Child Care Package Evaluation: Early monitoring report

Report on baseline Child Care Package Evaluation project, early monitoring and emerging issues

August 2019

Jennifer Baxter, Megan Carroll, Kelly Hand, Mikayla Budinski, Cara Rogers, Jessica Smart

Download Research report

Overview

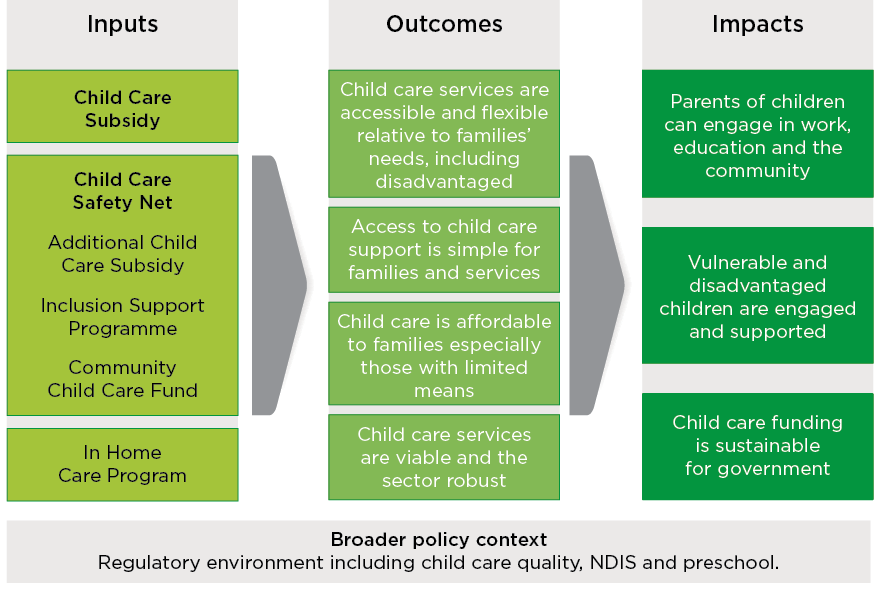

The Department of Education and Training has commissioned an evaluation of the new Child Care Package introduced in 2018. This is the first report of the evaluation, with a final report to be provided in 2021.

Child care in Australia has an extensive history, with the use of child care accelerating, in particular from the 1980s onwards. This expansion was driven by and contributed to increasing levels of workforce participation by women, including mothers and an increasing number of couple families with both partners employed. Key features of the expansion include:

- substantial increases in Commonwealth funding - commencing in the 1970s but building rapidly over more recent periods along with significant changes in the forms of financial support provided

- changes in the composition of child care provision including the growth in for profit providers and outside school hours care for school-aged children

- a stronger focus on the quality of care, and in more recent periods on the role of pre-school education

- ongoing cost pressures with the cost of child care provision rising much more rapidly than prices overall. The impact of this on the cost to parents has been mitigated by increasing levels of assistance.

The new Child Care Package introduced in July 2018 comprises:

- the replacement of existing payments with a single more generous, but more tightly income and activity tested Child Care Subsidy

- a Child Care Safety Net designed to reduce barriers to child care for disadvantaged families and communities

- enhanced information technology systems designed to simplify processes for parents and providers.

A key objective of the new Child Care Package is to boost participation in employment and employment enhancing activities.

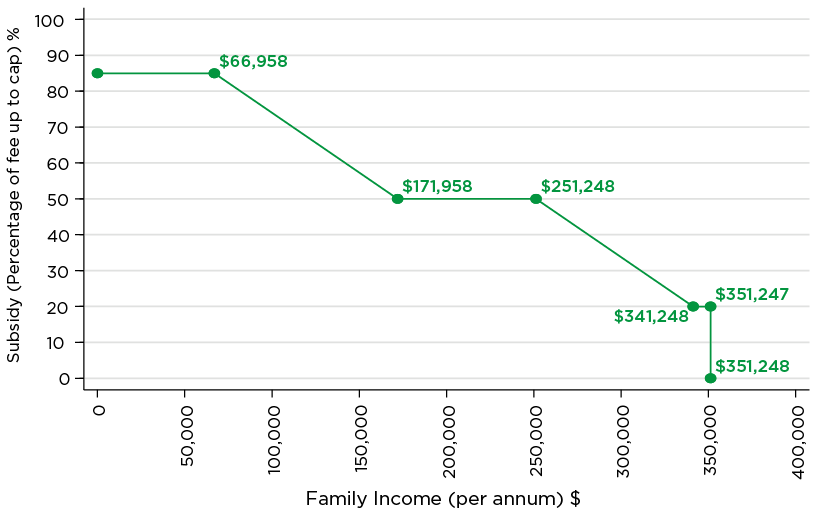

With the combination of more generous rates of subsidy and the introduction of enhanced activity and income testing, the package is expected to produce both winners and losers. Gains are anticipated for those on lower to middle incomes who undertake substantial workforce and other approved activities.

The introduction of the new program was accompanied by significant communication activities.

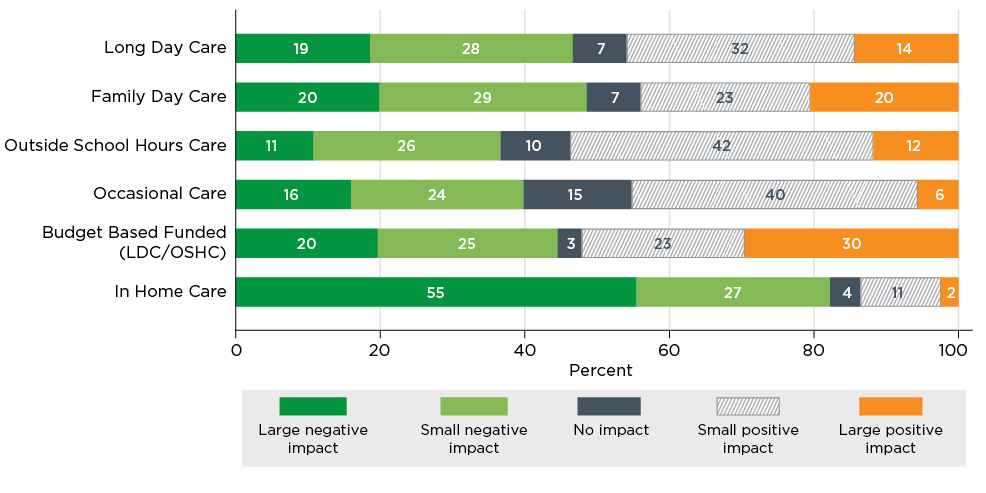

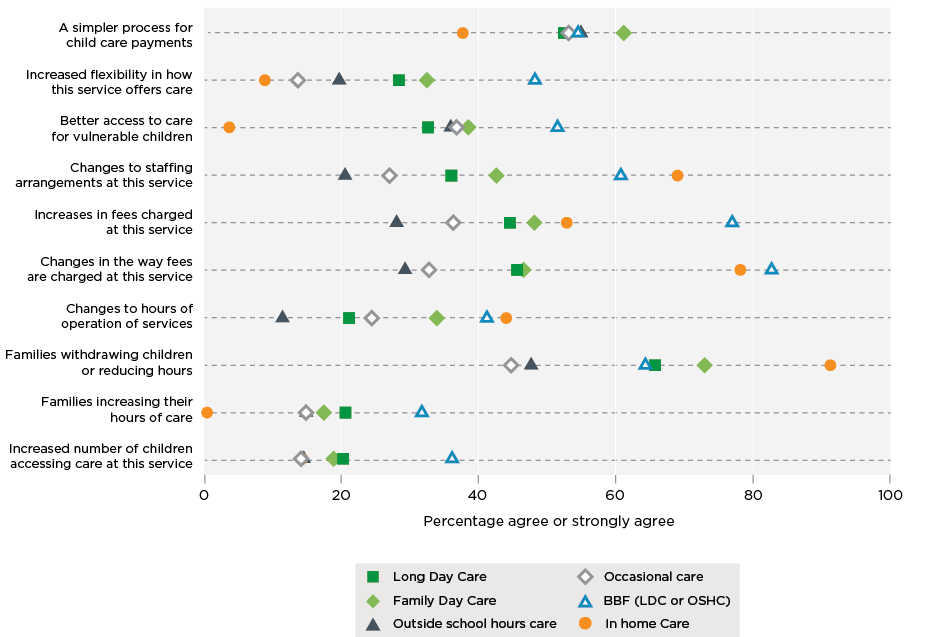

- Just prior to the transition some two-thirds of services considered that they were prepared for the change, although some 13 per cent said they were not.

- While 40 per cent felt that the package would have a positive impact 36 per cent felt that it would be negative, and many more felt that the package would result in parents reducing their use of child care than those who felt they would increase.

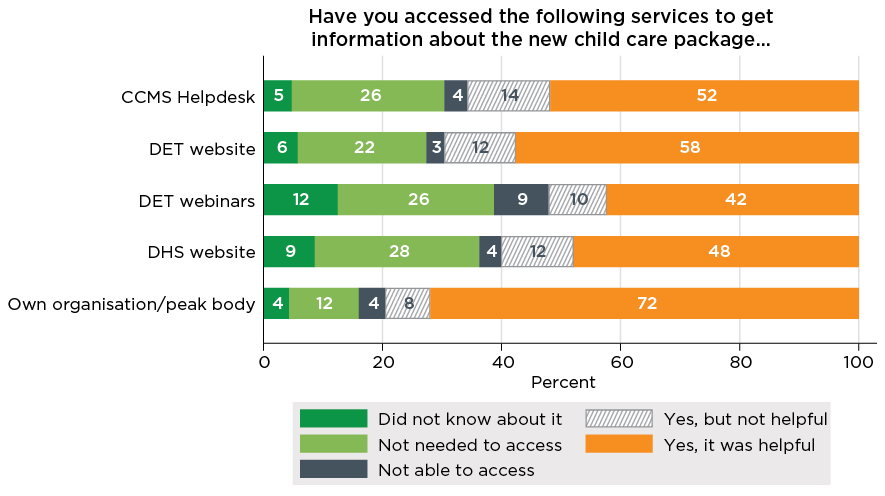

- Services rated the support provided by their own organisation or peak, and by software providers most highly with just under half reporting that they agreed or strongly agreed that the Department of Education and Training and Department of Human Services was providing enough support, with a quarter of services disagreeing. The majority had accessed Department of Education and Training communications activities.

- In general, while there were some differences by state and sector there did not seem to be large differences by either remoteness or the socio-economic level of the location in the attitudes and experiences of services.

Department of Education and Training data on the July 2018 transition of the child care system indicates that over 99 per cent of services transitioned to the new arrangements at the time of implementation.

- At the time of preparation of this report, only limited post-implementation information has been obtained from services, much of which has been qualitative in nature. Emerging themes are:

- There is a sentiment among services that the introduction of the package was onerous and placed a heavy burden upon them.

- Service providers expressed many concerns about the IT system, including with respect to PRODA and the limited pre-implementation opportunities services felt they had to become familiar with the system. Additionally, issues have been reported with regard to the operation of the Additional Child Care Subsidy.

- Many services, and some key stakeholders, have raised a concern about the potential impact of the activity test in reducing access to child care for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, specifically the impact of the provision of support for only 24 hours per fortnight, which for many services means a single day per week.

- To date while some services have introduced shorter sessions the charges for these are often relatively high.

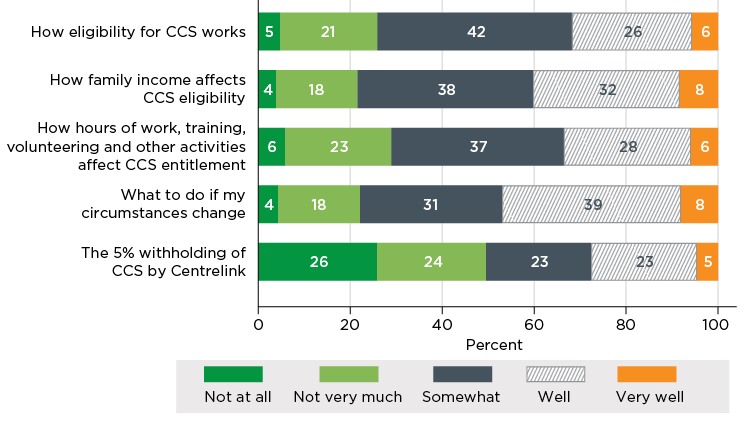

Parents generally considered that they were prepared for the new package and had accessed information. On balance they consider the package positively with 40.7 per cent describing it as being mostly or entirely positive, although 23.0 per cent considered it to be mostly or entirely negative.

