Flexible child care and Australian parents' work and care decision-making

November 2016

Jennifer Baxter, Kelly Hand, Reem Sweid

Download Research report

Overview

It is commonly stated that there is a need for flexible child care to be available to parents especially for those who work variable or non-standard hours, given the 24/7 nature of today's labour market. But Australian and international research shows that parents' decision-making about work and child care is complex and varied. This research report explores how parents make decisions about work and care, especially when faced with shift work or inflexible job conditions.

We ask here, what flexible child care arrangements are families seeking, and are those arrangements available? We further ask what are the barriers to families accessing different models of flexible care? This research draws upon interviews with Australian parents, with many of them working as police or nurses and so directly able to discuss how their child care needs are met in a context of working variable or non-standard hours. This interview data is examined along with some national survey data, and also survey data from parents of children engaged with specific school-aged care services, to include the perspectives of other Australian families.

Key messages

-

Decision-making about work and care is complex, and varies considerably across families depending on work characteristics of parents, ages of children, family structure and the availability of child care options.

-

Many parents valued the way they could meet their care needs informally, covering the care needs themselves or with the help of extended families. This was especially so for care at non-standard hours including evenings, overnight and weekends.

-

Among parents working non-standard hours, formal care options were used and centre-based arrangements valued. The lack of flexibility in formal care was a challenge for these parents.

-

More difficulties with meeting child care needs were experienced in larger families and those living away from extended family such as in regional areas.

-

Parents often adjust their employment to allow them to meet their child care needs, through changing jobs or reducing work hours. This can allow parents to provide care themselves or minimise non-parental child care. For some this is their preference, while for others it is because child care is not available that would otherwise meet their child care needs.

-

Parents wanted access to a range of child care options to allow for changing needs, and had varied needs for children of different ages within the family.

-

Parents wished for improved access to flexible care, especially for variable shifts and for non-standard work hours. However, there was some lack of certainty that formal options could meet such care needs, with a high value placed on informal care solutions, despite being challenging to negotiate and requiring compromises to incomes, family time or careers.

Executive summary

It is commonly stated that there is a need for flexible child care to be available to parents especially for those who work variable or non-standard hours, given the 24/7 nature of today's labour market. But Australian and international research shows that parents' decision-making about work and child care is complex and varied. This research report explores how parents make decisions about work and care, especially when faced with shift work or inflexible job conditions.

We ask here, what flexible child care arrangements are families seeking, and are those arrangements available? We further ask what are the barriers to families accessing different models of flexible care? This research draws upon interviews with Australian parents, with many of them working as police or nurses and so directly able to discuss how their child care needs are met in a context of working variable or non-standard hours. This interview data is examined along with some national survey data, and also survey data from parents of children engaged with specific school-aged care services, to include the perspectives of other Australian families.

There were many different stories that emerged from this research. In some families, parents had adapted their work situation to fit the care they had available to them. This included changing work hours to part-time, moving jobs to one that did not involve variable shifts, or even taking a period of time out of employment. Such adjustments were necessary for some parents who knew that they could not find a care solution to otherwise match their work arrangements. Others made adjustments such as these as they wished to prioritise caring for children, at least for a time. Understanding this proved critical to understanding parents' needs for flexible care, which were actually already met within many families when we spoke with them because of the work adjustments that had been made.

It was also important to understand that many parents valued the ways they could meet their care needs informally, either by arranging their work schedules to cover care needs themselves or calling on the help of extended family, such as grandparents. While such options were not always easy, and not available to all families, informal care was especially valued at “non-standard” times, such as early mornings, overnight or even on weekends. Informal care was often used to supplement formal care options.

Formal care options were used by many families, and centre-based care was seen as particularly desirable for children approaching school age, because of the social and learning opportunities it gave those children. The downside of this type of care was that it usually lacked flexibility, such that parents were not able to vary their times to match varying rosters, and some parents had difficulties with the opening hours their service offered. Shift-working families would nevertheless use centre-based care, often with informal care or their own juggling of work schedules. Family Day Care provided another type of formal care, which could be more flexible than centre-based care and could operate at non-standard hours. While national statistics show this form of care is less often used than centre-based care, the parents in this study who used it, and who had access to flexible care as a result, were very positive about this as a solution to their care needs. Family Day Care was not available to everyone and, indeed, was not always offered with a high degree of flexibility, as educators are able to determine whether they wish to provide overnight or varying hours of care.

With much diversity in terms of need among parents, of central importance was the availability of a range of child care options, so they can choose the care that best suits their needs at a particular time. Parents generally did not feel this to be the case at present and, in particular, had difficulties accessing formal care options that could match varying rosters or be called upon for short periods of care when work hours did not quite align with their available (parental or non-parental) care arrangements.

In terms of the barriers, the lack of availability of care at the times that parents needed it was the greatest barrier. Some parents sought better flexibility in the workplace, as a means of being able to better address their work and care responsibilities.

Beyond this, workplace and family characteristics meant different parents had more or less success in meeting their flexible care needs. Family factors that proved challenging included having a larger family, and having children of both school age and under-school age, whose child care services might have different operating hours. Living away from extended family, or living in areas with more limited care options such as in regional areas also proved challenging for some.

Overall, many parents expressed a wish for improved access to flexible child care, especially for care to match variable shifts and non-standard work hours. However, there remained a lack of certainty about the degree to which formal care options would be taken up by parents who have already found solutions to their care needs through informal care or adjusting their own work patterns. Such solutions were often preferred over formal care by parents, despite being challenging to negotiate or requiring some compromises to incomes, family time or careers.

This research highlights that decision-making about child care is not straightforward but varied. Future development of child care policy, especially that which attends to care at non-standard hours, needs to be done with consideration of the ways in which parents make decisions about work and care, and the value placed on non-formal care solutions as well as that placed on formal care.

| Abbreviation | Name |

|---|---|

| ABS | Australian Bureau of Statistics |

| AIFS | Australian Institute of Family Studies |

| ASD | autism spectrum disorder |

| CALD | culturally and linguistically diverse |

| CCFT | Child Care Flexibility Trials |

| ECE | early childhood education |

| ECEC | early childhood education and care |

| FCCS | Flexible Child Care Study |

| FDC | family day care |

| HILDA | Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey |

| LDC | long day care |

| NGO | non-government organisation |

| OSHC or OOSH | outside-school-hours/out-of-school-hours care |

| SACS | School-Aged Care Survey |

1. Introduction

Families' use of and need for child care rarely diminishes as an area of policy concern, especially in the context of ensuring there is adequate and high quality care that supports parents' (in particular mothers') employment. Increasingly there is concern that the existing model of formal child care has not kept up with the more flexible and non-standard nature of employment, which means parents need child care outside of the hours of a standard nine-to-five work-week, or need flexible care that can be varied as work hours vary.

This report focuses on the extent to which parents use or need flexible child care, in recognition that the nature of the labour market may be increasing parents' demands for such care. By "flexible" child care, we are concerned with child care that matches work hours that are outside of standard hours or are variable. While interested in parents' access to such care as available through the formal child care system, such as long day care (LDC), outside school hours care (OSHC) or family day care (FDC), this research considers other ways families find flexible child care solutions. We consider how families use informal care, as provided by extended family, friends or neighbours. This type of care is expected to be particularly valuable for families who need flexible care, as this care is generally highly valued by parents (Wheelock & Jones, 2002), especially for young children (Riley & Glass, 2002). Consequently, it is not necessarily used only because of a lack of availability of formal care options. Further, some parents manage their employment with no child care at all, that is, they rely on parent-only care (Baxter, 2013b; Gray, Baxter & Alexander, 2008). As with informal care, for some this may be due to a lack of availability of other options, while for others it may be the preferred care solution, to avoid relying on non-parental child care.

Specifically, this report explores the following questions, using new survey data on this topic:

- What flexible child care arrangements are families seeking, and are those arrangements currently available?

- What are barriers to families accessing different models of flexible care?

The research makes use of data collected for the AIFS evaluation of the Child Care Flexibility Trials. There were a number of components to the trials; each designed to test different ways of delivering flexible child care. Different approaches were trialled within selected sites across Australia, and involved the government working with service providers and key stakeholders, including representatives of police, nurses and paramedics in selected jurisdictions of Australia. The focus of specific trials included:

- flexible care provided through family day care;

- extended hours of operation in long day care settings;

- weekend care in a centre-based setting; and

- school holiday care for older children and for children with special needs.

In addition, coordinated by a national outside school hours care provider, more than 60 action research projects were developed within outside school hours services, with the overall aim being to improve the skills and knowledge of educators, and to identify opportunities to create more flexible and responsive service provision for local communities.

The AIFS evaluation comprised analyses of parent, service provider and other stakeholder perspectives. This report draws upon the data collected from parents. Specifically, these data include:

- qualitative data, from interviews with a sample of police and nurses, and families at services participating in the Child Care Flexibility Trials; and

- survey data, collected through an online survey from a sample of families using selected outside school hours care services.

More information about these data sources is provided in Section 2. The focus of this report is not on the outcomes of the Child Care Flexibility Trials. However, we refer to the trials inasmuch as parents' experiences of specific trial projects provide new insights about the delivery of flexible child care. (For an overview of key findings from the evaluation of the Child Care Flexibility Trials, refer to Appendix A and Baxter and Hand (2016)). The interviews and survey data captured broader information about parents' use of and demand for flexible child care, and it is these data that are the focus of this report.

