Associations between vaping, mental health and risky health behaviours over time in Australian men

Ten to Men Snapshot Series – #1

May 2024

Key findings and implications

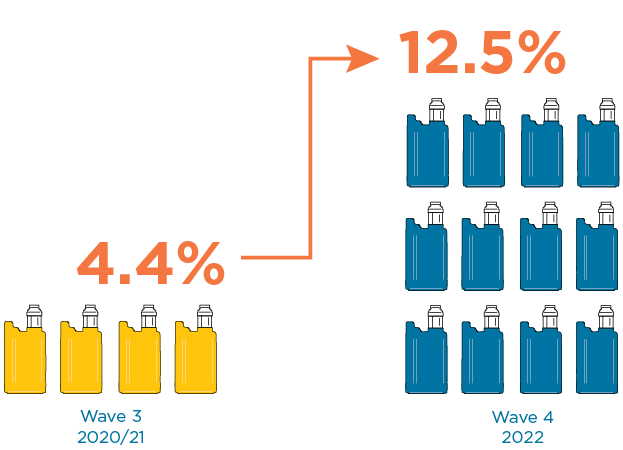

- The proportion of current vapers (men who vaped at time of survey) has tripled from 4% (approximately 260,000 men) in 2020–21 to 13% (approximately 760,000 men) in 2022. This highlights the need for ongoing efforts to decrease vaping among Australian men.

- Vaping increases as age decreases and is 10 times more common among males aged 18–24 years (30%) than males aged 55–65 years (3%). Strategies aimed at reducing vaping in the community should continue to focus on younger men.

- Rates of vaping are higher among men in major cities, LGBTQA+ people and men who feel lonely. Public health messages focusing on these population groups will help reduce vaping rates.

- Men who vape are 1.3 times more likely to engage in later illicit drug use and 1.6 times more likely to engage in later smoking.1 These findings demonstrate the potential dangers of vaping as a pathway to other risky health behaviours.

- Men who engage in risky behaviours (illicit drug use, heavy drinking, gambling at least weekly or smoking) are 1.8 to 2.7 times more likely to engage in later vaping.1 Interventions that successfully reduce these risky behaviours may also reduce vaping.

- Vaping does not appear to be associated with later mental ill-health (anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts and plans) in Australian adult males.1 However, further research, including over a longer time, is needed to establish whether this finding holds.

- Men with mental ill-health (moderate or severe depression, suicidal thoughts or suicidal plans) are 1.4 to 1.9 times more likely to engage in later vaping.1 Public health messages could focus on men with mental-ill health.

About Ten to Men

Ten to Men: The Australian Longitudinal Study on Male Health (TTM) is a nationwide longitudinal study on the health and wellbeing of Australian boys and men. TTM was established by the Australian Government’s National Male Health Policy (2010) and currently serves the National Men’s Health Strategy 2020–2030. This TTM snapshot is part of a series of research focused on preventive health commissioned by the Department of Health and Aged Care. More details on the TTM study can be found by visiting aifs.gov.au/tentomen.

What do we know?

E-cigarettes or ‘vapes’ were developed to help people quit tobacco smoking (Nayir et al., 2016) but have become a public health issue in their own right (Banks et al., 2022; Banks et al., 2023). There is limited evidence that nicotine e-cigarettes may be more effective than nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation (Banks et al., 2022). Further, vaping has many short-term health effects, including poisoning, toxicity from inhalation, lung injury, addiction, increased blood pressure and increased heart rate, and there is insufficient evidence to support the safety of long-term use of vapes (Banks et al., 2022; Banks et al., 2023).

Concerningly, the use of e-cigarettes has risen in recent years, particularly among people who have never smoked and those under the age of 35 years (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2024a; Scully et al., 2023; Wakefield et al., 2023). In fact, 78% of 14–17 year olds and 58% of 18–24 year olds in Australia had never smoked prior to trying vaping for the first time (AIHW, 2024a).

Vaping is also a significant public health concern due to its association with other risky health behaviours, including alcohol, tobacco and/or cannabis use, as recent national and international studies have reported (Chan et al., 2021; Leung et al., 2023; Pettigrew et al., 2023; Seidel et al., 2022). Moreover, people who have never smoked who use e-cigarettes are around 3 times more likely to take up smoking compared to people who have never smoked and have not used e-cigarettes (Baenziger et al., 2021).