- The majority reported that the transition process was relatively seamless, although around 20 per cent disagreed.

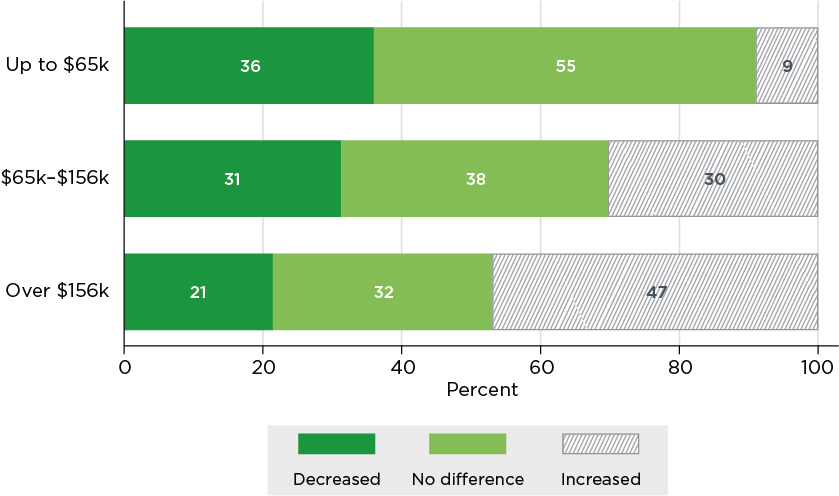

- Reflecting the expected impact of the changes, while most respondents report no or little change, low income families were more likely to report that their child care costs had decreased than high income families with this being reversed in terms of increased costs. While the currently available data is limited it suggests that some 42 per cent of families with incomes below $65,000 had experienced a fall in the cost of child care and 24 per cent an increase, for those on incomes between $65,000 and $170,000 the proportions were 39 per cent and 28 per cent, and for those with an income of over $170,000, 10 per cent and 65 per cent. According to Department of Education and Training data on families using child care, about 3 in 4 families have incomes below $170,000.

- To date most report no changes in their use of child care, nor in their level of engagement in employment.

These initial findings will be further scrutinised in the evaluation along with more detailed analysis of the transition and the impact and outcome of the new Child Care Package including on the costs of child care for families, changes in workforce participation, access to child care, especially for those with disadvantage, the robustness of the child care sector and the sustainability of government funding.

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| ABS | Australian Bureau of Statistics |

| ACCS | Additional Child Care Subsidy |

| ACECQA | Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority |

| AIFS | Australian Institute of Family Studies |

| AIHW | Australian Institute of Health and Welfare |

| ANU | Australian National University |

| ARIA | Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia |

| BBF | Budget Based Funded Program |

| CALD | Culturally and Linguistically Diverse |

| CAPI | Computer Assisted Personal Interview |

| CATI | Computer Assisted Telephone Interview |

| CBDC | Centre Based Day Care |

| CCB | Child Care Benefit |

| CCCF | Community Child Care Fund |

| CCSS | Child Care Subsidy System (formerly the Child Care IT System (CCITS)) |

| CCSS | Child Care Subsidy System |

| CCMS | Child Care Management System |

| CCPFamS | Child Care Package Families Survey |

| CCR | Child Care Rebate |

| CCS | Child Care Subsidy |

| CCTR | Child Care Tax Rebate |

| CPI | Consumer Price Index |

| CSP | Community Support Program |

| CWA | Complying Written Arrangement |

| DET | Department of Education and Training |

| DHS | Department of Human Services |

| DSS | Department of Social Services |

| ECCC | Early Childhood and Child Care |

| ECE | Early Childhood Education |

| ECEC | Early Childhood Education and Care |

| FDC | Family Day Care |

| GST | Goods and Services Tax |

| HILDA | The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics Study |

| IDF | Inclusion Development Fund |

| IHC | In Home Care |

| IPSP | Inclusion and Professional Support Program |

| IRSAD | Index of Relative Socio-Economic Advantage and Disadvantage |

| ISP | Inclusion Support Programme |

| IT | Information Technology |

| ITRG | Implementation and Transition Reference Group |

| IZA | Institute of Labor Economics (Germany) |

| JETCCFA | Jobs, Education and Training, Child Care Fee Assistance |

| LDC | Long Day Care |

| LinA | Life in Australia Study |

| LOTE | Language Other Than English |

| NDIS | National Disability Insurance Scheme |

| NFF-OCC | Non-Formula Funded Occasional Care |

| NHMRC | National Health and Medical Research Council |

| NQA ITS | National Quality Agenda Information Technology System |

| NQS | National Quality Standard |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| OSHC | Outside School Hours Care |

| PC | Productivity Commission |

| PEP | Provider Entry Point |

| PIR | Post Implementation Review |

| PolicyMod | Microsimulation Model of the Australian Tax and Transfer System |

| PRODA | Provider Digital Access |

| SCARC | Senate Community Affairs Reference Committee |

| SEIFA | Socio-Economic Indexes for Area |

| SELCS | Survey of Early Learning and Care Services |

| SES | Socio-Economic Status |

| SIP | Strategic Inclusion Plan |

| SNAICC | Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care - National Voice for Children |

| SPRC | Social Policy Research Centre |

| SRC | Social Research Centre |

| UNSW | University of New South Wales |

Child care plays an important economic and social role in Australia. For parents, it supports paid employment, education and training. For children, quality care can assist child development and has social and educational value, including a role in preschool education, particularly for vulnerable and disadvantaged children and their families. Since the 1970s the Australian Government has been active in providing support to the sector and the families using child care services. In 2018-2019 Australian Government expenditure, primarily through subsidies for the cost of care to parents, is with the introduction of the new package expected to be some $8.1 billion (Department of Education and Training, 2019, pp. 26-27).

In July 2018 the Australian Government introduced the 'new Child Care Package' under the aegis of the Family Assistance Legislation Amendment (Jobs for Families Child Care Package) Act 2017. The new Child Care Package has four key elements:

- Child Care Subsidy - this is the main form of financial support

- Additional Child Care Subsidy - additional fee assistance directed at families and children who may face barriers in accessing affordable child care

- Inclusion Support Programme - support for services to build their capacity and capability to include children with additional needs in mainstream services

- Community Child Care Fund - which enables grants to child care services to help them to address barriers to participation and to support service sustainability and funding for services in areas of high unmet demand.

The Additional Child Care Subsidy, Inclusion Support Programme and Community Child Care Fund, which are collectively referred to as the Child Care Safety Net are designed to provide additional targeted assistance for disadvantaged communities and vulnerable children and their families to address barriers to participation in child care and employment.

The Child Care Safety Net was progressively rolled out from July 2016. At this time the Inclusion Support Programme was introduced, as was the Connected Beginnings program, which is part of the Community Child Care Fund.

Another early element of the Child Care Package was the Nanny Pilot Programme, initially called the Interim Home Based Carer Subsidy Programme. A new In Home Care program was introduced in July 2018, which replaced the previous In Home Care program and the previous Nanny Pilot Programme.

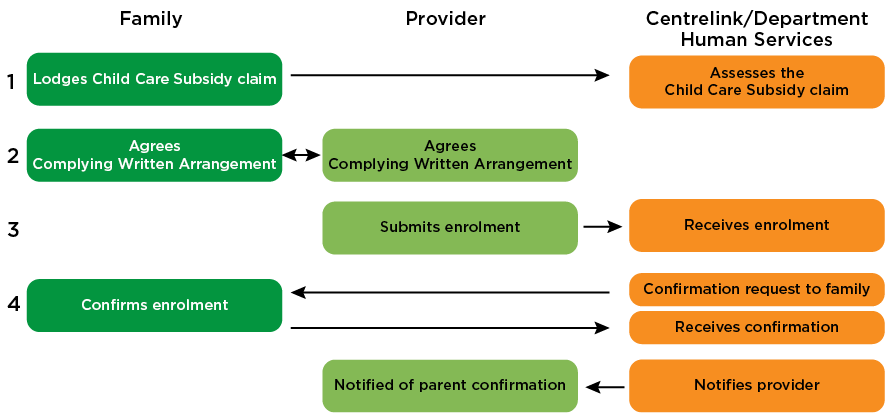

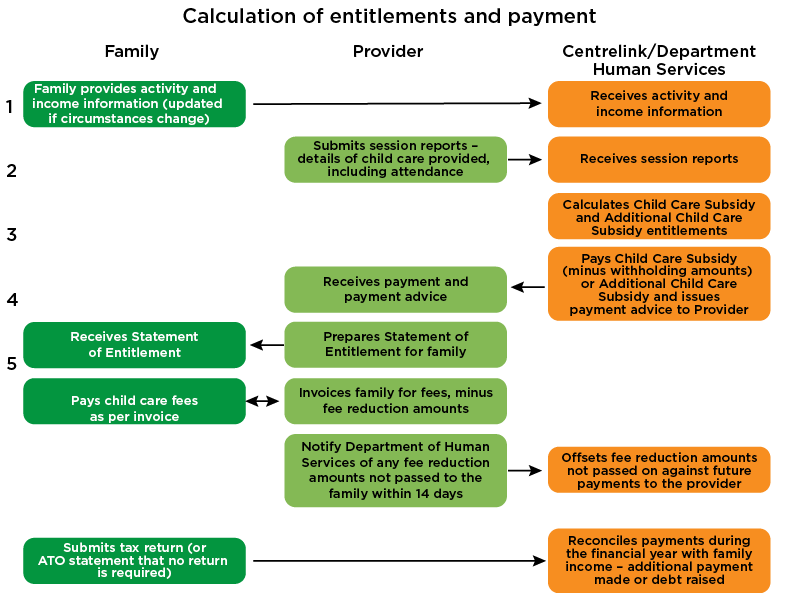

A new Information Technology system was developed with the intent of providing a simpler interface for both parents and services, and for the automation of the payment system. Changes have also been made to the child care services regulatory framework including the removal of some requirements related to hours of operation, and a strengthened set of requirements that services need to comply with (e.g. reporting on children's hours of attendance).

Underlying the package are the objectives of addressing issues of affordability and increasing costs, improving flexibility, and increasing the targeting of financial assistance, in particular towards supporting those parents who are participating in employment.

The Australian Institute of Family Studies in association with the Social Research Centre, the UNSW Social Policy Research Centre and the ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods have been commissioned by the Australian Government Department of Education and Training to undertake an independent evaluation of the new Child Care Package. The evaluation commenced in December 2017 prior to the introduction of the package and continues until June 2021. The In Home Care program and the Inclusion Support Programme, in addition to being within the overall evaluation scope, are being subject to specific attention and separate early findings reports for these programs will be completed by mid-2019, with a second In Home Care program report due mid-2020.

The evaluation is being guided by the Evaluation Framework which was agreed with the Department of Education and Training and which is publicly available.1 The Evaluation Framework, as detailed in Chapter 2, sets out four key outcomes and three key impacts against which the new Child Care Package is being evaluated. These reflect the policy objectives set by the government for the package. In large part they relate to medium to long term effects of the package and its consequences for families, children and the child care sector.

This early monitoring report is the first formal evaluation report. In addition to presenting early data about the transition for services and families it provides context for the reform package through a review of the history of child care in Australia and a detailed overview of child care provision and the nature and objectives of the Child Care Package at the point of implementation of the package. This context will be increasingly important as the evaluation progresses as a point of reference for understanding the progress and impacts of the reforms.

This report also provides baseline data on families with children and services, their expectations of about how the new system might work, their assessment of their readiness for the changes and some very initial data on the transition including parental labour supply responses and the costs of child care for families. The timing of this report means that it is only considering the immediate post-implementation period. It also means only limited administrative and other program data were available to the evaluation, and thus it is too early to assess the medium to long term effects.