While not representative of all Australian families, research using these data permits us to begin answering the questions set out above, providing some evidence from which we can speculate on potential implications for all Australian families. Some analyses of nationally representative Australian data are also included to contextualise the findings.

The report contributes to the body of research that explores parents' decision-making about child care and employment. In particular, our focus on "flexible" child care is situated within a broader literature in which different characteristics or types of child care might be sought by different families. For example, Peyton, Jacobs, O'Brien, and Roy (2001) found that in seeking child care some parents prioritised finding high quality care, while others prioritised practical considerations such as location and hours. Some parents specifically sought centre-based care and others relative care. Johansen, Leibowitz, and Waite (1996) explored the qualities of care that parents favoured, showing that quality is not a unidimensional construct, with parents valuing such characteristics as the educational and developmental attributes of the care provider, the convenience of the care (e.g., location, cost and hours) and knowing the caregivers. Meyers and Jordan (2006) discussed how parent must make trade-offs among their preferred care qualities, in order to accommodate competing demands of earning and care giving. In fact, drawing upon the work of Emlen (see Emlen, 2010, discussed below) they further noted that "parents construct their understanding and tastes for ‘quality' itself within the context and constraints of their work, family and care alternatives" (p. 61).

Parents are diverse in the qualities of care that they seek, also seeking different characteristics of care for children at different ages (e.g., Boyd, Thorpe, & Tayler, 2010; Johansen et al., 1996; Rose & Elicker, 2008). Some parents may be more constrained in their care options than others. For example, the analyses of care characteristics sought by parents, by Peyton et al. (2001), revealed practical considerations tended to be valued over quality by families with lower incomes and mothers working full-time hours. In addition to income and work hours, other factors that can contribute to parents being more constrained in their child care options include the area of residence (with fewer options potentially in regional areas, especially if family do not live close by) and family size. Demographic factors such as these are typically found to also explain differences in the types of child care used (e.g., De Marco, Crouter, Vernon-Feagans, & The Family Life Project Key Investigators, 2009; Johansen et al., 1996; Tang, Coley, & Votruba-Drzal, 2012).

Our data do not allow us to fully explore financial aspects of the care and employment decision-making process, but we will touch on these issues as they emerge. Differences according to other demographic characteristics are also explored, particularly thinking about ages of children, family composition and location.

The availability and characteristics of care, or beliefs about care, may affect parents' (in particular mothers') employment decisions (Meyers & Jordan, 2006). This is most often recognised in relation to mothers withdrawing from employment because of child care constraints (e.g., cost or availability) or beliefs about appropriate forms of child care. An extensive body of research has examined how child care factors (in particular, cost) might affect mothers' employment decisions (see, e.g., Connelly & Kimmel, 2003; Leibowitz, Klerman, & Waite, 1992). In others, in recognition that decisions about employment and child care use are likely to be made together, parents' work and care characteristics have been modelled jointly (e.g., Connelly & Kimmel, 2003; Kalb & Lee, 2008; Kornstad & Thoresen, 2007; Leibowitz et al., 1992; Powell, 2002; Rammohan & Whelan, 2007). Parents' employment decisions are usually not just about whether or not to work, as they may make choices about employment characteristics, given child care constraints, opportunities or views, perhaps selecting jobs with fewer hours or with hours at certain times of day. This was illustrated by Pungello and Kurtz-Costes (1999), who gave the example of a new mother who might elect to reduce her work hours from full-time and little schedule control to work part-time after the birth of a child, given a preference to be at home part of the day with her child. This manipulation of parents' environment to align it more closely with parents' beliefs, then allows choices about child care to better align with those beliefs. This is relevant in thinking about parents who work non-standard hours, who in some cases may have selected those jobs or those hours because they have informal or family-based care available to them and that they prefer to use over formal types of child care. Pungello and Kurtz-Costes (1999) rightly noted, though, that not all parents are able to adjust their environments (work hours or other factors) to match their preferred or available care options.

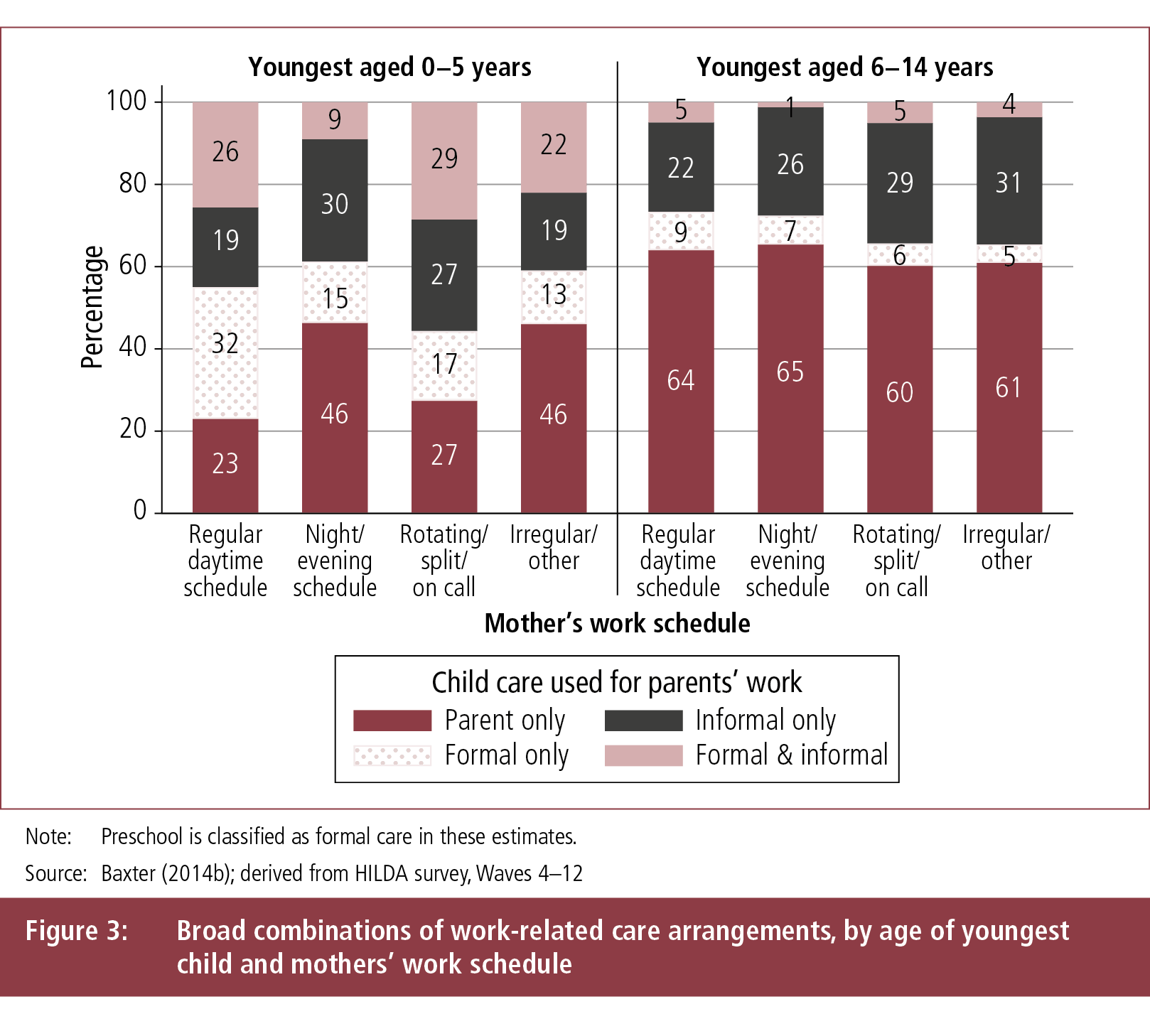

Much of the research on child care decision-making or use highlights the difficulties faced by parents who work non-standard hours. Some of this research explores child care decision-making or use within low-income families, given concerns that these families might be at greatest risk of having such jobs, yet have fewer resources to purchase high quality care at non-standard (or variable) hours (Henly & Lambert, 2005; Sandstrom & Chaudry, 2012). When parents work non-standard hours, families are less likely than other working families to use formal child care (Han, 2004; La Valle, Arthur, Millward, Scott, & Clayden, 2002; Moss, Hill, & Wilson, 2008; Riley & Glass, 2002). In particular, a greater reliance on family-based and informal care providers has been observed for these families. For example, Riley and Glass (2002) found that the care arrangements of 6 month olds were most strongly predicted by mothers' work shifts and work hours, with evening or night shift work by mothers associated with a higher likelihood of using familial care (specifically, a spouse, relative or friend) and longer work hours associated with a greater likelihood of using centre-based care or family day care homes. However, it is not clear to what extent parents' lesser reliance on formal care, in these circumstances, is a consequence of the lack of availability of such options, or a preference by parents (Meyers and Jordan, 2006). In Riley and Glass's (2002) study, parents often considered familial care to be their ideal care arrangement for these 6 month olds, and so a high proportion of families in which mothers worked non-standard hours had care arrangements that matched their ideal arrangement.

