Mental health of Australian males: depression, suicidality and loneliness

Ten to Men Insights #1: Chapter 1

September 2020

Overview

AIFS recognises that each of the numbers reported here represents an individual. AIFS acknowledges the devastating effects suicide and self-harm can have on people, their families, friends and communities.

This chapter discusses suicide and presents material that some people may find distressing. If you or someone you know is feeling depressed or suicidal, please contact one of the following services:

- In an emergency, call 000

- Lifeline

ph. 13 11 14 - Kids Help Line (5-25 years)

ph. 1800 55 1800 - MensLine Australia

ph. 1300 789 978

Mental ill-health is common among Australians; about one in five experience some type of mental health concern during any given year (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2007). Mental illness tends to develop early in life, with three-quarters of those who have mental ill-health first experiencing symptoms before the age of 25 years (Kessler et al., 2007). Mental health difficulties present a range of challenges and are often associated with adverse outcomes including reduced quality of life (Evans, Banerjee, Leese, & Huxley, 2007) and changes in socio-economic participation (Doran & Kinchin, 2019).

Among males, the personal, societal and economic costs of unaddressed mental ill-health are significant. Estimates suggest that the annual costs for severe mental illness among Australians are over $50 billion, which include the direct costs of mental health care and other services as well as the indirect costs due to loss of productivity (Cook, 2019). From 15 to 24 years of age, the leading causes of disease burden in males are suicide and self-inflicted injuries, and alcohol use disorders. Between 25 and 44 years of age, suicide and self-inflicted injuries continue to be the leading cause of disease burden (and fatal burden) for males (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2019a).

Recent statistics show that suicide continues to be more common among Australian men than women (ABS, 2019), with men making up more than three-quarters of suicidal deaths. On average, there are six male suicides every day. Research has also indicated that the risk of suicide increases over time for men (AIHW, 2016, 2019a), with the highest rates of suicide among those aged 30-59 years.

This chapter focuses on the mental health of men of different ages, followed by who they seek help from for their mental health concerns. Using data from the two current waves of Ten to Men (TTM), this chapter explores the mental health disease burden, symptoms and severity of depression among males of all ages, prevalence and patterns of escalation in suicide, and how loneliness may affect these experiences. Health care use for those with past year depression, anxiety and suicidality is also explored. Analyses aim to include boys where possible, but generally the focus throughout the chapter is on young men and adults.

Key messages

-

Mental health concerns among men:

- Mental ill-health remains high among Australian men, with up to 25% experiencing a diagnosed mental health disorder in their lifetime, and 15% experiencing a disorder in a 12-month period.

- Anxiety was the most common mental health disorder among boys (9%).

- Depression was the most common mental health disorder among young men and adults, steadily increasing in prevalence from age 15-17 (7%) to old age (13%).

- A significant proportion of men who experienced depression at a given point in time continued to experience it or relapsed. Of those with self-reported severe depression in 2013/14, 40% still reported experiencing severe depressive symptoms in 2015/16.

- Young men were the most likely to experience suicidal escalation from 2013/14 to 2015/16, with just under 3% of young men escalating to make a first suicide attempt in that time.

- Around 4% of Australian men reported that they are lonely (i.e. have no close friend).

- Loneliness was significantly associated with experiences of depression and suicidality among Australian men, above and beyond area-level socio-economic disadvantage and unemployment.

-

Health service use among men:

- Only a quarter of men said they would be likely or very likely to seek help from a mental health professional if they experienced an emotional or personal problem. Almost 25% said they would not seek help from anyone.

- Adult men said they would be least likely to seek help from a phone helpline, with around 80% indicating they would be very unlikely or unlikely to seek help from this source.

- Many Australian males were not accessing professional support. While over 80% of men with depression, anxiety and/or any suicidality in the past year had seen a General Practitioner (GP), only around 40% had seen a mental health professional.

Diagnosed mental health disorders

Psychiatric disorders range from mood disorders, such as depression, through to substance use disorders. Around a quarter of Australian males experience at least one of these disorders in their lifetime, with the most common being depression, followed by anxiety (Williams et al., 2015).

Experience of lifetime and past year mental health disorders

In 2013/14, TTM respondents were asked about a range of mental health conditions they had been diagnosed with in their lifetime or experienced in the past 12 months (Box 1.1).

Box 1.1: Diagnosed mental health disorders

Ten to Men young men (15-17 years old) and adult men (18-57 years old) were asked:

- whether they had ever been diagnosed with each condition in the past ('Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you had this condition?')

- whether they had experienced recent (past year) symptoms or associated treatment ('Have you been treated for or had any symptoms of this condition in the past 12 months?').

Parents of boys (10-14 years old) were also asked to report diagnosed mental health disorders on behalf of their sons.

The list of mental health conditions included:

- for adult males: depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- for young men and boys: depression, anxiety, eating disorders, substance abuse and conduct disorder.

Population estimates were calculated for each age group. This represents the approximate number of males in that age group in Australia who would have been suffering from that condition at the time of measurement.

Among adults in the TTM sample, the lifetime prevalence of any mental health disorder was high, although somewhat lower than other population estimates (Table 1.1).1 This is likely due to TTM participants not being asked about their experience of all mental health disorders. Nevertheless, findings indicate that, in 2013/14, just under one-quarter of adult men had experienced one of the included disorders in their lifetime. Depression and anxiety were the most commonly reported diagnosed mental health disorders for all age groups.

While depression was the most common disorder (lifetime and 12-month prevalence) among both adult men (20% and 13%, respectively) and young men (11% and 7%, respectively), anxiety was the most common among boys (9% and 6%, respectively). Population estimates are included in Table 1.1 to indicate roughly how many individuals were likely affected in the population, based on the population size at that time. For example, it is estimated that in 2013/14, almost 700,000 Australian adult men experienced symptoms or were treated for depression in the past year.

Table 1.1: Estimated prevalence of mental health disorders (lifetime and past year) among Australian males in 2013/14

| Lifetime | 12-months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Population estimate | % | Population estimate | |

| Boys (n = 1,099) | Population size = 685,424 | |||

| Any disorder | 11.2 | 76,630 | 7.9 | 54,217 |

| Mood disorders: Depression | 4.9 | 33,517 | 4.0 | 27,074 |

| Anxiety disorders: General anxiety disorder | 9.1 | 62,236 | 6.3 | 43,045 |

Disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders | ||||

| Conduct disorder | 0 | - | 0 | - |

| Young men (n = 1,024) | Population size = 425,936 | |||

| Any disorder | 14.1 | 60,185 | 9.6 | 40,720 |

| Mood disorders: Depression | 10.9 | 46,299 | 7.4 | 31,562 |

| Anxiety disorders: General anxiety disorder | 9.1 | 38,803 | 5.8 | 24,704 |

| Eating disorders | 1.3 | 5,367 | 0.7 | 3,024 |

| Substance abuse disorders | 1.3 | 5,495 | 0 | - |

Disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders | ||||

| Conduct disorder | 1.1 | 4,558 | 0 | - |

| Adults (n = 13,891) | Population size = 5,424,422 | |||

| Any disorder | 23.5 | 1,272,569 | 15.1 | 820,173 |

| Mood disorders: Depression | 19.7 | 1,065,899 | 12.8 | 693,241 |

| Anxiety disorders: General anxiety disorder | 12.1 | 654,728 | 8.0 | 435,581 |

| Trauma-related disorders: Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | 3.2 | 175,209 | 1.9 | 103,606 |

| Psychotic disorders: Schizophrenia | 0.8 | 45,023 | 0.6 | 30,377 |

Note: 'Any disorder' was calculated based on whether the respondent had said 'yes' to any of the disorders that they were asked about.

Source: TTM data, Wave 1, all cohorts, weighted

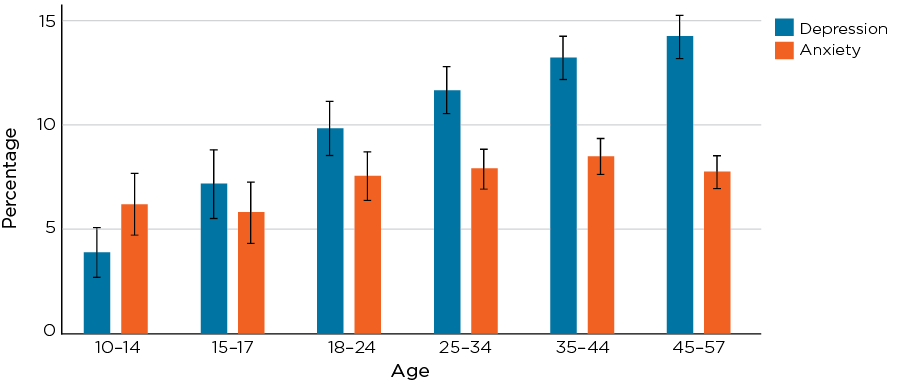

The prevalence of the most common disorders (depression and anxiety) varied substantially by age (Figure 1.1). Experiences of depression steadily increased with age, ranging from 7% of 15-17 year olds to just under 15% of men aged 45 and over. In comparison, the prevalence of anxiety did not vary much by age, ranging from 6% of those aged 15-17 to around 8% of men aged 18 and over.