The report is based on data collected either just before the introduction of the new Child Care Package or very shortly after the transition to the new arrangements. It draws upon:

- a range of data that describe the nature of the child care system, level of usage of child care, characteristics of those using the system, and costs of child care and how this has changed over time

- data collected from services just prior to the introduction of the new Child Care Package

- data collected from parents shortly before and shortly after the transition to the new system

- some limited administrative data on the transition of children and services to the arrangements under the new Child Care Package

- some preliminary data from interviews with key stakeholders and the pilot case study.

The Evaluation Framework anticipated that the Early Monitoring Report would be informed by and report on initial findings from the Post Implementation Reviews being undertaken by the Department of Education and Training. At the time of writing these have not yet been completed and thus have not been able to be drawn upon in this report. It was also anticipated that a range of administrative data covering the transition period would be provided to the evaluation consortium by the Department which would enable the immediate effects of the transition to be analysed. These data were not available at the time of writing the report. Given the absence of this information and that implementation of the new Child Care Package is in the early stages, it is not possible at this time to substantively address the key evaluation outcomes and impacts.

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

Background:

- Chapter 2 reviews the history and role of child care in Australia, including its relationship to increasing workforce participation in families with dependent children.

- Chapter 3 presents the evaluation framework and methodology.

- Chapter 4 provides information about the Child Care Package, as well as details of the sector at the point of transition including the broader environment in which it operates.

Initial analysis:

- Chapter 5 draws upon the data collections detailed above to consider the preparedness of services and providers for the introduction of the new package, and their attitudes and expectations of the impact.

- Chapter 6 complements the previous chapter by presenting findings related to families' expectations and experiences of the transition.

- Chapter 7 provides an early insight into the issues and experiences of the sector in the transition as drawn from the preliminary findings of the pilot case study and the current work of the evaluation in interviewing key stakeholders.

- Chapter 8 is a summary of the report. Reflecting the above considerations this chapter does not include any substantive findings as to the outcomes or impacts of the package, but rather some reflections on the state of child care at the transition and on the transition experience. It draws out a number of issues, which will be addressed at further stages of the evaluation.

2.1 Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the historical development of child care in Australia, the role of the Commonwealth in supporting and shaping its development, and hence the setting within which the Child Care Package has been introduced.2 The chapter provides an overview of the history of the development of the Australian formal child care system since 1970, including key policy developments and themes. Statistical information on key aspects of the development of the system are presented, although the extent to which it is possible to construct long time series is limited by the available data. Areas covered are size of the sector, the mix of types of child care, type of provider, and Commonwealth expenditure. The third section describes trends in the cost of child care. The fourth section provides a high level overview of families, their participation in the labour market and use and demand for child care. The fifth section provides an overview of the child care system in operation immediately prior to July 2018 when the new child care policy took effect.

The current rationale for Commonwealth involvement in child care is given in the 2017/18 Portfolio Budget Statement for the Department of Education and Training.

The program helps families to participate in the social and economic life of the community by:

- promoting and supporting quality and affordable child care

- assisting services to improve access and inclusion for vulnerable or disadvantaged children and families, including children with disabilities and their families

- supporting the sustainability of child care for all Australian children and families including in areas and/or under circumstances where services would not otherwise be viable

- developing, maintaining and disseminating information to assist families to make informed decisions about child care and the related support programs and services provided or funded by the government

- supporting child care services to be more responsive to the needs of families.

Types of child care

There are a range of different types of child care currently in Australia supported by the Australian Government. The main forms are:

Centre-Based Day Care

This is the predominant form of care usually being provided in purpose specific facilities, by either private providers, community organisations or local government, in the form of Long Day Care, or in some cases as Occasional Care. While Long Day Care services tend to offer whole of day care (typically 8 to 12 hours) to a relatively stable group of children, Occasional Care services focus more on casual or short-term provision.3

Family Day Care

Family Day Care is provided to small groups of children, usually in a Family Day Care educator's own dwelling. The provision of this service is structured with a single provider organisation managing a number of Family Day Care educators. These services are mainly provided by the private sector, although local government and not-for-profit providers play a significant role.

Outside School Hours Care

There are three forms of Outside School Hours Care, before school care, after school care and vacation care. These services are managed by private for-profit providers, schools, community and other organisations.

In Home Care

This is a small and specialised sector providing care in a family home for children in a range of circumstances where mainstream care is not available or appropriate.

Further details on these forms of care are given in Appendix B.

Other child care and early education and related services

In addition, reference is made to a number of other types of child care, including:

- Budget Based Funded Services. These are a group of services, largely serving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities which prior to July 2018 were directly funded by the Australian Government, rather than through fees income. Many of these services are transitioning to be Centre Based Day Care.

- The Nanny Pilot Programme. This was a form of in home care which operated as a pilot program between 1 January 2016 and 1 July 2018.

- Preschool and Kindergarten. As discussed in the text, these have traditionally focused on education rather than care services. This has changed so that today a high proportion of this preschool education is provided through Long Day Care services.

2.2 Overview of the history of Australian formal child care

In broad terms formal early childhood care and education can be divided into child care and kindergarten/preschool.4,5 The latter has primarily a more formal educational focus and aims to prepare children for school.

Child care, while largely having had a primary focus on allowing parental workforce participation, has also had a social development and educational component. The focus on social development and education in child care has grown in recent decades through the quality agenda that commenced in the early 1990s and associated initiatives such as the National Quality Framework. While the scope of this chapter focusses on formal child care, it needs to be recognised that there is an interaction between preschool and child care services, and increasingly, child care services are providing formal preschool programs.

In Australia, kindergartens emerged in the 1890s with the Kindergarten Union establishing the first formal early childhood teacher training program in Sydney in 1897 (Brennan, 1998). The early kindergartens were intended to assist children living in families experiencing poverty (Brennan, 1998). There was growth of kindergartens during the 1950s with the focus shifting from assisting children from deprived backgrounds to becoming an important part of early childhood education (Press & Hayes, 2000).

Child care had its origins in the Day Nursery Movement which also emerged in the late 1890s, with a focus on assisting disadvantaged families (Press & Hayes, 2000). However, there was only very limited formal child care until the 1970s.

1970 to 1983

In 1970 there were 560 registered child care centres in Australia offering about 14,000 places (Brennan, 1998). Forty of the centres received support from state/territory governments with virtually no Commonwealth support. Almost all of the centres were run as for-profit centres and were established to provide care for children from deprived or underprivileged backgrounds. Outside school hours care has existed in some form for decades, but government funding for this type of care did not commence until the 1970s (Moyle, Meyer, & Evans, 1996).

At this time there were increases in maternal employment and strengthening evidence and recognition that a lack of child care was a significant barrier to mothers being able to return to, and maintain, employment. In 1972 the Commonwealth Child Care Act was passed and this allowed the Commonwealth to provide funding to not-for-profit organisations to run centre-based day care facilities for children of working and sick parents (McIntosh & Phillips, 2002). This reflected recognition of growing employment rates of mothers and the importance of providing good quality care at an affordable price, especially for single parent families, newly arrived migrants, low-income families, and disabled parents (Senate Community Affairs Reference Committee [SCARC], 1998).

In 1974 a decision was made to extend Commonwealth government financial support for all child care, not just that for families that were poor or needed financial assistance. This marked a change in the philosophical underpinning of the provision of child care. The Commonwealth continued to expand financial support over the following years, expanding the range of organisations that could receive assistance and including new child care services and forms of child care other than child care centres including preschools, Family Day Care, Outside School Hours Care and playgroups (McIntosh & Phillips, 2002).

In 1976 the Commonwealth ceased directly funding individual centres and instead provided block funding to states and territories; representing a major change (SCARC, 1998). The effect of these changes was that during the period from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s expansion in child care places was mainly in Family Day Care (McIntosh & Phillips, 2002). The period 1976 to 1980 was one of declining Commonwealth expenditure on children's services (SCARC, 1998).

1983 to 1996

From 1983 there was a progressive increase in the number of child care places as a result of additional Commonwealth funding including the National Children's Services Program in 1983, and the National Childcare Strategy in 1988. In 1982 there were around 41,600 Commonwealth supported child care places and by 1991 this had increased to 168,300 places (Brennan, 1998).

In 1984 financial assistance for non-profit Long Day Care centres was introduced. This was subsequently extended during the 1980s and became the main form of Commonwealth financial support for child care (McIntosh & Phillips, 2002). There was also a shift towards a more needs-based planning approach to the expansion of Commonwealth support for child care places and in 1985 the Commonwealth ceased block funding for states and territories for preschools (McIntosh & Phillips, 2002).