A particular problem in relation to child care is that some jobs (such as in the case of the nurses and police we spoke to) not only involve work at non-standard hours, this work also involves variable hours. Bihan and Martin (2004), in describing child care for parents working atypical hours in selected European countries, noted that while work at non-standard hours might be problematic, the care can nevertheless be planned and can therefore be relatively stable. But when work hours change, such planning is not possible, and "the care solution has to be reinvented, often informally, calling on a network of relatives or neighbours" (p. 567). Some parents with such flexible jobs will have some say over their work hours, such that they can attempt to fit their work around the availability of care, but others will not. Parents working flexible hours often have family-based solutions (i.e., sharing the care between parents in couple families), or rely on informal carers (Le Bihan & Martin, 2004). But it is also commonly reported that parents in these circumstances must rely on a mix of formal and informal arrangements, such that their care patterns are complicated, unstable and also unreliable.

Associations between parents' employment—specifically non-standard and variable work hours—and child care are complex, as highlighted in the discussion above. This research report contributes to the literature by providing an in-depth examination of parents' use of and needs for flexible child care in the context of different employment and family circumstances. The main contribution is the qualitative research undertaken using the interviews with parents, although this information is supplemented with the survey data from the school-aged care survey, and also with some national data about child care in Australian families. Qualitative data are particularly useful to help disentangle complexities as are evident in looking at work and care decision-making (Sandstrom & Chaudry, 2012). To present findings from this research, to fully represent parents' perspectives on flexible child care, we broadened our focus beyond child care decision-making, to capture how child care fits within other aspects of parents' lives. Emlen (2010) wrote about this, discussing how parents may seek flexibility from different places in order to better meet the demands placed upon them. He discussed flexibility as potentially existing within the workplace, the family or household, as well as within child care arrangements. The data collected through this research reflected this also, and so our presentation of parents' perspectives follows Emlen's framework, by presenting analyses in sections for "employment contexts", "child care" and "family contexts".

As Emlen (2010) articulated, when parents are lacking flexibility in one area, such as when they lack flexibility in their work hours, they will seek it elsewhere, through their family, child care or both. This is particularly relevant when thinking about the child care needs of parents who work non-standard hours. As will be described in this report using the new survey data, non-standard work hours can allow parents the flexibility to manage their child care needs, and such families are not necessarily seeking different child care arrangements. For others, especially those with little control over their working hours, managing child care is much more of a challenge, and for them, more flexible care might be useful if it could be responsive to their demands for care.

The findings from this research are structured as follows:

- Section 3 explores work contexts in relation to child care issues. As well as considering non-standard and varying work hours, we discuss how child care issues are intertwined with decisions about returning to work, the length of work hours or number of shifts. We discuss parents' difficulties in managing any extra requirements of their work, such as travel or overtime, and consider how associations between work and child care might vary with differences in the flexibility of working hours, and workplace policies and cultures.

- Section 4 focuses on child care, to describe how "flexible" child care fits within parents' demands for child care overall. Flexibility in child care is often considered from the perspective of whether care is available outside standard hours (such as early morning, evening, overnight and weekends) or can be changed or booked at short notice. However, we found that other qualities of child care can give parents some flexibility. Parents' demands for and use of flexible child care are discussed, highlighting the opportunities and challenges associated with different approaches taken.

- Section 5 then turns to family contexts, including how child care options vary according to child as well as family characteristics. In addition to child age, we present some findings related to the circumstances of children with special needs or when children are sick. We further discuss how work and child care options vary in single-parent families, families with little family support and families in regional areas.

- Section 6 synthesises the key learnings about what parents seek to better manage their work and family obligations, with a focus on thinking about flexible child care options.

- A final section concludes, referring the findings back to the key research questions, and drawing out additional key issues arising from this research.

2. Data collection and methodology

The data used here were captured through interviews and surveys that were designed to answer a range of information about parents’ use of or demand for flexible child care, in the context of other information about their family and employment arrangements. We gathered information from families who had directly engaged with Child Care Flexibility Trial projects, as well as those who had not, such that a diverse set of information about families’ needs for and use of flexible child care was captured.

The two main sources of data drawn upon throughout this report are the Flexible Child Care Study (FCCS) and the School-Aged Care Survey (SACS). Each of these components is described further below. All data collection was approved by the AIFS Ethics Committee, a Human Research Ethics Committee registered with the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

We also include some analyses of other Australian data, to contextualise the findings. The key data sources are described below.

2.1 The Flexible Child Care Study

The Flexible Child Care Study (FCCS) comprised 119 qualitative interviews with parents, with potential respondents identified in two ways. One way was through services that had some involvement in the trials. The other was through key stakeholder groups of the Child Care Flexibility Trials, that is, representatives of the police, nurses and paramedics. Each of the recruitment approaches is described below.

Recruitment via the trial sites resulted in a total of 50 parents taking part in interviews. Some of these parents (40) were approached by AIFS interviewers, having been identified by service providers or project managers as expressing interest in or taking part in one of the trial projects and being willing to take part in the research. Others (another 10) volunteered to take part when asked at the end of the School-Aged Care Survey (described below) if they were prepared to be interviewed further about child care.1

Parents from stakeholder families were invited by email and through staff newsletters to contact AIFS to talk about the ways in which they currently manage working and caring for their children, any barriers they have experienced in achieving their ideal work and care arrangements and ideas about child care options that they would like to have available to them. This recruitment resulted in a total of 69 interviews being undertaken. This included 12 nurses (all females), 56 police officers (29 female, 27 male) and one paramedic (male).

Data collection in the FCCS was done by telephone, with interviews conducted using a semi-structured approach. These interviews covered families’ use of and need for flexible care, and captured information about parents’ employment and family circumstances. Importantly, these interviews probed parents on how their existing care arrangements were working for them, in order to capture views of how different flexible child care solutions might, in their opinion, better meet their needs. For parents at trial sites, additional questions were asked concerning their engagement (or not) with the aspect of child care being trialled at that site. Once completed, the interviews with parents were then transcribed and analysed thematically to both draw out parents’ views around the key research questions as well as to explore any additional emerging themes.

Characteristics of the FCCS sample are shown in Table B1, Appendix B, disaggregating according to whether families were recruited through trial sites or through stakeholder organisations.

2.2 School-Aged Care Survey

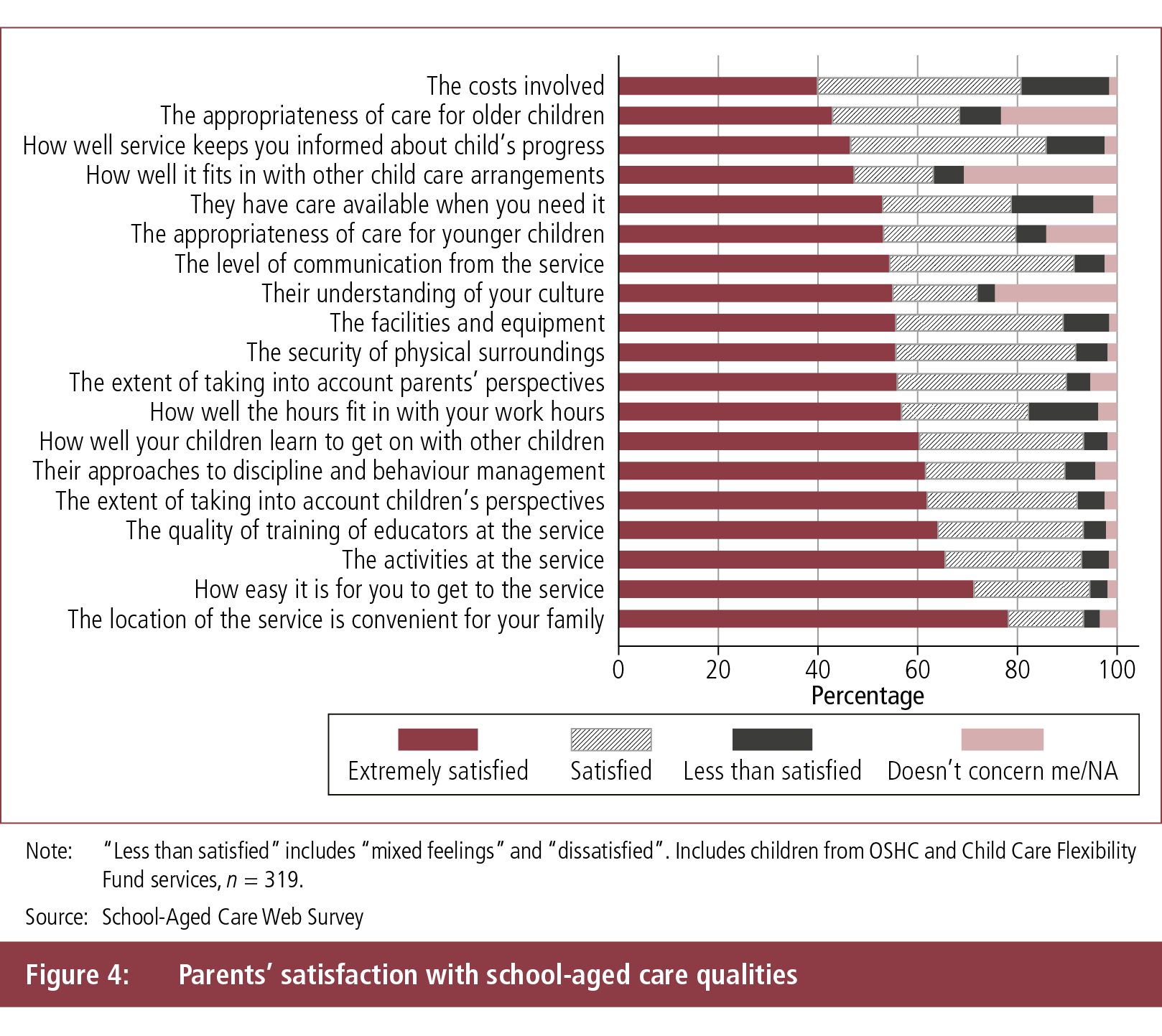

To provide insights on flexible child care use and needs among families with children in school-aged care services, an online survey was developed, referred to as the School-Aged Care Survey (SACS). This survey captured details of parental and family characteristics, child care patterns of all children in the family, and parental satisfaction with various aspects of their care arrangements. There was a focus on parents’ use of or need for different forms of flexible care, such as care outside of standard hours.

