverse contexts

Evaluating programs for Indigenous and culturally and linguistically diverse participants can present particular practical, logistical and ethical* challenges for evaluators. It is important that the evaluation component of the program is seen as part of the program package from the earliest discussions with the participants.

When talking with participants about the evaluation, be upfront about what is involved, what participants may be asked to do or say, what will be done with the findings, that the data will be presented in ways that do not identify individuals or specific families or communities, and so on. It is important to provide feedback sessions for participating individuals, families or communities to tell them about what the evaluation found and what it means for them, their family and community, and these should be incorporated into your dissemination strategy. Issues you will need to think through include:

- the design of the evaluation - how it can accommodate the particular conditions under which the evaluation will be run;

- accessing program participants in remote locations or outside of the agency;

- data collection - whether the data be collected by someone from the particular community or who speaks the language;

- the type of data that can be collected - using observational techniques and interviews to collect qualitative data may provide better and more accurate information;

- the time frame in which the evaluation can be done - allow time for relationship-building;

- using culturally-appropriate measures - make sure your instruments have been adapted for use with the particular Indigenous or cultural group; and

- checking and re-checking translations of survey items - ensure they are accurate and measure what you intend to measure.

If conducting the evaluation some time after the program has been completed, there may be some challenges in finding or making contact with the participants. For Indigenous participants, it may be useful to consider including the services of a "cultural broker" in your planning. A cultural broker can act as an interpreter, but their role can also be quite broad and include facilitating two-way interactions between evaluators and Indigenous participants and their families (Michie, 2003).

* For further information about informed consent, see Evidence-Based Practice and Service-Based Evaluation.

** See also Dissemination of Evaluation Findings.

What? What will you actually measure?

What attributes, knowledge, skills, attitudes, behaviours, feelings, or relationship and demographic characteristics will you measure?

What is measured and how it is measured are tied directly to the program objectives. These must be specific and measurable (see Planning for Evaluation I: Basic Principles) and be able to provide you with the evidence you need. Part of this process involves operationalising what you intend to measure. This means framing the concept or dimension or characteristic in terms of the actual data that will be gathered; hence the need to be very clear about exactly what the program is intended to change. Below are some examples of how a program objective might be operationalised, and the possible wording of the corresponding objective.

| The intention of the program might be to: | Which might be operationalised as: | And an objective might be worded: |

|---|---|---|

| Improve adolescent wellbeing | Changes in participants' self-esteem and/or social connectedness | At the end of the program, participants will report significantly improved self-esteem as measured by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. End-of-program levels of self-esteem will be maintained at 6-month follow-up |

| Improve couple relationship functioning | Changes in participants' levels of caregiving and/or conflict behaviours and/or intimacy | After completion of the program, partners' scores on the Conflict Tactics Scale will reflect significantly less hostility and aggression. Lower levels of hostility and aggression will be maintained at 6-week follow-up |

| Increase engagement of Indigenous clients in services offered in a particular location | The number of Indigenous clients accessing specific services (e.g., libraries, health centres) before and after engagement initiative | The number of Indigenous visitors to the maternal and child health centre will increase by 20% within one year of the implementation of the initiative |

| Improve the psychological wellbeing of drought-affected families | Changes in scores on standardised measures of depressive symptoms, couple communication, parent-child relationship, overall family functioning; family members' views on family dynamics, types of interactions, relationships, etc. | Family members' scores on the Beck Depression Inventory will indicate significantly lower depression after attending the program compared to before. Reduced depression symptoms will be maintained at 12-month follow-up |

| Encourage respectful relationships among adolescents | Changes in attitudes towards violence in relationships | At the end of the program, participants will be able to name at least three acceptable and three unacceptable behaviours in relationships |

Figuring out how to actually measure your objectives may take a little time. Most constructs - ranging from attitudes, experiences, social, cognitive, emotional and physical make-up and functioning, through to clinical symptoms and conditions and behavioural patterns and problems - are best measured using well-known and well-regarded3 inventories or scales that have been used and reported on by other evaluators or researchers, and are easy to use with the target group. If a tool exists to measure what you want to measure, there is no need to create a new one.4 Journal articles reporting studies in which an instrument has been used are useful sources of information, and there are also compilations of instruments available in libraries and online. Appendix 1 provides a list of such sources. Designing survey and other instruments to measure specific constructs can be a complex and time-consuming undertaking. Using existing instruments is a more efficient option, as long as the instrument you choose has been tested and its validity and reliability have been established for the group you intend to survey.