Figure 1.1: Estimated prevalence of past year anxiety and depression among Australian males aged 10-57 in 2013/14

Note: n = 1,030 at age 10-14; 963 at age 15-17; 1,966 for ages 18-24; 3,058 for ages 25-34; 4,080 for ages 35-44; and 4,475 for ages 45 and over. Brackets above/below bars represent 95% Confidence Intervals.

Source: TTM data, Wave 1, all cohorts, weighted

Credit: Ten to Men 2020

Socio-demographic factors linked to anxiety and depression

Previous research has pointed to several socio-demographic factors associated with an increased risk of experiencing poor mental health. These factors include disadvantage, lower education, unemployment and ethnic minority status (Bailey, Mokonogho, & Kumar, 2019; Lorant et al., 2003). Identifying as non-heterosexual has also been linked with an increased risk for depression (Scott, Lasiuk, & Norris, 2016).

In the TTM sample, after accounting for all these socio-demographic factors, age, non-heterosexuality, being from a culturally and linguistically diverse background (CALD), higher education, unemployment, marital status and higher area-level disadvantage all significantly affected the likelihood of experiencing depression and anxiety (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2: Socio-demographic characteristics associated with past year depression and anxiety among adult men in 2013/14

| Depression | Anxiety | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | SE | aOR | SE | |

| Age | 1.02*** | <-0.01 | 1.01* | <0.01 |

| Non-heterosexuality | 1.54*** | -0.16 | 1.26* | 0.16 |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | 1.37* | -0.22 | 0.94 | 0.20 |

| CALD background | 0.25*** | -0.04 | 0.28*** | 0.06 |

| Highest level of education achieved (ref. = completed Year 12) | ||||

| <Year 12 | 1.00 | -0.08 | 1.04 | 0.10 |

| Certificate/diploma | 1.10 | -0.08 | 1.09 | 0.10 |

| University degree | 1.79*** | -0.28 | 1.80*** | 0.33 |

| Employment status (ref. = employed) | ||||

| Unemployed, looking for work | 2.64*** | -0.23 | 2.31*** | 0.24 |

| Out of labour force | 4.28*** | -0.38 | 4.33*** | 0.42 |

| Marital status (ref. = single) | ||||

| Widowed | 1.22 | -0.52 | 1.95 | 0.85 |

| Divorced | 1.49*** | -0.20 | 1.44** | 0.23 |

| Separated but not divorced | 2.48*** | -0.36 | 1.23 | 0.24 |

| Married/de facto | 0.82** | -0.06 | 0.81** | 0.08 |

| SEIFA (ref. = low disadvantage) | ||||

| High disadvantage | 1.47*** | -0.12 | 1.55*** | 0.16 |

| Middle disadvantage | 1.21** | -0.09 | 1.39*** | 0.13 |

| ASGS (ref. = inner city) | ||||

| Inner regional areas | 1.08 | -0.07 | 0.99 | 0.08 |

| Outer regional areas | 0.88* | -0.07 | 0.88 | 0.08 |

| Total, n | 12,577 | 12,539 | ||

Notes: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10. SEIFA = Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas; ASGS = Australian Statistical Geography Standard; CALD = Culturally and Linguistically Diverse; (ref.) is the reference category to which the other categories are compared. aOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio. SE = standard errors.

Source: TTM data, Wave 1, adult cohort

Among adult men, being out of the labour force was associated with the greatest risk for depression; those who were out of the labour force were four times more likely to have depression compared to those who were employed. Being unemployed, identifying as non-heterosexual and experiencing high area-level disadvantage were also associated with a significantly higher risk of having depression.

Being from a CALD background was associated with a lower likelihood of having depression. Being married/living in a de facto relationship was also associated with a reduced risk for experiencing depression, while being divorced or separated was associated with a 1.5 and 2.5 times increased risk for depression, respectively. This suggests being in a relationship has a protective role against depression for males. This is consistent with literature that indicates that men, in particular, experience mental health benefits from being in a relationship (Amato, 2014; Bulloch, Williams, Lavorato, & Patten, 2017).

Similar results were found for anxiety among adult men. Being unemployed or out of the labour force were associated with increased likelihood of experiencing anxiety, and this effect was greater for being out of the labor force than unemployed but looking for work. Adult men of CALD backgrounds were less likely to experience anxiety. Education and regional location were not significantly associated with anxiety, except for having a university degree, which was associated with an almost two-fold increase in the likelihood of experiencing anxiety.

Findings, therefore, indicate that rates of depression and anxiety are high among Australian males, and support previous evidence that males with specific socio-demographics are at greater risk of experiencing these disorders. In particular, being unemployed and living in a more highly disadvantaged area are common experiences among men who report depression and anxiety. Identifying as non-heterosexual is associated with increased risk for depression but not necessarily anxiety.

Experience of two or more mental health disorders

Many who experience one mental health disorder also experience symptoms of one or more other disorders at the same time (termed 'comorbidity'). Here, comorbidity is defined as having experienced two or more of the included disorders in the past 12-month period. It is important to consider the cumulative burden comorbid disorders can have. Research indicates that lifetime comorbidity for some disorders is as high as over 90% (Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Walters, & Jin, 2005; Krueger, Chentsova-Dutton, Markon, Goldberg, & Ormel, 2003). Having more than one disorder at the same time significantly increases the personal and public health costs, as it becomes much more difficult to effectively diagnose and treat disorders that may share underlying symptoms.

In 2013/14, around 15% of TTM adult respondents had experienced at least one mental health disorder in the last 12 months. Comorbidity was also proportionally high, with almost 7% of all TTM adult men having experienced at least two mental health disorders in the past 12 months (Table 1.3). Out of those who experienced any mental health disorder, 57% experienced only one disorder, around 36% experienced two disorders, and 7% experienced three or more in the past year. The most commonly co-occurring disorders were depression and anxiety. Almost 90% of adult men who had any comorbidity reported experiencing both depression and anxiety in the past 12 months. This is equivalent to roughly 6% of all Australian men (or 309,124 men) in 2013/14. Around one-quarter of those with comorbidity experienced both PTSD and depression.

Past year experiences of comorbid mental health disorders appear to be common among adult men, and the associated burden would be high. Given how common depression is among adult men, this is explored in greater depth to look not just at the past year diagnosed disorder but also to examine symptom severity and potential changes (improvement and worsening) over time.

Table 1.3: Comorbidity among adult males with at least one mental health disorder in past 12 months in 2013/14

| Prevalence of comorbidity 12-months % | |

|---|---|

| Number of disorders among all adult males | |

| Any disorder (at least one) | 15.1 |

| Any comorbidity (2+ disorders) | 6.5 |

| Total, n | 13,894 |

| Number of disorders among adult males with at least one disorder | |

| 1 | 57.0 |

| 2 | 36.0 |

| 3+ | 7.1 |

| Total, n | 2,155 |

| Most common comorbid disorders among adult males with at least two disorders | |

| Depression and anxiety | 88.4 |

| PTSD and depression | 22.9 |

| Total, n | 929 |

Notes: Comorbidity is only evaluated for those disorders that had been assessed and is likely an underestimation. Types of comorbidity (e.g. depression and anxiety, PTSD and depression) were not mutually exclusive; so it is possible that there are some cases who had depression, anxiety and PTSD, or comorbidity of a different set of psychiatric disorders. Because n's for those comorbidities were much smaller, they were not reported.

Source: TTM data, Wave 1, adult cohort, weighted

1 Previous population estimates rely on national health and mental health surveys conducted by the ABS and AIHW. More information can be found in the following resources: AIHW. (2019). The health of Australia's males. Retrieved from www.aihw.gov.au/reports/men-women/male-health. ABS. (2018). National Health Survey: First results 2017-18. (ABS cat. no. 4364.0.55.001). Canberra: ABS.

Depression: severity, symptoms, persistence

To be diagnosed with depression, a person needs to be experiencing symptoms for at least two weeks (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), and symptoms need to be experienced at least half of the time. Individual symptoms and symptom severity were examined among TTM respondents using a self-report questionnaire that assessed depressive symptoms experienced in the last two weeks, and how often (Box 1.2).

Box 1.2: Measuring symptoms of depression

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) was used to assess depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. The questionnaire included nine items with responses on a four-point scale where 0 meant 'not at all', 1 'several days', 2 'more than half of days' and 3 'nearly every day'. These were summed to create the PHQ score, which ranged from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating a greater level of depression severity. The scores were then divided into four categories:

| Score | Depression severity | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Probable major depressive disorder | ||

| 0-4 | Minimal or none | Monitor |

| 5-9 | Mild | Clinical judgement to determine necessity of further assessment and/or treatment |

| 10-14 | Moderate | |

| 15-27 | Moderately severe | Warrants active treatment |

| 10+ | Probable MDD | Needs at least 5 out of all 9 symptoms experienced more than half the days in the past two weeks (must include either depressed mood or anhedonia (i.e. inability to feel pleasure)) |

In the past two weeks, adult men were most likely to experience probable major depression (7%), with around 5% of all men experiencing severe symptoms (Table 1.4). Around a fifth of boys, young men and adults experienced mild symptoms. Compared to other general population estimates that examined depressive severity (e.g. Germany: Hinz et al., 2016; Kocalevent, Hinz, & Brähler, 2013), a greater proportion of TTM adult males experienced mild, moderate and severe depressive symptoms in the past two weeks.