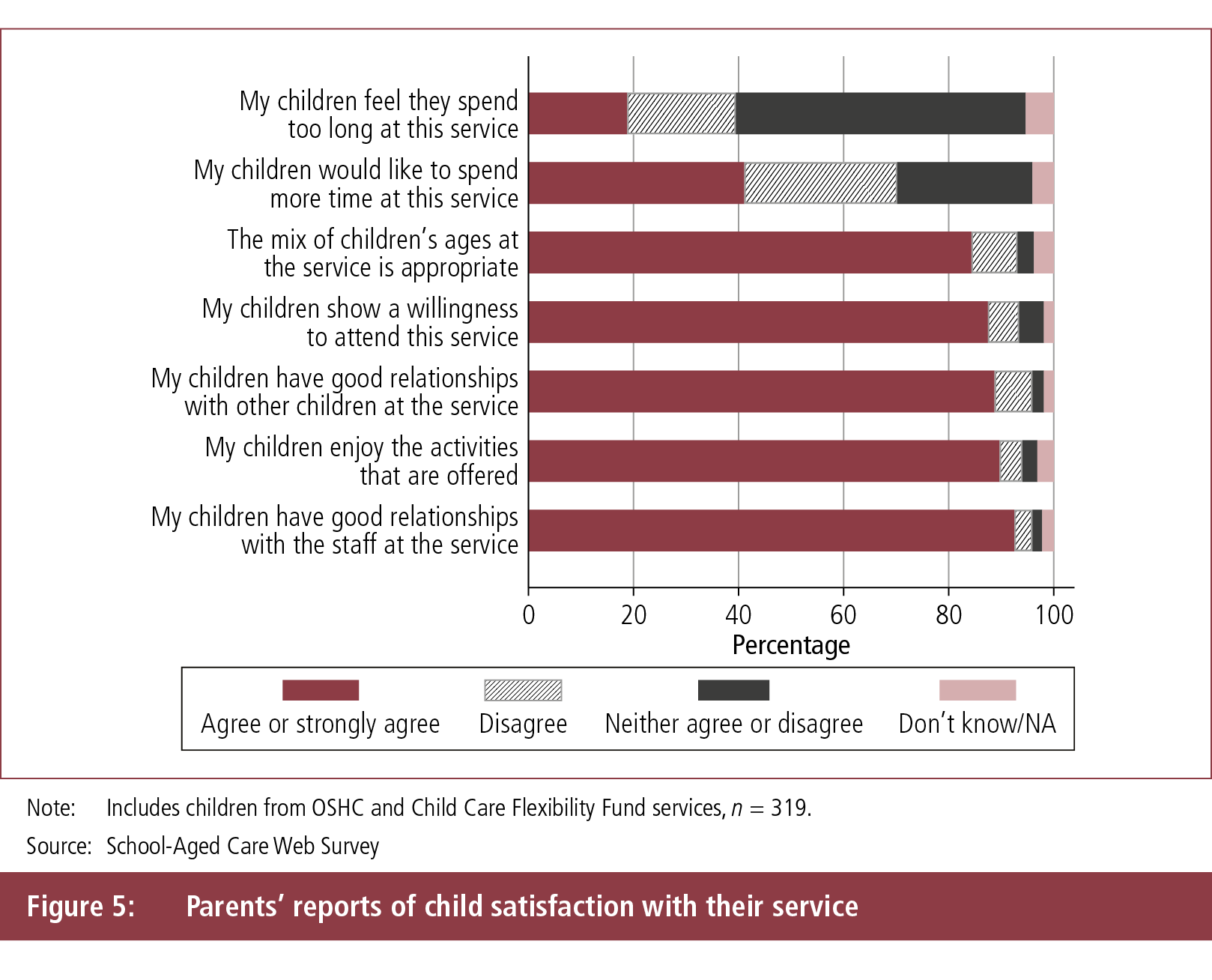

To recruit parents for this survey, all project officers of the school-aged care action research projects were asked to forward an invitation email to parents enrolled at their service (refer to Appendix A for more information). Overall, out of 38 projects that were expected to send invitations on to parents, we received complete responses from 260 parents in services attached to 17 of the projects. Further, parents at other school-aged care services involved in the trials were invited to participate in this survey, with a total of 59 parents completing surveys for these projects. This gave a total of 319 respondents.

The survey largely comprised fixed-choice survey questions, enabling us to calculate numbers and percentages responding in particular ways. This has been done throughout the report, where appropriate. None of the estimates from this survey are weighted, as it was impossible to identify the sampling frame, given we had no information about the families that received the invitations to participate in the survey. The survey also included some open-text questions, and we have used parents’ responses to these items to elaborate on some of the survey data, and to reinforce the findings emerging from the FCCS.

The characteristics of the sample are shown in Table B2. Note that this sample is not representative of Australian families with school-aged children, since it has been sourced only from families using child care for their children.

2.3 Other Australian data

To analyse child care patterns from a nationally representative survey of Australian children, we refer to data collected through the ABS Childhood Education and Care Survey. Data collected in 2011 have been presented here. These have been analysed, using the confidentialised unit record file, to show child care patterns by age and mothers’ employment status.

We also refer to some data collected in the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey, to explore child care use by mothers’ work schedule.2

Further, various ABS datasets are used in setting out characteristics of employment—they are referred to where presented in Section 3.

1 A total of 81 parents expressed willingness to participate in another interview. From these, we selected a sample of 20 respondents to undertake qualitative interviews. They were selected to cover a breadth of projects and families with varying needs or use of flexible child care, as identified from their responses to the web survey. We were able to schedule interviews with nine of these parents (plus one provided information to us by email).

2 The HILDA Project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported here are those of the authors and should not be attributed to either DSS or the Melbourne Institute.

3. Parents' perspectives on employment

3.1 Introduction

Parents’ work contexts, in conjunction with children’s ages, are key factors in explaining the child care needs of families. This section uses the qualitative and survey data to describe the links between parents’ work contexts and child care, by first looking at how parents’ decision-making about employment is related to their perceptions about or access to child care.

The importance of first considering employment contexts, in order to understand child care demands, was because we found that when parents were describing their employment arrangements they often referred to how these arrangements had been made in consideration of their child care needs and constraints (or beliefs). That is, families had often manipulated their work arrangements to fit with the child care they had available to them. These adjustments to work were often not insignificant changes, with some parents changing jobs or changing to part-time work in order to find a situation that meant their child care could be managed. As a result, families were not all in immediate need of different care arrangements. This, in part, is likely to have contributed to the lower than expected take up of the child care options trialled in the Child Care Flexibility Trials (see Appendix A).