Emerging evidence suggests that vaping is also linked with mental ill-health. One study found that vaping was associated with poor mental health in US adults (Cai & Bidulescu, 2024). Recent systematic reviews have found associations between vaping and mental ill-health (e.g. depression and suicidal ideation) among young people (Becker et al., 2021; Javed et al., 2022). Another study found a bidirectional association between depression and e-cigarette usage, that is depression was associated with later onset of e-cigarette use, while the sustained use of e-cigarettes over 12 months was also associated with increased depression over time in mid-adolescence (Lechner et al., 2017).

The available evidence shows that vaping is linked with other risky health behaviours and mental ill-health. However, the directionality of these associations is unclear.

How will this research build the evidence base?

There is limited research on vaping among adult men, including among specific groups. Most studies have specifically focused on adolescents and/or young adults. However, it remains important to conduct research with adult males, as current vaping rates have significantly increased among both young adult and middle-aged males in Australia in recent years (AIHW, 2024a). Ten to Men has information on vaping uptake to assess changing population burden in men, including across a range of socio-demographic characteristics.

Additionally, evidence on how vaping is linked to mental health and risky health behaviours is very limited, particularly in the Australian context. Most evidence is from cross-sectional research (e.g. Cai & Bidulescu, 2024; Leung et al., 2023), where information on vaping and mental health or risky health behaviours is collected at the same time (e.g. anxiety, depression or alcohol use is measured in the same survey as vaping). This prevents us from determining whether mental health and/or risky behaviours lead to vaping or vice versa. Understanding these associations is important given the rapid increase in vaping and the scarcity of research in this field. This paper uses longitudinal data from Ten to Men, enabling us to investigate the direction of associations between vaping and risky behaviours and vaping and mental health.

Finally, there is limited evidence on nicotine concentration in vapes and how this affects mental health. Many studies have not considered the concentration of nicotine used in vapes, which can vary widely (Kesimer, 2019). Nicotine is highly addictive (Mishra et al., 2015), and the relationship between smoking and poorer mental health is likely attributable to chronic nicotine use (Taylor et al., 2021). It can also affect brain development in adolescents and young adults (England et al., 2015). Therefore, the potential risks of vaping (e.g. poorer mental health) may increase alongside nicotine concentration. Ten to Men has unique longitudinal information on the concentration of nicotine used by men, allowing us to investigate how nicotine presence in vapes is associated with mental health.

After identifying the research gaps described above, we decided to address the following research questions:

- What are the prevalence and incidence of vaping among a representative cohort of adult Australian males? How does prevalence differ by age and priority population groups in the National Men’s Health Strategy (e.g. males living in rural and remote areas, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males, males from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds and LGBTQA+2 people)?

- What are the bidirectional associations of vaping with risky health behaviours (high alcohol consumption, tobacco use, illicit drug use and gambling)? That is, is vaping associated with later risky health behaviours and vice versa?

- What are the bidirectional associations of vaping with mental ill-health (anxiety, depression, suicidal thoughts and suicidal plans)? That is, is vaping associated with later mental ill-health and vice versa? How do these associations differ according to whether or not the e-cigarettes contain nicotine?

Data In Focus

Sample

This snapshot mostly uses data from Wave 3 (n = 7,919) and Wave 4 (n = 7,050) of Ten to Men, which were collected in 2020–21 and 2022, respectively (Wave 3 and 4, n = 6,322). Full details of the Ten to Men sample and study are available from: aifs.gov.au/tentomen.

Key variables

Key vaping measures were current vaping status (‘not a current user’ or ‘current user’) and nicotine presence (categories of: ‘do not vape’, ‘nicotine free’ or ‘nicotine present’ in e-cigarettes).

Risky health behaviours were illicit drug use in the past 4 weeks, gambling at least weekly, current smoking and alcohol consumption (with categories of ‘non-drinkers’, ‘up to 4 standard drinks’ and ‘5 or more standard drinks’ on a typical drinking occasion).

Measures of mental ill-health were mild or moderate/severe anxiety in the past 2 weeks (according to the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7 measure (Spitzer et al., 2006)), mild or moderate/severe depression in the past 2 weeks (according to the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001)), suicidal thoughts in the past 12 months, and suicidal plans in the past 12 months.

Key variables were available for both Waves 3 and 4. Further information on key variables and additional measures including covariates are provided in the supplementary materials.