Table 1.4: Depression severity in the past two weeks among males by age group in 2013/14

| Boys % | Young men % | Adults % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression severity | |||

| None | 69.4 | 62.9 | 63.2 |

| Mild | 21.5 | 23.8 | 23.7 |

| Moderate | 7.9 | 9.4 | 7.6 |

| Severe | 1.2 | 3.9 | 5.5 |

| Total, % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Probable major depressive disorder | |||

| Score 10+ | 2.2 | 5.8 | 6.9 |

| Total, n | 1,066 | 1,004 | 13,573 |

Source: TTM data, Wave 1, all cohorts, weighted

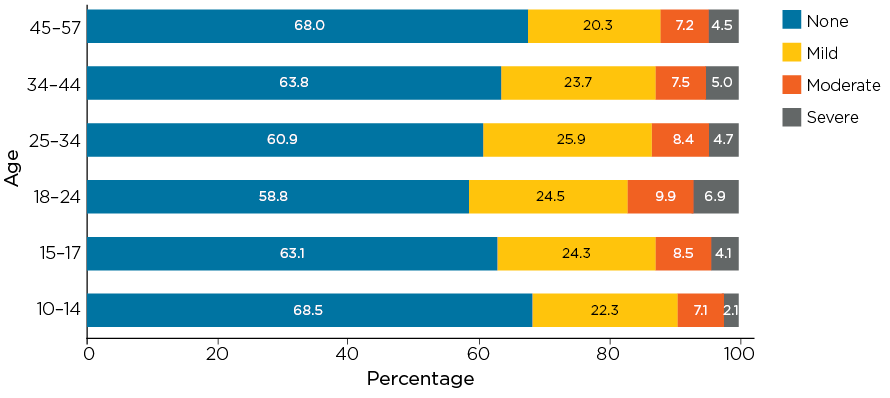

To explore depression severity across ages in greater depth, symptom severity was mapped by age groups with adults separated into four age categories. This showed that severity among adults varied across life stages (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Depressive symptom severity by age groups in 2013/14

Notes: N = 15,414, broken down by age group: n = 1,030 at age 10-14; 963 at age 15-17; 1,966 for ages 18-24; 3,058 for ages 25-34; 4,080 for ages 35-44; and 4,475 for ages 45 and over.

Source: TTM data, Wave 1, all cohorts, weighted

Credit: Ten to Men 2020

The highest proportion of those experiencing moderate or severe symptoms of depression was among males aged 18-24 years, further indicating that this group is particularly vulnerable. Over 40% of young men in this age bracket experienced at least mild symptoms of depression.

As the experience of depression is not homogenous (i.e. different people experience different combinations of symptoms), it is important to consider symptom patterns in addition to overall severity. This helps to enhance understanding of how certain symptoms of depression may be more commonly experienced in some age groups, which can inform identification and prevention efforts.

The most commonly reported depressive symptoms among Australian males in 2013/14 differed slightly by age (Table 1.5). Boys reported that at least half of the time they have experienced trouble with sleep (18.5%). Similarly, young men reported trouble with sleep as the most common symptom (20.6%), followed by poor appetite or overeating (18.2%). Among adults, the most commonly reported symptom was feeling tired or having little energy (20%), closely followed by trouble with sleep (18.3%).

Table 1.5: Depressive symptoms among boys, young men and adults in the past two weeks in 2013/14

| Depressive symptoms | % who said 'more than half of days' | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Young Men | Adults | |

| Feeling depressed/down/hopeless (irritable)a | 4.4 | 11.8 | 9.6 |

| Little interest or pleasure doing things | 13.0 | 8.0 | 10.8 |

| Trouble with sleep | 18.5 | 20.6 | 18.3 |

| Tired or little energy | 12.7 | 9.2 | 20.0 |

| Poor appetite or overeating (weight loss)a | 6.6 | 18.2 | 13.6 |

| Feeling bad about self | 4.6 | 12.6 | 10.8 |

| Trouble with concentration | 14.4 | 16.9 | 7.2 |

| Moving or speaking slowly, or fidgety and restless | 6.1 | 5.2 | 3.9 |

| Thoughts better off dead or hurting yourself | 1.3 | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| Total, n | 1,091 | 1,004 | 13,602 |

Notes: a Item wording differed slightly by age group questionnaires; differences are included in parentheses.

Source: TTM data, Wave 1, all cohorts, weighted

Most who experience some or mild symptoms usually start to get better on their own; however, some continue to feel poorly over time or even get worse (Richards, 2011). Changes in depression severity over time were explored from 2013/14 to 2015/16 to identify how many men continued to experience depression over longer periods of time, or potentially relapsed in a two-year period.

Changes in the severity of depression over time

While the majority of those who were categorised as having no depression in 2013/14 still were not experiencing depression in 2015/16, more movement was observed in the mild, moderate and severe categories (Table 1.6). Less than 5% of those with mild depression in 2013/14 progressed to severe depression, though 10% moved to moderate depression. Importantly, over one-third of those who experienced severe depression in 2013/14 were still experiencing severe depression in 2015/16.

Overall, these results indicate that those who experience no or only mild depression continue to experience only low-level symptoms two years later. However, the majority of those who experience severe depression also continue to do so over time, highlighting the need for further treatment/intervention to reduce the likelihood of chronic or recurrent depression among males.

Table 1.6: Transitions in depression severity among all males between 2013/14 and 2015/16

| Transitions in depression severity Depressive symptoms 2015/16 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | ||

| % | % | % | % | n | % | |

| Depressive symptoms 2013/14 | ||||||

| None | 81.3 | 14.1 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 7,389 | 100.0 |

| Mild | 43.3 | 41.2 | 11.1 | 4.4 | 2,598 | 100.0 |

| Moderate | 26.6 | 35.2 | 26.3 | 11.9 | 853 | 100.0 |

| Severe | 12.3 | 25.6 | 26.0 | 36.1 | 498 | 100.0 |

| Total | 65.0 | 22.5 | 7.7 | 4.7 | 11,338 | 100.0 |

Note: N = 11,338.

Source: TTM data, Waves 1 and 2, all cohorts, weighted

Although there were some changes in the severity of depressive symptoms among males (e.g. from mild to moderate or from severe to moderate) not all changes were considered clinically meaningful; that is, indicating improvement or worsening in the individual's health and wellbeing (Box 1.3). Among TTM males, the majority did not have clinically meaningful change in the severity of depressive symptoms over two years (Table 1.7). Around 80% of boys and adult males and 72% of young adults experienced less than five points change or no change in symptom severity over time. Across different ages, around 10% of males experienced clinically meaningful improvement.

Box 1.3: Clinically meaningful change in depressive symptoms

Clinically meaningful change refers to an observable change in depressive symptoms that indicates an improvement or worsening in the individual's health and wellbeing (Dvir, 2015). Positive scores indicate an increase and negative scores indicate a decrease in symptoms. On the PHQ-9, a change of five points or more is considered clinically meaningful change (Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, & Lowe, 2010):

- a reduction in overall symptoms by five points or more is an improvement

- an increase in symptoms by five points or more is worsening.

For each TTM respondent clinically meaningful change in depressive symptoms from 2013/14 to 2015/16 was calculated by taking the difference in depression scores, regardless of what severity category they were in.

Table 1.7: Proportions of meaningful change on past two-week depression from 2013/14 to 2015/16

| Boys | Young men | Adults | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95%CI | % | 95%CI | % | 95%CI | |

| No change | 81.1 | [76.9, 84.7] | 72.7 | [66.3, 78.2] | 80.3 | [79.0, 81.6] |

| Clinically meaningful worsening | 8.4 | [6.0, 11.7] | 15.8 | [11.4, 21.5] | 9.3 | [8.4, 10.2] |

| Clinically meaningful improvement | 10.5 | [7.8, 13.8] | 11.5 | [8.0, 16.3] | 10.5 | [9.5, 11.5] |

| Total, % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||

| Total, n | 846 | 706 | 10,066 | |||

Notes: Clinically meaningful change was categorised as a change score on depressive severity of '5' points or more. CI = Confidence Interval.

Source: TTM data, Waves 1 and 2, all cohorts, weighted

The worsening of symptoms was greater among young men compared to boys and adult men. One in seven young men (15%) experienced clinically meaningful worsening over time, compared to a tenth of adults and boys (9% and 8%, respectively). Future research needs to explore these trajectories over a longer period to assess factors associated with worsening/improvement in symptoms.