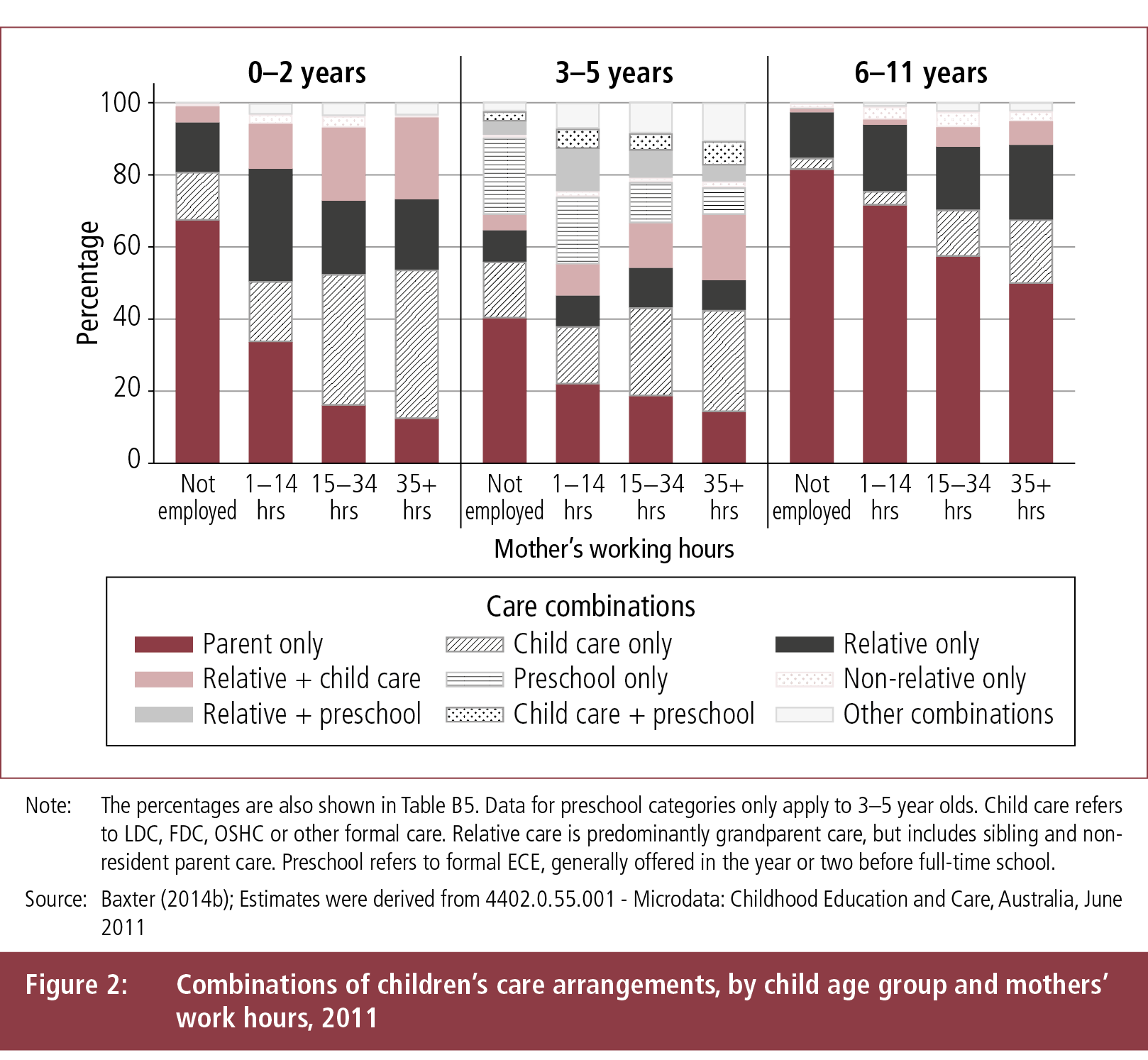

This section, therefore, explores how views about child care or child care opportunities and constraints contribute to the way parents construct and negotiate their employment situations. In particular, findings related to decision-making about mothers’ employment within the context of child care are presented. Decision-making about fathers’ employment is not explored to the same extent, as our findings are consistent with broader statistics for Australia that show it is mothers, and much less often fathers, who adjust their work hours when families have child care needs. Nevertheless, there was considerable evidence that fathers took advantage of their work conditions by varying shifts, using flexibility in start or finish times, or taking time off to participate in the care of children. So while we focus more on maternal employment, we also recognise the role of fathers and their workplaces in this discussion.

We start this section by examining how decisions about maternal employment are related to views about non-parental child care (subsection 3.2), and then how child care concerns factor into decisions about returning to work after a period of leave (subsection 3.3). The next subsections discuss how child care issues feed into parents’ options for particular aspects of work, including work hours (subsection 3.4), work at non-standard times (subsection 3.5), work that involves varying hours (subsection 3.6), work that offers employees flexibility in their hours (subsection 3.7), and other workplace or employment characteristics (subsection 3.8). A summary of this section follows in subsection 3.9.

3.2 Maternal employment decision-making

Feeding into the plans parents make about maternal employment and possible use of non-parental child care are parents’ own values about parental versus non-parental care of young children (Rose & Elicker, 2008). This includes mothers’ and fathers’ views about motherhood and gender roles within the home. Further, mothers, in particular, might be influenced by moral or social expectations regarding what is seen to be “good mothering” (Duncan & Edwards, 1999; Duncan, Edwards, Reynolds, & Alldred, 2003). The influence of these views will lead some parents to look for ways to care for children that minimises their use of non-parental care, regardless of the quality and flexibility of options available. In the context of the Child Care Flexibility Trials, it is important to note that some parents with particularly strong views about prioritising parental care of children will be more resistant than others to change their employment (or child care use) if it means taking up more non-parental child care, even if offered high quality, flexible care options.

Strong preferences for parental care may lead parents (especially mothers) to withdraw from or curtail employment such that non-parental care is avoided or at least minimised while children are young. This is most commonly seen in families in which mothers leave paid work for a time to care for children, taking a period of leave or other time off work.

In the FCCS, women often talked about taking time off work when children were born. Most had not taken a lengthy period of time off work, but had resumed work while their child was quite young. (The nature of our recruitment strategy may mean that we have not captured those who left work with the intention of prioritising parental care of children for a more extended time.)

We know from wider research that mothers’ engagement in paid work depends not only on views about parental (and non-parental) care of children, but also upon financial and non-financial rewards gained from employment, and opportunities to engage in employment that fits with available or preferred child care arrangements (e.g., Boyd, Walker, & Thorpe, 2013; Hand, 2007). Among employed mothers in the FCCS there were divergent feelings about paid work. Some mothers expressed their enjoyment of work, and so were prepared to deal with the complications of child care in order to keep working. For example:

I actually do enjoy my job and so I have to sacrifice something, and that sacrifice is trying to organise care for the children. And I only work part-time, so it’s not every day. (Mother, partnered, school-aged children only)

For others, work was viewed as a means of meeting financial needs, or just something they felt they had to do. For example:

I’m not interested in career progression or anything like that. I go to work to feed my kids. (Mother, partnered, under-school-aged child only)

Oh, totally, my ideal preference in the ideal world would be to be a stay-at-home mum till she at least started school. And still have her in [child care]—because I think child care plays a very essential role … because they learn very important skills there—but to be definitely a stay-at-home mum for the first few years. But I’m not in that ideal world. (Mother, partnered, under-school-aged child only)

Clearly, preferences and realities of parents do not always align, although parents in the FCCS were generally quite reconciled to the situation when this occurred. For example:

Yes, I think I’d like to just stay at home with the kids. You know, but I can’t, so that’s fine. But I’m quite happy with them doing two days. Like when [child 1] and [child 2] go to school, I’m still going to leave [child 3] in two days a week because it’s working quite well and he’s happy, so I’m happy. I don’t want to change their routine too much if I don’t have to. (Mother, partnered, under-school-aged children only)

Others in the FCCS talked about feelings of guilt and regretting missed time with their children. Such feelings were reconciled through awareness that children were happy and well cared for by their carers. For example, this mother, working full-time as a manager in retail, said:

It’s a big commitment working full-time. And it’s also the feeling of guilt that your child is in day care and you’re at work, and you always feel that little pang of guilt. But the reality is that we need the second income … You know, [child]’s happy. I mean in the end all I care about is that she’s happy. So it does work for me, it’s working OK at the moment … It works for me as long as she’s happy. (Mother, partnered, under-school-aged child only)

Another mother, who was unhappy with the quality of her child’s care, said:

The quality is crap but, like I say, right now I just really tried to come off like not even think about it literally, because I mean it’s just bad. I feel guilty all the time just thinking about it. (Mother, single parent, school-aged child only)

She was asked whether she would feel less guilty if she felt better about the quality, and she replied, “Of course it would, it would make me feel so much less guilty, definitely, make me feel like working even more, you know”.

The availability of high quality, flexible, child care options is likely to be of value in families such as this one. For example, those who were able to access more flexible care through the Child Care Flexibility Trials (particularly the family day care options) did report engaging more with work, or at least finding that they were better able to manage their work and care responsibilities, and that their wellbeing and their children’s wellbeing were improved as a result.

Because decision-making about work and child care will be affected by preferences, constraints and opportunities, decisions by mothers regarding their involvement in paid work will not always appear “rational” in the economic sense of this word. In particular, some families with higher child care costs perceive that they experience little financial gain from the mothers’ employment. For example, this single mother, who is a police officer, stated:

I’ve got friends that I can ask to look after her, people who are training in child care and things like that, to give them experience, but you’re paying them $20–25 an hour. And when you’re looking at 9 hours, you know, it’s not worth working. But I refuse to give up work so—not that work comes first—but I refuse to give up the independence of having that extra money that I need to. Well, it’s really hard. (Mother, single parent, under-school-aged child only)

The cost of child care was an issue for many families in the FCCS using formal care, although perceptions of affordability varied considerably, depending on what type of care was used, how much was used, and how much the actual costs were relative to income, after taking account of government assistance.

The cost of different care arrangements, in the context of family or maternal income, is likely to be part of the work and care decision-making package for many families, although some families are able to take a loss in income for a time. As cost is only one aspect of child care, in nationally representative surveys (such as the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia [HILDA] survey), when mothers are asked about reasons for not working or not using child care, cost is reported to be a main reason by a minority of parents. Views about parental care of children usually take precedence (Baxter, 2013a; Hand & Baxter, 2013; Nowak, Naude, & Thomas, 2013; see also Duncan & Edwards, 1999; Duncan et al., 2003).

When parents express that they are not working because they prefer to care for their children, in some sense they are expressing that they prefer parent-only care rather than non-parental care. Some parents will have made a conscious decision to avoid non-parental care, based on experience or perceptions of what this would mean for them and their children. The cost of care may be one of the factors considered, as well as difficulties in finding care that suits their expected work hours. Other parents see it as their role to provide this care, particularly while children are young. For these parents, the qualities or availability of non-parental care alternatives may not have been considered at all, as their focus has been on altering their work arrangements to allow children to be cared for entirely by them, or sometimes by their extended family members. (See the discussion and examples of parent-only care for families with employed mothers in Section 4.9.)

Mothers in the FCCS were generally employed and did not often talk about leaving work as an option. Some employed mothers who were experiencing child care difficulties, however, demonstrated how such difficulties can intersect with feelings about parental care and lead them to consider non-employment. For example, a single mother doing shift work as a police officer, who has a complex set of care arrangements, said:

It’s a nightmare. I have nearly quit work four times because obviously raising my daughter comes first over work. (Mother, single parent, under-school-aged child only)

One of the parents in the FCCS noted that his wife was about to leave work, as the costs of child care meant it was not worth her working.