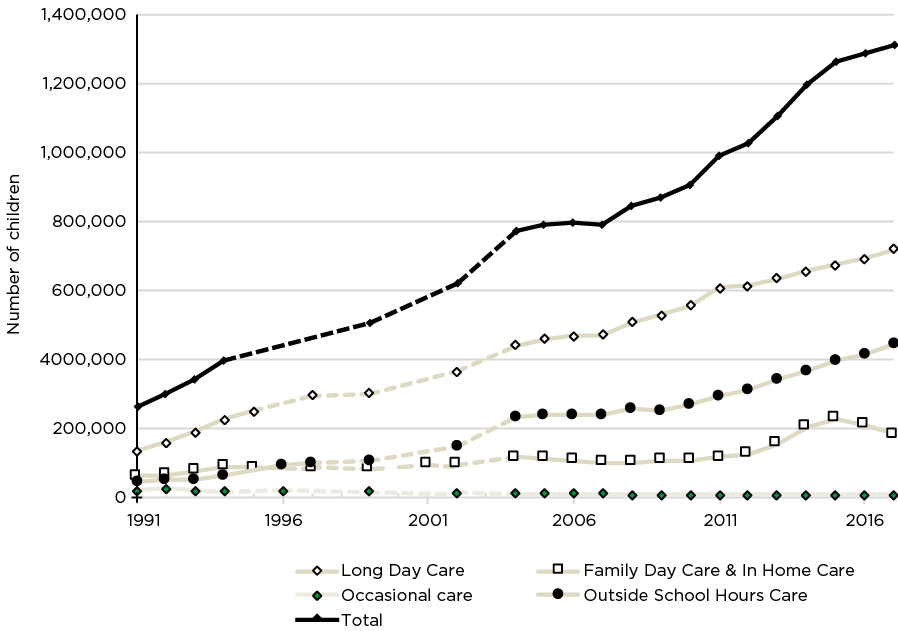

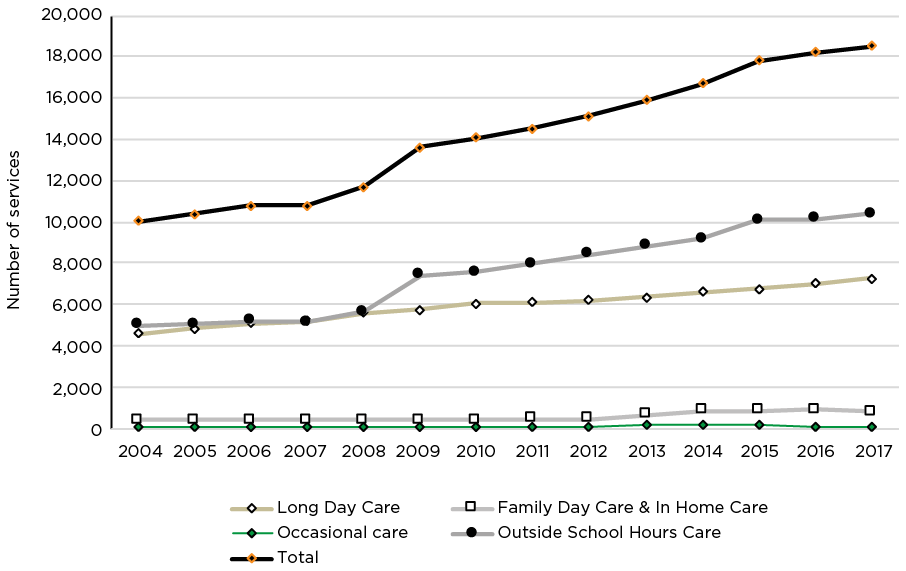

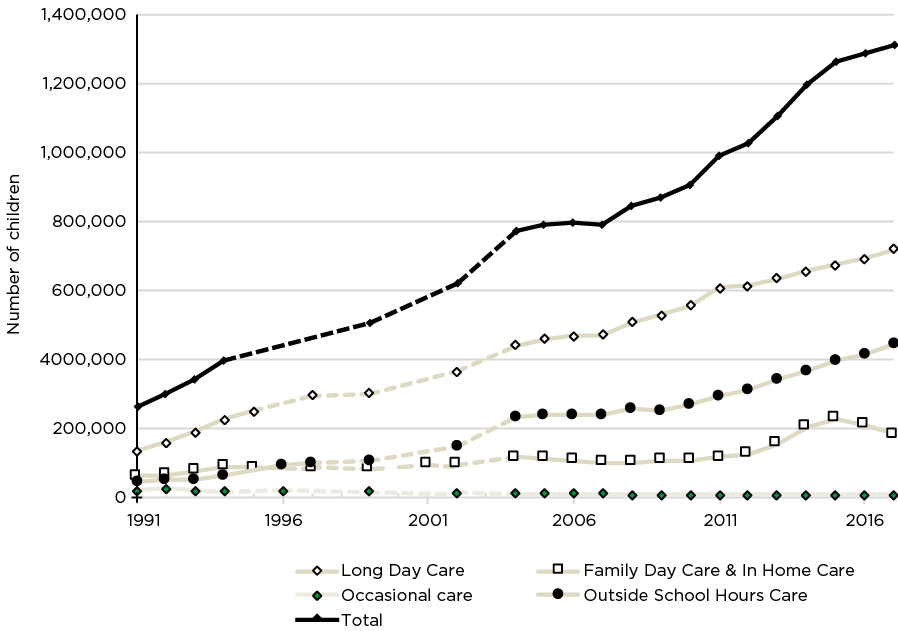

The 1990s saw a further expansion of Commonwealth funded child care places (Figure 2.1) and an increase in the number of services (Figure 2.2). In 1990 the National Childcare Strategy was expanded to allow for an additional 50,000 child care places by the mid-1990s. A significant change was to extend fee relief to commercial child care centres in 1990. This led to a large expansion in the number of Long Day Care centre places (SCARC, 1998). Over the period 1994 to 1996 the Commonwealth provided funds to local government and community organisations so as to increase the number of work-related child care places, including Outside School Hours Care (SCARC, 1998).

In 1993 the introduction of an accreditation scheme for child care centres was announced and the Accreditation Council established, and in 1994 the Quality Improvement and Accreditation System was introduced. This was aimed at improving the quality of approved child care (SCARC, 1998). Also in 1994 the Childcare Cash Rebate was introduced. This was paid to families to assist with the costs of work-related child care assistance (SCARC, 1998).

Figure 2.1. Number of children using child care by service type, 1991 to 2017

Sources: Data for 1991 to 2002 are from AIHW (2003), Table 6.12. Data for 2004 to 2012 are from Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (2013), Child Care in Australia, August 2013, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. Data for 2013, 2014 are from Child Care and Early Learning in Summary published by the Department of Education. Data for 2015, 2016 and 2017 are Department of Education and Training publication Early Childhood and Child Care in Summary.

Notes: For the period 1991 to 2002 Occasional Care includes multifunctional Aboriginal Children's services and other multifunctional services. The data for this period measure occurrences of care and includes some double-counting where children attend more than one services. Data from 2004 are for the September quarter. Data for the period 1995 to 2003 are not necessarily complete or consistent. This is shown here by a dashed line.

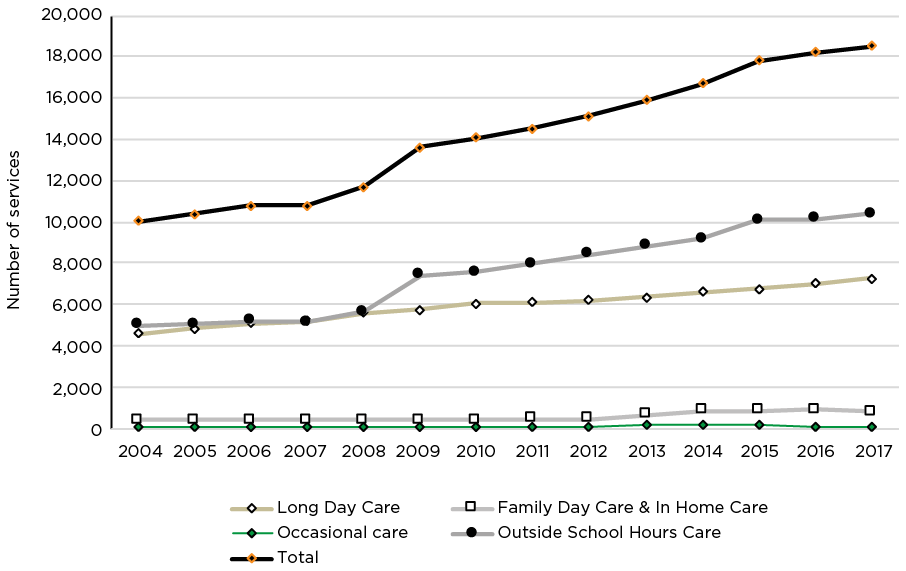

Figure 2.2. Number of services by type of services, 2004 to 2017

Sources: Data for 2004 to 2012 are from Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (2013), Child Care in Australia, August 2013, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. Data for 2013, 2014 are from Child Care and Early Learning in Summary published by the Department of Education. Data for 2015, 2016 and 2017 are Department of Education and Training publication Early Childhood and Child Care in Summary.

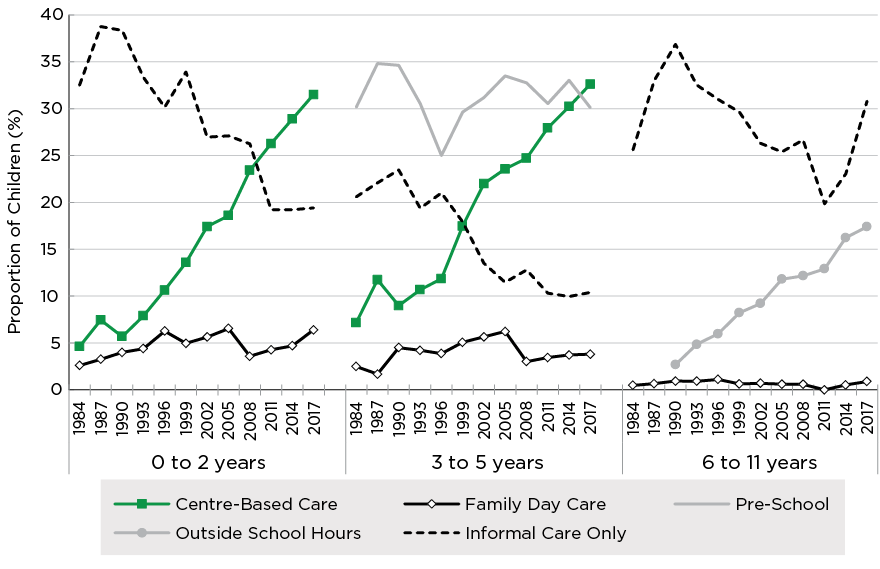

Figure 2.3 shows child care use by child age and type of child care (including informal care only) for the period 1984 to 2017. Growth in maternal employment and dual earner families with children (see discussion in section 2.4), and the growth in the child care sector over this period is reflected in the big increases in the proportion of children attending different types of care. The proportion of children aged 0 to 2 years attending centre-based care increased from 4.6 per cent in 1984 to 31.5 per cent in 2017 and the proportion attending Family Day Care increased from 2.6 per cent to 6.4 per cent over this period. For children 3 to 5 years, the proportion attending centre-based care increased from 7.2 per cent to 32.6 per cent over the period 1984 to 2017, the proportion attending Family Day Care increased very slightly from 2.5 per cent to 3.8 per cent, and the proportion attending preschool fluctuated but was around one-third over the period. There was a big increase in the proportion attending Outside School Hours Care from close to zero to 17.4 per cent.

The increased use of these forms of care has meant a decline in the number of children only using informal care arrangements, such as care by grandparents. Nevertheless, Informal care arrangements remain common for children of all ages, often used in combination with formal arrangements like long day care, family day care and outside school hours care (Baxter, 2015).

Figure 2.3. Child care use by child age and type of child care, 1984 to 2017

Source: Bray (2018). Underlying data from ABS 4402.0

Since 1997

Following a change of government in 1996, major changes were made to Commonwealth child care policy and funding including: the removal of operational and capital works subsidies for community owned Long Day Care centres; the limiting of Childcare Assistance - as provided under the Commonwealth Childcare Assistance Scheme - to 50 hours per week per child; freezing the levels of Childcare Assistance and the Childcare Cash Rebate for two years; and the reduction of the Childcare Tax Rebate from 30 per cent to 20 per cent for families with an income above a certain level (SCARC, 1998).

The removal of operational and capital works subsidies reflected a view that child care subsidies should be used to help parents purchase whatever form of accredited child care best suited their needs. It also reflected a view that the changes 'would encourage community centres to be more efficient and cost competitive with the private sector' ... [and also] ...'to remove inequities in government assistance for families using private and community-based centres' (Department of Health and Family Services, 1996, pp. 178-188).

The 1997-98 budget represented the start of a trend towards varying the level of subsidy between working and non-working parents, with changes including limiting Childcare Assistance to 20 hours per week for each child using child care for parents' non-work purposes (McIntosh & Phillips, 2002).

In 2000 the cap on Long Day Care places was removed and since that time there has been no controls on the number of Long Day Care places or the location of new centres. This was intended to encourage market competition and to offer choice to families. The caps on Family Day Care and Outside School Hours Care places were removed in July 2006.

Also, in 2000, significant changes were made to the tax system (associated with the introduction of the GST). At this time Childcare assistance and the Childcare Cash Rebate were replaced with the Child Care Benefit. The Child Care Benefit was more generous than the payments it replaced and the income threshold for eligibility was raised and the number of hours of subsidised care was increased. Child Care Benefit was available either as direct payments to parents or as lump sum payment at the end of the year (Whiteford, Stanton, & Gray, 2001).

The 2000-01 Commonwealth Budget provided funding for a number of new child care initiatives that overall had an emphasis on more flexible services being provided and more services being made available in rural and remote areas. Specific measures included:

- the introduction of a new In Home Care measure for those families for whom accessing standard childcare services was difficult

- extending the quality assurance to Family Day Care and Outside School Hours Care

- the Long Day Care Incentive Scheme, which encouraged private operators to establish child care centres in rural and urban fringe areas of high, unmet demand.

In 2004 the Child Care Tax Rebate was introduced. This payment covered 30 per cent of out-of-pocket expenses for approved child care where parents met a work, study or training test. Expenses were calculated after the Child Care Benefit was taken into account. Initially the payment covered 30 per cent of the costs and was capped at $4,000 per child per year.6 Initially the Child Care Tax Rebate was a non-refundable tax rebate and could be claimed in the tax return of the following year. In 2007 the Child Care Tax Rebate was removed from the tax system and became a cash payment after the end of the financial year in which the child care costs were incurred. There were also changes made that increased the generosity of the Child Care Tax Rebate. The key changes to the level of the Child Care Tax Rebate were increasing the maximum value of the rebate from $4,354 in 2007-08 to $7,500 per child per annum in 2008-09 and then subsequently slightly reducing the rebate (from $7,941 in 2008-10 to $7,500 in 2011-12) and freezing its maximum level until July 2017.7 There was also an increase in the proportion of out-of-pocket child care expenses covered from 30 per cent to 50 per cent up to the cap from July 2008. In June 2018 the Child Care Rebate covered 50 per cent of out-of-pocket child care expenses up to the annual limit of $7,613 per child per year.

Other than some changes in the way that the Child Care Tax Rebate was paid, and an increase in the percentage of families' out-of-pocket costs it paid for, the child care payment system remained relatively unchanged from 2004 until 2 July 2018 when the Child Care Benefit and the Child Care Tax Rebate were replaced with the single Child Care Subsidy (see Chapter 3 for a description of the Child Care Subsidy and other changes that took effect from 2 July 2018). One policy which did however impact on parts of the child care system was the application of enhanced anti-fraud measures, especially in the Family Day Care sector from 2014. These are discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.