One key symptom of depression is suicidality, which includes thoughts and behaviours around self-harm. Suicidality is more commonly experienced by those with severe depression (Li, Page, Martin, & Taylor, 2011), and can progress from thoughts about hurting or killing oneself to self-injury and attempting suicide. While most of those with depression do not experience suicidality, those who do often face great additional burden and risk to their lives. Given that a significant proportion of adults experienced severe depression, and 3% reported at least having thought about suicide in the past two weeks, it's important to explore past and recent suicidality among adult men, and how it may escalate over time. Therefore, suicidality, including thoughts and behaviours, is examined in greater depth.

Suicidality: prevalence, correlates and escalation

Suicide among men continues to be a paramount mental health issue. Recent statistics show that suicide continues to be more common among Australian men than women (AIHW, 2019a), with men making up more than three-quarters of suicidal deaths. On average, there are six male suicides every day. Research has also indicated that the rate of suicide increases over time (AIHW, 2019a; Conejero, Olié, Courtet, & Calati, 2018) for men, with the highest rate of suicide among those aged 30-59 years. In Australia, suicide results in the highest rate of years of potential life lost, with a total of 105,730 years lost every year.

To understand prevalence, patterns of change and escalation of suicidality over time, all TTM respondents were asked about their lifetime experience of suicidality at two time points, 2013/14 and 2015/16. In addition, adult males were asked about their experiences of suicidal thoughts and behaviours in the past 12 months in 2015/16 (Box 1.4).

Box 1.4: Suicidality

Suicidality (lifetime and in the past 12 months) was assessed using the following questions with binary response option (Yes/No):

- Ideation: Have you seriously thought about killing yourself?

- Plan: Have you made a plan about how you would kill yourself?

- Attempt: Have you tried to kill yourself?

These questions were asked of all TTM respondents 14 years old and older in 2015/16.

Note: Among all boys, only 14-year-old boys were asked questions about suicidality. Due to very small numbers, they were excluded from these analyses.

Prevalence of suicidality

Lifetime suicidal ideation was high, with around a fifth of young men and a quarter of adults reporting they had thought about hurting or killing themselves at some point in their lives (Table 1.8). Around a tenth of young men and adults had made a suicide plan in their lifetime.

Table 1.8: Suicidality among males across age groups in 2015/16

| Young men | Adults | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Lifetime | ||||

| Suicidal ideation | 21.1 | [16.4, 26.6] | 26.4 | [24.9, 27.9] |

| Plan | 13.5 | [9.7, 18.5] | 14.8 | [13.5, 15.9] |

| Suicide attempt | 6.8 | [4.3, 10.6] | 5.9 | [5.1, 6.7] |

| Total, n | 608 | 10,540 | ||

| 12-months | ||||

| Suicidal ideation | 9.5 | [6.3, 14.0] | 7.7 | [6.9, 8.6] |

| Plan | 6.0 | [3.7, 9.5] | 3.9 | [3.3, 4.5] |

| Suicide attempt | 2.3 | [1.0, 5.4] | 1.0 | [0.7, 1.4] |

| Total, n | 604 | 10,502 | ||

Source: TTM data, Wave 2, young men and adult cohorts, weighted

Between 5-7% of young men and adult men had made a suicide attempt in the past. Among adults, those suicide attempts ranged from very recent (the same year of survey completion) to up to 43 years ago, with an average time of 9.13 years since the last suicide attempt. Suicidal ideation in the past 12 months was elevated among young men, with about one-tenth reporting having thought about suicide.

Given a much bigger sample of adult men than young men, and therefore greater power to conduct further analyses, the following analyses focus on adult men only.

Socio-demographic correlates of suicidality

Risk factors associated with suicide are varied, and the strength of these associations vary across the lifespan (Fazel & Runeson, 2020). Some of the most robust risk factors include low socio-economic status and disadvantage (Pirkis et al., 2017), depressive symptoms (Li et al., 2011), unemployment (Blakely, Collings, & Atkinson, 2003), and identifying as non-heterosexual (Batejan, Jarvi, & Swenson, 2015; King et al., 2008). Previous findings using TTM data have shown that certain factors and experiences are associated with increased risk for suicidal ideation among men, including stressful life events and harmful alcohol use (Currier, Spittal, Patton, & Pirkis, 2016), job stress (Milner, Currier, LaMontagne, Spittal, & Pirkis, 2017), masculinity norms (Pirkis, Spittal, Keogh, Mousaferiadis, & Currier, 2016), and identifying as Indigenous Australian (Armstrong et al., 2017). Being able to identify those at risk of experiencing suicidality is an important step in preventing suicide in the community.

In the TTM sample, the socio-demographic characteristics associated with elevated risk for suicidal ideation for adult males were similar to those associated with depression (Table 1.9). Identifying as non-heterosexual was also associated with a significantly increased risk of suicidal ideation. Interestingly, among adult men, having a CALD background was associated with a reduced risk of suicidal ideation. Severe depressive symptoms were most strongly associated with suicidal ideation, above and beyond other socio-demographics.

Table 1.9: Socio-demographic factors associated with 12-month suicidal ideation among adult men in 2015/16

| aOR | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 | -0.01 |

| Non-heterosexuality | 1.48** | -0.23 |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | 0.88 | -0.26 |

| CALD background | 0.31*** | -0.09 |

| Highest level of education achieved (ref. = completed Year 12) | ||

| <Year 12 | 1.12 | -0.15 |

| Certificate/diploma | 0.95 | -0.12 |

| University degree | 1.25 | -0.31 |

| Employment status (ref. = employed) | ||

| Unemployed, looking for work | 1.01 | -0.16 |

| Out of labour force | 1.16 | -0.17 |

| Marital Status (ref. = single) | ||

| Widowed | 0.85 | -0.51 |

| Divorced | 0.81 | -0.20 |

| Separated but not divorced | 1.71** | -0.37 |

| Married/de facto | 0.90 | -0.11 |

| SEIFA (ref. = low disadvantage) | ||

| High disadvantage | 1.25* | -0.17 |

| Middle disadvantage | 1.32** | -0.16 |

| ASGS (ref. = inner city) | ||

| Inner regional areas | 1.05 | -0.11 |

| Outer regional areas | 0.97 | -0.12 |

| Remote/very remote | 1.33 | -0.92 |

| Depressive severity (ref. = none) | ||

| Mild | 5.93*** | -0.71 |

| Moderate | 16.42*** | -2.17 |

| Severe | 51.37*** | -7.31 |

| Total, n | 9,791 | |

Notes: *** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10. SEIFA = Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas; ASGS = Australian Statistical Geography Standard; CALD = Culturally and Linguistically Diverse. (ref.) is the reference category to which the other categories are compared. aOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio. SE = Standard Error.

Source: TTM data, Wave 2, adult cohort

Overlap of suicidal thoughts and behaviours

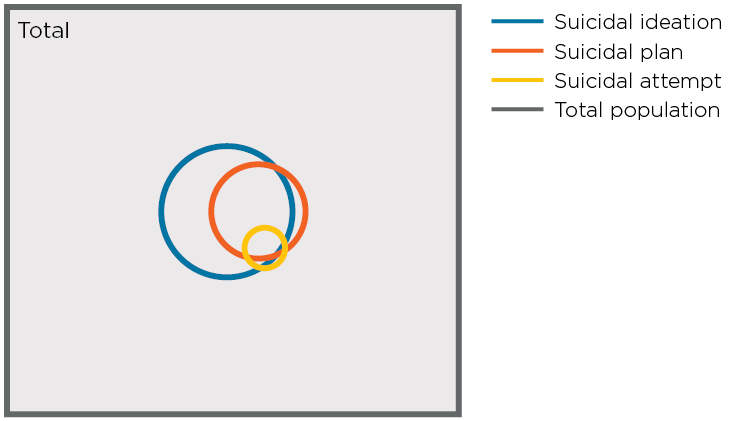

Most who think about suicide at some point in their life do not actually attempt suicide, and not all who attempt suicide display preceding ideation or planning. While it's well-established that ideation, planning and self-harm are related, there is a lot of variation in individual experiences of these. One important consideration is how suicidal thoughts and behaviours can occur independently or together, and how to get a better understanding of how people move from thinking about suicide to suicidal behaviours. Ideation, planning and actual attempts do not follow a straight path of escalation, and can occur simultaneously, consecutively or in isolation. Given this, it is vital to leverage and maximise insights drawn from longitudinal data to investigate suicide among Australian males as an important first step towards understanding how and why Australian men escalate to attempting suicide.

Studying escalation to suicide over time is crucial for identifying those at risk, as well as identifying those who may continue to hurt themselves, and to inform early prevention/intervention efforts. In particular, there are certain patterns indicating increased risk, such as where an individual has previously attempted suicide and attempts again, sometimes multiple times. Having made a previous suicide attempt significantly increases the likelihood that another will be made, and the chances of dying by suicide increase with repeated attempts (Christiansen & Jensen, 2007; Owens, Horrocks, & House, 2002).

While the majority of those who made a suicide plan also reported suicidal ideation, about 13% of those who made a plan did so in the absence of ideation (Figure 1.3). Further, not all who made an attempt in the past 12 months had planned an attempt in that time frame; about 12% of those who made a suicide attempt did so without having made a plan. Most who attempted suicide also reported suicidal ideation (87%).