In the SACS, 10% of responding mothers were not employed (22 mothers). The average age of the youngest child among these mothers was 6 years, with all having at least one school-aged child. These mothers were asked to indicate (from a list of reasons) their reasons for being not employed. The main selections were “cannot find a job with suitable hours” (10 mothers), “prefer to be at home with children” (9 mothers), “have problems with child care” (4 mothers) and “cannot find a job suitable to skills” (4 mothers). Of the four mothers who said that problems with child care contributed to their not working, two had problems finding child care for a child with a disability, one could not access the after-school-hours care needed, and one reported that there was no child care available for her 13 year old, who was no longer in primary school but was not old enough to look after themselves. While “prefer to care for children” tends to be the predominant reason given for mothers’ non-employment in nationally representative studies, the SACS was not representative of all families, given it was drawn from families already using school-aged care for at least one child. (See Baxter, 2013a and 2013c, for some research on not-employed mothers, including reasons for non-employment.)

The above discussion was included to show some of the factors that affect parents’ decision-making about employment, beyond those specifically related to the availability of flexible child care. For parents (mothers in particular) to engage more in paid work, the availability of child care is likely to be a requirement for some families. But this is one of a number of factors that contribute to parents’ employment outcomes, with others including parents’ views about non-parental care, the financial implications of working and using non-parental care, and the availability of suitable employment.

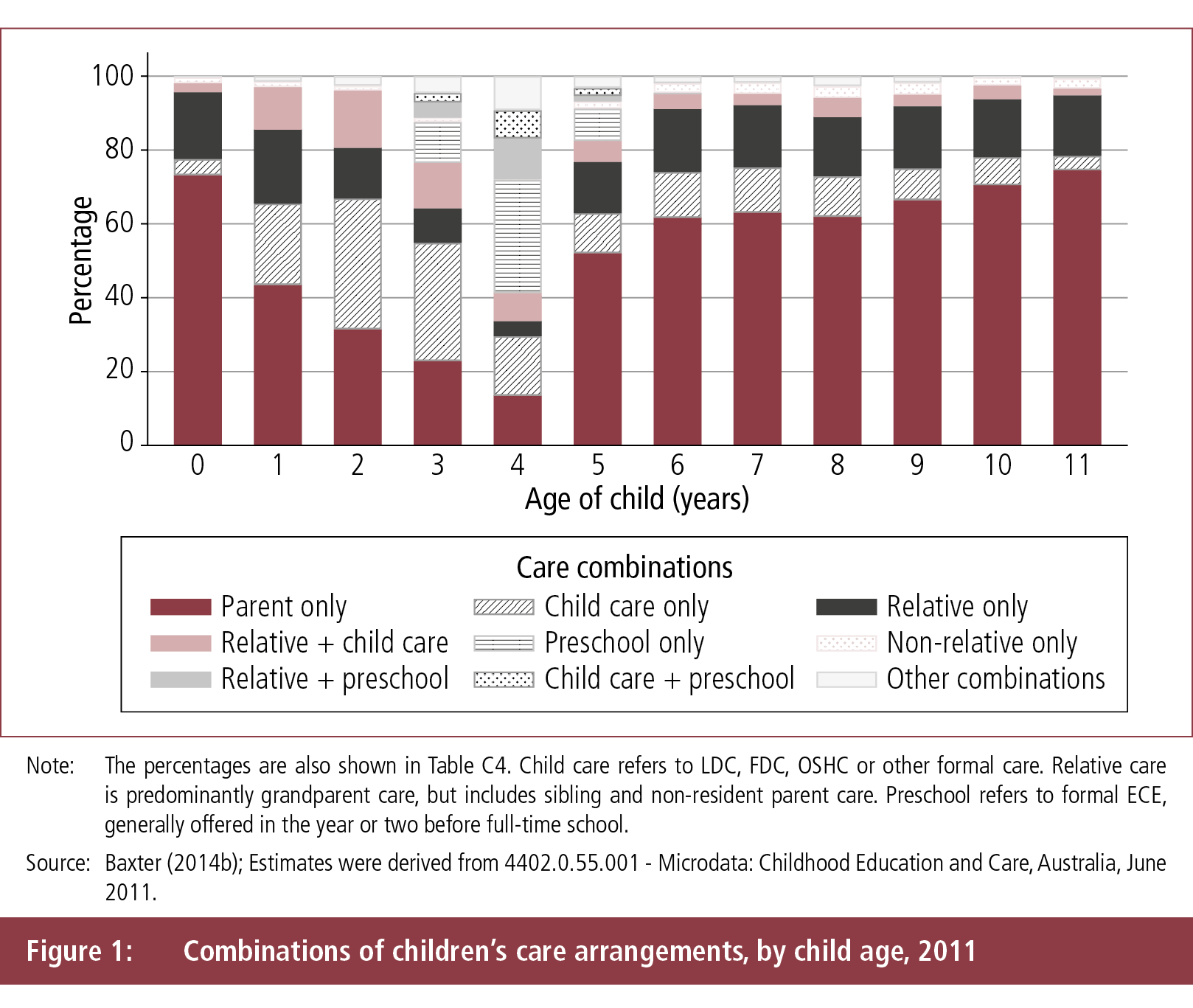

3.3 The practicalities of returning to work and child care

In many families, decisions about child care and employment are initially faced when contemplating a return to work after the birth of a first child. Australian data show that formal care is not always used at this time. For example, among children aged less than 1 year old in 2011, with a mother employed and back at work, 37% were cared for only by their parents, 49% were in some informal care, and 26% in some formal care (including 12% in both formal and informal care). For 1 year olds with an employed (and back-at-work) mother, 19% were cared for only by their parents, 51% were in some informal care, and 50% in some formal care (including 21% in both formal and informal care).3

Many of the FCCS participants expressed that if they returned to permanent or full-time work and the rotating shift, their child care needs would not easily be met by “standard” LDC or OSHC, given they needed access to care outside of standard hours or required care at varying times to match their shifts patterns. The child care solutions adopted by families are discussed in detail in Section 4. These solutions include sharing the care of children between partners, involving extended family members or friends and, for some families, making use of formal care arrangements.

Because of these expected difficulties, child care arrangements often had to be teamed with parents (usually mothers) changing work arrangements, and in subsection 3.4 we talk about part-time work in this context. In particular, the part-time working arrangement of some nurses and police officers in the FCCS allowed them to have shifts that complemented those of their partner, such that one parent was usually available to care for their child(ren). Such arrangements appeared to be time-limited, and parents talked about the stresses of having to come up with new child care solutions at the end of these periods.

For families who expected to rely on formal child care services upon mothers’ return to work, timing the availability of child care with a return to work can be quite difficult. This was illustrated in the FCCS by this mothers’ example of returning to work in an office job:

I suppose the main problem initially was trying to actually find a place, and trying to fit that in with return to work, because, you know, workplaces have certain requirements to notify them before you return to work. So it’s basically 8 weeks, but the day care centre would only provide 3 week’s notice of a place becoming available. So it sort of meant that you had to pay for day care for 5 weeks before returning to work, without having an income. So that was really quite difficult. And there’s also a bit of a shortage of places as well because I only wanted a part-time place. So trying to fit all that in with work as well, you know, with reaching an agreement for returning to work, was sort of really a bit difficult. (Mother, single parent, under-school-aged child only)

When asked whether this was just financially stressful, or were there other difficulties, she replied:

It was financial—as far as having to pay for the child care. But I suppose difficult because you don’t know whether there’s a place available. Like, it’s just really short notice and with the size of the waiting lists, you don’t even know if you’ll get offered a place that year or, you know, how long it’s going to take to even get offered a place. So there’s that sort of stress as well, with having no certainty of even having a place. (Mother, single parent, under-school-aged child only)

One male police officer in the FCCS told us of the difficulties he and his wife had in finding a child care place for their son. His wife was interested in returning to work part-time in retail, but their inability to secure a child care place after looking for 3–4 months meant this had not yet been possible:

No, we’re trying to get child care for the 20-month-old baby … We have our name down at a number of child care facilities at [city]. We’re on a waiting list and we’ve had no correspondence that there’s any vacancies … We’ve paid a fee at a number of places and got our name down on a waiting list to try and get child care. We just only want one or two days a weeks and we’ll be flexible—any day would suit, as long as we could possibly get one or two days. (Father, partnered, under-school-aged child only)

One of the FCCS respondents told us:

When I was pregnant with my child at 10 weeks, I enrolled my unborn child into five different child care centres. Once he was born and I needed to return to work, I was still unable to get him into any of those centres. So I ended up with a newborn in a bouncer under my work desk. (Mother, single parent, school-aged child only)

The nature of the FCCS and SACS samples meant we did not have a large representation of jobless mothers in either study. However, in each, as was apparent for families considering how to manage mothers’ return to work after a period of leave, we found that jobless mothers who were hoping to find work were clearly mindful of the fact that they needed to have or to find child care in order to take up work. For example, a jobless mother in the SACS had booked her child into a day of week of OSHC in preparation for her looking for work.

