Do more Better Access sessions for men with depression or anxiety lead to improvements?

Ten to Men Snapshot Series – #2

June 2024

Katrina Scurrah, Monsurul Hoq, Anthony Jorm, Karlee O'Donnell, Constantine Gasser, Sean Martin

Downloads

Key findings and implications

- The target trial emulation using Ten to Men data showed no detectable effect of a higher number of Better Access treatment sessions from 2013–22 on improvements in depression symptoms in men.

- Results were similar for men in priority populations (including men living in rural and remote areas and men from CALD backgrounds) and also applied to anxiety symptoms.

- A higher number of Better Access treatment sessions during the COVID-19 period (2020–22) also did not appear to lead to improvements in depression symptoms during this period.

- Although this emulated trial found no evidence of causal effects of higher numbers of Better Access treatment sessions at a population level, there may still be important effects at an individual level.

- A key message for policy makers is that increasing the provision of mental health treatment alone may not be sufficient to reduce rates of mental ill-health among Australian men. Other factors (including treatment quality and out-of-pocket costs) require consideration to reduce the population level of mental ill-health.

- This target trial emulation study was limited by current dataset restrictions (including low numbers of participants classified as depressed and treatment sessions, other potential confounders not measured and limited service information).

- Ten to Men sample top-ups and future waves of data will address many of these study limitations, allowing for continued application of target trial emulation to evaluate policy related to men’s health.

About Ten to Men

Ten to Men: The Australian Longitudinal Study on Male Health (TTM) is a nationwide longitudinal study on the health and wellbeing of Australian boys and men. TTM was established by the Australian Government’s National Male Health Policy (2010) and currently serves the National Men’s Health Strategy 2020–2030. This TTM snapshot is part of a series of research focused on preventive health commissioned by the Department of Health and Aged Care (DOHAC). More details on the TTM study can be found by visiting aifs.gov.au/tentomen.

What do we know?

Mental health tops the list of the 5 priority health issues in the National Men’s Health Strategy 2020–2030 (NMHS). Further, all priority populations defined in the NMHS (including males living in rural and remote areas and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males) have higher risk of mental ill-health than the general population. The most common mental health issues for men are depression and anxiety (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2023). Both informal social supports and formal supports such as psychological treatment can affect treatment for and recovery from depression and anxiety (Lauzier-Jobin & Houle, 2022).

The Better Access to Psychiatrists, Psychologists and General Practitioners through the Medicare Benefits Schedule initiative (Better Access) provides Medicare rebates to eligible people (those with a diagnosed mental disorder) so that they can access the formal mental health support services they need (DOHAC, 2024).

Several earlier evaluations of the Better Access scheme have been completed (Jorm, 2018; Pirkis et al., 2011; Pirkis et al., 2022). The most recent, a comprehensive evaluation of the accessibility, responsiveness, appropriateness, effectiveness and sustainability of Better Access, was completed in 2022. This evaluation included 10 related substudies, one of which included data from the first 3 waves of Ten to Men as well as data from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH, Brown et al., 1998). The evaluation concluded that approximately half of participants who used Better Access services had better mental health at the end of the analysis period than at the beginning (Pirkis et al., 2022).

Randomised control trials (RCTs) represent the gold standard for assessing evidence for the effects of a range of interventions, such as a new medical treatment. Participants are assigned to either the control group or the intervention (new treatment) group randomly and this ensures that participants’ characteristics such as age and geographical location are balanced between the 2 groups. However, in many situations, such as Better Access-funded treatment sessions, it is not ethical or practical to randomise people in this way.

Recent methodological advances in the use of observational data to mimic this gold standard approach, known as Target Trial Emulation or TTE (Hernán et al., 2022), present opportunities to apply quasi-experimental approaches to provide high quality evidence of the causal effect of policies and policy changes. This new approach has begun to be applied to the development and evaluation of public policy using large, well-characterised, population-based cohort studies. Recent Australian examples include showing that household income supplements provided to lower income families may benefit children’s development and parental mental health (Goldfeld et al., 2024), and that a nurse home-visiting program for socially disadvantaged families is unlikely to be beneficial (Moreno-Betancur et al., 2023).