Figure 1.3: Overlap of suicidal thoughts and behaviours in the past 12 months among adult men in 2015/16

Note: N = 10,124

Source: TTM data, Wave 2, adult cohort, unweighted

Credit: Ten to Men 2020

Almost half of those who reported suicidal ideation also made a suicide plan, and just over one-tenth had attempted suicide (Table 1.10). Only in a few cases did adult men appear to have made a suicide attempt in the absence of ideation or a plan.

Table 1.10: Prevalence rates of suicidal behaviour among those who reported suicidal ideation and a suicide attempt in the past 12 months among adult men in 2015/16

| Adults | ||

|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | |

| Among those who reported suicidal ideation: | n = 776 | |

| Proportion who made a suicide plan | 44.0 | [37.7, 50.5] |

| Proportion who attempted suicide | 10.9 | [7.6, 15.4] |

| Among those who reported a suicide attempt: | n = 78 | |

| Proportion who made a suicide plan | 88.2 | [76.2, 94.5] |

Notes: Overlap of suicidal thoughts and behaviours among adult men. CI = Confidence Interval.

Source: TTM data, Wave 2, adult cohort, weighted

Given the clear overlap and relationship between ideation, planning and making an attempt, it is imperative to investigate how, and how many, men escalate from suicidal thought and plans to suicide over time. This is the first step to identifying for who and why this escalation occurs, allowing for early identification of high risk to target prevention and intervention.

Escalation over time

Between 2013/14 and 2015/16, a small proportion of men escalated to a first suicide attempt (Table 1.11). Specifically, 0.6% of those who in 2013/14 said they had never attempted suicide had made an attempt by 2015/16; the majority of these were young men of whom 2.7% had escalated from no previous attempt to having made at least one attempt by 2015/16 (Table 1.11). Among those who had reported suicidal ideation in 2013/14, but no previous attempt, 0.4% had escalated to making a first attempt by 2015/16; this constituted 1.8% of all young men and 0.3% of all adult men.

Table 1.11: Escalation to suicide attempt by age group from 2013/14 to 2015/16 among Australian males aged over 15

| Young men | Adults | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Escalation from no previous attempt to a first attempt | 2.7 | [1.0, 5.9] | 0.4 | [0.3, 0.7] |

| Escalation from previous ideation to first attempt | 1.8 | [0.6, 4.2] | 0.3 | [0.1, 0.5] |

| Repeat attempters | 0.2 | [0.1, 0.9] | 0.5 | [0.3, 0.9] |

| Total, n | 694 | 9,821 | ||

Notes: Escalation was calculated using lifetime suicide data at Wave 1 and 12-month suicide data at Wave 2. Repeat attempts were those who had reported at least one suicide attempt in their lifetime at Wave 1 and had made at least one suicide attempt in the past year at Wave 2.

Source: TTM data, Waves 1 and 2, young men and adult cohort, weighted

Among those who made at least one lifetime attempt in 2013/14, there was a small group of repeat attempers who reported at least one attempt in the past 12 months in 2015/16. Around 0.5% of adult men had made at least two suicide attempts in their life. At a population level, this translates to over 26,000 adult men in Australia who are making repeated suicide attempts (not including those who potentially dying by suicide).

These findings highlight that while early suicidal ideation is associated with a greater likelihood of escalating to an attempt over time, there is still a significant amount of variation that suicidal ideation alone does not account for. However, given that the number of those who escalated to a suicide attempt was very small, it was not possible to conduct more in-depth analyses of risk factors associated with escalation.

Loneliness and mental health

Humans thrive on social connection; they feel and do better when they feel supported and part of a group. Loneliness involves experiencing distress or being upset because of feeling separated from others (AIHW, 2019b; Australian Psychological Society, 2018). It can be seen as a feeling of involuntary social isolation, and people can feel lonely even if surrounded by others. In Australia, one in four adults reported being lonely, and those who felt lonely had significantly worse physical and mental health (AIHW, 2019b). Loneliness and social disconnection are becoming a major mental and public health crisis as more and more Australians feel lonely (Relationships Australia, 2018). Men appear to be particularly vulnerable to experiencing loneliness in their lifetime (Australian Psychological Society, 2018), and this can have a significant impact on their mental health.

Men who are socially well-connected tend to have better health outcomes and lower mortality (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010). Similarly, evidence suggests that married men have longer life expectancies and lower disease burden compared to unmarried men (Kaplan & Kronick, 2006; Rendall, Weden, Favreault, & Waldron, 2011), with various theories suggesting why this may be. For example, it may be that married men are actively encouraged by partners to engage with health care services (Norcross, Ramirez, & Palinkas, 1996; Schlichthorst, Sanci, Pirkis, Spittal, & Hocking, 2016), or that those who are unmarried are more likely to engage in risky or unhealthy behaviours that may lead to poorer health outcomes or even early death (Kaplan & Kronick, 2006).

However, very little research to date has explored how loneliness may affect mental health outcomes above and beyond many socio-demographics associated with poorer mental health. Therefore, loneliness as a risk factor for poor mental health (including depression, anxiety and suicidality) is examined in consideration of the well-established socio-demographic characteristics. Loneliness among adult males was assessed based on having close friendships, as well as social support in general (see Box 1.5).

Box 1.5: Loneliness and social support

All adult men were asked about close friendships and overall social support in 2015/16.

Loneliness was classified according to how many close friends a respondent reported having. The question was: 'About how many close friends and close relatives do you have (people you feel at ease with and can talk to about what is on your mind)?' and respondents could indicate any number. This was recoded as a binary variable: no close friend (0), or at least 1 close friend (>1).

Social support was assessed using the Emotional/Informational Support subscale from the Medical Outcomes Scale (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991). It includes eight items (listed below), each rated from 1 'none of the time' to 5 'all of the time'. Scores are transformed to be from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicate more/higher social support. Further, a categorical variable was created for each item to look at how many men experienced very low social support. Ratings '1' and '2' were recoded as 'low support', rating '3' was recoded as 'some support', while ratings '4' and '5' were recoded as 'high support'.

Four per cent of Australian men reported having no close friend, suggesting these men are lonely (Table 1.12). At the population level, this would indicate that, in 2015/16, over 200,000 Australian men felt they didn't have a single close friend.

Table 1.12: Loneliness among adult men in 2015/16

| Number of close friends | % | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| No close friend | 4.0 | [3.4, 4.6] |

| At least one close friend | 96.0 | [95.4, 96.6] |

| Total, n | 9,992 |

Source: TTM data, Wave 2, adult cohort, weighted

Average overall social support among men was moderately high; although between 10% and 20% seem to lack social support in some areas. This is comparable to previous findings that around 1 in 10 Australians report lacking social support (Relationships Australia, 2018). Around 5% indicated 'low support' on all items, suggesting a general lack of any support. Around a quarter reported that they never - or almost never - had someone to share private worries and fears with (Table 1.13).

Further, self-reported social support was significantly lower among lonely adults compared to not lonely adults (based on having no close friend). For example, while around 10% of not lonely men said they had none or very little support in terms of having someone they can count on to listen, 66% of lonely men indicated that they had very little support in that regard. Overall, social support was also significantly lower among lonely adults compared to not lonely adults, highlighting that not having a single close friend is strongly associated with not having someone to share thoughts and feelings with, get advice from others or feel understood.

Table 1.13: Social support and loneliness among adult men in 2015/16

| Social support and connectedness Emotional/Informational support | Lonely adults % 'Low support' | Not lonely adults % 'Low support' |

|---|---|---|

| Someone you can count on to listen to you when you need to talk | 65.7 | 9.6 |

| Someone to give you information to help you understand a situation | 67.9 | 10.0 |

| Someone to give you good advice about a crisis | 69.0 | 10.7 |

| Someone to confide in or talk to about yourself or your problems | 74.2 | 12.9 |

| Someone whose advice you really want | 74.3 | 14.8 |

| Someone to share your most private worries and fears with | 78.6 | 20.8 |

| Someone to turn to for suggestions about how to deal with a personal problem | 75.4 | 16.1 |

| Someone who understands your problems | 75.6 | 15.7 |

| Mean (SD) | 23.7 (25.2) | 71.4 (25.0) |

| Total, n | 398 | 9,478 |

Notes: Being lonely was determined using the indicator above of number of close friends. Medical Outcomes Scale - Emotional Support Subscale Total scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more social support. M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation.

Source: TTM data, Wave 2, adult cohort, weighted

Loneliness, indicated here by having no close friends, was explored as a risk factor for poor mental health above and beyond the established socio-demographics often associated with depression, anxiety and suicidality. Over and above all these socio-demographic factors, loneliness was significantly associated with depression, suicidal ideation and planning (Table 1.14).

