Working Together to Care for Kids: Foster and relative/kinship carers and their experiences

1 of 5

May 2018

Download Research snapshot

Overview

A significant number of children aged 0-17 years are in out-of-home care (the vast majority in either foster care or relative/kinship care).1 The foster and relative/kinship carers fulfil an important caring role for these vulnerable children. This Research Snapshot focuses on the socio-demographic characteristics of foster and relative/kinship carers and aspects of their care experience based on a survey of foster and relative/kinship carers.2

Key messages

-

Most of the carers interviewed were female, aged over 50, with significant numbers aged 65 years and older (15%). Relative kinship carers were older than foster carers.

-

Compared with the data of HILDA3 (representing general Australian households), carers' gross household income levels were lower and carers were more likely to be in public housing. Relative/kinships carers were less well off compared with foster carers.

-

Carers typically reported that they were approached by their jurisdictional department or agency to look after the study child.

-

The median duration of time that study children stayed with carers was 3.4 years, with just under one-half being with the carers for up to two years, and nearly one-tenth at least 10 years.

-

The vast majority of carers (86%) reported being aware that the study child had experienced at least one indicator of abuse, neglect or problems at home.

-

Over one-third of carers reported that the study child had at least one type of developmental conditions (i.e., an intellectual or physical disability, diagnosed behavioural problem, or diagnosed mental health condition).

-

A substantial minority of carers learnt of the study child's experience of abuse, neglect or problems at home, or developmental conditions after the child came into their care.

1 According to the data published by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare in 2017, 46,448 children were in out-of-home care at 30 June 2016 (with 55,614 children experiencing this sort of care during 2015-16).

2 The information in this Research Snapshot is based on Working Together to Care for Kids: A Survey of Foster and Relative/Kinship Carers, which collected data from 2,203 foster and relative/kinship carers in 2016 via telephone interview. The Working Together to Care for Kids Survey was conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) in 2016, in collaboration with the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS), and funded by DSS. The sample was drawn from foster and relative/kinship carers who registered in the states/territories (except Northern Territory) as formal carers of out-of-home-care children aged 0-17 years old at 31 December 2015.

3 HILDA refers to the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey. The HILDA project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research. The findings and views based on these data are those of the authors and should not be attributed to either DSS or the Melbourne Institute. To assess how carers' household income levels compared with those of general Australian households, the data of the HILDA survey collected in 2014 was analysed.

The carers

- The majority of carers in the study were females (88%) and older. On average, carers were aged 53 years, with only 12% aged under 40 years old and 15% aged 65 years and older. Relative kinship carers were older than foster carers. Nearly one-fifth of relative/kinship carers were 65 years and older, compared with one-tenth of foster carers.

- For relative/kinship carers, two-thirds (66%) were grandparents/great-grandparents to the child in their care; a further 27% were uncles or aunts, and the remaining 7% were other relatives (e.g., cousins or siblings).

- Twelve per cent of carers were Indigenous, higher than the national level of Indigenous population (3%), according to the 2011 Census (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013). This reflects the high percentage of Indigenous children in out-of-home care.

Carers' economic circumstances

- The majority of carers under 65 years old (55%) were not in paid employment, a quarter (25%) were in part-time employment and 19% were employed full-time.

- Results suggest that carers had a lower household income compared with Australian households overall (taken from HILDA 2014).4 For annual gross household income, one-fifth of carers indicated an income less than $30,000 per annum, one-third had $30,000-$59,000, and one-fifth reported an income of at least $100,000.

- Almost two-thirds of carers (64%) indicated that they either owned or were paying off their home, while 23% were renting and around one-tenth were in public housing. The proportion of carers in public housing was higher than for general Australian households (11% vs 4%).

- Relative/kinship carers were on average less well off than foster carers. Relative/kinship carers were more likely to have an income under $30,000 (28% vs 16%), to be renting (26% vs 20%), and to be in public housing (15% vs 5%) than foster carers.

4 To assess how carers' household income levels compared with those of general Australian households, the data of the HILDA survey collected in 2014 was analysed.

Carers' experiences

Becoming a carer of children in out-of-home care

- Almost two-thirds (64%) of carers, when asked about how the study child came into their care, indicated that they were approached by their jurisdictional department or agency, while a further 29% said they offered to care for the child. Over one-tenth (12%) reported that they were asked by the child's parents or family members to look after the child. A very small proportion said that the study child transitioned from a temporary care arrangement to a long-term arrangement in their care.

- Just under one-half (45%) of carers had one child in their care, 27% were caring for two children, and 22% had three or more children in their care.

Period of time looking after study child

- The median duration of time that study children had been looked after by carers was 3.4 years. One-third of carers (31%) reported the study child's stay to be between one and two years; 14% that the study child had stayed less than one year; and 13% that the study child had been living with them for at least 10 years.

- Relative/kinship carers reported longer care durations compared to foster carers.

The children in care

- The mean age of study children in foster or relative/kinship care was 9 years old, with the most common age ranges for study children being 5-11 years (44%) and under 5 years (23%). Fifty-two per cent were male and 48% were female.