How will this research build the evidence base?

The 2022 evaluation could not conclude that use of Better Access services caused improvements in mental health. It found inconsistent evidence about whether more treatment sessions were associated with improved mental health. Due to the timing of the evaluation, follow-up after the COVID-19 period (2020–22) was not possible and Better Access policy changes implemented due to COVID-19 (such as an increased number of eligible sessions and increased use of telehealth services for delivery) could not be assessed.

Some initial studies published during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic reported that severity of depression was increasing during this period, especially for men (e.g. as discussed in Ellison et al., 2021). However, many of these estimates were derived from smaller, cross-sectional samples. Subsequent larger, cross-national systematic reviews suggested that minimal symptom changes for mental health were observed at the population level during the COVID-19 period (Sun et al., 2023). In any event, the effectiveness of the policy changes to Better Access services in response to COVID-19 has not been assessed.

The current research builds the evidence base on the effectiveness of the Better Access policy in addressing mental ill-health among Australian men before, during and after the COVID-19 period. Target trial emulation methodology is used to assess Better Access in a way that both builds on and is complementary to previous evaluations of the policy. Further, unlike past evaluations, in the current research the most recent wave of Ten to Men data (Wave 4, August–December 2022) was used, providing a longer assessment period and the ability to gain insight on Better Access policy changes in response to COVID-19. As far as we are aware, the TTE approach has not been widely used to assess the effects of health-related policies in Australia.

The following research questions were addressed by applying the TTE framework to longitudinal survey and linked data from Ten to Men:

- Does a higher number of Better Access treatment sessions lead to further improvements in mental health for adult men over the 10 years of Ten to Men?

- Does a higher number of Better Access treatment sessions lead to further improvements in mental health for specific priority groups in the National Men’s Health Strategy?

- Does greater use of Better Access treatment sessions during and immediately post COVID-19, between Wave 3 and Wave 4 of Ten to Men, affect depression and anxiety during this period?

Figure 1 describes and compares the ideal RCT approach to assessing evidence of treatment effects with the TTE approach applied here. Figure 2 summarises how the final sample size for this research was obtained from the full Ten to Men study sample.

Figure 1: A randomised controlled trial compared with a target trial emulation

Notes: This figure illustrates the differences between the ideal target trial and the emulation using Ten to Men data. Both the target trial and its emulation consider eligibility criteria, treatment strategies and other components. However, the emulation uses available data to mimic aspects of the target trial. A more detailed comparison is provided in the supplementary materials.

Figure 2: Target trial emulation showing cohort numbers and final sample size

Notes: This diagram illustrates how the final sample size was obtained for the main analysis, and at which stages men were excluded due to ineligibility. Only a small proportion of the sample recruited at Wave 1 both participated in Wave 4 and used any Better Access treatment sessions.

Data In Focus

Sample

Men who participated in Waves 1 and 4 of Ten to Men and consented to linkage, had mental ill-health at baseline and at least one recorded Better Access treatment session were included in analyses for research question (RQ) 1.1 For RQ2, men who were members of priority population groups in the National Men’s Health Strategy were included in the sample in addition to the previous criteria. For RQ3, men who participated in Waves 3 and 4 and consented to linkage, had mental ill-health at baseline and at least one recorded Better Access treatment session were included. Full details of the Ten to Men sample and study are available from aifs.gov.au/tentomen and full inclusion criteria are described in Table S1.

Key variables

Mental health pre and post Better Access treatment sessions was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9, Kroenke et al., 2001) for depression symptoms. Mental health need was defined as a PHQ-9 score greater than 5 and/or medication for mental health within 6 months of Wave 1 and/or self-reported treatment for depression in the last 12 months.