Table 1.14: Loneliness as a risk factor for mental health outcomes among adult men in 2015/16

| Depression aOR (SE) | Suicidal ideation aOR (SE) | Suicidal planning aOR (SE) | Suicide attempt aOR (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | 1.40** | 1.97*** | 2.23*** | 1.40 |

| (0.21) | (0.32) | (0.43) | (0.50) | |

| Observations | 9,410 | 9,347 | 9,350 | 9,319 |

Notes: *** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10. aOR = adjusted Odds Ratio; SE = Standard Error. Loneliness as a risk factor was assessed at the same time point as the outcome. For these multivariate logistic regressions, loneliness was added as a risk factor to all previously assessed socio-demographic characteristics to determine its role over and above socio-demographics. For depression, loneliness was added as an additional risk factor above and beyond socio-demographics at Wave 2; which showed a consistent pattern with the socio-demographics assessed as risk factors for depression at Wave 1 presented earlier in the chapter.

Source: TTM data, Wave 2, adult cohort

Loneliness experienced at the same time point (2015/16) was a significant risk factor for suicidal ideation and suicidal planning but not for attempts. That means that men who reported being lonely were around twice as likely to have thought about suicide or made a suicide plan in the past year. The statistically non-significant finding for suicide attempts may be due to the relatively small number of cases that attempted suicide in the past 12 months, limiting the statistical power to conduct multivariate analysis.

Given the high prevalence of mental health concerns among men, and the finding that some are experiencing either chronic mental health problems or relapsing, it is also important to investigate if these men are engaging with the appropriate health care services.

Health care use among males with mental health concerns

To address mental health concerns and associated outcomes among this group, it is imperative that males with mental ill-health engage with appropriate health care services and providers. However, use of health care services for mental health is especially low among men (ABS, 2007; Pepin, Segal, & Coolidge, 2009). Research has shown that men often do not seek treatment or support for mental ill-health for a variety of reasons, including stigma, lack of mental health literacy, and feeling able to deal with it alone (Affleck, Carmichael, & Whitley, 2018). To improve understanding of enablers and barriers to professional support for males with mental ill-health, this section explores engagement with services among those aged 15-60 with high depressive and/or anxiety symptoms, or with any suicidality, in the past 12 months.

A key step is identifying who men primarily turn to for help with an emotional issue, as well as their patterns of engagement - or lack of engagement - with health care services - when they are experiencing poor mental health such as depression, anxiety and suicidality.

Help seeking for emotional problems

When dealing with a problem or an emotional challenge, help can be sought from sources ranging from friends and family to professional health care providers and services. Participants were asked to indicate how likely they would be to seek help for an emotional problem (Box 1.6).

Box 1.6: Help-seeking behaviour

Help-seeking behaviour was measured by the following question:

'If you were having a personal or emotional problem, how likely is it you would seek help from the following people?'

Using a scale of 1 to 7 where '1' is 'extremely unlikely', and '7' is 'extremely likely', all young men and adult men were asked to indicate how likely they would be to seek help from a range of sources (e.g. friend, partner, relative, etc.).

Responses were further categorised into three groups: '1' 'extremely unlikely or unlikely', '2' 'neither likely nor unlikely', and '3' 'extremely likely or likely' to seek help from that source.

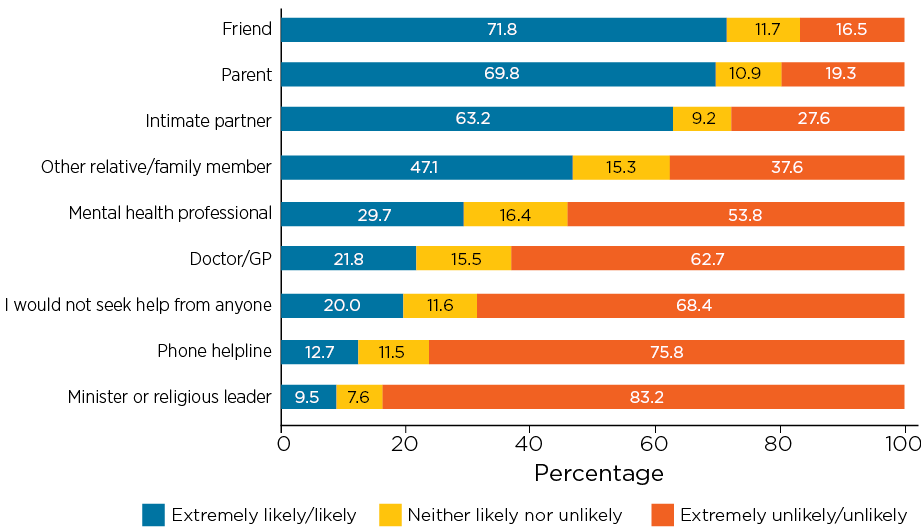

To seek help for emotional problems, both young and adult men (ages 15-60 years) said they would most likely go to a partner or friend, respectively. In contrast, the least likely sources of help for emotional problems were religious leaders and phone helplines. Just over one-fifth would not seek help from anyone.

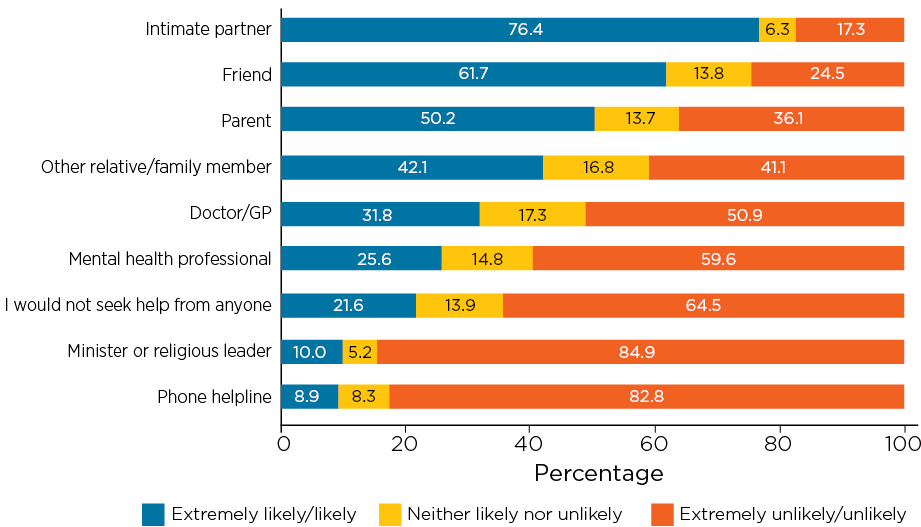

Over half of Australian males aged 15-60 years would be unlikely or very unlikely to seek help from a mental health professional in relation to an emotional problem (Figure 1.4), and even less would seek help from a phone helpline.

Figure 1.4: Percentage of adult men who said they would be likely or unlikely to seek support from these sources, 2015/16

Note: N > 10,253 for different items.

Source: TTM data, Wave 2, adult cohort, weighted

Credit: Ten to Men 2020

Adult men were somewhat more likely to say they would seek help from a doctor or GP, compared to young men; indeed, around one-third (32%) of men aged 18 years and over would seek help from a doctor or GP about emotional problems (Figure 1.4), compared to 22% of those aged 15-17 years (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5: Percentage of young men who said they would be likely or unlikely to seek support from these sources, 2015/16

Note: N > 594 for different items.

Source: TTM data, Wave 2, young men cohort, weighted

Credit: Ten to Men 2020

Those with a recent experience of mental health concerns (i.e. those with depression, anxiety or any suicidality in the past 12 months in 2015/16) were more likely to seek help from certain sources. Specifically, significantly more of those with depression indicated they would be likely or very likely to seek help from a mental health professional (47%) compared to those without depression (23%). The same was true for those with anxiety (51%) compared to those without (23%). However, there was no difference in how many with depression indicated they would be likely to seek help from a phone helpline (10%), compared to those without depression (9%). Again, the same was true for those with and without anxiety (11% vs 9%, respectively).

Contact with health care professionals among men with mental health problems

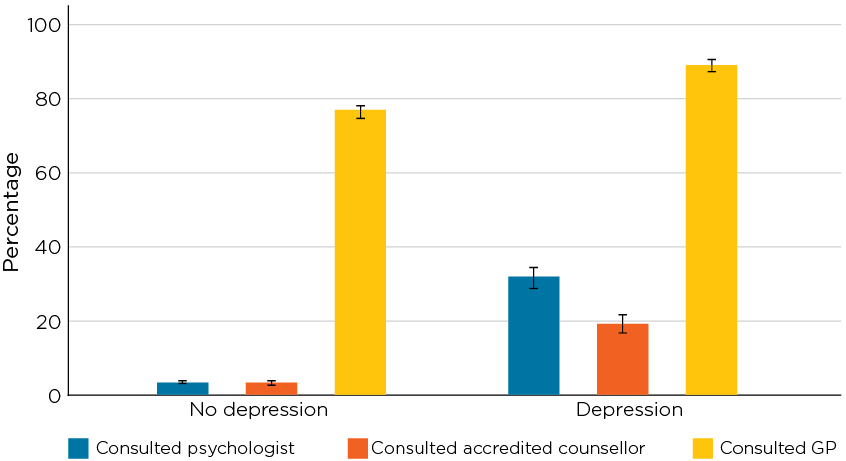

Men who experience mental health issues are more likely to have contact with some services compared to those without mental health issues.2 In 2015/16, although the majority of Australian males aged 18-60 had accessed a GP in the past year, more males with depression (89%) had visited a GP compared to those without (77%) (Figure 1.6). Adult men who had experienced depression in the past year were significantly more likely to have also seen a psychologist and accredited counsellor in the past 12 months than those without depression.