When families have child care in place for one or more children, they sometimes continue that arrangement even when events change and a parent becomes available to be at home for a period of time. This might occur if a mother takes leave after the birth of a new child, or if either parent loses their job. For example, a mother in the FCCS who had lost her job recently talked about why she did not take her child out of child care, even though this has been financially difficult for her:

Then you’re going to lose your place. So it’s like I’m hoping not to be out of work for too long. So why take him out for four weeks and then try to put him back and you can’t get it. So then what happens is I can’t go to work. So we’re better off keeping him there. It’s great for his social, you know, social aspect and also gives me the full day to actually look for work. (Mother, single parent, school-aged and under-school-aged children)

The above quote and some of the reports of other parents in the FCCS indicated that retaining a place in child care ensures there is a place when it is needed later, gives parents a bit more time for job search activities or being with a newborn, and can be beneficial when children are gaining from that care.

National child care figures likewise show children are often in some child care even when mothers are not employed, and this is especially so when children are at the ages when early childhood education (ECE) is generally seen to be beneficial. (See subsection 4.1).

The practicalities of returning to work and child care issues were most apparent in this research in families who had engaged with (or considered engaging with) FDC through the trials. Some families indicated that they were made aware of FDC as a result of the trials, providing them with an additional option that they may not have otherwise considered.

3.4 Work hours

While some mothers respond to concerns about non-parental care of children and a preference to prioritise parental care by withdrawing from work altogether, others are able to schedule their paid work in a way that allows them time for their children. Some mothers return to work gradually, perhaps starting with shorter hours to maintain greater time caring for young children and to accommodate breastfeeding, or perhaps because of limitations in the availability of child care. For example, from the FCCS, this nurse’s gradual return to work involved set hours and shifts, which meant she could initially use extended family to care for their child:

[My partner’s] parents live here, so up until she was 18 months old—I didn’t go back to work until she was 12 months old and then I went back at reduced hours and I only worked nightshifts and evening shifts so that she was only needing to go to the grandparents for a couple of hours here and there. So … I would drop her off on my way to the late shift and [my partner] would pick her up on his way home so she was only there normally for about 3 hours with them. (Mother, partnered, school-aged child only)

This mother seemed to view this arrangement positively, as it minimised the time their child was in some non-parental care. In contrast, another nurse in the FCCS had been somewhat constrained by the lack of availability in child care, although was also able to rely on her child’s grandparents to share the care. She hoped to increase her child’s time in child care and therefore her work hours in the future:

My husband’s parents live in the same suburb as us so they don’t live too far away. So my son goes to day care one day a week on a Friday because that’s all we can get him in for at the moment (the places are very limited), and she looks after him the other two shifts I’m at work … I think next year there’ll be a place available so he can go two days a week to day care, and then I will pick up an extra shift a week as well, because my mother-in-law wants to have him for the [other] two days, which is good. (Mother, partnered, school-aged and under-school-aged children)

Just as perceptions of child care quality can affect mothers’ decisions and feelings about returning to work (discussed in subsection 3.2), they can affect decisions about work hours. This mother, with a child in school-aged care that she rated very highly in terms of quality, said:

I have no guilt or emotional issues about leaving my child at before- and after-school care, because I know that in some cases the educational outcomes that he’s achieving there are perhaps more varied and extensive than what he would be receiving at home. So I’m more than happy and, yes, it has, I suppose, encouraged me to return to the workplace in a full-time capacity. (Mother, partnered, school-aged child only)

Mothers’ work hours may be constrained by the inability to find child care for non-standard work hours or for longer hours at work. Conversely, access to child care that supports this work may enable mothers (or fathers) to work longer hours. Respondents in the FCCS who had accessed FDC through the trials talked about how this allowed them to take up the shifts they wanted to do or to increase their involvement in paid work. For example:

Well, with the flexible child care, the extended hours and so forth, it allows me to work full-time, instead of part-time. So it allows me the best of both worlds. I can work full-time, which means more money coming in. And the flexible day care means that, you know, I don’t have to worry about what shift I do. (Mother, partnered, under-school-aged child only)

When asked whether FDC, accessed through the trials, had helped, this single mother says:

Of course, I mean if I didn’t come from a day care, then I wouldn’t be doing the afternoon shifts at all. And then probably I will be, you know, in a position where I have to either quit my job, because I can’t work enough, you see. So having the family day care has been a big help because he doesn’t go there every day, but on days that I have to work, he goes there, so that’s helping to maintain that balance between work and home, looking after him. (Mother, single parent, school-aged child only)

Mothers may also be constrained in their work hours because they have a reluctance for children to be in child care for longer than necessary. This might be especially so if child care is not judged to be a high quality substitute for parental care. Where parents feel they have access to high quality care, they are likely to report that their children are happy, and to report satisfaction with their work and care balance. (See discussion in subsection 4.3, as well as the analyses following.)

Among the FCCS families who had successfully been matched to an FDC educator as part of the trials, this meant a positive change in relation to work–family balance. This seemed to be most keenly felt by those who had changed to FDC from arrangements that had previously not been working well. For parents, the two main positive effects were in relation to parents’ engagement in paid work and management of their work–family responsibilities and associated stresses. Those new to child care also appreciated how well their arrangements were working.

It is quite common for mothers in Australia to work part-time hours upon return to work. Baxter (2013d), using 2011 Australian Bureau of Statistics Census data, reported that of mothers with a child aged under 1 year old, 6% worked full-time hours and 16% worked part-time hours, with the rest being on leave or otherwise not employed. For mothers with a 1 year old, 14% were employed full-time hours and 36% employed part-time hours. As children grow older, mothers are more likely to work full-time hours, although part-time work remains very common such that among all mothers with a child aged less than 18 years old, 36% worked part-time hours and 25% full-time hours. Among employed mothers who were at work (i.e., not on leave), 59% worked part-time hours and 41% full-time.

Among female respondents in the SACS, 46% of employed mothers worked part-time and 54% full-time. The higher rate of full-time work in this survey reflects that this sample was drawn from those using OSHC services, and families with full-time working mothers more often use these services than do families of part-time employed or not-employed mothers (Hand & Baxter, 2013).

About one-quarter of the mothers in the SACS working part-time hours preferred to work more hours. Most commonly, mothers said they were not working more hours because they could not get extra hours in their present job or they could not manage both extra hours of work and their other responsibilities. Some mothers said they were not working their ideal hours because they could not find another job with the hours they wanted, or they had problems with child care. Looking specifically at the child care reasons given, one female respondent in the SACS, who worked casually on weekends, said she would like to work more hours but had problems with the availability of care for two children, and also had problems with the costs of care:

Coordinating getting the same days of long day care for the youngest two and OSHC for the eldest. Cost of child care makes it not worth working except on weekends, when my husband looks after the children. (Mother, single parent, school-aged and under-school-aged children)

One other parent who responded to the SACS mentioned costs as a child care problem. Another preferred their child was not in any more child care than currently used, and another reported their children didn’t enjoy after-school care, so they had them attend only one day per week. Two parents reported having difficulties with child care for children with special needs:

My child with a disability is unable to attend an after-school program for children with an intellectual disability until he is 12 years of age, due to the current funding criteria. (Mother, partnered, school-aged and under-school-aged children)

My 10-year-old child is not eligible for after-school care. (Mother, partnered, school-aged children only)

Another two had difficulties managing their care arrangements along with work, such that their work options were constrained:

Expensive long day care for infant, with pick-up and drop-off times between school hours, leaves 4 hours’ daytime work available. Also, other parent works full-time. (Mother, partnered, school-aged and under-school-aged children)

Daughter in long preschool care, which isn’t late enough for a normal 9–5 job. (Mother, partnered, school-aged children only)

From the FCCS, this was similar to the experience of a nurse who reduced her work hours because their family wasn’t managing when she worked longer hours. As she noted, she would actually prefer to work longer hours:

I would like to go back to the four shifts I was doing. I was doing four shifts a fortnight and I had to drop down to three because we couldn’t juggle. (Mother, partnered, under-school-aged children only)

In the FCCS we also heard from some mothers who had returned to work full-time because part-time work was not available to them in their job or if they wanted to continue their career. For example, this mother returned to full-time work when her daughter was 6 months old:

If I wanted this position—which I did, because I wanted to continue my career—then I needed to be there on a full-time basis. I made the decision to go back full-time. (Mother, partnered, under-school-aged child only)

Part-time work was common in the FCCS, with a majority of female respondents (and partners of male respondents) being employed part-time. Many referred to a “part-time work arrangement” that allowed them to work shifts that complemented their husband’s. As many shift-working parents referred to significant problems in being able to access suitable child care for their changeable shift patterns, working complementary shifts in this way was the only way they were able to sustain employment (see subsection 5.8).

For some families in the FCCS, especially those with younger children, reduced hours meant children could be in non-parental care for less time, and this was a key reason for their working shorter hours. For example:

We want to be her primary caregivers, so I don’t want her in day care any more than 2 days a week, really. We change our life around that. We had her so we would look after her, not let someone raise her for us, so it’s only really to cover the times that we have to, you know, work … Like, we just don’t want other people to raise her. We’d rather raise her. (Mother, partnered, under-school-aged child only)

This family also had an added complication that their daughter was picking up a lot of illnesses through participation in day care, and they were concerned that she would be sick all of the time if she was in child care for more days per week.

There were no instances in the FCCS of fathers working part-time hours to minimise non-parental care. There was a family, though, in which the husband had previously been unable to get full-time work because child care was not available, and his work hours had to be limited to those hours his wife was home. This family gained access to FDC through the trials, and this involvement meant he could increase his hours to full-time. Further, the mother could engage more easily with work, staying late to finish her work if needed, and more easily manage her on-call shifts. This was viewed very positively within their family.