Anxiety symptoms were measured in Wave 3 and Wave 4 only using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006). Mental health need for analyses of anxiety was defined as a GAD-7 score greater than 5 and/or medication for mental health within 6 months of Wave 1 and/or self-reported treatment for anxiety in the last 12 months.

Better Access treatment sessions included specific Medicare item numbers (listed in Table S2 of the supplementary material) counted as either a total over calendar time (between Wave 1 and Wave 4) or per episode. An episode was defined as a series of Better Access treatment sessions for a man in which any 2 sessions were not separated by more than 6 months.

Analysis

Separate linear regression models were fitted to post-treatment PHQ-9 scores (RQ1–RQ3) and GAD-7 scores (RQ3 only). The main exposure was the number of Better Access treatment sessions attended (1–6 sessions vs >6 sessions), in total or per episode. The minimally adjusted analyses included only PHQ-9 and age (continuous). Adjustments were made in the main analyses for the additional confounding factors of region, culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) status, LGBTQA+2 status, Indigenous status, mental health medication use pre- and during treatment, stressful life events, education, household income and disability status (according to the definitions and causal diagram included in the supplementary material).

No evidence more Better Access sessions leads to improvement in depression symptoms

For RQ1, 490 eligible Ten to Men participants attended 5,925 Better Access treatment sessions between Wave 1 (2013–14) and Wave 4 (2022), with a median of 6 sessions. Half attended 4 to 16 sessions.

The categorisation of the number of sessions (1–6 vs >6) was selected in advance because individuals can attend up to 6 Better Access treatment series in a year under a single mental health care plan obtained from a GP without requiring a review or new referral. It was also expected to ensure approximately equal numbers in each of the 2 groups, and this was the case (1–6 sessions: 46.5%; >6 sessions: 53.5%).

As shown in Figure 3, depression symptoms at Wave 1 were lower for men who attended 1–6 sessions. However, the change in depression symptoms (as determined by the PHQ-9) was similar for both groups of men.

Figure 3: Change in depression symptoms was similar for low and high numbers of Better Access treatment sessions

Notes: Thin lines represent trajectories for the 490 individual men included in this analysis. The heavy lines represent the median values for men with 1–6 treatment sessions (in orange) and >6 treatment sessions (in blue).

For men of the same age and depression score at Wave 1, and after adjusting for key factors, there was no statistically significant difference in depression scores at Wave 4 for those with more (>6) or less (1–6) sessions (b = -0.19, 95% CI [-1.15, 0.70], p = 0.70).

In the previous evaluation of the Better Access treatment services, an effect size of at least 0.3 standard deviations of the baseline score of all participants who had used these services was considered a clinically relevant change, which corresponded to approximately a 1.5–2 unit change in the PHQ-9. On this basis, the difference of 0.19 units observed between the 2 Better Access treatment session groups (>6, vs 1–6) was not a clinically important difference (Copay et al., 2007).

The number of treatment sessions in an episode does not affect post-episode depression symptoms

An episode of Better Access treatment was defined as a series of Better Access treatment sessions in which any 2 consecutive sessions were less than 6 months apart. All episodes that were between the same 2 waves of Ten to Men were then combined into a single episode. More details about episodes are provided in the supplementary material.

In total, 835 eligible Ten to Men participants had 1,014 episodes and attended 9,632 Better Access treatment sessions between any 2 waves from Wave 1 (2013–14) to Wave 4 (2022). The median was 5 and 50% of men attended 2–9 sessions. Of these episodes, 25% included 1 or 2 sessions and 1% included 30 or more sessions. Most episodes occurred between Wave 2 and Wave 3 (Figure 3). Most episodes were shorter than the time between Wave 1 and Wave 4 (Figure 4, median 72 days) and included 1–6 sessions (64%).