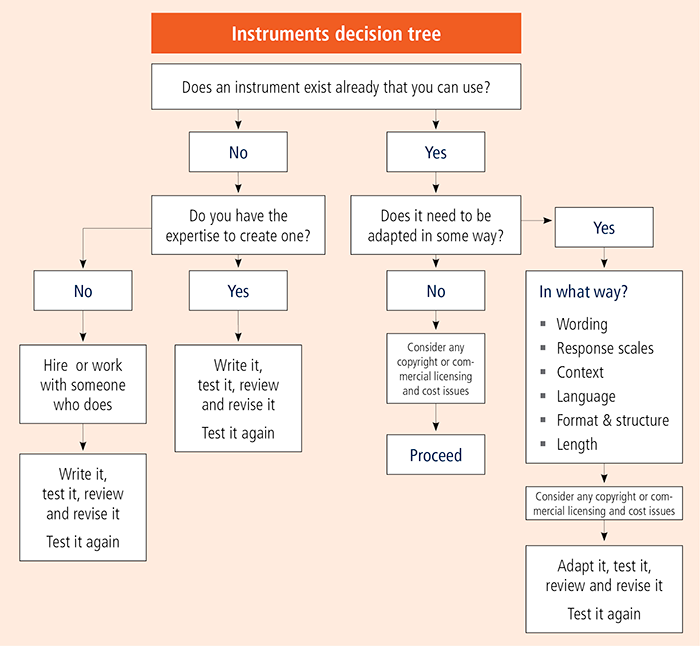

By using an established instrument you are contributing to its evidence base. You may, however, need to adapt an existing tool to the context in which you will use it (subject to any copyright restrictions). For example, if you want to use a scale designed for employees in an educational setting in a different kind of organisation, you will need to make sure the items make sense in the new context. Likewise, instruments developed in other countries and cultures may use language with which your participants are not familiar. Any amendments you make should not change the content of the items, because you might end up measuring something other than what you intended (see Box 3). Pilot testing of the amended items and checking their meaning and understanding with a separate, small group of participants will help to confirm that you will obtain the information you require. Specify the changes or adaptations in the evaluation report so that others can assess your actions. The instruments decision tree (see Figure 1) sets out the decisions you may need to make about what tools you might use to gather the data.

Figure 1: Hierarchy of evaluation designs and data collection methods

Box 3: Adapting established instruments: Some words of caution

Think carefully before adapting an existing instrument, as it may no longer be valid when used in a context, or for a client group, for which it was not intended. Developing instruments to measure aspects of a person's personality, mental health, psychological state, coping strategies, communication styles, and a myriad of constructs is a science in its own right, called psychometrics. A great deal of effort goes into ensuring that instruments measure what they are intended to measure, and do so accurately.

Two of the key characteristics of a good instrument are validity and reliability. These are described in Box 4. When an instrument is used in evaluation or research, details of its reliability and validity should be provided in the report so that the adequacy of the instrument can be assessed by the audience. It is important to read the literature about the tools used to evaluate your objectives to make sure they will provide you with the data you need.

Box 4: Reliability and validity

Validity

A valid measure is one that measures what it is intended to measure. This may sound obvious; however, it can sometimes be difficult to achieve. For instance, clients' reports of their satisfaction with a behaviour change program are not a particularly valid measure of the effect it had on their behaviour - it may tell you that the client enjoyed the program, but not whether it was effective in changing their behaviour. There are several types of validity that need to be considered. If you have used an established instrument, these are likely to have been addressed by the authors, or otherwise documented in research articles where the measure has been used or discussed. If you have created a new instrument, then you will need to assess and report on its validity.