Through the FCCS fathers were often portrayed (by themselves or their spouse) as active participants in child care, taking turns to care for children according to each parents’ work schedules. For example, one mother, a customs officer, referred to her husband’s use of his shifts (as a full-time police officer) to take part in their child’s care:

When I was working, he tried to work the day off around my shifts so he could maybe mind our daughter. (Mother, partnered, under-school-aged children only)

The recognition of the importance and value of father-provided care is consistent with research on “ideal” care providers, which reveals that fathers are often considered to be the best option for child care when mothers are not available (Riley & Glass, 2002).

With part-time work often seen to be helpful to parents in managing their child care arrangements, it is not surprising that among families with parents working full-time hours, we also heard in the FCCS and the SACS of some of the difficulties faced when working long hours. In particular, long work hours were difficult if they involved an early start and/or a late finish, for which child care options might be limited. (See subsection 3.5 on working at particular times of day.)

The stress and difficulties associated with managing child care in a family in which the mother works long hours is evident in the following quote from the SACS. This is in response to the question that asked whether there was anything particular about her employment that made managing child care difficult or easy. She referred to the difficult aspects:

The times when I need to make teleconference calls: 6–7 am in the morning or late evenings, 11 pm. Also, travelling to drop my son off in the mornings at my mum’s (three times a week) makes me leave home really early so I can get to work on time. It’s not fair on the kids as they get home late, and by the time we do dinner/homework/bath then to bed, they don’t get to go to sleep till 8–8.30 pm, and they need to be up at 6–6.30 am. [There’s] too much pressure on families. We don’t get to enjoy each other. Everything is a rush and we become robots as we seem to always fight against time. On the weekend we need to do the household activities and get ready for another week, so it makes it hard to arrange any family activities, and kids need our attention and love. We just seem to be in routine and so focus is getting the jobs done, [and] we don’t have enough time for each other. (Mother, partnered, school-aged and under-school-aged children)

While work hours are typically measured on a weekly basis, and comparisons made between full-time and part-time workers, the FCCS revealed that an important dimension in terms of child care was the length of a single shift. A number of the respondents in the FCCS worked rotating 12-hour shifts. Others worked rotating 10- or 8-hour shifts. The duration of shifts vary with occupation and workplace, but with little flexibility in being able to work other than the shift designated.

Finding appropriate child care that covers a 12-hour shift, plus time to get to and from work, proved impossible for a number of FCCS respondents, especially since those shifts were not fixed from one week to the next, and started and/or finished outside the operating hours of child care centres (see also subsection 5.5).

One nurse, an FCCS participant, talked about how the hours of the child care centre she used for her younger son would not work if she still had a job with 12-hour shifts. She had changed to a job with set 8-hours shifts:

It’s a longer day [facility], but it’s still only open from 6.30 till 6.30. So … like it’s still not suitable for the 12-hour shift, but because I’m doing the [other] job, it’s for five 8-hour set days a fortnight. So I can book him in for set days now. (Mother, partnered, school-aged and under-school-aged children)

Another mother in the FCCS, a police officer, had a part-time work arrangement to work shifts that complemented her husband’s full-time police work. Neither of their children were in any child care. As the shifts were 12 hours in duration, she had not been able to fit more shifts into her week with this arrangement:

I would like, financially, at this stage if I could work more, because we are really struggling financially. But I can’t pick up any more shifts because I struggle to get my 12-hour shifts in around my husband, let alone any more, and it would just completely take out any time that we have as a family. (Mother, partnered, under-school-aged child only)

Along with the duration of shifts, the times at which each shift starts and finishes varies across different workplaces, as discovered by this police officer who transferred to a regional police station:

This is the first station I’ve ever had that does a six till two and not seven till three. So that was another thing that I wasn’t aware of, and once a transfer’s through, you can’t pull out of it. So that poses its own problems. If it was a seven till three shift at that station, then day or child care centres can accommodate that. (Mother, single parent, under-school-aged child only)

However, she also realised that regardless of the hours of the day shift, the nature of a rotating roster meant there were going to be challenges anyway:

But then you’re not going to get an agreement where work’s going to give me all day shifts. That’s not fair on everybody else who works there. Because they’re going to want me to do afternoons and things like that. So then your day care centre shuts at six; you’ve got four and a half hours you’ve got to find someone. (Mother, single parent, under-school-aged child only)

3.5 Non-standard work hours

A key factor relating to possible demand for flexible child care is the degree to which workers’ jobs involve non-standard hours of employment. Here, we consider non-standard hours to involve work in the early morning, evening, overnight or on weekends, and explore how these work hours might cause challenges for families in how they manage child care. (We discuss how they manage child care in Section 4.) Some nationally representative data on women’s employment has been presented here along with findings from the FCCS and SACS, to provide some context to this research. We have not provided similar data for men or fathers, but of course their employment arrangements are likely to also matter to the way in which parents are able to organise the sharing of children’s care.

According to the 2012 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Working Time Arrangements survey, 6% of female employees usually worked the majority of their working hours between 7 pm and 7 am in all jobs.4 In the 2006 Working Time Arrangements survey, the information provided was slightly different, reporting on the percentage who usually worked any hours between 7 pm and 7 am, and this figure was 25% for female employees who held a single job.5

To explore this in more detail, we used data from the 2006 ABS Time Use Survey.6 Looking at weekdays on which women reported doing some employment, Table 1 shows the percentage in employment at some time during standard hours (between 7 am and 7 pm) and non-standard hours (between 7 pm and midnight and/or between midnight and 7 am), and also according to the location of the work (at home or away from home). As work across one day can span multiple locations and times, women could be classified as working in one or more of these time slots, and one or both of the locations.

| Standard hours | Non-standard hours | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 am to 7 pm | 7 pm to midnight | Midnight to 7 am | Either (7 pm to 7 am) | |

Note: Does not include work-related commuting. | ||||

| Home | 15% | 8% | 1% | 9% |

| Elsewhere | 91% | 11% | 8% | 17% |

| Total | 99% | 19% | 9% | 26% |

Overall, for women aged 25–54 years, 26% of weekday work involved some work during non-standard hours, with 19% of weekdays including work between 7 pm and midnight and 9% between midnight and 7 am. Most of those working in the morning did so away from home, while evening work was quite often done at home.

With respect to who was doing this non-standard work, the percentage of mothers working non-standard hours (23%) was just less than the percentage for all women aged 25–54 years. Partnered mothers were a little more likely than single mothers to work non-standard hours (24% compared to 21%). Mothers with children aged under 5 years were more likely to work non-standard hours (31%) compared to those with children aged 5–11 years (19%).

Among women aged 25–54 years who worked on weekdays, differences by occupation reveal that non-standard work was more likely for those employed as machinery operators or labourers (52% worked some non-standard hours on weekdays), and community and personal service workers (35%). It was least likely for clerical and administrative service workers (14%). See Table C1 for these occupational data, and the same data by broad industry groups.

For many of the FCCS police and nurse respondents, working shifts was something they were familiar with, with shifts commonly covering early mornings, afternoons, evenings, nights and weekends. Clearly, these shifts required parents to find solutions to their child care needs. Some parents intentionally sought out certain shifts that could more easily be managed. Some avoided certain shifts that were incompatible with their care arrangements, or incompatible with their views about family time and what was best for children’s wellbeing.

This quote, from a shift-working nurse in the FCCS, illustrates how shift work can sometimes be good, sometimes difficult, with respect to the times of day it allowed her to be there for her children:

Shift work has its bad points, working all over the place, but then it’s good too, you know—on an afternoon shift, when I’m still home to drop [child 1] off at school in the morning and have a play with [child 2] in the morning before I go to work in the afternoon. But then I’m not home for bedtime and dinnertime and all that sort of thing either. (Mother, partnered, school-aged and under-school-aged children)

Looking at parents’ references to working at specific times of day, evenings were seen by some parents in the FCCS as being a time that children should be with their parents. One nurse, a single mother, noted she did not work evenings because she did not have child care, but then, when asked whether she would think about evening work, said:

I wouldn’t entertain it because I’ve got him on my own, and I just feel I need to be there for my son and doing his homework. (Mother, single, school-aged child only)

She went on to say it would take a lot of trust, having someone else look after her child at night.

Another nurse, working part-time hours and generally working morning shifts, when asked if she would consider doing afternoon or evening shifts, said:

I’m happy not doing them because I don’t want her in care over dinnertime, bedtime … I don’t want her to be out of bed at 8.00–8.30 at night and then pick her up and have to bring her home and put her to bed … I guess it works for our family routine really. (Mother, partnered, under-school-aged child only)

Early morning shifts (or early starts in non-shift work) appeared to be difficult for some families, requiring juggling between partners or with another informal care provider (such as a grandparent) prior to the opening of child care centres or school. For example, this partnered nurse in the FCCS with one school-aged child and one younger child said:

But the biggest problem I find is that when I’m on a morning shift at work I start at 6.30 in the morning and the day care doesn’t open till 6.30 in the morning. So I either have to wake the kids up earlier to drop them off at my mother-in-law’s and she then takes them to day care and school, or they need to stay over at her house the night before. (Mother, partnered, school-aged and under-school-aged children)

Her husband also started work at 6 am so was generally not available to take the children to day care. Reliance on partners and extended family members in this way for morning shifts was quite common among FCCS respondents.