The number of Better Access treatment sessions in an episode was not associated with post-treatment PHQ-9, indicating no difference in post-treatment depression symptoms. There was very little difference in post-treatment PHQ-9 between the 2 groups. The average PHQ-9 for men who attended more than 6 Better Access treatment sessions was 0.67 units higher than the average for men who attended 6 or fewer sessions, after adjusting for key variables. However, we are uncertain about the difference in average post-treatment PHQ-9 between the 2 groups as 95 times out of 100, this difference could be between -0.08 to 1.42, including 0, indicating no difference.

Table 1: Most episodes occurred between Wave 2 and Wave 3

| Wave prior to episode and wave post episode | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1 2 | 225 | 22.19 |

| 1 3 | 62 | 6.11 |

| 1 4 | 15 | 1.48 |

| 2 3 | 438 | 43.20 |

| 2 4 | 82 | 8.09 |

| 3 4 | 192 | 18.93 |

| Total | 1,014 | 100.00 |

Figure 4: Most men had fewer sessions in an episode and fewer days in an episode

Distribution of the number of Better Access treatment sessions per episode and length of episode (days)

Better Access treatment for men in priority populations does not affect depression

There were sufficiently large samples of some priority population groups to allow separate analyses:

- Men from CALD backgrounds (n = 180)

- Men younger than <35 years old (n = 195)

- Men living outside major cities (n = 178)

- Men without university education (n = 145)

- Men with household income < $100,000 pa (n = 294)

- Men with at least moderate depression at Wave 1 (n = 149).

However, there was no evidence of differences in depression symptoms at Wave 4 for those with a higher or lower number of sessions in any of the priority population groups, after adjustment for key variables including depression scores at Wave 1. The differences in average post-treatment PHQ-9 (which measures the depression symptoms) between those with a higher (>6) or lower (1–6) number of sessions were all small (Figure 5) and unlikely to be clinically relevant. Full results are included in the supplementary material.

There were only 65 eligible LGBTQ+ community members, 11 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and 56 men living with disability. Hence, we did not assess effects of Better Access treatment sessions on post-treatment PHQ-9 for these 3 priority population groups.

Figure 5: The number of Better Access sessions does not affect depression for members of priority population groups in the National Men’s Health Strategy

Notes: Squares represent estimates, lines represent confidence limits. The size of each square is proportional to the sample size for that analysis. Estimates are obtained from models that have been adjusted for PHQ-9 pre-treatment, age, Indigenous status, CALD status, LGBTQA+ status, region, income, education, employment status, SEIFA, medication for mental health during treatment, life events and other mental health supports used. The vertical line at 0 corresponds to no difference between PHQ-9 at Wave 4 for those who attended more than 6 treatment sessions, compared with those who attended 1–6 treatment sessions.

Additional Better Access treatment sessions during the COVID-19 pandemic did not improve depression in 2022 …

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of available Better Access sessions was increased from 10 per year to 20 per year (from 9 October 2020 until 31 December 2022) and telehealth access was also expanded from April 2020.

In total, 538 eligible Ten to Men participants with depression scores measured pre- and post-treatment attended 2,391 Better Access treatment sessions between Wave 3 (2020–21) and Wave 4 (2022). The median was 5 sessions and the interquartile range was 2 to 10, with both similar to the estimates for Wave 1 to Wave 4.

Men who attended more Better Access treatment sessions between Wave 3 and Wave 4 had slightly higher PHQ-9 scores (0.24 units higher, indicating worse depression) at Wave 4 than men who attended fewer treatment sessions, after adjustment for key variables. However, this difference is unlikely to represent a real or clinically important difference between the groups (95% CI [-1.37, 1.86], p = 0.77).