Figure 1.6: Health care use in the past 12 months by adult men with depression in 2015/16

Notes: N = 10,501. Brackets above/below bars represent 95% Confidence Intervals.

Source: TTM data, Wave 2, adult cohort, weighted

Credit: Ten to Men 2020

However, a significant proportion of men with mental health issues do not seem to be accessing professional support. Despite the higher uptake of mental health services among those with depression, only 40% of men with depression reported having seen a psychologist and/or counsellor.

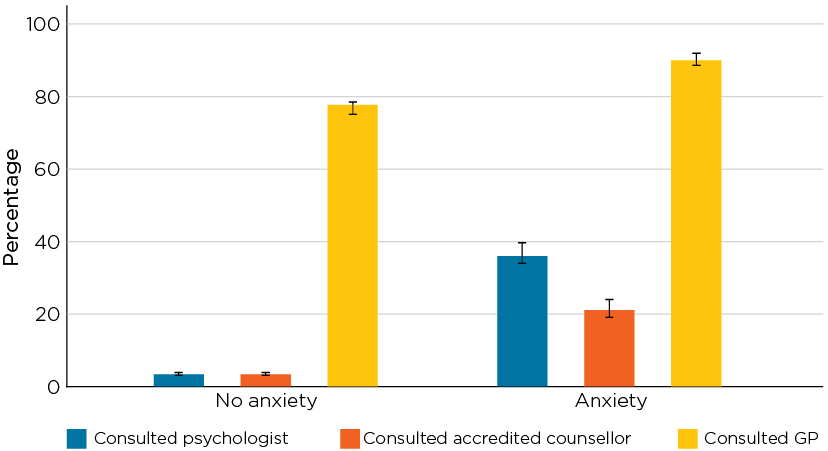

The same pattern emerged in relation to anxiety: adult men who had experienced anxiety in the past year were more likely to have seen a counsellor or psychologist during that time than those without anxiety (Figure 1.7). Among those with anxiety, less than 40% had engaged with a psychologist and less than 25% with a counsellor in the past year.

Figure 1.7: Health care use in the past 12 months by adult men with self-reported diagnoses of anxiety in 2015/16

Notes: N = 10,495. Brackets above/below bars represent 95% Confidence Intervals.

Source: TTM data, Wave 2, adult cohort, weighted

Credit: Ten to Men 2020

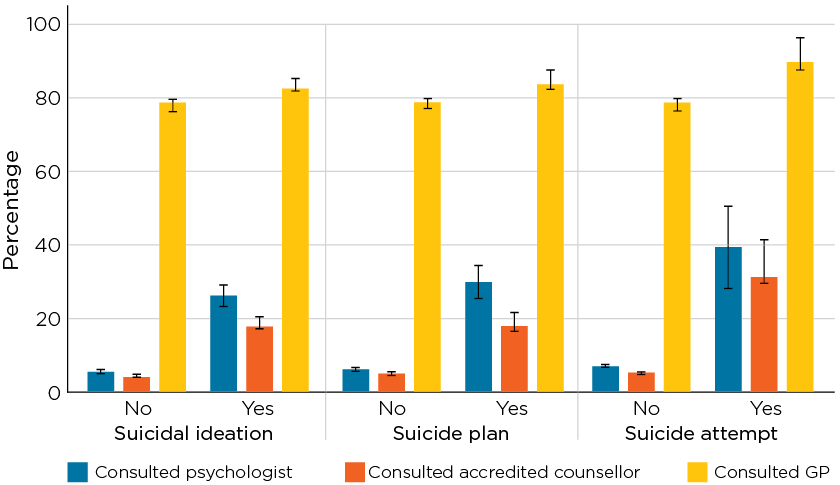

Health care engagement among adult men with any suicidality (thoughts and/or behaviours) was also explored. Similar patterns of health care use emerged for those with suicidality as with depression and anxiety (Figure 1.8).

While most adult men, regardless of suicidality, had engaged with a GP in the past year, there was significantly higher use of psychologists and counsellors among those who experienced suicidal ideation, suicidal planning or an actual attempt. However, only 40% of those who had made a suicide attempt in the past year had seen a psychologist during that time. Stated another way, over half of the men who had made a suicide attempt in the past year had not engaged with a mental health professional before or after the attempt.

Figure 1.8: Health care use among adult men by suicidality in the past 12 months in 2015/16

Notes: N = 10,479 for suicidal ideation, N = 10,489 for suicide plan, N = 10,506 for suicide attempt. GP = General Practitioner. Brackets above/below bars represent 95% Confidence Intervals.

Source: TTM data, Wave 2, adult cohort, weighted

Credit: Ten to Men 2020

2 Young men were only asked about a limited range of health care professionals they had contact with, and numbers were generally very small, and therefore not included in these analyses.

Conclusion

This chapter explored the significant burden of poor mental health among men and the gaps in men's help-seeking behaviour.

Poor mental health remains a significant public health concern among males. Up to a quarter of males experience diagnosable poor mental health in their lifetime, the most common of which is depression (20% of adult men). At any given point, around 15% of men of all ages reported experiencing symptoms or being treated for a mental health disorder in the past 12 months. Boys were more likely to have experienced anxiety (6%) than depression (4%), while young men and adult men were more likely to have experienced depression (7% and 12%, respectively) than anxiety (6% and 8%, respectively).

Experiences of poor mental health also appeared to be persistent over time. Over one-third of those adult males who experienced severe depression in 2013/14 were still experiencing this in 2015/16. This suggests that some men with severe depression are either not engaging with health care or mental health care services, the treatment they are receiving is not adequate, or they have had a relapse in that time (which is common (Hardeveld, Spijker, De Graaf, Nolen, & Beekman, 2010).

Suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts were reported by a notable proportion of men and appear to be more common among young men than older men. A small but significant group escalated or continued to make repeated suicide attempts within two years. This highlights the importance of understanding suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts, rather than only death by suicide, as previously identified in the priorities for suicide prevention and research (Reifels et al., 2017).

To inform where mental health promotion and suicide prevention efforts are needed as a matter of priority, it is important to identify men who may be at increased risk. Several socio-demographic factors were associated with poor mental health (depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation), such as higher area-level disadvantage, unemployment, being divorced or separated, identifying as non-heterosexual and/or identifying as Indigenous Australian. While several mechanisms are likely to play a role in these associations, there is a clear need to direct resources and support to those who may be experiencing several risks simultaneously.

The current suicide prevention research priorities include the need to develop and evaluate selective and indicated interventions3 for groups who may be at elevated risk of suicide (Reifels et al., 2017). Based on the findings of this chapter, suicide interventions are particularly needed for men living in disadvantaged areas, those who are experiencing a relationship breakup and separation (not divorce), and those displaying any degree of depressive symptoms.

Men experiencing loneliness were also at higher risk of developing poor mental health. While only 4% of men reported being lonely (not having a single close friend), the risk for depression, anxiety and suicidality among these men was almost doubled compared to those who had at least one close friend. As, in general, men are at increased risk of prolonged loneliness and find it difficult to talk about it with others (Franklin et al., 2018), it is imperative that loneliness among men is identified, de-stigmatised and mitigated through public health campaigns.

With appropriate care, mental health concerns are manageable and treatable through a range of psychological and pharmacological interventions, so accessing mental health care is an important step to getting better (Cuijpers & Dekker, 2005; Cuijpers et al., 2014). However, among men with diagnosable mental health concerns, less than half reported engaging with mental health care professionals. This highlights the extent of unmet needs and lack of engagement with the mental health care system among males.

Encouragingly, the majority of those with mental health problems (including a past year suicide attempt) reported seeing a GP in that time. This presents an opportunity for GPs to identify, treat or/and refer these men on to dedicated health care services and resources. Already, since the introduction of GP-specific mental health services billable under Medicare, this GP activity is increasing (AIHW, 2020). In addition to this initiative, public health campaigns that de-stigmatise mental health disorders, improve understanding of mental ill-health, and raise awareness about mental health care services and resources may encourage men to actively seek professional help sooner rather than later.

3 In the suicide prevention model, preventions are classified as universal, selective and indicated. Universal preventions can be applied to everyone, selective preventions to those may be experiencing some risk, and indicated to those who are at high risk (Life in Mind Australia, 2007).