Reliability

A reliable measure is one that, when used repeatedly under the same conditions, produces similar results. For example, if nothing else has intervened, a set of weighing scales should give the same reading every time a one-kilogram bag of flour is placed on it. When dealing with measures of psychological constructs, it can be difficult to assess the reliability of a measure. If you are using an established measurement tool, you can refer to reports of its reliability in the research literature. If you are recording the occurrence of particular behaviours, having more than one observer recording and coding the behaviours offers a way to determine reliability - by comparing the level of agreement between the observers' ratings. However, thorough preparation and training of the observers and clearly defined categories of behaviour are required to optimise the inter-rater reliability of your data.

Useful resources

In practical terms, there may need to be a trade-off between the amount of data you would like to collect and what is actually feasible within the context of the program. For instance, you may want to use the longer, more comprehensive measure of the behaviour of interest, but since that may take too long and/or place undue burden on the participants, you may need to find and use a shorter version. Similarly, where there are several aspects to what you want to measure - say, family functioning - it may not be possible to measure them all.

Examine each dimension closely in relation to the purpose of the program, and decide which will provide the better test of your objectives - and that you can actually assess. It is important to be transparent in doing this, so explain your reasons for selecting the particular aspects you measure in your evaluation report (see Dissemination of Evaluation Findings).

When? When should data collection take place?

One of the considerations in evaluating a program is the burden that completing questionnaires or participating in interviews places on participants. The timing of the data collection is important because you may be asking participants for information at a time when they are stressed or vulnerable. It may be worth considering whether any, and how much, data related to the evaluation is already, or can be, collected at intake. This might be a single question that can be compared to later reports. For example, you may wish to ask a single question about the overall severity of the primary issue or problem at intake and compare this to responses to the same question at the beginning of the first session (which might take place several days or some weeks after the initial contact or registration) and at the end of the final session. If evaluation data are to be collected at intake, make sure that additional time, if needed, is added to the intake process.

Some options for when you might collect your data:

- at registration/intake;

- on arrival for first session/appointment;

- at some point during the program - the beginning of the first session, or after three sessions;

- at the end of the final session;

- a week after the end of the program;

- a month later;

- six months later;

- a year later; and/or

- five years later.

If you are planning a pre- and post-test evaluation, then the first data will need to be collected close to the time the participants enter the program or service. If you have included comparison or control groups in your design, then to preserve the pre-program similarities between the groups, data for both groups must be collected at approximately the same times (as close as practicable), or at the same points in the process. Procedures need to be in place to ensure that the data can be gathered at the appropriate times. This may require adjustments to staff workloads or work plans, since failure to plan for these activities can hold up the evaluation.

Where follow-up data are to be collected beyond the time frame of the program, provision must be made for maintaining or re-establishing contact with past participants. This may involve creating new or adapting existing databases, both of which could require the contribution of administration or operational staff outside of the evaluation team. Where long-term follow-up (say, more than one or two years) is planned, a system may be required by which contact is made every, say, six months so that participants' current contact details can be confirmed or updated. This could be done perhaps by phone, or a postcard requesting confirmation by return post, or contacting the second contact person nominated by the participant at intake/registration. Very little data need be recorded at this time, since the purpose is primarily to maintain contact with participants. However, depending on the program, it may be useful to include one or two relevant items. For example, this would be a good opportunity to confirm the marital or relationship status of couples who previously participated in a relationship education program.

Participants' consent to be contacted for follow-up once their participation in the program is complete will also be required.5 This needs to be established early in the process; it is critical to be up front about what the evaluation means for the program participants. Some will agree to provide evaluation data now, but they may baulk at the prospect of being contacted for follow-up data collection at various intervals in the future.

Where? Where should the data be collected?

Generally, evaluation data will be collected where the program takes place. In some cases, however, this can be a somewhat artificial environment that may influence the way participants respond. It may be useful, instead, to gather data about the participant in a more natural setting, such as their home or school, or even a public place where the participant feels comfortable, such as a park or coffee shop. When working with children, permission will be needed from the school administration to observe a child at school, even if the parent/guardian has already consented, and this may take some time to obtain. Depending on the age of the child, they should also be given the opportunity to provide their own informed consent.

You might also need to consider whether the occupational health and safety regulations concerning program or evaluation staff will apply to their collecting data away from the service environment. There may be, for instance, policies preventing agency staff from conducting home or other off-site visits alone. Public locations may be preferred in these circumstances. It may be necessary, as part of the planning for the implementation of the evaluation plan, to put safety/welfare procedures in place.