The Community Support Program, introduced in 2004, provided funds to Family Day Care, Occasional Care and In Home Care services to help with set-up costs and also provided 'sustainability assistance' to these services and to Long Day Care services (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, 2015). In addition, the Community Support Program provided most Family Day Care services with operational assistance in recognition of the additional costs associated with the support and oversight of educators by the service. However, massive growth in the number of Family Day Care services led to rapidly escalating costs for the program. In response, eligibility was tightened in 2014 and 2015, restricting program access to Family Day Care services operating in the most disadvantaged areas or in rural and remote areas. As a result, most Family Day Care services lost this as a significant source of funding and redesigned their fee structures as well as the nature of the support they offered educators (Cortis et al., 2014). The Community Support Program ceased in June 2018, with the introduction of the Community Child Care Fund in July 2018.

The changes to the system that were designed to encourage a greater level of market competition resulted in a rapid increase in the proportion of Long Cay Care centre places being provided for profit providers including the growth of large providers (one of the first was ABC Learning, which increased from 43 centres in 2001 to 1,037 at the time it collapsed and went into administration in November 2008).8 At its peak ABC Learning provided around 25 per cent of the Long Day Care market, providing care to over 100,000 children.

Productivity Commission data report that, as of 30 June 2016, 62.5 per cent of Long Day Care centres and 78.4 per cent of Family Day Care services were run by private for profit providers. Community sector providers operated 29.8 per cent of Long Day Care centres and 12.8 per cent of Family Day Care services (Figure 2.4). There is a more even mix of provider types for Outside School Hours Care (before and after school care). The community sector runs 40.4 per cent of vacation care services and 34.3 per cent of Outside School Hours Care and the private sector 41.0 per cent and 46.0 per cent respectively. Government schools as well as non-government schools are also significant providers with 6.5 per cent of vacation care and 7.0 per cent of Outside School Hours Care provided by non-government schools and 12.1 per cent and 12.7 per cent respectively provided by state, territory or local government.

Figure 2.4. Type of service by type of provider, June 2016

Source: Productivity Commission (2017), Table 3A.10

While it is difficult to obtain consistent data over time on the proportion of children in services run by private for-profit providers and on the proportion in community sector run services, it is clear that the proportion in private for-profit services increased substantially during the 1990s. In 1991 about half (48.1 per cent) of Long Day Care centres were run by private for-profit providers, this had increased to 74.7 per cent in 1997 and was 71.6 per cent in 2004 (AIHW, 2005). Data from the Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority (2018) for September 2018 show that 66.0 per cent of children attending a Long Day Care centre were attending a privately run centre.9

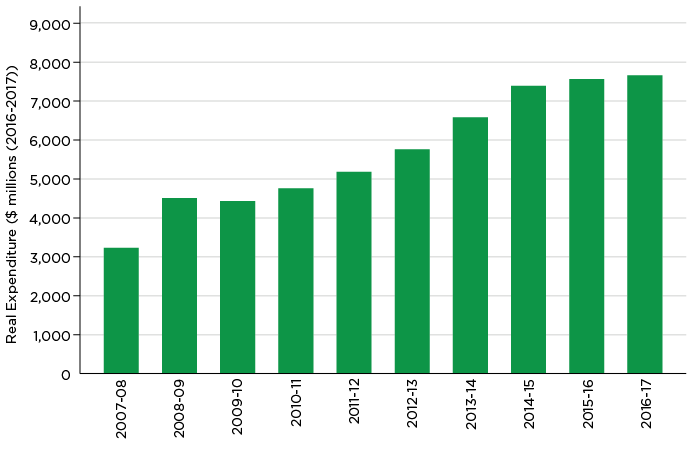

The real value of Commonwealth expenditure on child care increased from $3.2 billion in 2007-08 to $7.7 billion in 2016-17 (expenditure in 2016-17 dollars) (Figure 2.5). This is an increase in real expenditure on child care of 137 per cent, much faster than the growth in the number of children aged 0-12 years, which increased by 15 per cent over the period 2007 to 2016 (Productivity Commission, 2018, Table 3A.2).

Figure 2.5. Real Commonwealth expenditure on child care, 2007/08 to 2016/17, Australia

Source: Productivity Commission (2018), Table 3A.6

Standards and Quality

A significant development in the child care landscape was the Commonwealth and state and territory governments signing the National Partnership Agreement on Early Childhood Education in 2008. While not directly a child care measure, it aimed to provide universal access to preschool in the year before full-time school and it had implications for the child care sector. One consequence was an increased focus on the quality of child care, and the early education role of child care, including the introduction of two national frameworks: the Belonging, Being, Becoming - Early Years Learning Framework for young children in 2009; and the My Time, Our Place Framework for School Aged Care in 2011. This also marked a growing awareness of the importance of preschool programs offered in child care services, as most children in New South Wales (NSW), Victoria and Queensland access preschool in Long Day Care services (Pascoe & Brennan, 2017). Of particular significance is the 2010 National Partnership Agreement on the National Quality Agenda for Early Childhood Education and Care, which endorsed a National Quality Standard for child care, the establishment of a national rating system, and the establishment of national body responsible for guiding the implementation and management of the system. The quality framework identified seven key quality areas:

- Educational program and practice

- Children's health and safety

- Physical environment

- Staffing arrangements

- Relationships with children

- Collaborative partnerships with families and communities

- Leadership and service management.

Subsequent to the agreement, the Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA) was established to undertake a national coordinating role. This is an independent national authority managed by a governing board whose members are nominated by the Australian and state governments. The authority works closely with the state and territory regulatory authorities who grant approvals for services and assess services against the National Quality Standard.

The National Quality Standard provided national consistency in quality requirements for all formal services. It established, with a rolling timetable for achievement, regulations on educator to child ratios, staff qualifications, and requirements for all educators, including Family Day Care educators, to document children's learning for families and to feed this information into educational programming.

A revised National Quality Standard was introduced in February 2018. This reduced the number of standards from 18 to 15, reduced the elements from 58 to 40, and was designed to clarify the language and ensure that each standard and element described a single unique concept. This was accompanied by some changes in the rating framework and implementation. Other changes, some of which were implemented from late 2017 in most states, concerned improved oversight of Family Day Care, and the introduction of a national educator to child ratio for the provision of care to school-aged children. In the 2018-19 Budget, the Australian Government provided funding to ACECQA for two years to support quality and drive continuous improvement in the sector.

Productivity Commission Inquiry into Child Care and Early Childhood Learning and policy response

In 2013 the Productivity Commission was requested by the government to undertake an Inquiry into Child Care and Early Childhood Learning. This inquiry had broad terms of reference which reflected the commitment of the Australian Government 'to establishing a sustainable future for a more flexible, affordable and accessible child care and early childhood learning market that helps underpin the national economy and supports the community, especially parent's choices to participate in work and learning and children's growth, welfare, learning and development' (Productivity Commission, 2014a, p. iv).

The Productivity Commission reported in 2014 and noted that while 'there is a lot that is good about Australia's current ECEC (Early Childhood Education and Care) system … the current ECEC funding system was largely designed to meet the needs of a different era and the series of incremental additions and amendments mean there is much scope for improvement' (p. 6). The report concluded that the 'current ECEC arrangements are complex and costly to administer and difficult for parents and providers to navigate'.

A range of specific issues and recommendations were identified, including those relating to the complexity of child care subsidies (for services, providers and families), as well as access to and affordability of child care for some families. The key recommendations of the Inquiry concerned a new approach to funding which had three main elements:

- 'mainstream support through a single child-based subsidy that is: means- and activity- tested, paid directly to the family's choice of approved services, for up to 100 hours per fortnight, and based on a benchmark price for quality ECEC. In regional, rural and remote areas with fluctuating child populations, viability assistance should be provided on a limited time basis

- support [for] the inclusion of children with additional needs in mainstream services, delivery of services for children in highly disadvantaged communities and the integration of ECEC with schools and other child and family services

- approved preschool programs funded on a per child basis, for all children, regardless of whether they are dedicated preschools or part of a long day care centre' (Productivity Commission, 2014b, p. 2).

More generally the Productivity Commission noted that 'Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) services play a vital role in the development of Australian children and their preparation for school, and in enabling parents to work' (p. 2). With respect to workforce participation, while identifying that some increase was likely to occur, this was likely to be 'small'.

Indeed, in their summary, the Productivity Commission noted that while it had 'estimated that there may be up to roughly 165,000 parents (on a full-time equivalent basis) who would like to work, or work more hours, but are not able to do so because they are experiencing difficulties with the cost of, or access to, suitable child care', they expressed some caution: 'as workforce participation is affected by many factors other than ECEC (including flexible work arrangements, other government family payments and support of partners), the accessibility and affordability of ECEC and ECEC assistance arrangements are important, but not the only factors, that discourage parents from working.' (Productivity Commission, 2014b, p. 11).

In their substantive considerations of these issues they emphasised a series of trade-offs including 'reductions in unpaid work currently performed by mothers, reductions in the workforce participation of fathers and those providing informal child care … and the added stresses in achieving work-life balance' (Productivity Commission, 2014a, p. 186). The Productivity Commission Report also notes, 'The workforce participation of mothers of children aged under 15 years is affected by the preferences of parents to look after their own (particularly very young) children' (p. 231). They estimated that if their proposed model for child care was introduced this could 'increase the labour supply of mothers by 1.2 per cent - the equivalent of around … 16,000 full-time equivalent workers' (p. 670) and generate an increase in GDP of '$1.3 billion in 2013-14 (or 0.1 per cent of GDP)' (p. 684). In considering these impacts they caution 'pursuing an objective of supporting workforce participation through an ECEC system should not be divorced from another important objective - namely, enabling greater child learning and development' (p. 186).

In response to the Productivity Commission Report the government announced the Jobs for Families Child Care Package in the 2015-16 Budget. This led to the program changes (which are considered in this report) which commenced on 2 July 2018. The Jobs for Families Child Care Package is described in more detail in Chapter 4.

2.3 Trends in the cost of child care

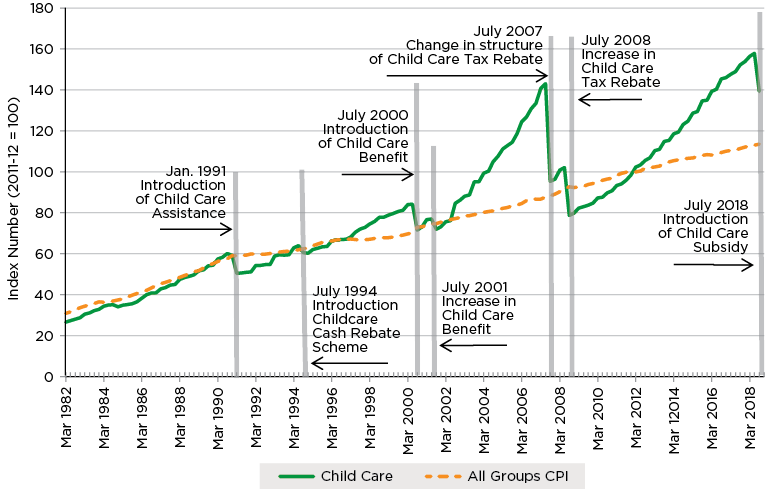

The history of the cost of child care as measured by the Australian Bureau of Statistics' Consumer Price Index is, as illustrated in Figure 2.6, one of rapidly increasing prices (especially since the early 1990s) punctuated by strong price falls as Commonwealth Governments have increased the generosity of payments or introduced new programs.

Figure 2.6. ABS Child Care and All Groups CPI, March 1982 to September 2018

Source: ABS 6101.0

Interpreting these changes requires an understanding of the methodology that the ABS uses to calculate price change for child care. The ABS methodology involves collecting gross child care prices and then subtracting government child care payments. Government child care payments are calculated through the use of customer profiles for a sample of households. The methodology takes into account payments that are made to families that reduce child care costs to families, but not assistance provided through the tax system.