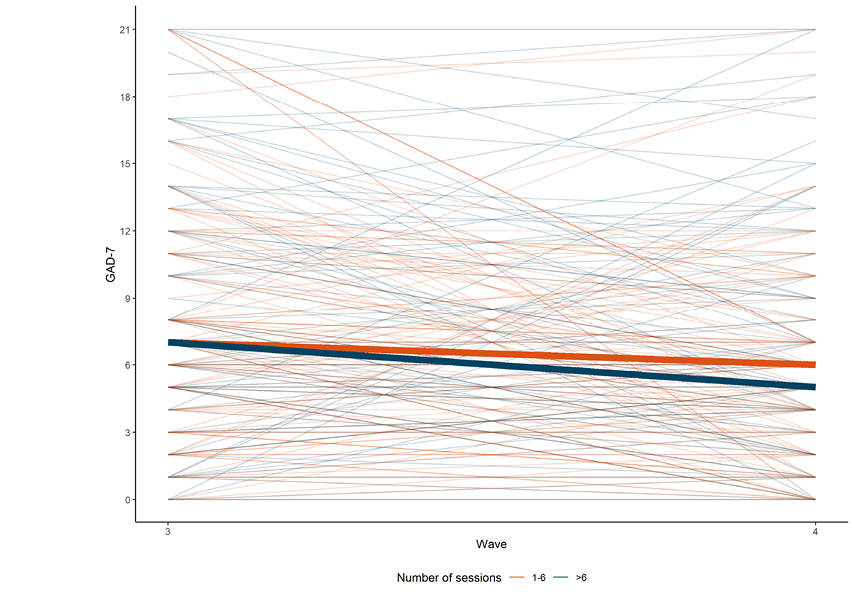

... with a similar result found for anxiety

When the analyses were repeated for anxiety symptoms, results were similar. In total, 500 eligible Ten to Men participants with GAD-7 measured pre- and post-treatment attended 2,391 Better Access treatment sessions between Wave 3 (2020–21) and Wave 4 (2022), with a median of 5 sessions.

Men who attended more Better Access treatment sessions (>6) between Wave 3 and Wave 4 had slightly worse anxiety at Wave 4 than men who attended 1–6 sessions. The estimated difference was 0.85 after adjustment for key variables (95% CI [-0.52, 2.22], p = 0.22).

Figure 7: COVID-19 results for anxiety show that change in anxiety symptoms was similar for low and high numbers of Better Access treatment sessions between Wave 3 and Wave 4, with substantial variation between men

GAD-7 scores at Wave 3 and Wave 4 for men who attended 1–6 treatment sessions or >6 treatment sessions between these 2 waves

Implications for policy and practice

Most men may not have received minimally adequate treatment

Both the quantity and quality of treatment for mental ill-health are important. Nearly half the men in our analysis (47%) received 1–6 Better Access treatment sessions between Wave 1 and Wave 4. Up to 6 sessions are available in a year under a single mental health care plan obtained from a GP without requiring a review or new referral, which is why we chose this categorisation.

However, the number of treatment sessions actually attended may not be sufficient to improve mental health. ‘Minimally sufficient treatment’ was defined as ‘taking an antidepressant or mood stabiliser for one month or longer, plus 4 or more consultations with any medical practitioner for mental health; or receiving CBT or psychotherapy, plus 6 or more consultations of 30 minutes or longer average duration with any health professional (except a complementary or alternative medicine therapist) for mental health.’ (Harris et al., 2015, quoted in Jorm, 2018). Less than 80% of men in our analysis attended 4 or more Better Access treatment sessions between Wave 1 and Wave 4, and less than two-thirds of men attended 4 or more sessions in an episode. It is likely that (using this definition) many did not receive a sufficient dose of treatment, although this cannot be confirmed using our data.

Men are less likely than women to seek help, especially for mental ill-health, and engage with health care services. Attendance at 1–6 sessions indicates that, in most cases, men have probably taken the step of seeing the GP and obtaining a mental health care plan and referral but chosen not to use the full 6 sessions (17% of men attended just 1 or 2 sessions). It is also possible that men chose to attend fewer sessions because they felt sufficiently recovered and did not need further sessions but our data are unable to capture this.