Analysis

The prevalence of vaping and how this differed by age and priority population groups was reported using population-weighted statistics. The number of incident cases was reported as both an unweighted number and population-weighted estimate. We investigated the bidirectional associations of current vaping with risky health behaviours using unweighted multivariable multinomial logistic and Poisson regression analyses. We also investigated the bidirectional associations of (a) current vaping and (b) nicotine presence with mental ill-health using these regression analyses.

Prevalence and incidence of vaping among Australian men

The proportion of current vapers tripled between 2020–21 and 2022

In 2020–21, approximately 4% of males aged 16–63 years (or 260,000 Australian males) were current vapers (men who vaped at the time of the survey). By 2022, this proportion had increased to 13% of men aged 18–65 years (or 760,000 Australian men, Figure 1).

The increasing prevalence of vaping reported in Ten to Men is consistent with that reported in other recent Australian surveys such as the National Drug Strategy Household Survey (3% of adult males reported current vaping in 2019, compared to 8% in 2022–23 (AIHW, 2024a)). However, unlike Ten to Men, the National Drug Strategy Household Survey included people over the age of 65 years, which may partially explain the lower prevalence than in Ten to Men, given that vaping is more common among younger men (AIHW, 2024a).

In our study, of those who were current vapers in 2022, 40% reported vaping less than monthly and 41% reported vaping at least daily. Around 28% reported vaping more than 5 times a day. Full results are available in Table S2 of the supplementary materials.

Figure 1: Between 2020–21 and 2022, the prevalence of vaping tripled for Australian males Prevalence rates of current vaping in 2020–21 and 2022 in Ten to Men

The proportion of people who reported ever having vaped was around 1.5 times higher in 2022 than in 2020–21. Approximately 25% reported ever vaping in 2022, increasing from 17% in 2020–21. In 2022, 173 Ten to Men participants were new vapers – that is, they were not current vapers in 2020–21 and had not ever vaped prior to 2020–21. This increase is equivalent to approximately 230,000 men in the Australian population.

Full results of the population-weighted prevalence of current and ever vaping, and the frequency of vaping and nicotine concentration for males who were current vapers in 2020–21 and 2022 are available in Table S2 of the supplementary materials.

Vaping is more common among younger men

In 2020–21 and 2022, vaping rates were higher among younger men. In 2022, 30% of 18–24 year olds and 24% of 25–34 year olds were current vapers, compared to just 3% of men aged 45–65 years (Figure 2). Moreover, in 2022, around 1 in 2 men aged 18–24 years (49%) and around 2 in 5 men aged 25–34 years (42%) had ever vaped, compared to around 1 in 10 men aged 45–65 years (11%; Figure 2).

A similar pattern was observed for new vapers. Approximately 9% of 18–24 year olds and 6% of 25–34 year olds were new vapers in 2022, compared to only 1% of men aged 45–65 years. These patterns are consistent with recent Australian research, which has also found vaping more common with younger males than older males (AIHW, 2024a).

Figure 2: Vaping prevalence decreases as age increases for Australian men Prevalence rates of current vaping and ever vaping by age in 2022 in Ten to Men

Notes: Current vaping, N = 6,597, population estimate = 6,091,000; Ever vaping, N = 6,745, population estimate = 6,276,032.

Source: Ten to Men data, Wave 4, weighted

The prevalence of vaping is higher for men in major cities, LGBTQA+ people and men who feel lonely

We investigated how the prevalence of current vaping in 2022 differed between specific groups of men. The factors for which there were and weren’t differences between groups of men are listed below. Full results are available in Table S3 of the supplementary materials.

Table 1: Prevalence of current vaping in 2022 differed between specific groups of men

| Differences between groups of men | No differences between groups of men |

|---|---|

| Region. The prevalence of current vaping was 14% in major cities, 9% in inner regional areas and 8% in outer regional, remote or very remote areas | Indigenous status. |

| Sexuality and gender identity. The prevalence of current vaping was around 23% for LGBTQA+ people and 11% for heterosexual and maleidentifying people. | Socio-economic disadvantage. |

| Feeling lonely versus not feeling lonely. In 2022, 15% of those who felt lonely reported currently vaping, compared to 11% of those who did not feel lonely. | Disability status. |

Is vaping linked to other risky health behaviours for men?