References

- Affleck, W., Carmichael, V., & Whitley, R. (2018). Men's mental health: Social determinants and implications for services. Canadian Journal Of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie, 63(9), 581-589. doi:10.1177/0706743718762388

- Amato, P. (2014). Marriage, cohabitation and mental health. Family Matters, 96(5). Retrieved from aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/fm96-pa.pdf

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

- Armstrong, G., Pirkis, J., Arabena, K., Currier, D., Spittal, M. J., & Jorm, A. F. (2017). Suicidal behaviour in Indigenous compared to non-Indigenous males in urban and regional Australia: Prevalence data suggest disparities increase across age groups. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 51(12), 1240-1248. doi:10.1177/0004867417704059

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2007). National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of results. Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2019). ABS Causes of Death 2018. Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/Lookup/3303.0Main+Features12018?OpenDocument

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2016). Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2011. Canberra: AIHW.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2019a). Deaths in Australia: Leading causes of death. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from www.aihw.gov.au/reports/life-expectancy-death/deaths-in-australia/contents/leading-causes-of-death

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2019b). Social isolation and loneliness. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/social-isolation-and-loneliness

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020). Mental health services in Australia. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia

- Australian Psychological Society (APS). (2018). Australian loneliness report. Melbourne: APS. Retrieved from psychweek.org.au/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Psychology-Week-2018-Australian-Loneliness-Report.pdf

- Bailey, R. K., Mokonogho, J., & Kumar, A. (2019). Racial and ethnic differences in depression: Current perspectives. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 15, 603-609. doi:10.2147/NDT.S128584

- Batejan, K. L., Jarvi, S. M., & Swenson, L. P. (2015). Sexual orientation and non-suicidal self-injury: a meta-analytic review. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(2), 131-150. doi:10.1080/13811118.2014.957450

- Blakely, T. A., Collings, S. C. D., & Atkinson, J. (2003). Unemployment and suicide: Evidence for a causal association? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57(8), 594-600. doi:10.1136/jech.57.8.594

- Bulloch, A. G. M., Williams, J. V. A., Lavorato, D. H., & Patten, S. B. (2017). The depression and marital status relationship is modified by both age and gender. Journal of Affective Disorders, 223, 65-68.

- Christiansen, E., & Jensen, B. F. (2007). Risk of repetition of suicide attempt, suicide or all deaths after an episode of attempted suicide: A register-based survival analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 41(3), 257-265.

- Conejero, I., Olié, E., Courtet, P., & Calati, R. (2018). Suicide in older adults: Current perspectives. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 13, 691-699. doi:10.2147/CIA.S130670

- Cook, L. (2019). Mental health in Australia: A quick guide. Canberra: Parliament of Australia. Retrieved from www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1819/Quick_Guides/MentalHealth

- Cuijpers, P., & Dekker, J. (2005). [Psychological treatment of depression; a systematic review of meta-analyses]. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde, 149(34), 1892-1897.

- Cuijpers, P., Sijbrandij, M., Koole, S., Huibers, M., Berking, M., & Andersson, G. (2014). Psychological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 34. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2014.01.002

- Currier, D., Spittal, M. J., Patton, G., & Pirkis, J. (2016). Life stress and suicidal ideation in Australian men - cross-sectional analysis of the Australian longitudinal study on male health baseline data. BMC Public Health, 16(3), 1031. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3702-9

- Doran, C. M., & Kinchin, I. (2019). A review of the economic impact of mental illness. Australian Health Review, 43(1), 43-48.

- Dvir, Z. (2015). Difference, significant difference and clinically meaningful difference: The meaning of change in rehabilitation. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, 11(2), 67-73. doi:10.12965/jer.150199

- Evans, S., Banerjee, S., Leese, M., & Huxley, P. (2007). The impact of mental illness on quality of life: A comparison of severe mental illness, common mental disorder and healthy population samples. Quality of Life Research, 16(1), 17-29. doi:10.1007/s11136-006-9002-6

- Fazel, S., & Runeson, B. (2020). Suicide. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(3), 266-274. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1902944

- Franklin, A., Barbosa Neves, B., Hookway, N., Patulny, R., Tranter, B., & Jaworski, K. (2018). Towards an understanding of loneliness among Australian men: Gender cultures, embodied expression and the social bases of belonging. Journal of Sociology, 55(1), 124-143. doi:10.1177/1440783318777309

- Hardeveld, F., Spijker, J., De Graaf, R., Nolen, W. A., & Beekman, A. T. F. (2010). Prevalence and predictors of recurrence of major depressive disorder in the adult population. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 122(3), 184-191. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01519.x

- Hinz, A., Mehnert, A., Kocalevent, R.-D., Brähler, E., Forkmann, T., Singer, S., & Schulte, T. (2016). Assessment of depression severity with the PHQ-9 in cancer patients and in the general population. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 22. doi:10.1186/s12888-016-0728-6

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLOS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

- Kaplan, R. M., & Kronick, R. G. (2006). Marital status and longevity in the United States population. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(9), 760-765. doi:10.1136/jech.2005.037606

- Kessler, R. C., Amminger, G. P., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Lee, S., & Ustun, T. B. (2007). Age on onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychriatry, 20(4) 359-364.

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Walters, E. E., & Jin, R. (2005). Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6):593-602.

- King, M., Semlyen, J., Tai, S. S., Killaspy, H., Osborn, D., Popelyuk, D., & Nazareth, I. (2008). A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry, 8(1), 70. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-8-70

- Kocalevent, R.-D., Hinz, A., & Brähler, E. (2013). Standardization of the depression screener Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. General Hospital Psychiatry, 35(5), 551-555. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.04.006

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., & Lowe, B. (2010). The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: A systematic review. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4, 345.

- Krueger, R. F., Chentsova-Dutton, Y. E., Markon, K. E., Goldberg, D., & Ormel, J. (2003). A Cross-Cultural Study of the Structure of Comorbidity Among Common Psychopathological Syndromes in the General Health Care Setting. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(3), 437-447

- Li, Z., Page, A., Martin, G., & Taylor, R. (2011). Attributable risk of psychiatric and socio-economic factors for suicide from individual-level, population-based studies: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 72(4), 608-616. doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.008

- Life in Mind Australia. (2007). Living Is for Everyone: A Framework for Prevention of Suicide in Australia. Australia: Life in Mind Australia. Retrieved from lifeinmindaustralia.com.au/splash-page/docs/LIFE-framework-web.pdf

- Lorant, V., Deliège, D., Eaton, W., Robert, A., Philippot, P., & Ansseau, M. (2003). Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157(2), 98-112. doi:10.1093/aje/kwf182

- Milner, A., Currier, D., LaMontagne, A. D., Spittal, M. J., & Pirkis, J. (2017). Psychosocial job stressors and thoughts about suicide among males: A cross-sectional study from the first wave of the Ten to Men cohort. Public Health, 147, 72-76. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2017.02.003

- Norcross, W., Ramirez, C., & Palinkas, L. (1996). The influence of women on the health care-seeking behavior of men. The Journal of Family Practice, 43, 475-480.

- Owens, D., Horrocks, J., & House, A. (2002). Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 181(3), 193-199

- Pepin, R., Segal, D., & Coolidge, F. (2009). Intrinsic and extrinsic barriers to mental health care among community-dwelling younger and older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 13, 769-777. doi:10.1080/13607860902918231

- Pirkis, J., Currier, D., Butterworth, P., Milner, A., Kavanagh, A., Tibble, H. et al. (2017). Socio-economic position and suicidal ideation in men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(4). doi:10.3390/ijerph14040365

- Pirkis, J., Spittal, M. J., Keogh, L., Mousaferiadis, T., & Currier, D. (2016). Masculinity and suicidal thinking. Springer Heidelberg.

- Reifels, L., Ftanou, M., Krysinka, K., Machlin, A., Robinson, J., & Pirkis, J. (2017). Research priorities in suicide prevention. Melbourne: University of Melbourne. Retrieved from www.suicidepreventionaust.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Research-priorities-Report-FINAL_2017-11-03_0.pdf

- Relationships Australia. (2018). Is Australia experiencing an epidemic of loneliness? Findings from 16 waves of the Household Income and Labour Dynamics of Australia Survey. Canberra: Relationships Australia.

- Rendall, M., Weden, M., Favreault, M., & Waldron, H. (2011). The protective effect of marriage for survival: A review and update. Demography, 48(2), 481-506. doi:10.1007/s13524-011-0032-5

- Richards, D. (2011). Prevalence and clinical course of depression: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1117-1125. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.004

- Schlichthorst, M., Sanci, L. A., Pirkis, J., Spittal, M. J., & Hocking, J. S. (2016). Why do men go to the doctor? Socio-demographic and lifestyle factors associated with healthcare utilisation among a cohort of Australian men. BMC Public Health, 16(3), 1028. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3706-5

- Scott, R. L., Lasiuk, G., & Norris, C. (2016). The relationship between sexual orientation and depression in a national population sample. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23-24, 3522. doi:10.1111/jocn.13286

- Sherbourne, C. D., & Stewart, A. L. (1991). The Mos Social Support Survey. Social Science & Medicine, 32(6), 705-714. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B

- Williams, L. J., Jacka, F. N., Pasco, J. A., Coulson, C. E., Quirk, S. E., Stuart, A. L., & Berk, M. (2015). The prevalence and age of onset of psychiatric disorders in Australian men. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 50(7), 678-684. doi:10.1177/0004867415614105

Terhaag, S., Quinn, B., Swami, N., & Daraganova, G. (2020). Mental Health of Australian Males. In G. Daraganova & B. Quinn (Eds.), Insights #1: Findings from Ten to Men – The Australian Longitudinal Study on Male Health 2013-16. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.