Little data were available to assess the quality of the treatment received, other than information about the type of provider. Most sessions were provided by either a clinical psychologist (40%) or a psychologist (53%). One in 5 men (20%) saw several different types of providers and men may have been treated by multiple different providers over time, which could reflect poor fit between therapist and client but could also be due to many unrelated factors. Therapist experience, strength of the therapeutic alliance, adherence to clinical practice guidelines and other factors likely to vary between sessions and practitioners were not recorded in Ten to Men.

Emerging evidence demonstrates that measuring such factors allows for identification of a ‘quality gap’, which may be equally as important as treatment gaps in reducing the population burden of common mental health disorders (Jorm, 2015). One of the qualitative studies included in the previous evaluation found that these treatment quality factors were important in helping participants engage with mental health professionals through Better Access.

Cost may also be a factor contributing to the lack of minimally adequate treatment, and was mentioned as a barrier in the previous evaluation. The average out-of-pocket cost for sessions between Wave 3 and Wave 4 was $51.14 (median = $57.55). However, the median out-of-pocket cost for sessions between Wave 3 and Wave 4 that incurred costs was $80.45, contrast to the median out-of-pocket cost3 of $63.90 between Wave 1 and Wave 2 and $69.70 between Wave 2 and Wave 3 reported previously (Pirkis et al., 2022). Around one-third of sessions incurred no out-of- pocket costs between Wave 2 and Wave 3 (Pirkis et al., 2022) and between Wave 3 and Wave 4.

Just over 1 in 5 men (22%) included in the current study reported a household income less than the 2013–14 median of $80,000 in Wave 1 (ABS, 2015) so cost is less likely to be a factor contributing to low usage in this analysis than in the population more generally.

Mental ill-health is complex and is affected by a combination of factors

Mental ill-health is complex and varies over time. We could not find evidence that more Better Access treatment sessions resulted in reduced depression or anxiety symptoms compared with fewer treatment sessions. The reasons for this finding are also likely to be complex.

Mental ill-health affects many areas of an individual’s life, such as employment and education (Productivity Commission, 2020), relationships (Li & Johnson, 2018) and family functioning (Sell et al., 2021). Similarly, an individual’s mental health is affected by many factors, at the individual, family and community level. Due to the broad range of intersecting factors that determine mental health (Affleck et al., 2018), it is likely that increasing the provision of mental health treatment alone may not be sufficient to reduce rates of mental ill-health among Australian men.

Existing evidence suggests that preventative efforts to address the determinants of mental ill-health such as unemployment, income, loneliness, community safety and discrimination are crucial to ensure the mental wellness of our population. These may need to be considered and addressed by multiple different government policies and entities working in concert with psychological services.

Target trial emulation is a useful approach to evaluating policies but requires large, well-characterised datasets with common health outcomes and treatments

This analysis has provided a trial of the TTE approach as well as an evaluation of the Better Access policy. We found that although Ten to Men is large overall, including over 15,000 men, with information on over 1,000 variables and linked data, this is still not large enough to provide evidence of any causal effects. The number of men with depression in Ten to Men was small relative to the ideal sample size required for this analysis and Better Access treatment was only used by about 10% of the sample.

Despite adjusting for key variables related to mental health, there are likely to be additional factors involved, which may have contributed to our lack of evidence of treatment effects. For example, information about the mental health need for which the treatment sessions were offered is not available in the linked MBS data. Although linked administrative databases are becoming increasingly valuable in health and policy-related research, they are not collected primarily for research purposes and cannot capture all, or even most, relevant information.

Observational longitudinal studies provide additional valuable insights as they include more comprehensive data on many relevant topics, such as help-seeking ideas, beliefs and behaviours, and validated symptom questionnaires such as the PHQ-9 and GAD-7, which provide a measure of symptom severity for all men, not just those with mental ill-health. They can also include measures that may be more sensitive to the nuances of male mental health.

Studies focused specifically on mental health, population-based studies that collect a wide range of individual-level data not available elsewhere, such as Ten to Men, and population-level data (such as linked MBS data for whole-population analyses), are complementary and all are required for a better understanding of population health monitoring and impacts, as discussed by Jorm (2018).