Specifically highlighted in Figure 2.6 are some of the major changes. The ABS report these changes as:

- a fall of 14.7 per cent in child care fees in the March quarter 1991. This was as a consequence of the introduction of Childcare Assistance in January of that year (effectively the extension of the 'Fee relief' which has been available in the community sector)

- a 5.1 per cent decrease in the September quarter 1994. This was 'largely due to the introduction of the Commonwealth Government Childcare Cash Rebate Scheme that came into effect on 1 July 1994' (ABS 6401.0 September 1994, 2)

- a fall of 15.1 per cent in the September quarter 2000. No detailed explanation of this is given by the ABS, in part as this release also encompassed the effect of the introduction of the GST. The change appears to reflect the impact of the introduction of the Child Care Benefit and the higher rates of assistance this provided

- a fall in September 2001. ABS reported 'a fall in the cost of child care (-6.4 per cent) due to an increase in Commonwealth child care benefits' (ABS 6401.0 September 2001, 4)

- a fall of 33.4 per cent in September quarter 2007. The ABS reports this as resulting 'from a change in the eligibility criteria for the Child Care Tax Rebate (CCTR) that has brought it in-scope of the CPI this quarter and from the additional 10 per cent indexation of the Child Care Benefit (CCB) rates on top of the usual annual CPI indexation' (ABS 6401.0 September 2007, 1)10

- a further fall of 22.9 per cent in the September quarter 2008. This is ascribed by the ABS to 'the increase in the Child Care Tax Rebate (CCTR) from 30 per cent to 50 per cent that was implemented as of 1 July 2008' (ABS 6401.0, September 2008, 5)

- a fall in September 2018. The ABS reported the introduction of the Child Care Package and the CCS as resulting in an 11.8 per cent decline in the cost of child care: 'The fall in child care is due to the introduction of the Child Care Subsidy from 2 July 2018, which replaced the Child Care Rebate and Child Care Benefit' (ABS 6401.0, September 2018, 3).

These changes in support have had a profound effect on affordability. While the annualised nominal rate of increase in child care costs since March 1982 has been 4.7 per cent, this is estimated to increase to 8.3 per cent if the effect of these identified increases in support (and ignoring any other adjustments outside of these events) is excluded. In real terms (i.e. taking account of other price increases), over this period the annualised increase in cost of child care as measured by the CPI has been 1.0 per cent, and 4.5 per cent when these changes in assistance have been removed. That is, these increases in assistance over a number of decades have been a major factor in reducing the cost impact of child care on consumers.

Over the period since June 2001 the annualised rate of real growth in child care costs as reported by ABS has been 1.0 per cent and once the effects of the policy changes are removed, this increases to 6.2 per cent.

As well as reflecting child care specific issues, this much higher underlying increase in the cost of child care can be seen as reflecting wider factors in the drivers of price change in Australia. One dimension of this can be seen in the relative changes in prices of 'Tradeable' and 'Non-Tradable' components of the CPI. While the price of items in the tradeable sector (i.e. goods and services with exposure to international trade) increased by 30.5 per cent between June 1998 and September 2018, prices in the non-tradable sector (i.e. without this type of exposure) increased by 101.0 per cent, with the overall CPI, which is a balance of these two sectors increasing by 68.4 per cent. That is, the fact that the cost of a domestically produced service such as child care has increased more rapidly than the CPI is not unusual.

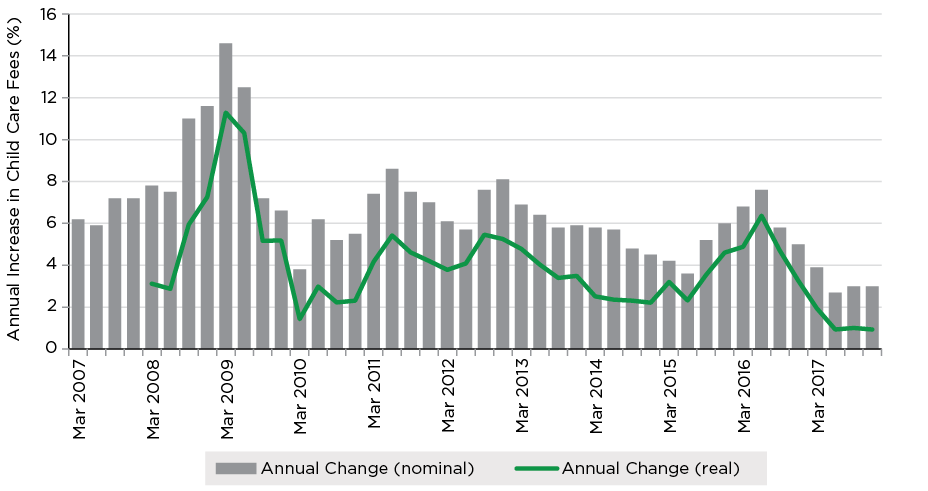

A second series examining the cost of child care by looking at average fees charged by services is produced by the Department of Education and Training. Currently data are published for the period March 2007 to December 2017. As illustrated in Figure 2.7, the series shows a diversity of change over this period, although demonstrating that for the whole period the rate of real growth in child care fees has been positive. In addition to the strong peak in real increases seen in March 2009, lesser peaks were recorded in June 2011 and September 2012, and again in June 2016. After this last peak the rate of real growth in fees appears to have declined, in particular in the year to the last two quarters of 2017.

However, growth in fees was not consistent across sectors. Annualised real growth rates in fees for the period March 2007 to December 2017 ranged from 3.0 per cent for Occasional Care to 4.0 per cent for Long Day Care (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.7. Nominal and real rates of annual growth in Child Care Fees (all sectors) March 2007 to December 2017

Sources: Derived from Department of Education and Training Early Childhood and Child Care in Summary Reports (various) & ABS 6401.0

Figure 2.8. Annualised real increase in child care fees by sector, March 2007 to December 2017

Sources: Department of Education and Training Early Childhood and Child Care in Summary Reports (various)

2.4 Families, child care and the labour market

This section considers the relationship between child care and workforce participation and provides a high-level summary of trends in maternal employment, discusses how families make work force participation and child care decisions, and considers the impact of children on maternal employment.

Child care, maternal employment and other outcomes

This chapter has already detailed the perspective of the Productivity Commission on the relationship between child care and maternal employment. These issues were also explored in Baxter, Hand, and Sweid (2016), who focused on decision making in respect to flexible work and flexible care and Hand (2007) who explored the ways that couples make decisions about work and care arrangements. These reports discuss the roles of child care affordability, availability and flexibility in relation to parents' use of care and parents' employment. They also highlight that decisions about work and care are also strongly influenced by parents' own views of parenting and gender roles. For example, Baxter et al. (2016) discuss the strong gendered parental norms that still contribute to decision making about work and care in Australia, such that mothers often prefer part-time work or to take time away from paid work while children are young. For some families, these attitudinal factors are more influential than are factors related to the accessibility or affordability of alternate care options.

Taking a wider perspective from the international literature, the German Institute of Labour Economics (IZA) summary of the cross-national evidence on the relationship between child care policies and maternal employment (Vuri, 2016) concludes that:

- countries with a higher availability of affordable child care exhibit high maternal labour force participation rates

- the provision of child care, especially for preschool-aged children, helps mothers achieve a satisfactory work−life balance

- higher child care subsidies result in a substantial increase in child care utilisation

- larger labour supply effects occur in countries where employed single parents or two-earner couples are eligible for the [child care] subsidies.

However, in terms of looking at the implications of further policy development the paper noted:

- the scope for policy to increase labour supply is limited in countries with very high female labour force participation and/or highly subsidised child care systems

- good access to affordable care might result in little or no increase in maternal labour supply if it only crowds out other forms of non-parental care

- difficulties in measuring the lack of qualified people working in child care and the quality of care may prevent families from using this service

- preferences and social norms may drive child care choices, as well as costs and availability.

Australia has several of the characteristics that are associated with child care policies having a greater impact on maternal employment including maternal employment rates around the middle of OECD countries and the fact that many families face significant out-of-pocket child care costs (Vuri, 2016, p. 1).

A recent study presents an overview of economic studies of the outcomes of pre-kindergarten programs undertaken in the United States.11 The studies included in the research were all 'scaled up' projects, rather than smaller experimental studies. This indicated that almost all of the programs had positive cost-benefit outcomes, with a high proportion having returns of two or three times the cost (Karoly, 2017, p. 63). Summary results are shown in Table 2.1. This reports on the 'monetarised outcomes', that is the estimated dollar value of the gains and costs of these programs and the stakeholders to whom these accrue.

While this research relates to the operation of these programs in the United States there are reasonable grounds, given the understood pathways on how these outcomes are manifest, for considering that a similar spread of benefits is likely to be present in Australia.

| Timing of monetisable effect | Stakeholders who incur monetisable effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program participants | Tax payers | Rest of society | |||

| Reduced child abuse and neglect | Childhood | + | + | ||

| Improved school readiness | Adulthood | + (i) | + (i) | ||

| Higher achievement tests | Adulthood | + (i) | + (i) | ||

| Reduced special education use | K-12 years | + | |||

| Reduced grade retention | K-12 years | + | |||

| Increased high school graduation | Adulthood | + (i) | + | ||

| Increased higher education attainment | Adulthood | - | - | ||

| Higher earnings and taxes paid | Adulthood | + | + | ||

| Reduced crime | Adolescence to Adulthood | + | + | ||

| Reduced welfare use | Adolescence to Adulthood | - | + | ||

| Improved health and health behaviour | Adolescence to Adulthood | + | + | + | |

Source: Karoly (2017), p. 59.

Notes: + denotes a favourable effect; - denotes an unfavourable effect. (i) indicate monetisable effect is indirect, i.e. through linkages to later outcomes. Examples include depression, smoking, substance abuse, mortality, and teen pregnancy.

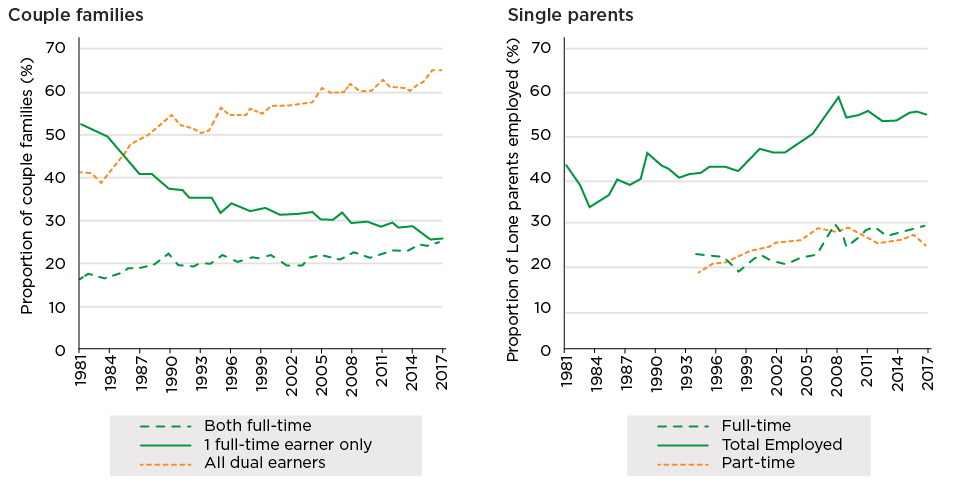

2.5 Trends in parental employment in Australia

Since 1981 the proportion of couple households with dependent children under 15 years of age in which both parents were in paid employment increased from 41.0 per cent to 65.0 per cent in 2017 (Figure 2.1). The proportion in which there was only one full-time earner decreased from 52.4 per cent to 25.9 per cent over this time period. The proportion of households in which both parents were working full-time increased from 16.5 per cent in 1981 to 25.8 per cent in 2017.

The employment rate of single parents also increased substantially over this period; from 43.2 per cent in 1981 to 55.4 per cent in 2017. While there have been some fluctuations since 1994 (when this breakdown started to be published), the growth in employment of lone parents was roughly equally for part-time and full-time employment.