- Just under one-third (31%) of study children were identified as Indigenous (i.e., as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander).

Child's prior experience of abuse, neglect and problems at home

Carers reported on study children's prior history before coming into their care, with the following six indicators: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, family violence in the household, and household member(s) with alcohol or drug use problems.

- According to carers' reports, 86% of the children in care had experienced at least one indicator of abuse/neglect and problems at home, and three-quarters had experienced one of the three forms of abuse (physical, emotional, sexual) or neglect.

- Carers most commonly reported that there was a household member(s) with alcohol or drug use problems (72%), followed by neglect (68%) and family violence in the child's own home (62%).

- One-half of the children in care had experienced emotional abuse before they came to the carers' households, with over one-third having experienced physical abuse, and one-tenth sexual abuse.

Carers were also asked about when they became aware of the abuse, neglect or problems at home the study child had experienced before coming into their care - whether they found out before the study child's arrival, on their arrival, or after their arrival.

Carers' responses are shown in Figure 1. As would be expected, relative/kinship carers were more likely than foster carers to indicate that they were aware of the abuse, neglect or problems at home prior to the child's arrival. This applied to all the indicators except sexual abuse (results are not shown in the figure).

Figure 1: When carers became aware of abuse, neglect or problems at home that study children had previously experienced

Note: Percentages are based on weighted data.

Child's developmental conditions before current placement

Carers were asked whether the study child had any of the following developmental conditions when he/she came to live with them: an intellectual disability; a physical disability; a diagnosed behavioural problem (e.g., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorders); or a diagnosed mental health condition (e.g., depression, anxiety).

- Over one-third of carers reported that the study child had at least one type of developmental condition. Eighteen per cent of carers reported that their study child had an intellectual disability and 15% a physical disability, while diagnosed behavioural problems and mental health conditions were each reported by 12% of carers.

- Overall a higher proportion of foster carers than relative/kinship carers reported that the study child had at least one type of developmental condition (38% vs 32%).

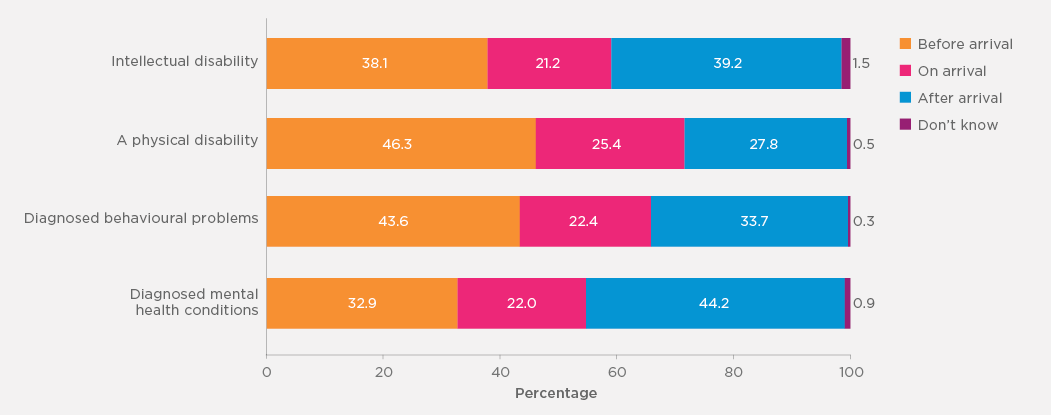

Figure 2 shows when carers became aware of the study child's developmental conditions. The overall patterns in the timing of carers' awareness of study children's developmental conditions were similar between the two groups of carers (results are not shown in the figure). Nevertheless, relative/kinship carers were more likely than foster carers to be aware of the child's developmental conditions, with the exception of diagnosed mental health conditions, before the child's arrival, especially the child's intellectual disability.

Carers were asked a number of questions about whether they believed they were provided with adequate information about the study child's history (regarding aspects such as his/her family environment, medical conditions, or any other information about the child that would have been helpful to know) prior to his/her coming into their care. A substantial minority of carers learnt of the study child's experience of abuse, neglect or problems at home, or developmental conditions after the child came into their care. It is not surprising then that one-third of carers felt that they were not provided with adequate information before the study child came into their care.

Figure 2: Carers who knew study children's developmental conditions, when they became aware of the conditions

Note: Percentages are based on weighted data.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2013). Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2011 (Catalogue No. 3239.0.55.001). Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2017). Child protection Australia: 2015-16 (Child Welfare series no. 66. Cat. No. CWS 60). Canberra: AIHW.

© istockphoto/Zukovic

Qu, L., Lahausse, J., & Carson, R. (2018). Working Together to Care for Kids: A survey of foster and relative/kinship carers. (Research Report). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Download Research snapshot

Related publications

Working Together to Care for Kids: Carer service use and…

This Research Snapshot focuses on carers' reports on their access to and views on service support.

Read more

Working Together to Care for Kids: Carer support and…

This Research Snapshot focuses on carers' reports on training they had received and the degree of contact with their…

Read more

Working Together to Care for Kids: Carers' views - Rewards…

This Research Snapshot explores the thoughts and feelings of carers of out-of-home-care children about their care…

Read more