What else could we learn with Ten to Men data?

With current data:

- We could investigate the specific role of social inequality (e.g. income, education, region) on the number of Better Access sessions attended. Since mental health need should be the only factor that predicts usage, these demographic factors should not be associated with the number of sessions attended. A similar approach was applied by Parslow and Jorm (2000) to assess mental health service use.) This could provide additional information about the inequities described in the 2022 evaluation (Parslow & Jorm, 2000).

- We could investigate the effects of depression on functioning in daily life, and whether Better Access treatment sessions improve these difficulties. Although almost 500 men had mental ill-health at Wave 1, only 58 of these men reported difficulties with activities due to negative thoughts. Of these, over half (32 men) reported no difficulty with negative thoughts at Wave 4, and the median number of Better Access treatment sessions was higher for these men (22 sessions) than the men who did not improve (12 sessions). This is consistent with treatment affecting some symptoms of depression even if it does not affect all depression symptoms.

With top-up data:

- The measure of depression used in this study, PHQ-9, may not capture depression symptoms for men very well. Our top-up sample of over 10,000 men, which is expected to be completed soon, will be able to directly compare the PHQ-9 with an alternative measure, the short form Male Depression Risk Scale (MDRS, Herreen et al., 2022). These data will provide more information about how well or poorly PHQ-9 measures depression symptom severity for men and whether the MDRS is more useful.

With planned and future potential waves:

- As our top-up participants are incorporated into Wave 5 and beyond, most priority populations will be large enough to enable separate analyses. For example, over 1,000 additional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants have now been recruited and are expected to participate in Wave 5 in late 2024.

- We will also collect longitudinal data using a male-specific depression symptom questionnaire (the short-form MDRS) and be able to compare this with PHQ-9, in general, over time and for specific groups of men.

- Functioning in daily life may be influenced by symptoms of depression other than negative thoughts, such as difficulty concentrating or lack of motivation. Future waves will be able to assess the impact of depression on daily life activities using measures of functioning and symptoms in the MDRS.

1We chose to focus only on men who attended at least one Better Access treatment session because this group was more likely to be similar to each other than those not attending sessions. This similarity is important because it ensures the main difference between treatment groups is the number of sessions attended and the analysis is therefore closer to the target trial that is being emulated.

2No intersex (I) people were included in the Ten to Men sample. The ‘+’ symbol is used as some people responded ‘Other (specify)’, ‘Other identity (specify)’, ‘I use a different term’ or ‘I use a different term (please specify)’ to questions regarding sexuality and/or gender identity. A small number of people did not identify as male, which is why the term ‘LGBTQA+ people’ is used throughout this report.

3Converted to June 2022 dollars.

This snapshot benefited from academic contributions from Luke Gahan at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

The authors of this snapshot are grateful to the many individuals and organisations who contributed to its development and who continue to support and assist in all aspects of the Ten to Men study. The Department of Health and Aged Care commissioned and continues to fund Ten to Men. The study’s Scientific Advisory and Community Reference Groups provide indispensable guidance and expert input. The University of Melbourne coordinated Waves 1 and 2 of Ten to Men and Roy Morgan collected the data at both these time points. The Social Research Centre collected Wave 3 and Wave 4 data. A multitude of AIFS staff members collectively work towards the goal of producing high-quality publications of Ten to Men findings. Thanks are particularly extended to the survey methodology (Karen Biddiscombe, Sarah Carr, Jennifer Renda, Kipling Walker, Jessie Dunstan, Ella Price) and data management and linkage (Melissa Suares, Frank Volpe, Leanne Howell) groups for their efforts in collecting and managing Ten to Men Wave 4 data. We would especially like to thank every Ten to Men participant who has devoted their time and energy to completing study surveys at each data collection wave.

Featured image: © GettyImages/Ekaterina Fedulyeva