Vaping is associated with later illicit drug use and smoking

Compared to males who did not vape, males who vaped in 2020–21 were 33% more likely to have used at least one type of illicit drug in the past 4 weeks and 59% more likely to be a current smoker in 2022 (Figure 3). These associations are consistent with those from international studies (Salmon et al., 2023; Silva et al., 2023). However, a distinguishing feature of our study is that it focused specifically on Australian men and considered a much larger range of ages, rather than just adolescents or young adults.

Current vaping in 2020–21 was not associated with risky drinking (5 or more standard drinks on a typical drinking occasion) or gambling at least weekly in 2022. This contrasts with previous international research, though there may be other reasons for this. A Canadian study by Salmon and colleagues (2023) found that vaping was associated with later alcohol consumption but that study only focused on adolescents and emerging adults. A US study by McGrath and colleagues (2018) found higher rates of vaping in gamblers than in the general population but that might be explained by the fact that some states in the USA exempt e-cigarettes from smoke-free legislation, allowing people to use e-cigarettes inside casinos.

Figure 3: Vaping is associated with a higher risk of later illicit drug use and cigarette smoking in Australian men Estimates of the association between vaping in 2020–21 and risky behaviours (illicit drug use in the past 4 weeks and current smoking, separately) in 2022

Notes: Full results are available in Table S4 of the supplementary materials. Covariates included are age, region, socio-economic disadvantage, Indigenous status, depression, anxiety, employment status, relationship status, education, culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) status, LGBTQA+ status and the relevant risky behaviour in Wave 3. Vaping was measured as current vaping status (‘not a current user’ or ‘current user’). Illicit drug use model, N = 4,774; current smoking model, N = 4,956.

Source: Ten to Men data, Waves 3 and 4, unweighted

Illicit drug use, smoking, risky drinking and gambling are associated with later vaping

People who engaged in risky behaviours (illicit drug use, gambling at least weekly, current smoking or heavy drinking) in 2020–21 were more likely to vape in 2022 (Figure 4).

- Men who used illicit drugs in the past 4 weeks in 2020–21 were 2.3 times more likely to be current vapers in 2022 (compared to men who didn’t use illicit drugs in the past 4 weeks in 2020–21).

- Men who gambled at least weekly in 2020–21 were twice as likely to be current vapers in 2022 (compared to men who didn’t gamble at least weekly in 2020–21).

- Men who were current smokers in 2020–21 were around 2.7 times more likely to be current vapers in 2022 (compared to men who didn’t smoke in 2020–21).

- Men who engaged in risky drinking (5 or more standard drinks on a typical drinking occasion) in 2020–21 were 1.8 times more likely to be current vapers in 2022 (compared to non-drinkers in 2020–21).

Engaging in light to moderate drinking (up to 4 standard drinks on a typical drinking occasion, compared to being a non-drinker) in 2020–21 was not associated with vaping in 2022 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Risky behaviours are associated with a higher risk of later vaping for Australian men Estimates of the associations between risky behaviours in 2020–21 (for each of illicit drug use in the past 4 weeks, gambling at least weekly, current smoking and alcohol consumption) and current vaping in 2022

Notes: Orange circles indicate risk ratios and vertical lines correspond to 95% confidence intervals. Risk ratios above the dotted (reference) line indicate an increased risk, below indicate reduced risk and across represent no risk. Full results are available in Table S5 of the supplementary materials. Covariates included are age, region, socio-economic disadvantage, Indigenous status, depression, anxiety, employment status, relationship status, education, CALD status, LGBTQA+ status and current vaping in Wave 3. Vaping was measured as current vaping status (‘not a current user’ or ‘current user’). Illicit drug use model, N = 4,808; gambling model, N = 4,866; current smoking model, N = 4,861; alcohol model, N = 4,859.

Source: Ten to Men data, Waves 3 and 4, unweighted

Is vaping associated with mental health for men?

Vaping is not associated with later mental health

Current vaping in 2020–21 was not associated with recent experiences of anxiety (mild or moderate/severe), depression (mild or moderate/severe) and/or suicidal thoughts or plans (past 12 months) for men in 2022. There were also no associations between specifically vaping nicotine-free or nicotine e-cigarettes in 2020–21 and anxiety, depression, suicidal thoughts or suicidal plans in 2022. Previous US research reveals a bidirectional association between vaping and depression (Lechner et al., 2017). However, this US study only considered adolescents. Full results are available in Tables S6 and S7 of the supplementary materials.