Figure 2.9. Employment of parents in couple and single parent families with dependent children aged under 15 years 1981 to 2017

Source: Derived from ABS 6224.0 (Various)

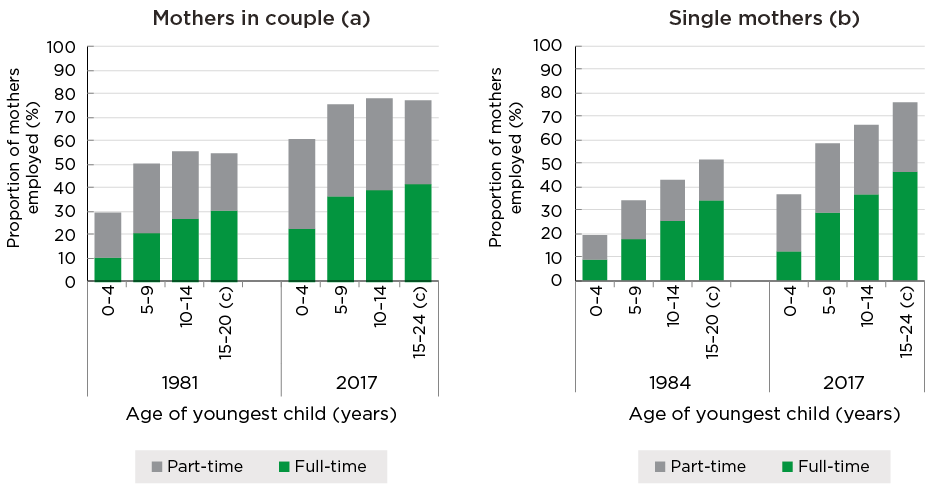

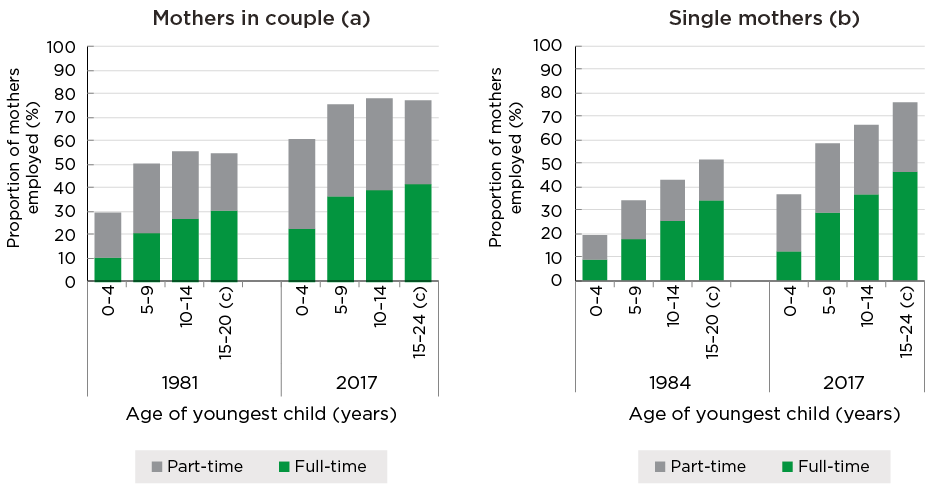

Figure 2.10 shows the employment to population rates for partnered and single mothers with dependent children by the age of their youngest child for 1981 and 2017. There were big increases in employment rates between 1981 and 2017 for all groups irrespective of the age of the youngest child, with the biggest increase for women with a child aged 0 to 4 years whose employment rate increased from 29.6 per cent in 1981 to 60.8 per cent in 2017, a 31.2 percentage point gain. For those with a youngest child aged 5 to 9 years there was a 25.5 percentage point increase in their employment to population rate and for those with children aged 10 to 14 years the employment to population rate increased by 23.0 percentage points. Interestingly there was little change in the share of employment that was full-time between 1981 and 2017 irrespective of the age of the youngest child.

Figure 2.10. Employment to population rate, mothers with dependent children, by age of youngest child and whether they have a partner, 1981, 1984 and 2017

Source: Bray (2018). Underlying data 1981: ABS 6224.0 1981. 2017: ABS 6224.0 2017.

Notes: (a) Opposite sex couples only. (b) Data for single mothers is only available from 1984. (c) In 1981 this category comprised dependent full-time students aged 15-19 years. In 2017 this group included such students aged 15-24 years.

Reasons for using child care

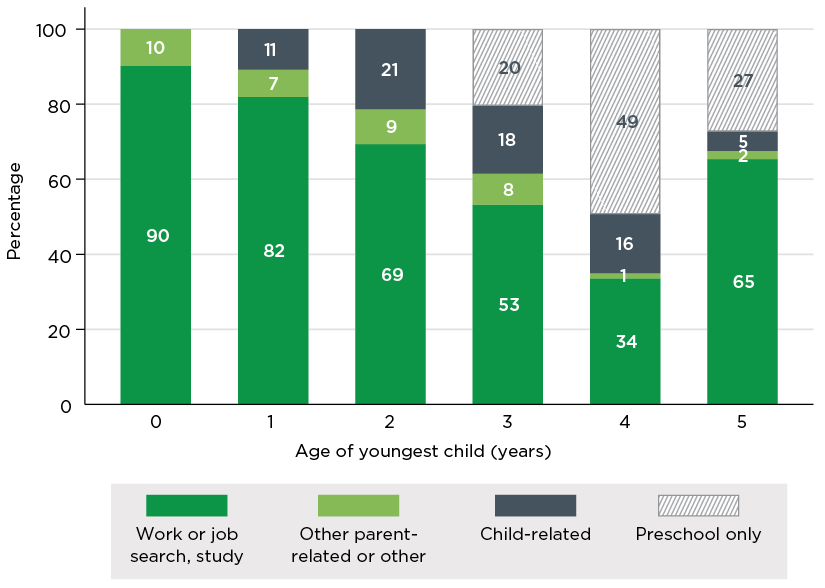

Parents use child care for a range of reasons, including to allow them to be in paid employment and to provide developmental/educational opportunities for their children. A large majority of parents using formal child care give the main reason for their child or children attending care as being because of paid employment, study, training or job search activities.

Data from the 2017 ABS Childhood Education and Care Survey reveal that about three-quarters (76 per cent) of parents with a child under 6 years of age using formal care (other than preschool) report that the main reason for using formal care was because of work, study/training or job search, 14 per cent because they thought it was good for the child, 5 per cent to prepare the child for school and 6 per cent for other parent-related reasons (the most common being to 'give parents a break').

For children aged 6 years or over in formal child care, 92 per cent of parents said that the main reason for using formal care was because of work, study/training or job search; 5 per cent attended due to other parent-related reasons; and just 4 per cent attended for child-related reasons (Figure 2.11). For each age group of children, the category 'parents' work, study/training or job search' is predominantly for parents' work.12

Figure 2.11. Parents' main reasons for using formal child care or preschool, by child age for children under 6 years, 2017

Source: ABS 4402.0 2017. Derived using TableBuilder.

Notes: Columns add to the total percentage of parents using formal child care or early learning. The Childhood Education and Care Survey does not ask about the reasons as to why children are attending preschool.

2.6 Patterns of child care and preschool usage

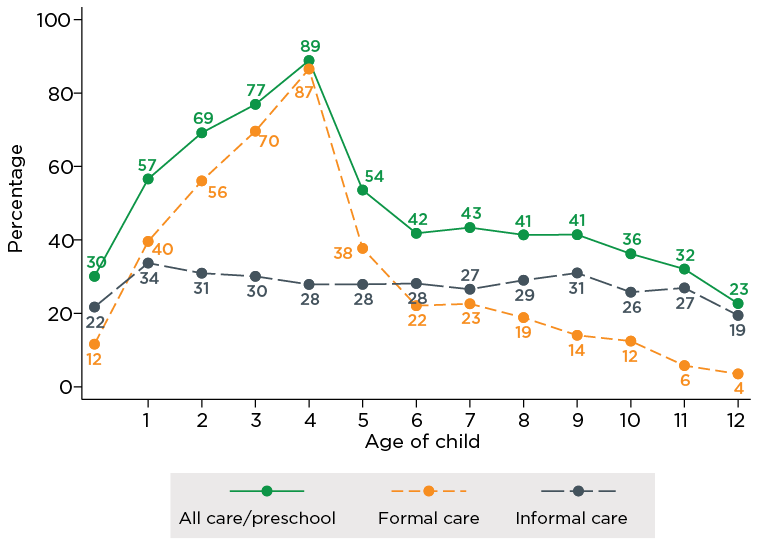

In June 2017 the proportion of children in formal child care or preschool was 12 per cent of children under the age of 1 year, 40 per cent of children aged 1, 56 per cent of children aged 2, 70 per cent of children aged 3 and reaches a peak of 87 per cent of children aged 4 years (Figure 2.12). It then falls with age of the child to be 38 per cent of children aged 5 years and just 6 per cent of children aged 11 years.

Figure 2.12. Children's participation in child care or preschool by age of child (years), 2017

Source: ABS 4402.0 2017. Derived using TableBuilder.

Notes: Formal care includes Long Day Care, Family Day Care, Outside School Hours Care, Occasional Care or other registered care. These estimates are for care used in the preceding week.

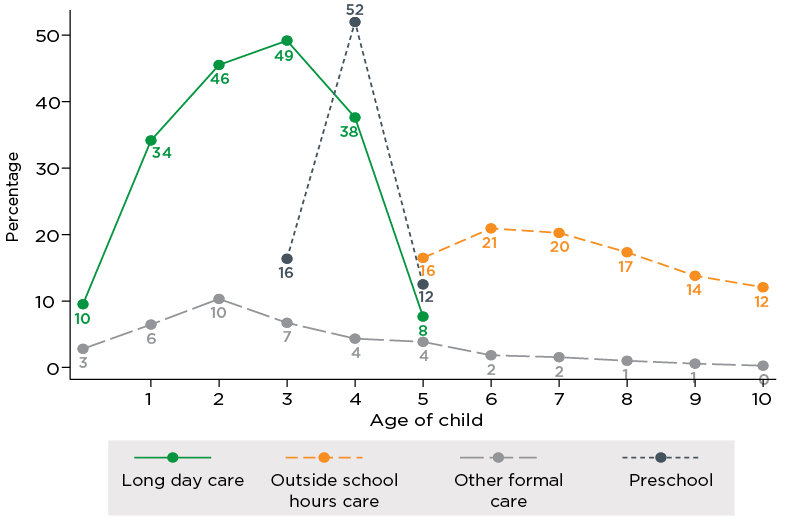

The age-related patterns of formal care participation reflect patterns of participation in different types of formal care and early learning (Figure 2.13):

- Preschool is available to children in the year or two before they commence full-time school, so participation clearly peaked at 4 years, with some 3 year olds and 5 year olds also participating in preschool.

- Long Day Care was the main source of formal care to children under school age, with the highest proportions of children in Long Day Care being 2-3 years (46-49 per cent of children), but with 34 per cent of 1 year olds and 38 per cent of 4 year olds also in Long Day Care.

- Smaller percentages of under-school-aged children were in other forms of formal care, which includes Family Day Care and Occasional Care.

- The main provision of formal care to school-aged children was as Outside School Hours Care, and the percentage for this form of care was highest for 6 year olds at 21 per cent, with proportions declining with age of child beyond this.

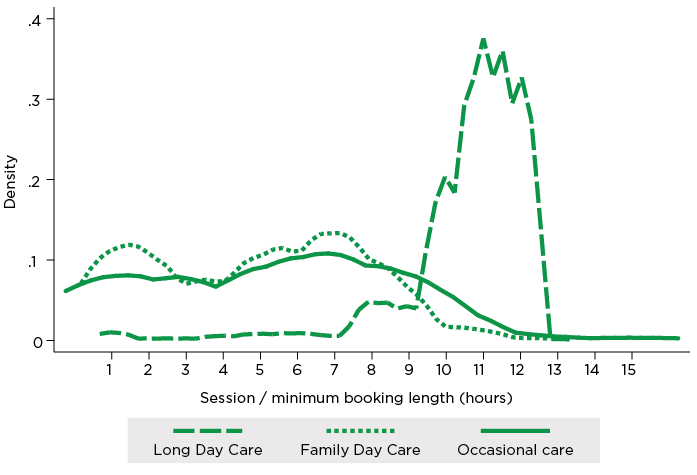

The average weekly hours in child care in December 2017 was 24.6 hours. It varied from 28.8 hours per week for Long Day Care and 28.5 hours per week for Family Day Care and In Home Care, to 12.2 hours for Occasional Care and 11.2 hours for Outside School Hours Care (Department of Education and Training, 2018c).