How? How will the data be collected?

Methods of data collection

How are you going to gather the data? Some options are:

- self-report questionnaires (including surveys, scales and instruments measuring things like mental health, attitudes, self-esteem, and so on);

- focus groups (group interviews); and/or

- individual interviews.

These techniques are common, and are further discussed in Planning for Evaluation I: Basic Principles.

Other options include:

- document analysis and analysis of case notes; and

- observation of participants

Document analysis and analysis of case notes

Document and case note analysis requires full access to the materials. The degree of organisation and completeness of the records will influence how well the evaluation goals can be achieved. Here too, issues of informed consent and protection of privacy are relevant. The practitioner concerned will need to be aware that their case notes will be used in the evaluation and provided with the rationale for their inclusion. Protocols will need to be put in place to de-identify the information held in the case notes.

Observation of participants

Observation of participants essentially requires the presence of the evaluator at the program, although video recordings may also be used. Observation of participants would usually occur with their informed consent, obtained formally (in writing) or informally (verbally) before the program commences. There would need to be a strong method-related reason for not letting participants know that they will be observed,6 but this is more likely to be an issue in research studies than in program evaluations.7

Using technology to facilitate data collection

It is worth thinking about how new and existing technologies can facilitate administration of data collection. As an alternative to completing questionnaires or other self-report instruments while attending the program, evaluation data can be provided online or by phone. Questionnaires can also be mailed out to participants to complete at home (this might be especially suited to gathering follow-up data).

Interviews traditionally have been conducted face-to-face, but, depending on the content of the survey, they can be done over the phone. For some surveys, the lack of visual cues makes using phone calls a less desirable option, but computer assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) is generally very effective. Technology offers further options for interviewing participants who may live in remote regions or are otherwise unable to meet in person (e.g., using Skype or other web-based videoconferencing software).

Other issues to consider when deciding how to gather the data include:

- Establishing the appropriateness of using a particular method for the type of client and the type of program. For instance, what method is best for gathering data from preschool-aged children, the elderly, or those with intellectual disabilities?

- Deciding what the best way is to collect data from Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander clients or those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Cultural factors may significantly affect the way in which participants respond to questions in an interview or in a questionnaire about their experience of a program. They may also be reluctant to speak openly in focus groups where there are members of their own community, particularly when that community is small or close-knit. Translation and interpreter costs may need to be factored in to your evaluation budget.

- Ensuring that the survey is pitched at the appropriate level of literacy of the potential respondents.

- Protecting data from possible contamination. For example, by having participants complete self-report instruments online or mailing them to their home, there is a risk that the responses will be less reflective of the participant. For example, you run the risk that couple program participants will discuss their answers with each other and change their responses in light of those discussions.

And finally … design and layout

One of the aspects of data collection that can be overlooked in the planning stages is the time and money required for the design and layout of the materials used. If a staff member or the external evaluator is to administer the scale or inventory and collect the demographic and other information, then less emphasis need be placed on this aspect. However, where participants themselves are completing a questionnaire, then attention should be paid to the presentation of the materials - in particular the ease with which they can be understood and completed. The materials should also look professional. Again, this part of the evaluation process requires "someone's" time and effort, and a line in an evaluation budget.

References

- American Evaluation Association. (n. d.). Instrument collections. Fairhaven, MA: AEA. Retrieved from <www.eval.org/p/cm/ld/fid=72>

- Australian Centre on Quality of Life. (2006). Personal Wellbeing Index [instruments]. Melbourne: Deakin University.

- Bordens, K. S., & Abbott, B. B. (1996). Research design and methods: A process approach (3rd Ed.). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company.

- Child Trends (2006). Early childhood measures profiles (PDF 3.6 KB). Washington, DC: Child Trends.

- Children of Parents With a Mental Illness. (2010). Evaluating your intervention. North Adelaide, SA: COPMI.