Poor mental health is associated with later vaping

Men with poor mental health in 2020–21 were more likely to vape in 2022 (Figure 5).

- Men with moderate or severe depression in the past 2 weeks in 2020–21 were 38% more likely to be current vapers in 2022 (compared to men without depression in 2020–21).

- Men who had suicidal thoughts in the past 12 months in 2020–21 were 90% more likely to be current vapers in 2022 (compared to men who did not have suicidal thoughts in the past 12 months in 2020–21).

- Men who made suicidal plans in the past 12 months in 2020–21 were 78% more likely to be current vapers in 2022 (compared to men who did not make suicidal plans in the past 12 months in 2020–21).

Mild anxiety and moderate/severe anxiety in the past 2 weeks in 2020/21 were not associated with current vaping in 2022. There was only weak evidence of an association between mild depression in the past 2 weeks in 2020/21 and current vaping in 2022.

Figure 5: Poor mental health is associated with a higher risk of later vaping for Australian men Estimates of the association between mental health measures (depression, suicidal thoughts and suicidal plans) in 2020/21 and current vaping in 2022

Notes: Full results are available in Table S8 of the supplementary materials. Covariates are age, current smoking, alcohol consumption, illicit drug use in the past 4 weeks, gambling at least weekly, socio-economic disadvantage, education, CALD status, Indigenous status, LGBTQA+ status, region, employment status, relationship status and current vaping in Wave 3. Vaping was measured as current vaping status (‘not a current user’ or ‘current user’). Depression model, N = 4,797; suicidal thoughts model, N = 4,506; suicidal plans model, N = 4,531.

Source: Ten to Men data, Waves 3 and 4, unweighted

There were some associations between mental ill-health and later vaping either nicotine or nicotine-free e-cigarettes. Men who had moderate/severe depression in the past 2 weeks in 2020–21 were around twice as likely as men without depression to vape e-cigarettes containing nicotine (compared to not vaping) in 2022. This finding is consistent with international research (Lechner et al., 2017).

Men who had suicidal thoughts in the past 12 months in 2020–21 were 2.7 times more likely to vape nicotine-free e-cigarettes (compared to not vaping) and 2.4 times more likely to vape e-cigarettes containing nicotine (compared to not vaping) in 2022.

There was either weak evidence of or no associations between anxiety or mild depression in 2020/21 and the likelihood of vaping either nicotine or nicotine-free e-cigarettes in 2022. Full results are available in Table S9 of the supplementary materials.

Implications for policy and practice

Ongoing efforts are needed to decrease vaping rates for Australian men

Rates of current vaping tripled from around 4% in 2020–21 to 13% in 2022. Since October 2021, Australians have required a prescription to legally obtain e-cigarettes with nicotine (Department of Health and Aged Care, 2024). However, Australian research from 2023 suggests that only 8% of vapers have a prescription (Llewellyn et al., 2023), meaning that most vapers appear to be purchasing nicotine-containing e-cigarettes illegally.

Vapes, most of which contain nicotine, are widely available at low prices from Australian tobacco and vape stores, grocery and convenience stores, liquor stores, non-food and food retail stores, cafés and petrol stations (Ritchie & Epstein, 2023). We found in Ten to Men, from August to December 2022, 77% of men who currently vaped reported using vapes containing nicotine.

Further regulations have been, or are being, introduced in 2024 regarding the import, availability, advertising and sale of e-cigarettes (Department of Health and Aged Care, 2024). Future research should investigate the impact of these regulations on vaping rates.

Strategies to reduce vaping should consider what is needed to achieve this for subgroups within the population

Vaping rates were disproportionately higher among specific population groups (younger men, men living in major cities and LGBTQA+ people). While interventions aimed at the general population are important, efforts should focus on reducing vaping among these groups with higher rates.

The higher prevalence of vaping in major cities may be due to ease of access to vapes (because of greater availability) in cities than in regional or remote areas. Greater enforcement against the illegal sale of vapes from retail and other settings may help to reduce access and therefore decrease vaping rates for men living in major cities. However, further research on the effectiveness of regulations over the long term is needed.

Globally, there is limited evidence available demonstrating the effectiveness of recent anti-vaping campaigns on specific population groups (Hair et al., 2023). A US campaign was associated with lower e-cigarette use and intentions to use e-cigarettes in young people (Hair et al., 2023) but research is needed on the effectiveness of such strategies in the Australian context.