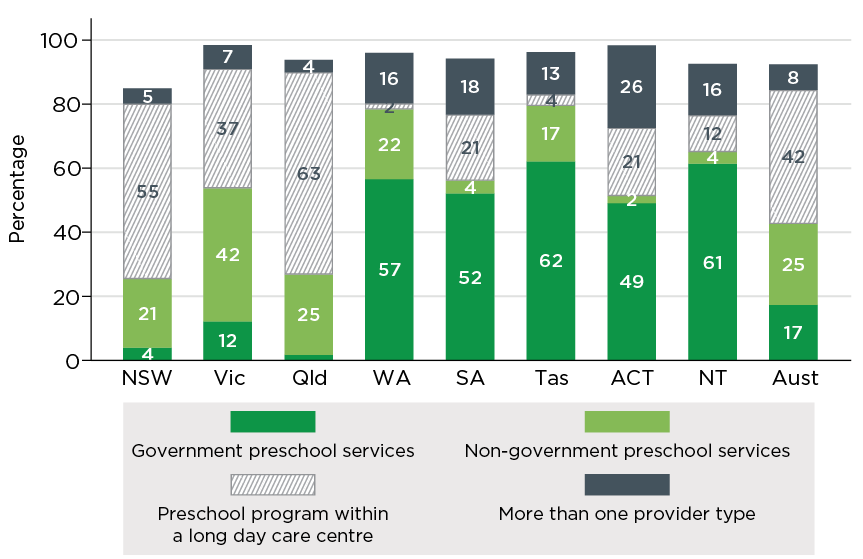

Figure 2.13 reports the proportion of children in preschool and Long Day Care separately. However, some Long Day Care centres provide a preschool program, and there is considerable variation in the way in which preschool is delivered across jurisdictions. In some jurisdictions, early childhood education is primarily delivered through dedicated preschools or kindergartens, often attached to schools. In others, it is more often delivered through the child care system. See Baxter and Hand (2013) for more information. Detailed information produced by the ABS on the service types of children aged 4 to 5 years attending preschool programs is shown in Figure 2.14, showing clear variation across jurisdictions.

Figure 2.13. Types of formal child care and early learning by child age (years), 2017

Source: ABS 4402.0 2017. Derived using TableBuilder.

Notes: Information for 11 and 12 year olds is not shown because of the high standard error on the estimate. Small estimates for 'Other formal' are also excluded for school-aged children. 'Other formal' includes Family Day Care and Occasional care. These estimates are for care used in the preceding week.

Figure 2.14. Service types of children aged 4 and 5 years attending preschool programs, by state/territory, 2016

Source: ABS, 4240.0 2016 (Table 3).

Notes: The ABS defines 'preschool program' for the purposes of this collection as 'a structured, play based learning program, delivered by a degree qualified teacher, aimed primarily at children in the year or two before they commence full-time schooling. This is irrespective of the type of institution that provides it or whether it is government funded or privately provided.' The ABS notes that care should be taken when comparing jurisdictions. On the table sourcing these data, they note there may be some duplication of children across service types in the Queensland estimates.

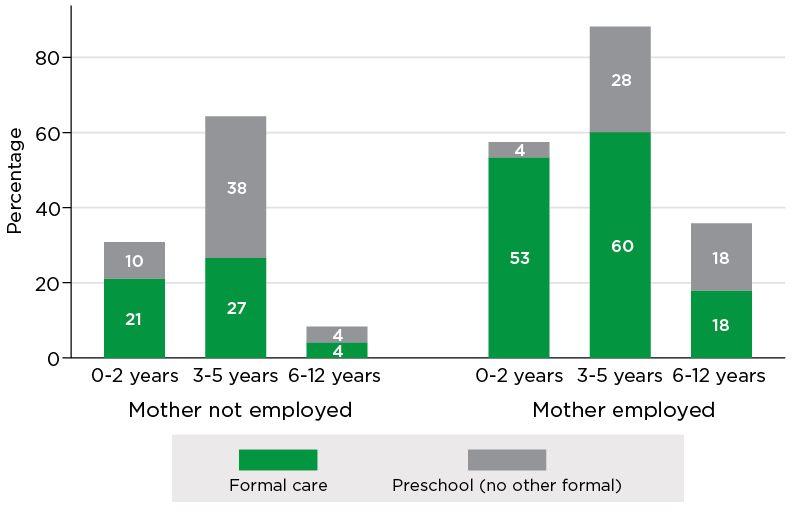

Families not using child care

The proportion of children not in formal care is much lower for families in which the mother is employed and is a little lower for children aged 3 to 5 years than children aged under 3 years (Figure 2.15). This pattern is consistent with parents' reports on the main reason for using child care being for parental employment.

Figure 2.15. Family use of child care, age of youngest child and mothers' work status

Source: ABS 4402.0 2017. Derived using TableBuilder

Note: Formal care used by any children in the family

Parents in the Baseline Parent Survey who had not used child care in the past year were asked why they had not used child care. Overwhelmingly, as shown in Figure 2.16, the most common response was parents agreeing that they preferred to take care of their child themselves (or have their partner take care of their children) - 78 per cent of parents. This was the most common response, regardless of age of youngest child and of mothers' employment status. The second most common response was the cost of child care reported by 57 per cent of families with employed mothers and 65 per cent of families where the mother was not employed.

Figure 2.16. Families not using child care: Reasons care not used by mothers' work status

Source: Baseline Parent Survey, May 2018.

Notes: Percentages calculated over those who answered one of 'Agree', 'Neither agree or disagree' or 'Disagree', with those who answered 'Not applicable' excluded. This is the percentage who answered 'agree'.

2.7 Overview of the child care system prior to July 2018

Child care payments

This section provides an overview of the child care system as of March 2018, immediately prior to the introduction of the new Child Care Package. Under this prior arrangement support for parents with the cost of child care was primarily through a combination of the Child Care Benefit and Child Care Rebate. Both payments were provided on a per child basis. Additional support for some families was available through Jobs, Education and Training Child Care Fee Assistance, Grandparent Child Care Benefit and Special Child Care Benefit.

The Child Care Benefit was a means tested benefit covering up to 50 hours of approved child care use per child per week provided that parents satisfied an activity test of at least 15 hours per week. 13 The rate of Child Care Benefit depended upon the number of hours of work-related activities, the number of hours of child care used, the number of children in child care, whether the children were at or below school age, the type of service attended, and family income. Families that did not meet the activity test were eligible for Child Care Benefit for up to 24 hours of child care per child per week. Child Care Benefit could be paid either direct to child care services to reduce the fees charged (fee reductions were based on estimated financial year income with reconciliations at the end of the financial year) or as a lump sum payment to parents after reconciliation at the end of the financial year.

The maximum rate of Child Care Benefit was $4.30 per hour for a non-school child ($215 for a 50-hour week). Rates for school children were 85 per cent of the non-school child rate. The maximum rate of Child Care Benefit was payable for families with an income under $45,114 or families on income support. Families with an income above specified income limits did not receive Child Care Benefit with the limit being $156,914 for a family with one child in care, $162,633 for a family with two children in care and $183,655 for a family with three or more children in care and $34,724 for each subsequent child.

The Child Care Rebate was a non-means tested payment that provided additional assistance for families using approved child care. Child Care Rebate provided up to 50 per cent of a family's out-of-pocket child care expenses (after Child Care Benefit was deducted) to a maximum of $7,613 per child per year. To be eligible for the rebate, parents were required to have had some work, training or study related commitments during the week, although there was no minimum number of hours of such activity required.

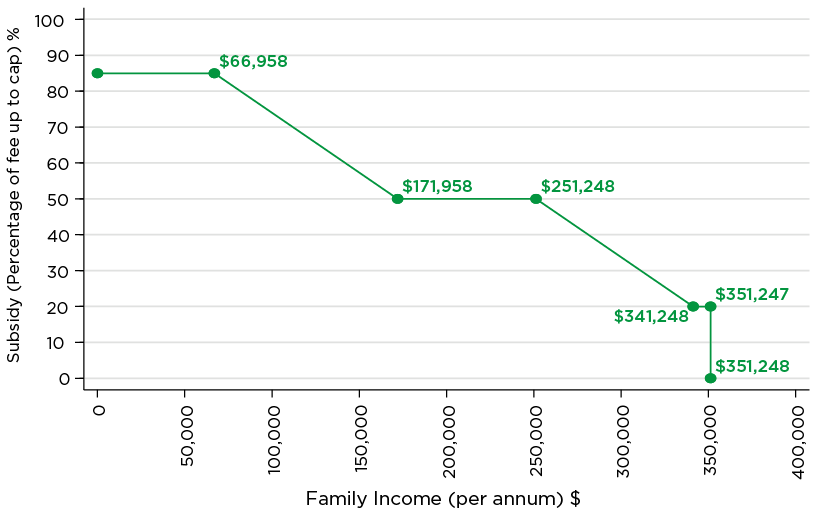

Using policy settings as at June 2018, Figure 2.17 shows how the amount of Child Care Benefit, Child Care Rebate and the cost paid by parents varied with family income. The scenario is for a family with a preschool-aged child using 40 hours of care per week with child care fees of $500 per week.

Figure 2.17. Child Care Benefit, Child Care Rebate and cost paid by parents by family income, June 2018

Source: Derived from Child Care Benefit and Child Care Rebate Program parameters.

Note: For one preschool child using 40 hours of standard Long Day Care per week and child care fees of $500 per week.

The Jobs, Education and Training Child Care Fee Assistance provided financial assistance to eligible parents who qualified for the maximum rate of Child Care Benefit and it paid for most of the gap in out-of-pocket costs while a parent was working, studying or training.

Special Child Care Benefit was available for families experiencing financial hardship or for children at risk. Grandparents who were primary carers of a child may have been eligible for Grandparent Child Care Benefit. Special and Grandparent Child Care Benefit could be up to the full costs of child care and were not subject to an activity test.

Child care programs

In addition to the general support provided to parents, a range of programs existed primarily to support services, or in some cases specific groups of parents. The Community Support Program provided assistance payments to providers including establishment and sustainability assistance, operational support, Long Day Care Capital Funding Exceptional Circumstances Grants and the Regional Travel Assistance Grants. The Community Support Program ceased in June 2018, with the introduction of the Community Child Care Fund in July 2018.

The Budget Based Funded (BBF) Program (established in 2003) had similar objectives to the Community Support Program, but with an emphasis on non-mainstream services in rural, remote and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Non-mainstream services were established to provide child care where the market would otherwise fail to provide services.

The In Home Care program provided a flexible form of child care to children in the child's home. It was only available to children in specific circumstances, including where the child or other children in the home had a disability, the parent or their partner had a disability that reduced their capacity to care for the child, the child lived in a rural or remote area, and/or the work hours of the child's parents meant that no other services were available.

The Inclusion Support Programme is part of the Child Care Package, but was introduced in 2016 following the cessation of the former Inclusion and Professional Support Program. It provides support to child care services to enable them to provide inclusive approaches to the provision of child care. This support may include access to the Inclusion Development Fund.

Connected Beginnings is similarly part of the Child Care Package but has also operated since July 2016. It provides support to integrate early childhood, maternal and child health and family support services with schools in a selected number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

2.8 Summary

There has been strong growth in the child care sector over the last 40 years as a result of increases in parental employment (particularly couples in which both parents are in paid employment) and population growth. The primary focus of the child care sector is about enabling parental employment, although the focus on the child developmental and educational outcomes has increased via the development, implementation and enforcement of national quality standards.

The mix of types of child care has changed over time, but both Long Day Care and Family Day Care remain significant. For school-aged children there has been a rapid increase in Outside School Hours Care and this is a growing sector. A substantial proportion of child care, particularly in the Family Day Care and Long Day Care sectors is provided by the private sector and this appears to have been relatively stable since the mid-1990s.

The underlying cost of provision of child care has grown much more rapidly than prices overall. This reflects many factors including changes in quality and the costs of staffing. ABS estimates indicate that while government policies directed at this have had some immediate success in offsetting the more rapid increase in the cost of child care, they have not been successful at addressing the overall trend over time.

2 This chapter is based on a forthcoming publication by Bray, Hand, Baxter and Gray.

3 Most references to this form of care in this report refer instead to Long Day Care as the care type, as the use of 'Centre Based Day Care' replaced Long Day Care as a care type on 2 July 2018.

4 The early learning programs in the year before full-time school (and in some states, two years before) are generally referred to as preschool or kindergarten, but with the actual terminology varying across states. For the purposes of this report, we have generally used the terminology of preschool.