- Haswell-Elkins, M., Hunter, E., Wargent, R., Hall, B., O'Higgins, C., & West, R. (2009). Protocols for the delivery of social and emotional wellbeing and mental health services in Indigenous communities: Guidelines for health workers, clinicians, consumers and carers. Cairns: University of Queensland and Queensland Health. Retrieved from <www.uq.edu.au/nqhepu/index.html?page=110805&pid=0>

- Lippman, L. H., Anderson Moore, K., & McIntosh, H. (2009). Positive indicators of child wellbeing: A conceptual framework, measures and methodological issues (Innocenti Working Paper No. 2009-21). Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

- Michie, M. (2003, July). The role of culture brokers in intercultural science education: A research proposal. Paper presented at the Australasian Science Education Research Association conference, Melbourne, Australia.

- Touliatos, J., Perlmutter, B. F., & Straus, M. A. (Eds.) (2001). Handbook of family measurement techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Appendix 1: Sources of established instruments

- Lippman, L. H., Anderson Moore, K., & McIntosh, H. (2009). Positive indicators of child wellbeing: A conceptual framework, measures and methodological issues. Published by UNICEF's Innocenti Research Centre, this report discusses the need for positive measures of children's wellbeing, identifies and reviews existing and potential indicators of positive wellbeing, and discusses methodological issues in developing positive wellbeing indicators. It includes the data sources for the examples of measures included in the report, an annotated bibliography, and an extensive list of references.

- American Evaluation Association. (n. d.). Instrument collections. This page hosts a comprehensive list of links to sites and resources for evaluation tools and instruments recommended by members of the American Evaluation Association. Most are free to access, although some instruments may require registration or purchase.

- Child Trends. (2006). Early childhood measures profiles (PDF 3.6 MB). This very large, comprehensive collection of early childhood measures across several domains (including social-emotional, language, literacy, and cognition) includes background information, reviews, and citations for each measure.

- Touliatos, J., Perlmutter, B. F., & Straus, M. A. (Eds.). (2001). Handbook of family measurement techniques. This reference contains the items, scoring information, respondent instructions, references and psychometric properties of 976 instruments. Measures are grouped into marital and family interaction; intimacy and family values; parent-child relations; family adjustment, health and wellbeing; and family problems.

- Australian Centre on Quality of Life. (2010). Personal Wellbeing Index [instruments]. An Australian brief measure of personal wellbeing can be found at the Australian Centre on Quality of Life website. Parallel forms have been developed for use with adults, school-aged and pre-school children, and for people with intellectual or cognitive disability. The site includes information on the development and testing of the questionnaire, and instructions and guidance on its administration.

- Children of Parents With a Mental Illness. (2010). Evaluating your intervention. The Australian Children of Parents With a Mental Illness Initiative website includes a section on evidence and evaluation, including a number of measures of child and adolescent wellbeing, coping, self-esteem, and resilience.

- Haswell-Elkins, M. et al. (2009). Protocols for the delivery of social and emotional wellbeing and mental health services in Indigenous communities: Guidelines for health workers, clinicians, consumers and carers. This publication contains items for assessing social and emotional wellbeing of Indigenous people, including practice tips and strategies for carrying out the assessment and helping the client elaborate on their responses.

Footnotes

1. For further information about informed consent, see Evaluation and Innovation in Family Support Services .

2. Refer to Evaluation and Innovation in Family Support Services for further discussion.

3. That is, those that have been shown to have adequate validity(see Box 4).

4. Note that there may be costs, copyright and/or licensing restrictions attached to some established instruments, and some instruments can only be administered by a person with appropriate qualifications.

5. For further discussion of informed consent, see Evaluation and Innovation in Family Support Services .

6. Most commonly, participants may not be advised that they will be observed in order to avoid them altering their behaviour in response to the knowledge that they are being watched by someone outside of the actual program. If children are to be observed, consent will need to be obtained from their parents and, if they are old enough, the child themselves.

7. However, there may be provisions in your funding agreement that state that informed consent must be obtained, regardless of the method of data collection when evaluating funded programs.

This paper was first developed and written by Robyn Parker, and published in the Issues Paper series for the Australian Family Relationships Clearinghouse (now part of CFCA Information Exchange). This paper has been updated by Elly Robinson, Manager of the Child Family Community Australia information exchange at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.