Vaping is a gateway to other risky health behaviours

Men who vape are around 1.3 times more likely to engage in later illicit drug use and 1.6 times more likely to engage in later smoking. These findings demonstrate the harms of vaping as a pathway to other risky health behaviours. Tobacco smoking is the largest preventable cause of disease and death in Australia (AIHW, 2021). Additionally, illicit drugs present various harms to health (AIHW, 2024b). Therefore, it is important to reduce risk factors related to both smoking and illicit drug use.

Further research is needed on the directionality between vaping and mental health

We found that moderate/severe depression, suicidal thoughts and suicidal plans in 2020–21 were associated with vaping in 2022. However, vaping in 2020–21 was not associated with later mental ill-health in 2022. Given that the time gap between both waves of Ten to Men was quite short, it is too early to definitively conclude that vaping is not associated with later mental ill-health. Future research, with a longer time between when vaping and mental health are measured, is needed to further examine this relationship.

Next steps with Ten to Men data

Several related research questions could be investigated with current and future (e.g. Wave 5 in 2025) Ten to Men data.

Using current data:

- What are the bidirectional associations of vaping with physical health (e.g. asthma, sleep apnoea, infertility) and how do these differ according to nicotine presence and vaping frequency?

- How do associations of risky health behaviours with vaping differ according to nicotine presence and vaping frequency?

- How are specific types of illicit drug use and gambling (e.g. the most common ones) associated with vaping?

- What is the association between engaging in a specific number of risky health behaviours and vaping? For example, is risky drinking and smoking associated with a higher risk of vaping than smoking alone?

- Were the smokers who took up vaping largely dual users? Or had some quit smoking?

- Does vaping affect the risk of relapse (i.e. taking up smoking again) among men who have quit smoking?

Using Wave 5 (in 2025) data:

- What is the prevalence of vaping in Australian men in 2025 (after the introduction of further Australian government vaping regulations in 2024)? Has it changed compared to the prevalence in 2020–21 and 2022 and, if so, for which groups of men?

- What are the bidirectional associations of vaping with risky health behaviours and mental ill-health?

- How are groups or patterns of risky behaviours over time associated with later vaping in men? Are men who engage in risky behaviours over a longer period of time more likely to vape?

- Are men with mental health problems who use e-cigarettes to attempt to quit tobacco smoking more likely than those without mental health problems to use both e-cigarettes and tobacco over the long term?

- What are the associations of risky health behaviours and mental ill-health in 2020–21 with later sustained daily use of e-cigarettes in 2022 and 2025?

1In analyses investigating associations of vaping with risky health behaviours or mental ill-health, we adjusted for key variables (please see pp 6–8 below and supplementary material for further detail).

2No intersex (I) people were included in the Ten to Men sample. The ‘+’ symbol is used as some people responded ‘Other (specify)’, ‘Other identity (specify)’, ‘I use a different term’ or ‘I use a different term (please specify)’ to questions regarding sexuality and/or gender identity. A small number of people did not identify as male, which is why the term ‘LGBTQA+ people’ is used throughout this report.

Media releases

This snapshot benefited from academic contributions from Dr Elizabeth Greenhalgh and Dr Michelle Scollo at the Cancer Council Victoria, Dr Mandy Truong and Amanda Vittiglia at the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS).

The authors of this snapshot are grateful to the many individuals and organisations who contributed to its development and who continue to support and assist in all aspects of the Ten to Men study. The Department of Health and Aged Care commissioned and continues to fund Ten to Men. The study’s Scientific Advisory and Community Reference Groups provide indispensable guidance and expert input. The University of Melbourne coordinated Waves 1 and 2 of Ten to Men and Roy Morgan collected the data at both these time points. The Social Research Centre collected Wave 3 and Wave 4 data. A multitude of AIFS staff members collectively work towards the goal of producing high-quality publications of Ten to Men findings. Thanks are particularly extended to the survey methodology group (Karen Biddiscombe, Sarah Carr, Jennifer Renda, Kipling Walker, Jessie Dunstan, Ella Price) and the data management and linkage group (Melissa Suares, Frank Volpe, Leanne Howell) for their efforts in collecting and managing Ten to Men Wave 4 data. We would especially like to thank every Ten to Men participant who has devoted their time and energy to completing study surveys at each data collection wave.

Featured image: © GettyImages/zoranm